29 March 2015, Perth, Western Australia

Palm Sunday. On such a sacred day maybe it's worth us remembering a kind of odd question that Jesus once asked of his followers. 'If a child asks you for bread,' he said, 'will you give him a stone?' And on the face of it, a question like that's a bit of a no brainer, but it troubled his followers, I think. And it continues to trouble us now.

When children arrive on our shores, pleading for bread, for mercy, for safety, for refuge, do we give them what they desperately need or do we avert our gaze and turn them away and send them packing with nothing but a stone to weigh them down?

We're here, my friends, to call a spade a spade — to declare that what has become political common sense in Australia in the last 15 years is actually nonsense. And it's not just harmless nonsense. It's vicious, despicable nonsense. For something is festering in the heart of our community. Something shameful and rotten. It's born of a secret, I think. Something we don't like to acknowledge and something that we hide at terrible cost. You see, this is our secret. We're afraid. We're afraid of strangers. We're even scared of their traumatised children. Yes, this big, brash, rich nation, it trembles when people arrive with nothing but the sweat on their backs and a need, a crying need for safe refuge.

We're terrified. Especially if they arrive on a boat, we can no longer see victims of war and persecution as people like us. This fear has deranged us. It overturns all our moral standards, our pity, our tradition of decency, to the extent that we do everything in our power to deny these people their legal right to seek asylum. They're vilified as 'illegals', they're suffering is scoffed at or obscured, and our moral and legal obligations to help them are minimised or contested or traduced entirely.

Our leaders have taught us that we need to harden our hearts against these people. We can sleep at night, we tell ourselves, because these creatures, these objects are gone. We didn't just turn them away. We made them disappear. We weren't always this scared. We used to be better than this. And I remember this because I was a young man when this nation opened its arms, we opened our arms and our hearts to tens and thousands of fleeing Vietnamese. Back then we took pity on suffering humans. We had these people in our homes and our halls and our community centres. They became our neighbours, our schoolmates, our colleagues at work, and the calm, humane reception that we gave them reflected the decency of this country.

Now it's different. 15 years ago, our leaders began to pander to our fears. And now whether they like it or not, they are at the mercy of those fears.

In our own time, we have seen what is plainly wrong, what is demonstrably immoral, celebrated as not simply pragmatic, but right and fair. Both mainstream parties, as we've heard today, pursue asylum seeker policies based on cruelty and secrecy. A hardhearted response to the suffering of others is the 'common sense' of our day. But in the days of Charles Dickens, child labour was common sense. So was the routine degradation of impoverished women. The poor of Victorian England were human garbage, 'common sense' saw them exported offshore in chains to a gulag a long way out of sight. And these despised objects are our forebears. I have a forebear like that, my convict ancestor was a little boy. What's now known as an 'unaccompanied minor'. I've been thinking of him lately, and after reading of the degradation of defenceless women on Nauru and Manus island, I've been wondering how it could be that these things could happen in our time, on our watch, with our taxes, and in our name.

Until recently, we thought it was low and cowardly to avert our gaze from somebody who was in need. But that's where our tradition of mateship comes from, not from closing ranks against the outsider, but from lifting somebody else up, resisting the cowardly urge to walk on by. And when the first boat people arrived here in the seventies from Vietnam, we looked into their traumatised faces and we took pity.

Now we don't see faces at all. And that's no accident. The government hides them from us in case we should feel pity. Pity is no longer a virtue in this country. It's seen as a form of weakness. Asylum seekers are turned into cargo, contraband, criminals. And so, quite deliberately, the old common sense of human decency is supplanted by a new consensus — one that's built on suffering, maintained by secrecy, cordoned at every turn by institutional deception. This my friends is the new common sense.

But to live as hostages to our lowest fears, we surrender things that are sacred. Our human decency, our moral, right, our self respect, our inner peace. Jesus said, 'what shall it profit a man to gain the whole world only to lose his soul'. My friends, children have asked us for bread and we gave them stones.

Turn back my country, turn back while there's still time. Truly, we are still better than this.

Thank you

Recorded by Mark Tan and played on the ABC's Religion and Ethics report.

Daniel Webb: 'I can’t reconcile their compassionate words here at the UN and the cruelty that I’ve seen them inflict on Manus', outside United Nations Human Rights Council - 2018

2 March 2018, United Nations, New York, USA

We just delivered a big statement to the UN Human Rights Council about the 1800 innocent human beings who are still suffering on Manus and Nauru.

I think it’s probably the one thing that our Government doesn’t want to talk about here on the world stage. But it is so clearly the massive elephant in the room whenever they want to talk about human rights.

I mean, I’ve been to Manus myself three times, and I have seen firsthand the suffering.

I have seen the exhaustion, and the fear and the hopelessness on the faces of those men who have had five years of their lives ripped away from them in that place.

And then I come here, and I’ve heard our Government day after day talk about how important human rights are, and how all people are equal and deserve fairness and respect, and I’m sorry, but I just can’t reconcile the two.

I can’t reconcile their compassionate words here at the UN and the cruelty that I’ve seen them inflict on Manus.

And the fact that there are still one hundred and fifty children languishing in limbo on Nauru.

And I think there are governments here who just attack the very concept of universal human rights head on. But there’s also a really insidious threat that’s posed by governments like ours, who sit on the Council gnawing away at the very foundations of human rights with their own hollow words and unprincipled actions.

So we have, in the strongest terms, urged the UN and the international community to hold our government to account for its cruelty to refugees.

Daniel Webb: 'As we speak, there are 1800 innocent human beings including 150 children that the Australian Government has held in offshore camps for almost five years', UN Human Rights Council - 2018

2 March 2018, United Nations, New York, USA

Mr President,

In recent days this Council has sounded the alarm about chemical weapons attacks in Syria, the persecution of human rights defenders in Iran and the families being burned alive in their homes in Myanmar.

The Australian Government has professed its concerns, yet right now it is imprisoning people for fleeing these very atrocities.

Our Government will never want to talk about it here at this Council. But as we speak, there are 1800 innocent human beings including 150 children that the Australian Government has held in offshore camps for almost five years.

Time and time again this Council has warned our Government that its cruelty to refugees is unlawful and wrong.

And while our Government could give every single one of these people freedom and safety tomorrow, it is making the political decision not to.

Mr President, such deliberate and unprincipled cruelty by members of this Council gnaws away at the very foundations of universal human rights.

So, while the Australian Government will be hoping that this deep, dark stain on its human rights record is just ignored and forgotten, we urge this Council to ensure accountability.

Thank you.

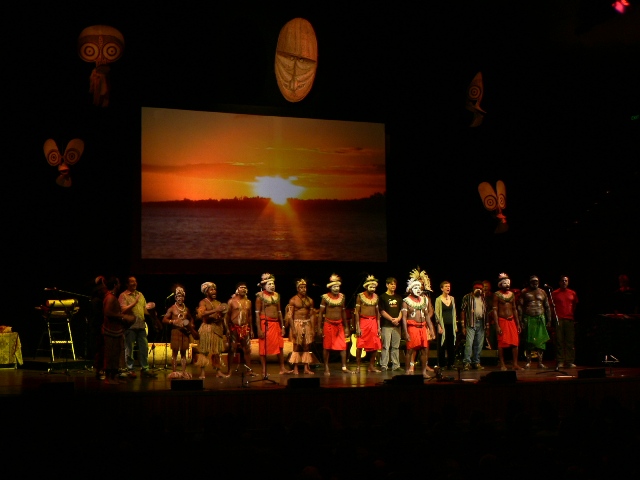

Photo David Bridie

David Bridie: 'For God's sake Australia, have a look at the map!', Lowy Institute Lecture on PNG - 2015

2 December 2014, Lowy Institute, Sydney, Australia

Australia is a better country when it engages with its immediate neighbours in Melanesia. We are vastly different, but we are neighbours. We should learn from each other, we should be fascinated with each other, we should engage, we should assist, we should respect, we should collaborate and we should definitely listen to each other. If we do so, we will both be better off. More to the point, to be situated so close to this Melanesian wonderland and to ignore it, is foolishness in the extreme.

Dip your toes into Melanesia and you will find evolving constitutions of emerging post-colonial states, an astounding array of species of flora and fauna (Google the way the Bird of Paradise turns itself inside out in its mating ritual), bright coloured coral fish that make a Leonid Afremov painting seem dull in comparison, active volcanoes, kustom, culture and conflict.

If you ever get the chance to look at an aerial photograph from Saibai Island in the Torres Strait over to the South coast of the Western Province of PNG, they are surprisingly close; it’s almost as if Australia is land locked. You could wade through this stretch of water at low tide.

My now departed good friend, filmmaker Mark Worth, once wrote a letter to The Australian newspaper venting his frustration at Australia’s lack of concern for Papua New Guinea and the troubles in West Papua with the short sentence, “For God’s sake Australia, just have a look at the map”.

As a young child in the outer suburbs of Melbourne I remember flicking through an Australian atlas my parents had that contained a section on PNG at the back. The accompanying pictures featured intriguingly strange and different flora and fauna. The orchids, birds and death adders fascinated and amazed my active child’s mind. It was a terrain so vastly different to our immense flat dry ancient continent.

Papua New Guinea should have been a source of massive fascination to Australia. One of only two former Australian colonies, the place of wartime and pre-colonial history, home to a quarter of the world’s languages, and some of the most culturally intact peoples on the planet. People still living on the same land, working the same gardens and singing the same songs as generations of their ancestors.

This is where it was all happening. But like our adherence to Hollywood, it was the USA’s backyard we fell for, not our own.

Our loss.

At the age of 21 I started a band called Not Drowning, Waving with a wonderful guitarist named Johnny Phillips. In the arty world of the inner suburbs Melbourne music scene we projected films on the wall behind the stage and our visuals guy was the aforementioned fella - Mark Worth, who was also a filmmaker in his own right.

Mark had spent the first 16 years of his life on Manus Island, now infamous as the site of the processing centre for our so called “illegal” asylum seekers. Mark’s father Geoff was in the navy at Lombrum near Lorengau.

Mark would regale us with stories of growing up in PNG as we sat up late drinking beer after our gigs on tour. He could talk under water, a maus wara as he would be called in PNG - an enthusiast. He said to me: “David, for your first trip overseas, don’t go to Europe, the UK or the USA. They are much the same as here. It’s an increasingly homogenous world. As a musician, as a person wanting to create and shift your thought patterns, you must go to PNG. PNG is a wonderland, it is life in the raw, and it is like going to another planet, it is, as they say, the Land of the Unexpected”

Hanging around the cultural sanctum of inner suburbs Melbourne in my university days, students and hipsters were more aware of the stories of America’s satellites such as Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala than we were of our own Melanesian neighbours. It wasn’t as if there was not much of interest going on there; civil wars in Timor Leste, West Papua and Bougainville and the newly independent Vanuatu.

Surely our engaged young minds should have been fixed on our close regional neighbours? But I knew bugger all. I would have thought any student with interest in the fields of history, science, geology, medicine, botany and especially religious studies would have found a wealth of intrigue in these countries.

Mark had by now started the Super 8 club in Melbourne and made a film called ‘Duwai bilong Ninigos’, about the canoe makers from the remote Western Islands of PNG who would collect large floating logs that had wound their way out from the Sepik river 200 miles to the south of their remote atoll – master craftsmen of the sea. Mark enticed me to compose the soundtrack to his humble short documentary. He played me recordings of pulsating Manus Island garamut drumming, joyous ukulele and 4-part harmony stringband music by the influential Paramena Strangers and the wall of sound that was Sanguma.

Sanguma incorporated traditional sing sing tumbuna music from a range of cultural groups all over PNG into their blend of funk and jazz. When they came and played a gig at The Venue, Melbourne’s principle rock venue, I was gob smacked as I witnessed pulsating garamut drumming, Sepik bamboo flutes, jews harps and cascading vocal chants - sounds I had never heard before. As a musical artist always in search of inspiration and something new, this was one of the greatest gigs I had ever witnessed.

As a result of this engagement from afar, the hooks of PNG had begun to sink into my consciousness.

Melanesian Adventure namba one

In 1986, I followed through on Worthy’s advice and booked myself on my first overseas trip to PNG. I managed to convince four other mates, two men and two women, to accompany me on a holiday that took in Moresby, the Sepik, Madang, Manus, New Ireland and Rabaul. It was to change my life.

Escaping the Melbourne winter - ples bilong ice box as singer George Telek would come to call it- we spent a whirlwind two days in the dry bustling capital of Port Moresby. We drank duty free gin with Henry - a young man we befriended at Jacksons Airport Customs - at 10pm on the foreshore Ela Beach, only to be told the following morning that under no circumstances should you ever go down to Ela beach after dark! Henry drove us around the settlements to visit his wantoks in the wee hours of the morning, my head spinning with the effects of the alcohol and the stunning excitement of being in a place where everything was new. I was gawking at every vista; my antenna was on full alert. It was only on further visits that it dawned on me that Moresby is a place where people come to find work and a party life, but often end up getting stuck there because it is expensive. And apart from the local Motuan people, these migrants of urbanisation don’t have land, contributing to the city’s edgy vibe.

Moresby was very different then from what it is now; an exciting burgeoning city whose time has arrived, with a growing middle class, a sense of confidence and pride and a beauty of its own, largely thanks to many of Powes Parkop’s urban policies of planting trees, placing artifacts in parks and roundabouts and keeping it clean.

From Moresby we travelled to the small bustling town of Wewak in the northwest. This was something different again. After an afternoon of body surfing out the front of the Windjammer Hotel with its puk puk bar, we headed down to the mighty Sepik River - one of the world’s great waterways. We definitely weren’t in Kansas anymore.

Sitting in the long dugout canoes as we headed up the tributary to Chambri Lakes, our guides were singing traditional melodies over the drone of the outboard motor. We passed heavily populated village after village, smoke from riverbank fires gently wafted into the air, sago and yam gardens were visible beneath tropically ascending cloud formations. The Sepik had a heat to it unlike anything I’ve experienced. The temptation to dive in and cool off was mighty, but as Jeff Buckley discovered much to his detriment, these big rivers have a forceful current that you don’t argue with. The current flowed strong and dragged with it large clumps of land that floated down the centre, carrying birds hitching a ride out to the coast.

The Sepik village culture and art is astonishing; the ornate Big Haus Tambarans, the carvings, the people, and the songs rich with story. Lying awake inside my mosquito net in the small haus kunai huts where we slept, I listened to the symphony of insect and bird noises and accompanying village sounds of dogs, chickens and tok ples chatter and tried to take in all that we had witnessed in the preceding few days. This wasn’t my world. This was something completely different. Village life has a thick humid grass-roots atmosphere and ambience to it that I still to this day find inspiring. It is life in the raw. What you see is what you get. It challenges your preconceptions and it can be confronting, with few of the comforts of suburban life. I was in a foreign wonderland.

Grassroots village life makes you see the world somewhat differently. You stop and let life wash over you. Life slows down, colours are intense, sounds reverberate. The western world could learn much from the way these societies treat their elderly (lapuns) with respect, value their knowledge, and look after them with their extended family system. Our technologically savvy children could do well to observe the way children in PNG villages contribute to the necessary responsibilities of gardening, sweeping and caring for the family, not to mention the physical activity of climbing kulau trees and diving for fish and lobster that is everyday life for PNG kids.

Like the art of the central desert of Australia, the Sepik take on carving and design is idiosyncratic and multi-layered. In all my travels since, I have rarely come across a place with such unique and inspired artistic and cultural practice. Chambri Lakes is the home of my great friend the master mambu (bamboo flute) player Pius Wasi. Pius formed a band called Tambaran Culture after leaving Sanguma where he had been a junior member of the band. Tambaran Culture became an integral part of the Not Drowning, Waving touring party and Pius has been a musical companion to me ever since. He is a man of genuine cultural knowledge and we have collaborated on film soundtracks, recordings, festival music and dance performances.

We boarded a trade boat to Madang, sailing past the symmetrically perfect volcanic island of Manam as the sun rose gently on the cool clear morning. Fat schools of tuna leaping out of the shimmering ocean, villages scattered along the distant shore, the gentle rock of the boat crammed amongst travellers with bilum bags full of kau kau and unfortunate chickens on their way to market.

Then it was on to Manus, the old Admiralty Islands. Through a family friend of Mark’s, Jim Paliau, we ventured by ocean-going outrigger to the small coral Ponam Island.

Manus is home to the unique garamut drumming, an intricate ensemble style of drumming where the syncopated rhythms are understood better as melodies and dance accompaniment, played on elaborately carved slit log drums of different sizes. In two years’ time Not Drowning, Waving would venture back to Ponam Island for two weeks of recordings with these master drummers.

From Manus we caught the short flight to bilas peles (beautiful place) Kavieng, the main town of New Ireland province. After a night in the old Kavieng Hotel, where I was confronted with a man stuck in the maddening midst of malarial fever, we caught a liberating ride on the back tray of a copra truck, wind in our hair as we belted down the Bulimiski Highway named after the grand poo bah of the German New Guinea rule pre-World War One. We stayed a night in a glorious cliff top colonial house with an old school plantation owner who was an example of the bad old days, with appalling attitudes to the locals and a revolver in his side pocket.

From Namatanai we caught a short flight into the jewel of the Pacific, Rabaul, the old capital of PNG up until World War Two that gets its name from the Kuanuan word for mangrove. The flight takes you through the volcanoes, circling the harbor onto the runway on the isthmus, an enchanting descent into one of the most picturesque places I have ever been.

Namba two ples bilong mi

Ah, Rabaul - this was the beginning of something special – musically and personally. That was my first visit – I have (so far) returned 35 times. It is my second home. Before the volcano destroyed the town in 1994, Rabaul was the jewel of the Pacific. Mango Avenue, Casuarina Avenue, Queen Emma’s steps, the tree lined streets, the market abundant in produce. Anything and everything grows in the rich soil of the Gazelle peninsula.

Catching a PMV bus in from near Kokopo to Rabaul town, I kept hearing this wonderful song “Abebe” by George Telek and the Moab Stringband. It was a bouncy stringband with a vocal to die for, about a butterfly spirit (Abebe means butterfly in the local tok ples, Kuanuan).

At this time, Rabaul had a thriving music industry - two 24 track-recording studios, Pacific Gold and CHM that ran 24 hours a day, seven days a week. There were gigs every night and Rabaul was home to two of the biggest PNG rock bands, Barike and Painim Wok (Telek’s rock band, doing a reformation tour in 2015), as well as a plethora of wondrous stringbands; Gilnata, Moab, Langa Vibrations, Revanmates and Junior Devils to name a few. Telek’s earlier stringband was The Junior Unbelievers Stringband, a great band name given the excessive missionary influence throughout the Pacific Islands.

Later that day I dropped into the Pacific Gold Studios, and serendipitously met George Telek and Glen Low. Later that evening we caught up again at a barbecue on Pila Pila beach, staring out to Watom Island. George, Glen and I drank SP, ate kakaruk (chicken) and talked about music. Both were huge Beatles and Credence fans, George still is, sadly my wantok Glen passed away from complications of Diabetes six years ago.

This was a fascinating conversation, three musicians from totally different worlds but our common link of music gave us a common language. Telek is the closest thing PNG has to a bona fide rock star. At the time Painim Wok cassettes were selling all around the country in massive numbers. The band’s co-founder John Warbat dressed in leather pants and jacket even during afternoon gigs with the temperature sitting at 33 degrees Celsius and 100% humidity, shredding away guitar hero style.

Little did George and I know that this barbecue on the beach would lead to us working together for the next 29 years, collaborating on the Not Drowning, Waving ‘Tabaran’ album, followed by me producing his five international solo albums plus one for the Moab Stringband, with an abundance of accompanying tours to all parts of Australia, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, the UK, USA and Europe. Telek would also collaborate with artists such as Archie Roach, Kev Carmody, Youssou N’Dour, Suzanne Vega, Bart Willoughby, Jimmy Little, Ngaiire and a host of others and garner an OBE for services to the PNG music industry. His anthem West Papua (Freedom) has such a following among West Papuans that it has become their defacto national anthem.

Not Drowning, Waving performing with George Telek, Photo: David Bridie

On my last night in Rabaul I spent the night in Raluana, Telek’s home village, and chilled down on the beach at Nrab point. Gazing out over Simpson Harbour, to the Beehives rock formation in the middle, to Nordup on the far side, to Tavurvur, the smallest of the volcanoes near Matupit - the one that would do the most damage in the 1994 eruption - I pondered how much history these people had witnessed over the last century and how much of this history Australia was a part of.

The 6-day war at Blanche Bay where the handsome Talili fought on behalf of his people in one of the first examples of organized native defence is a great feature film in the making. The life of the influential missionary George Brown, the Samoan Queen Emma and her commerce initiatives. A German colony under Albert Hahn up until 1918, the Germans had an organized tram system and set up very fruitful plantations and commercial enterprises.

From there the Tolais endured British and then Australian rule where the town of Rabaul was the capital, until we left it high and dry in the lead up to the Japanese invasion. The local Tolai people and many Australian nurses, civilians and soldiers were caught behind Japanese lines to fend for themselves. Also of note was the sinking of the POW ship the Montevideo Maru where over 400 Australian POWs and nurses were killed.

JK McCarthy’s biography ‘Patrol Into Yesterday: My New Guinea Years’ is a riveting read. One of the most positive accounts to come out of the Kiap and coast watcher era, McCarthy had the wisdom of Solomon about him and is perhaps the guiding example of what respectful engagement between our two countries should look like.

It is a cracking read.

Of equal fascination is the Matanguan Society’s role in agitating for indigenous rights in the lead up to independence, fortified by their Tumbuan society and secret belief system that has law and order, political and social objectives, represented in ritual form by the male Duk Duk and female Tubuan dances. Being secret, it was able to survive the vast changes brought about by missionary and colonial influences and remains strong and relevant today.

Leaving Rabaul we returned to Port Moresby, which was revealing having spent two months in the regions. Moresby made more sense now after being out in Sepik and the islands. We made a final visit to the museum, the Institute of PNG studies and the grand Parliament House; three important institutions that are still operating and are must-see places.

As we boarded the plane home at Jackson’s Airport, lining up with Australian mine workers straight out of their security compounds, my mind was filled to the brim with the exotic places and people of Papua New Guinea. Sounds and stories. Images and songs. Questions and enquiries. And many of these questions were not just about PNG but also about Australia-the way we live, the way we think, our approach to this wondrous world we find ourselves in. My world had been shaken up and stirred. My approach to music and sound would never be the same again.