5 November 2010, Glenaeon Steiner School, Middle Cove, Sydney, Australia

I am told to assure you that I eventually get around to the subject.

When I first went to East Lismore Primary School in 1947 there were still bomb shelters in backyards and a fear that a new big war with the Russians would soon break out. There were morning assemblies with oaths of loyalty to the King, rote-learning, rote-spelling, a national anthem, God Save the King, routine schoolyard bullying and a few sharp thwacks of the cane each month – on the hand, not the bottom – which we saw as a ritual of manhood in those days.

As was being in the cadets, playing war games away from home at age eleven, which I, from a pacifist religion, could not do. War was everywhere in our thoughts, and the atomic bomb, whose worst effects we were trained to evade by getting under the desk.

I felt, as a Seventh Day Adventist, an outsider. I could not play cricket on Saturday, nor go to the Saturday matinees at the cinema with my friends. I could not theoretically go to the movies either – there the Devil with heathen images tempted you to sin – though I did sneak out once a week with my mother’s connivance on my bicycle to see at the Star Court, Vogue and Vanity Theatre Alec Guinness movies, and The Ten Commandments and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, The Dam Busters and Reach for the Sky. We were God’s peculiar people, Pastor Breadon said and, boy, I felt that way pretty often, sneaking out of the cinema and wondering who had seen me go on.

I was saved, if that is the word I want, and civilised and made whole as a human being by the technological accident of radio which filled my mind with images and stories I cast myself in as they came by night into my crystal set, and a microgroove record of the Marlon Brando-James Mason Julius Caesar, which I can recite by heart, As Caesar loved me, I weep for him, As he was fortunate I rejoice at him, as he was valiant I honour him, and a teacher, Bill Maiden, whom I still see once a month at the Woy Woy fish restaurant to discuss the world’s news, and our long, long memories.

He taught me three times, for two weeks in 1951, for all of 1952, and in Modern History classes at Lismore High in 1957 and ’58. He made us sing, and write stories. He got the class of ’52 to write a novel, A Journey to the South Seas, in ten chapters, and read it out week after week to our peers. Mine concerned surviving dinosaurs on certain Pacific Islands, which Spielberg clearly stole from me forty years later, and the esteem which this gained for an otherwise tiny, bullied, frightened nerd, set me on the course which has made me a writer lifelong.

Bill believed in reading, and soon I was through David Copperfield, Kidnapped, White Fang, The Dam Busters, Boldness Be My Friend and The Sword and the Stone and, as it were, on my way down the road that goes ever on and on, the life of the mind that, through dreaming to order, nourishes our sympathy and takes us through lives not our own to the forks in the road of those lives and their beautiful and terrible destinations.

There were such teachers as Bill in those years, often men who had been in the war and in flapping tents in monsoon rains had read Thucydides in the original Greek and Orwell in orange Penguin paperbacks, but the culture did not favour them. The heroes of my day prevailed at rugby, and the swimming races, and the hundred yards sprints. It was the sissies like me who joined the drama groups, and the debating societies, and drew in charcoals and wrote satirical poems, and were more or less reviled for it.

I did not know that at that time the first Steiner Schools were beginning in this country and the kind of education I could barely imagine, powered by hundreds of teachers like Bill Maiden, was creeping into the leafier suburbs and stirring to magical thinking children my age.

But every now and then I glimpsed it. I had an eight millimetre projector, and some Chaplin films. I had a record of Orson Welles and Bing Crosby reading The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde, and a record of The Snow Goose, the fable of Dunkirk, starring Herbert Marshall as the hunchbacked hero in his little boat. My mother drove me to Mullumbimby one night to see Laurence Olivier in Hamlet and the Young Elizabethans came to town with Twelfth Night.

It was a near-run thing. A scholarship, narrowly discarded, bounced back to me, and I arrived a week late at Sydney University where Robert Hughes, Les Murray, Germaine Greer, Clive James, Bruce Beresford, John Bell, John Gaden, Richard Wherrett, Richard Butler, Richard Bradshaw, Richard Neville, Michael Kirby, Mary Gaudron, Graham Bond and Geoffrey Robertson, were all in attendance, and soon, in the drama societies and the newspapers and magazines, and the pub talk and the philosophic wrangle I entered the world I had nearly missed.

It always happens in clusters, I learned then, as Glenaeon proves every year.

To say a life of the mind is a good thing to embrace and a useful nourishment of your one life on earth is still not as universally accepted, now, I think, as it was for a while in the nineteen sixties and early seventies. Our current Prime Minister has never read an adult novel. The last American President did not read a book after university. Margaret Thatcher on achieving office had not been to a play at the National Theatre. All over our university system, cut courses in history studies, and music studies, and fine arts and art history, and Latin, and Greek and archaeology, and even Persian though it was Persian scholars who cracked the Ultra Code in World War 2 and won it, thinned the blood of our learning and drove good teachers, great teachers, into early drunken retirement in Queensland and unpleasant climaxes to once promising lives.

These are not small matters because, as all here well know, a young person whose life is deprived of art, and participative art, or music or word music, or dance or the explored past, may end badly, in drug-pushing, or stalking, or real estates, or worse. Adolf Hitler did not achieve the art scholarship he yearned for and would, I think, have been saved by, and found in World War I and its lessons a different course for his life, and sixty million others.

All teaching is the business of saving souls. But the business of Steiner is greater than that. It is the summoning to a soul of its better angels who uplift to a high plane of possibility that creative magic, that unstoppable glittering energy, that may change the world.

An extraordinary film now showing, The Social Network, the best film about American greed and American competitiveness and American hubris and American vengefulness since Wall Street, shows a life ill-chosen by a brilliant young man with Michelangelo possibilities who opted instead for the remorseless pursuit of billions through an adult toy of no great worth called Facebook, a sort of postcard brimming with trouble, when he might, had he been here, had he studied here, have been a painter, or puppeteer, a song writer, a set designer, a beloved friend of good friends instead.

I have two angelic children formed and shaped by the Steiner system and its celebration, its drawing out, its enhancement and congratulation of human possibilities. And I know how close each came to destruction before they arrived within its rooms and corridors of love. I know how much I owe, and I stand on the dock observing the voyage out of a future generation in a time more testing in its choices and its temptations than any before it, and I toast it, and I wish it bon voyage.

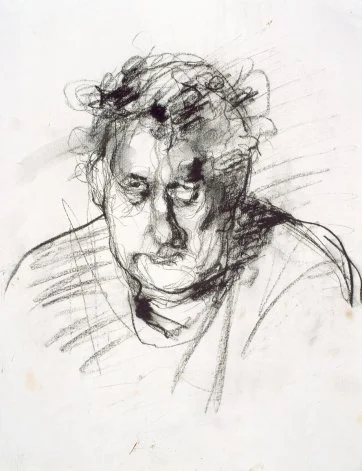

This exhibition is a measure of the great artistic diaspora of the children of Glenaeon whose homeward yearning far-off angel hearts remember from far Babylons of exile and longing how good it was, for a time, and what a time it was, it really was, in these hallowed rooms with these magic weapons of brush and charcoal, canvas, easel and sketch-pad, re-imagining the word.