19 Feburary 2017, Melbourne, Australia

Ginger Mick died 20 years before this commemoration, aged 80. This speech by his nephew was to celebrate the centenary of his birth.

Remembering Ginger Mick Rosemary and Jenny All the grandkids and great grand kids Members of the extended family Friends I pay my respect to the elders of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nations, the traditional custodians of this ancient land.

Twenty years ago, I had the honour of delivering the eulogy at Mick’s funeral, who was my father’s brother and so my uncle. I’ll begin my remarks this evening with the words with which I concluded that eulogy. Michael Lawrence Sheehan, born on the 1st of February 1917, was testament to the truth that ordinary people, through their actions and the values they both exhibit and transmit, achieve quite extraordinary things.

suppose this seems a bit trite these days, but like any adage or aphorism, depending on the person and the circumstances it references, it can either be true, sort of true or altogether untrue. Or It can be true for all the wrong reasons. I give you Donald Trump.

In Mick’s case, it was absolutely true. The sum total of Mick’s life was extraordinary – and in many aspects, bloody extraordinary. In your bus adventure today, you’ve already covered the formative years of Mick’s life – the Sheehan family moving from the far Wimmera town of Stawell, his school years, his love of athletics, the beginning of his engagement on social issues. So I’ll leave these things largely alone, although it’s necessary to reference these formative years to illuminate his mature years.

Undoubtedly, for anyone growing up in the 1930s and 1940s, both the Depression and the Second World War had an enormous impact on their lifelong outlook, their personal zeitgeist. We can reasonably suppose he forged his lifelong commitment to active engagement on social justice issues in this period, as evidenced by his joining the ALP. I have no evidence whatever of this but, him being an active practicing Catholic, you could reasonably suppose that his thinking and values were influenced by the Catholic Action movement and its various manifestations such as the Young Christian Workers (YCW) and the Catholic Worker group, with its focus on social justice and activism.

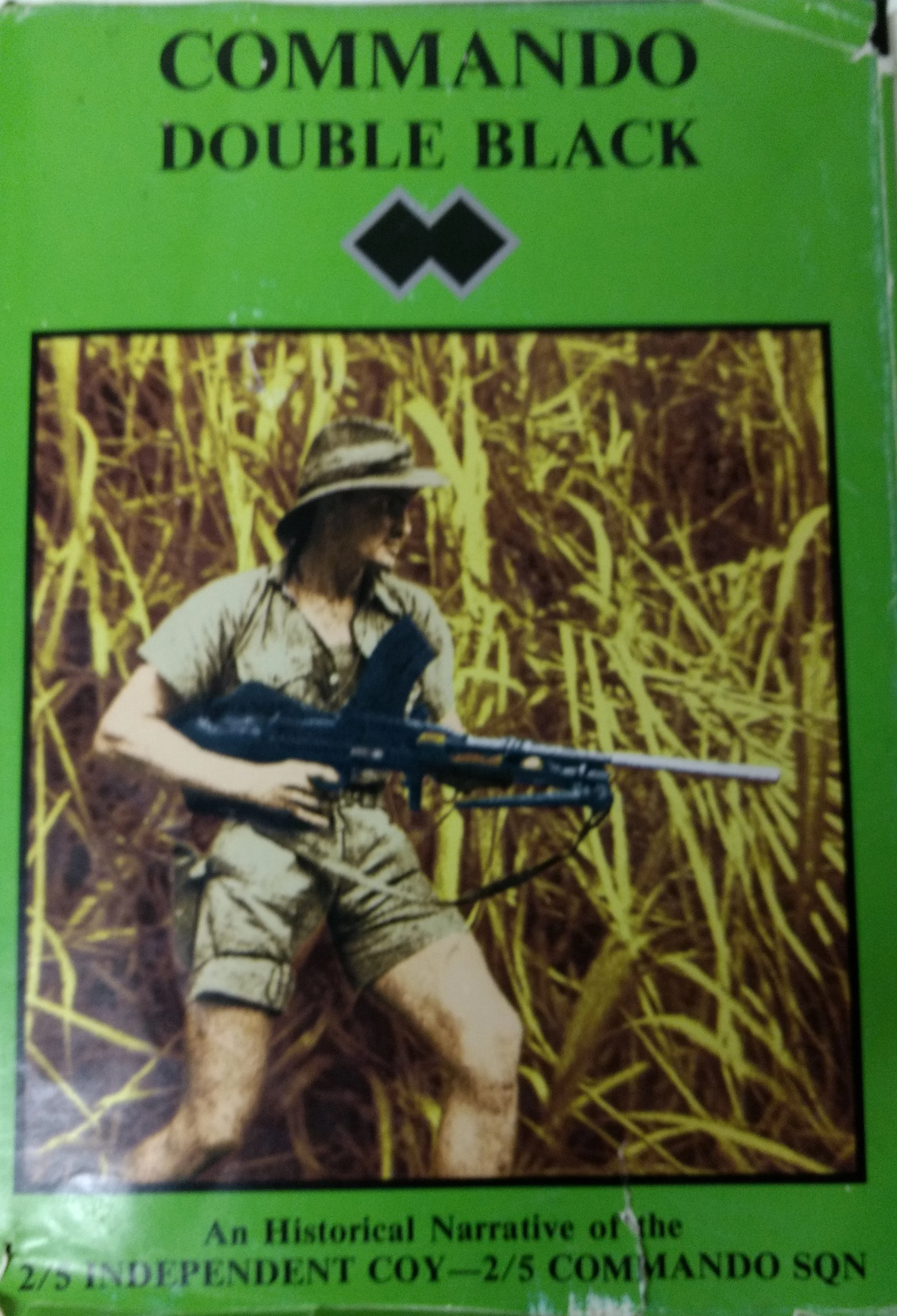

The outbreak of the Second World War brought activism of an entirely different kind. Mick enlisted in the Australian Army and went on to serve as a lieutenant in the 2/5 Independent Company (later 2/5 Commando Squadron) – the Commando Double Black – one of the forerunners to Australia’s Special Forces.

One of the first tests at Commando Training at Wilson's Promontory was for new arrivals to climb Mt Oberon (558 metres) in full battle kit. Those who failed to make it to the top and back in a certain time were returned to their previous units. Family lore has it that Mick had the record time for getting up and down. It’s never been quite clear to me whether that was for the whole war or for this particular training group but whatever, it was an impressive display of athleticism.

The role of the Double Black was not only to engage Japanese forces in conventional battle at the fore of Australian regular forces, although there was not a lot that was conventional about jungle warfare, but to also disrupt Japanese communications, conduct reconnaissance, keep the Japanese off balance. When deployed to New Guinea in April 1942, the Double Black, along with the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles, comprised Kanga Force, described as a ridiculous little army of at most 700 men, although at any one time only 450 were fit for battle.

Deployed in the area of Lae-Salamaua, they were faced by a Japanese force of 2200. But this ridiculous little army not only held the Japanese at bay until the battle hardened 7th Division could be redeployed from the Middle East, it was the only land force in the South West Pacific War Area that was taking offensive action against the Japanese for the first 9 months of the war. The exploits of the 2/5 are chronicled in this narrative history (Double Black – An Historical Naarative of the 2/5 Independent Company – 2/5 Commando Squadron) in which Mick had a part in producing, and to which daughter Jenny contributed the numerous maps.

I attended at least one get together of veterans of the company and I was struck by how seemingly insouciant they were about their experience. But you only have to casually flick through this volume to understand that there was nothing at all to be insouciant about: the constant rain – up to 300 inches a year in some places – and so the mud, the difficult terrain and the dense jungle, mosquitoes and malaria and of course, the constant threat of annihilation by a numerically superior enemy. And it’s not as if they were well supported in the material sense.

At one stage Mick was in command of a forward Observation Post and so in close proximity to enemy forces. There’s a series of communications to Mick, reproduced in this volume, from company headquarters full of apologies for essentials that couldn’t be supplied, such as iodine and boots. One begins: “Dear Mick, Well we have had a lot of bad luck with your rations. I won’t try and explain all the accidents now.” That must have made his day: rain, mud, mosquitoes, Japanese – and limited rations. My personal favorite is the one that said “Sorry can’t let you have some pig as intended. Pig died at Kaisnik. Next pig has not arrived.” It was around Christmas.

At one time Mick’s F Section (which became F Troop when attached to the 7th Division) was inserted into Japanese occupied territory to reconnoitre and maraud. After a week, they were picked up off a beach by a US Navy destroyer. After a week bashing around the jungle, you can imagined they were in a dishevelled state. Safely embarked, Mick was confronted by a USN officer who upbraided him, as the officer commanding the section, for their “disgraceful appearance and lack of military discipline. “Not only did they fail to salute, one of them told me to fuck off,” he said. The story goes that Mick pulled himself up to his full 5 foot 6 inches, saluted crisply and said loudly, as one does in the Army, “Sir, that would be a jolly good idea!” He then wheeled around and marched off, in best military fashion, to rejoin his men

The 2/5 went on to participate in the invasion Balikpapan in Borneo as part of the 7th Division. They witnessed the formal surrender of Japanese forces on Borneo as the war drew to a close. Mick recalled some years later: “And so it ended. Nobody said ‘Thank you’. We just went home.” Well, let’s give thanks now. Mick left an invaluable record of his part in the war. Against all regulations, he took to the war his cine film camera. If you Google AWM-Michael Sheehan you’ll find a 20 minute clip. Later on, he also donated his officer’s kit to the Australian War Memorial (AWM), where it forms a separate exhibitio

n. My son Gabe is an officer cadet at Duntroon and his platoon recently visited the Memorial and when they came to that exhibit someone asked the obvious question as to whether Gabe and Mick were related. When Gabe said Mick was his great uncle they all cheered.

So Mick came home from the war, home being in this case Melbourne, with the former Mary Lourey who he had married in May 1944. Prior to the war, Mick had been employed in various clerical positions before joining the public service in 1938 with the Department of Admin Services – a department I had an association with in the 1990s, but due to outsourcing it no longer exists. Mick was fond of telling me, and I suppose others, that capitalists and Tories strive to privatise surpluses and socialise losses, and it was never more true than in the case of so much government outsourcing, let me tell you.

After being de-mobbed in 1946, Mick rejoined the public service in what was then the Census and Stats Division of Treasury, and is now ABS. Mick also enrolled in a Bachelor of Commerce degree at The University of Melbourne, graduating in 1953. In contrast to today, where the public sector is by far the most unionised sector of the economy, the industrial organisation of public servants was very feeble in the 1950s, with some rather tame staff associations, but not in any sense were they unions. Any attempts at industrial organisation were actively discouraged as being inimical to the public service ethos.

For someone of Mick’s ilk, with his keen commitment to fairness and equity, that was something of an affront. He was instrumental in the formation of what was to become the Administrative and Clerical Officers’ Association (ACOA). By the time I joined the ACOA in the late seventies, it was a ridgy didge registered industrial organization, albeit a pretty weak one. In my time, industrial activism was still frowned upon. Indeed, in 1981-1982, when I was a member of its National Council, Malcolm Fraser had a red hot go at destroying the ACOA. So you can imagine what it was like in the 1950s for the pioneers of ACOA – hardly a career enhancing move. Still, Mick and his comrades weren’t deterred and, among other things, he founded the ACOA monthly journal and edited it for 10 years.

Doing that sort of thing is pretty hapless: obviously all in your own time, obviously unpaid. To do it for 10 years was quite a feat, especially when there are other really important things going on in our life, such as family. Mick was a man characterised by his faith.

In essence, he belonged to 3 tribes: Catholicism, which was a deep and abiding faith, Labor and the Bombers. Actually, there was a fourth tribe: his former brothers in arms of the 2nd/5th, men who were bound together by mud and blood. With the Public Service hierarchy tending to be Protestant, Liberal and supporting the Blues (or the Filth, as many Bomber supporters would think of Carlton, after cheating the salary cap for years and cheating Essendon of the 1999 premiership), these predilections weren’t necessarily career enhancing either.

It does seem unimaginable today, but in the ‘40s, 50s and 60s Australian society was divided along sectarian lines. In the Public Service, there were a few Catholic outliers such as the Department of Trade but Treasury was very much a Protestant bastion. Vestiges of that sectarianism persisted until well into the 1970s. As they say, the past is a foreign country. Until some time in the late sixties, a married woman could not be a permanent public servant, only part time which was the status of Mary. She worked in the Public Service but was not permanently employed so lacked security and, importantly, any superannuation entitlements.

It would undoubtedly be a concern to a person of Mick’s conscience that in ways we seem to be revisiting aspects of our darker past. For example, while the official unemployment rate in Australia is about 5.5%, which would seem pretty good in a modern economy, the official definition of “employed” is 1 hour of paid employment a week. That definition masks very significant under-employment. There’s also the increasing casualisation of the workforce, with attendant job insecurity and lack of employment benefits, as well as exploitation of vulnerable workers, as we have seen exposed at 7/11 and Dominos and even at a retail giant such as Coles. And God knows what he would think of the rise of reactionary populism, here in Australia and elsewhere.

It’s certainly not the kinder, gentler, fairer society Mick envisaged and worked towards. It’s actually getting meaner and more hard scrabble.

Mick and Mary lived the first decade of their life together here in Melbourne and its where their own family began. Ro came along in 1951 and Jenny in1957. I’m obviously not qualified to speak of Mick’s qualities as a dad but I imagine he brought the same enthusiasm to fatherhood as he did to everything else.

For the first decades of our Federation, the Public Service was based in Melbourne. I’m not a huge fan of Robert Menzies, and neither was Mick, but Menzies, to his credit, had three great nation-building initiatives: 1) The creation of the Reserve Bank of Australia 2) The expansion of the university sector 3) The establishment of Canberra as a real national capital, when he established the National Capital Development Commission to build the place and he began moving the Public Service to populate it.

So, it was that in 1954 the Sheehan family relocated to Canberra in the first wave of Public Service transfers. Before moving to Canberra, Mick stored under my grandparents house in Beatrice Ave Jordanville a cache of weapons that he had souvenired from the war, which made my grandparents a little uneasy.

A couple of years later, Mick’s soon to be brother-in-law, Tony Ferlazzo, helped my granddad build a garage. Being of Italian descent, Tony was naturally very good at concreting and he laid a thick concrete slab and, at my granddad’s instigation, buried within that slab was Mick’s souvenired weapons. Mick was not impressed. When I moved to Canberra in 1973, it had a population of 120,000 and was pretty Hicksville, so you can imagine what it was like in 1954, some 7-8 years before Lake Burley Griffin filled: in 1954, the lake was, I think, market gardens.

The Sheehans first lived at the Hotel Acton, which is now a flash residential and hospitality precinct, but would have been pretty cramped and ordinary in those days. After 3 months they moved into a proper house in MacGregor Street Deakin. As Mick told it, even the housing process was stratified. Rank and file public servants were allocated smaller houses in less prestigious suburbs – though you would never call Deakin less prestigious now – and the wallahs and mandarins got bigger houses in more prestigious suburbs, presumably the likes of Forrest and Manuka. Meanwhile, your common day labourers doing the construction got huts in the Causeway, a sort of ghetto, housing mainly newly arrived Displaced Persons (refugees) from Europe and people who had worked on the Snowy Scheme.

Again, you see Mick’s social conscience kicking in, the old Catholic Action agenda of justice for and the betterment of all, not just the few. After Mass at St Christopher’s in Manuka on a Sunday, Mick would go out to the camps – often with the kids in tow - and assist the men in whatever way he could: filling out forms, negotiating health needs, advocating on their behalf with authorities. And he taught himself Italian so he could act as a more effective intermediary and advocate.

Mick wasn’t motivated by any sense of Christian charity but by Christian compassion and an inherent sense of Christian duty. As if this wasn’t enough – establishing a new home, working, union activity, social work with refugees, raising a family with Mary – Mick was ingenious in finding other ways to fill his spare time. He enrolled at Canberra University College - which was then affiliated to Melbourne University and is now the Australian National University (ANU) - and undertook a Bachelor of Arts with a psychology major – perhaps to better understand the capitalists?

Mick was one of the driving forces behind the establishment of the ACT Amateur Athletics Association and he remained a cross country runner himself. He liked tramping around Stromlo Forest, dragging Ro and Jenny with him - I imagine to their utter delight. Just to keep the old mind ticking over, he attended Latin conversation classes at University House Acton.

Mick’s spirituality found a new direction with a growing interest in meditation, which is mainstream these days but pretty radical back then.

By the time I arrived in Canberra in 1973, to attend ANU, Mick had retired from the Public Service – to be frank, I don’t think he any longer had the time to work. He and Mary showed me unending kindness and generosity. They drove me around Canberra pointing out the hotspots, they invited me into their home and fed me regularly, which was pretty important in my first year, given I was basically broke and not living well.

Over the years, Mick and I developed what I think was a good and close relationship, a friendship. We discussed books and politics, film and life in general. I admired him for his insight and wisdom, his humour and, most of all, for his values. He was a profound influence on me.

In retirement, Mick was as active as ever. He and Mary travelled some, he regularly attended the Olympics and competed himself in the Veterans Olympics. He also participated a number of times in the Sydney City to Surf race, until well into his sixties.

In 1978, Mary, his wife and life partner, passed away. This was obviously a great loss but he was sustained by his own deep faith, the love and support of his daughters, and the joy he took in his growing brood of grandchildren. It pleases me that he got to meet my own boys, although not my daughter Bridget. In fact, Gabe, the officer cadet, has an inscribed volume from Mick about the Eureka Stockade – there’s some sort of family connection which I don’t recall – which is something of a rare edition.

Another one of Mick’s hobbies was collecting first edition Australian books. Mick remained a heavily engaged, active person for the 20 years of his life after Mary’s passing. He was deeply involved in the Commando Trust, which published the remarkable volume from which I quoted earlier.

He was involved in Legacy and did a lot of work with the Australian War Memorial, which must be so grateful that he ignored regulations about making movies on active service and that he kept intact his battle kit.

In this later period, Mick hosted a couple of movie nights of his own home movies, the first of which I approached with some trepidation, thinking it might be like a slide night of someone’s holiday snaps. They were great events, in fact: colour footage of the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, kids cavorting in backyards and that sort of stuff.

Mick passed away, in bed, typically reading a book. Mick left the war, as he said, with no thanks. But he left this life with many thanks and the gratitude of his family and friends and associates, for his life of service, for his goodness and for his contribution to the greater good. So tonight, we say thanks for the life and times of Michael Lawrence Sheehan. To Ginger Mick.