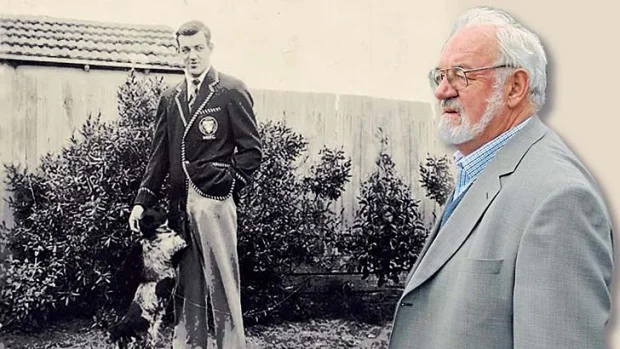

3 April, 2014, Kew, Melbourne, Australia

As a boy Jack lived with his family in Brighton and helped his Dad with gardening. Anyone who went to Acheron Avenue would know that Jack learnt a thing or two about that art. He designed and planted what was one of the best gardens in Camberwell.

His Dad, Harry, a keen student of the horses and a hopeful punter, invested any small amount of money he could manage on the odd nag. There was no TAB in those days so the local barber who attended to the Clancy family doubled as an SP bookmaker. Doubtless, he was one of John Wren’s franchisees.

One Saturday they were gardening in Brighton when Jack’s father got a tip from the owner of the horse. Jack had to take 5 shillings to the barber to put on Saint Warden before the 3pm race. That was fine; only a ten minute walk away so Jack headed off with plenty of time. But when he got to the level crossing at New Street, the gates closed. He waited for the Sandringham bound train to come and it roared past but the gates still wouldn’t open. There was a train coming from the other direction.

Of course, by the time Jack made it to the barber, the race was over and Saint Warden had won at the juicy odds of 10/1. Back he trudged with the 5 shillings aware that a win would have been five pounds. More than his Dad could earn in a week at the Council depot. He was expecting the wrath of God but, when he told him what happened, Harry Clancy said “Ah well. That’s life John, that’s life.”

Jack must have told me that story a dozen times over the years and it’s interesting that, despite his love of sport, he was never a gambler, just a devotee of footy tipping where he prided himself on injecting knowledge into the equation and (Pause) just a little bit of luck.

Fast forward nearly half a century to the venue at Martinis Hotel in Rathdowne Street, Carlton now an abandoned building opposite the Housing Commission flats. On Thursdays Jack, Laurie, Paul and I and sometimes Jack Hibberd and the lawyer, Phil Molan, would have lunch and waste the rest of the afternoon playing pool.

When we first arrived, we were given the cold shoulder by the locals. We were outsiders but one of them recognised me from my time at the Pram Factory and the nearby Stewarts Hotel which we frequented. Grudgingly, we were allowed access to the pool table in between their games.

Some very funny fellows were there, all with nicknames. Harry Horsetrough was an able teller of tall tales from Tasmania where his family reputedly owned a chain of hotels which suffered losses due to Horsetrough constantly dipping his nose and hand into the cash registers. Hence the nickname. The family exiled him to Melbourne and dribbled him a stipend for booze and horses.

Horsetrough’s great mate, he was fond of telling us, was Christopher Dale Flannery, aka Rent-a-Kill, a contract killer named in various Underbelly type crimes and also a casual and brutal enforcer for [celebrity footy tycoon ].

We later learned Horsetrough had done time for embezzlement but then most of his mates in the pub had similar records. We were often introduced to folk just released from Pentridge including a couple of murderers, retired. Apart from one bloody fight over a contested pool table booking, it was pretty quiet and we were tolerated.

On Thursdays about once a month a bloke who people called Merv the Perve came in the side door, looked cautiously around for strangers and off duty coppers and then shouted out things like “Shoes, boys: Julius Marlowes, Hush Puppies, Ezywalkin, House of Windsor come and get em. Straight off the wharf”. Then he’d come in carrying boxes from his panel van and shoe the whole bar for cash. No questions asked.

We never bought this stuff even though Horsetrough and Lindsay Loophole told us it was “Right as rain. Right as rain, mate. Look, the Perve used to be a copper. He’s as clean as a whistle. No worries.” Oddly, that made us feel less secure.

Lindsay was particularly friendly with Jack because he’d been a footballer who, like Jack, had played a bit of VFL at Fitzroy. They swapped notes from their past glories and Lindsay made a reasonable profit by playing and beating everyone at pool. He also had multiple contacts among prominent Sydney and Melbourne racing identities and a reputation for tipping long odds winners.

Merv’s top offer one year close to Xmas was camel hair overcoats. He rushed into the bar with a stand holding about ten of these very flash overcoats and called for offers but would settle for fifty bucks each.

This time Jack, the sartorial flying wedge of the bar, was sorely tempted and I said “Be careful, Jack; they’re hot”. Laurie, quick as a flash, said “Doesn’t matter; he won’t wear it till winter” and got a big laugh from the bar. But no sale. The next day there was news of a break-in at a Chapel Street shop which was missing thousands of dollars worth of clothes including camel hair overcoats

The following Thursday Loophole sidled up to Horsetrough and whispered something to him. Soon the whisper was all round the bar – Loophole had a horse running at Bendigo in an hour and it had been set. Lost its last three races by a total of 30 lengths due to the services of a jockey known around the traps as Handbrake Harry. If we got on quickly, we would get 33/1.

Loophole’s SP connections were offering those odds and we could all join in and he would place the bet. Horsetrough pulled out a giant roll and gave $200.00. Others put in $50 and Laurie and I put in $20each. Jack, still carrying the burden of Saint Warden, was reluctant but Lindsay worked on him and finally he contributed $50.00. I reckon Loophole left the pub with about $500.00 when he headed for his SP.

We gathered around a radio and listened to the race which our nag won in a photo finish to great cheers from the bar – fifteen grand richer. We waited for Loophole to return with the dough but no show. We waited and waited. Two days later Horsetrough told me Loophole had done a runner and as far as he and Rent-a-Kill were concerned he was dead meat. “We know where he is, Johnny.” said Horsetrough. “He’ll be under the Mascot tarmac soon or’, he said delightedly of another well-known method of body disposal, “In the Altona Simsmetal compactor driving a crushed Holden into the Jap steel furnaces.”

And, warming to his task, shaking his head, laughing, spilling beer on his camel hair coat, “ Loophole will be back in Australia as a window handle on a Toyota, Jeez! Wouldn’t it be good winding him up.”

Jack was not so worried about his money but he did think Loophole’s chances of a quiet life in Melbourne were less certain than his afterlife as a car part. And, of course, his own experience at the level crossing decades ago was still a caution about this gambling caper. There were now two examples of misery.

I lost track of the Martini crowd apart from occasionally bumping into Horsetrough raging around Carlton still fuming about the six grand he’d lost.

Two or three years later I was on the Gold Coast with Max Gillies doing a show at the Casino. To get to the stage, we had to walk through the gambling area past the pokies with Max made up as Bob Hawke and suddenly I spotted Loophole. He went white. We calmed him down, talked, reminisced about the old days, the characters and I didn’t mention the bet.

Horsetrough, he knew had died and it was Rent-a-Kill, rather than himself, who was supporting the Sydney Airport tarmac. “How’s Jack?” he asked, “Great footballer. Terrific kick, you know.” I said he was fine and we went to leave. Hawkey was squawking his insistence about getting on stage: “Maate, maate – we’ve got business to do. . . . “ and so on.

Loophole stopped me and pressed a fifty dollar note into my hand saying “Give this to Jack, will you, Johnny. He wasn’t really a betting man. Not really. A good bloke, your mate, a real good bloke.”

And he was. A real good bloke.

Vale Jack.

A man for all seasons.