20 March 2024, Carmelite Monastery, Kew, Melbourne, Australia

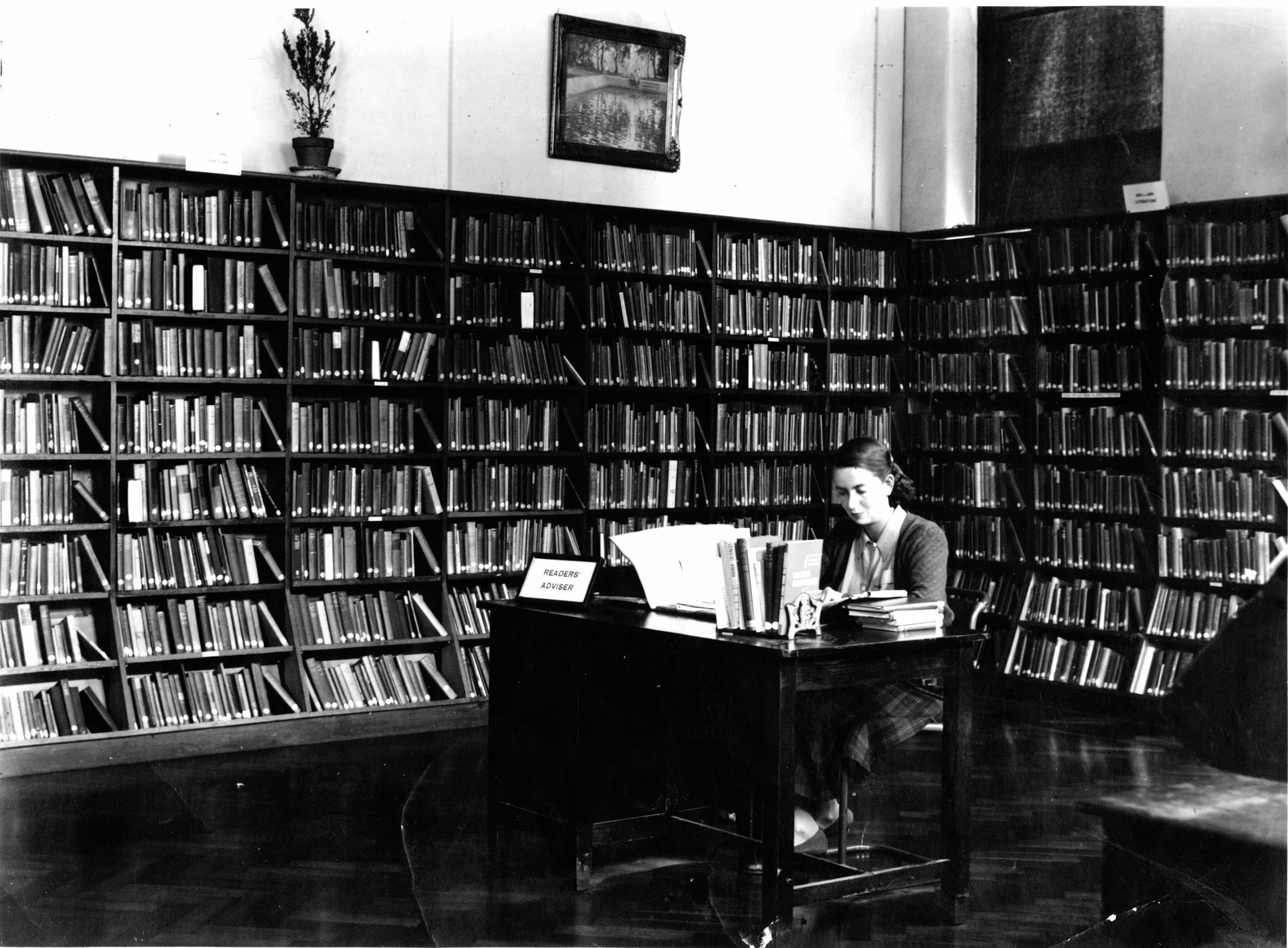

It’s no surprise that, as Jo mentioned, one of Mum’s first jobs was a reader’s advisor because she was a wide ranging and extremely open reader. Despite her genteel air, Mum was not put off by challenging subject matter. In the last few years, my son Rory recommended Irish writer Sally Rooney’s Normal People and she consumed this novel of young adult sexuality, depression and family violence with great attention. Only a few months ago she read Richard Flanagan’s Question 7, a memoir about the strands of chance and history that allowed for Flanagan’s birth, including his father’s experience as a slave labourer near Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped. For her 97th birthday my daughter Honor gave her the actor Gabriel Byrne’s Walking With Ghosts, a memoir of growing up poor in rural Ireland and discovering the transcendence of the stage, as well as revealing Byrne’s struggle with alcoholism and depression. Mum discussed the book in some detail with Honor, delighting in Byrne’s distinctive Irish voice, considering his personality, and admiring the lyricism of his language use.

Going back a bit, I remember Mum describing a family holiday at Dromana, where her adolescent protest and ennui was expressed in a sullen refusal to do anything except read War and Peace, even on the beach. She was fond of black humour in a book – a trait she shared with our father Maurice and passed onto all of us. In the last month of her life I lent her a book called O Caledonia by Scottish writer Elspeth Barker and though she did not have the strength to finish it, we talked about its brilliant sentences. And Mum was not bothered by the fact that, in the early pages, we learn that the heroine Janet was disliked by her parents, and fatally stabbed in a mouldering Scottish castle at the age of 16, an event which – believe it or not – is described with comic verve. Mum loved the characterisation of Janet’s nanny, a tough-as-nails Scot who had ‘a face like the north sea’. She was a big fan, too, of the William books by Richmal Crompton, a funny, ironic children’s series about a chaotic 11-year-old, leader of a gang called the Outlaws. Then there was Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis, a black comic tale about a reluctant history academic steeped in alcohol and extra marital affairs.

Mum loved the anarchic energy of Edward Lear’s poem The Owl and the Pussycat, with its unlikely lovers dining on quince and slices of mince, which they ate with a runcible spoon.

And I remember her delight in reciting an A A Milne poem for children entitled King John’s Christmas, about a king who longs for Father Christmas to leave him a present, but appears unlikely to get one, because he is – apparently – very unlikeable.

The first line is the following: King John was not a good man, he had his little ways, and sometimes no one spoke to him for days and days and days.

Just what King John’s little ways are, is not illuminated, It is in this gap, but also the fact that Father Christmas does, ultimately, take pity on him and deliver one longed-for present - a great red India rubber ball bouncing through his open window at the eleventh hour - that provided the humour for Mum. Humour bound up with an awareness of human frailty and of our propensity for compassion. Frailty that we all have and compassion that we all try to find within ourselves.

Philippa Ryan was Readers' Advisor at the State Library of Victoria, 1950s

Mum valued literature not for its own sake, though perhaps for this too, but for the window it offered onto people. She liked to analyse and discuss each story I published in some little- read literary journal and each made its way onto the section of her bookshelf dedicated to me.

At the age of 95 she read my novel not once but twice, almost certainly the only reader to do so. She said she would discuss it fully after the second reading as she wanted to consider properly the book’s structure and themes. She also seems to have recommended it to everyone in her circle, including her podiatrist.

For many years she was in a book group with her sister Brenda and her great friends Kaye Cole and Faye Courson. Kaye, who was known for strong opinions, would sometimes dismiss a book with little compunction, but I don’t remember Mum ever doing so.

Such willingness to go where a book took her reflected her curiosity, her compassion, her profound interest in people and how they functioned in the world. Books mattered to her, not as an escape from the world but as a way to understand it and those who inhabited it.

In her last days her book pile included Andre Agassi’s Open (she was a big tennis fan), Edward St Aubyn’s novel Never Mind, Robyn Davidson’s memoir Unfinished Woman and Gabbie Stroud’s The Things that Matter Most, a novel about the trials and tribulations of a modern primary school, probably because she wanted to keep in touch with the day-to-day life of her grandson Finlay, who was embarking on a teaching career.

Just before she died I read Mum Tyger Tyger by William Blake, a poem I remember her reciting to me as a child.

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

This seems fitting subject matter. For all her gentle qualities, Mum was a courageous woman who embraced the complexity of life. She was fascinated with the world for what it was – humorous, dark, wondrous, sometimes frightening and often complex – but always interesting.

I will miss her greatly.