5 September 2016, Kiama, New South Wales, Australia

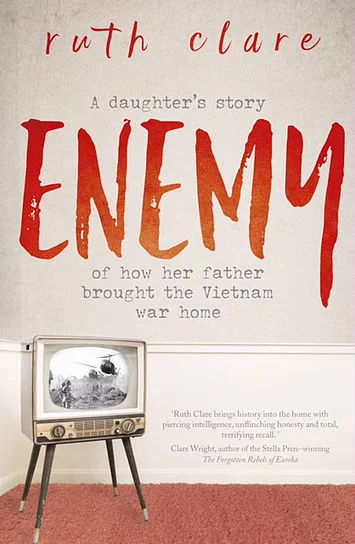

My name is Ruth Clare. I am the author of ‘Enemy: a daughter’s story of how her father brought the Vietnam War home’. It is a memoir of my childhood and an exploration about the impact of war on veterans and their families.

I am here to speak to you today because this is a day about children – specifically about children who have suffered abuse and neglect – and I was one of those children.

Did you know that, according to The United Nation's Convention on the Rights of the Child, all children are born with the same fundamental freedoms and inherent rights as adults, though their vulnerability also entitles them to special protection?

Children have THE RIGHT to be protected from all kinds of abuse and violence. They have THE RIGHT to protection against all forms of neglect, cruelty and exploitation. They have THE RIGHT to affection, love and understanding.

According to the Convention, these are not lofty ideals, these are basic rights.

Unfortunately, we all know it is not always possible to shelter children against violence and abuse, especially if that abuse is perpetrated by the very parents who are meant to be acting as guardians and protectors. It IS possible however, for us all to defend a child’s RIGHT to be listened to and to have their opinions taken seriously when decisions are being made about their lives.

In The Body Keeps the Score, Dr Bessel van der Kolk says: “Trauma almost invariably involves not being seen, not being mirrored and not being taken into account.”

I wrote my book because I grew tired of not being seen. I am standing here before you today because I want all of the kids out there who have had childhoods like mine to know that they have the right to tell their story. They have the right to be heard.

Ruth (wearing goggles) with older sister Kerstin

For the first five years of my life, I grew up in Brisbane, where it is warm and sunny 260 days a year.

This photograph of me with my sister Kerstin (I’m the one wearing the face mask) was taken nearly forty years ago in the back yard of the first house we lived in – a typical house of the seventies – double storey brick on a large block – in one of Brisbane’s outer suburbs called Strathpine.

The majority of my days before I went to school were spent at home alone with Mum, splashing in the blue-tarp pool on the couch grass of our yard. Dad spent the most of his time out of the house at work. But sometimes he was at home.

It was at around the age I was in this picture that I laid down my first fully formed memory.

I was hiding under the table in our dining room pretending to be a secret agent when Dad came to a sudden stop in front of the place where I hid.

“Jesus Christ. Girls!” he yelled.

My stomach was instantly sick. I didn’t want to get in trouble again.

My sister, Kerstin, and I lined up in front of him, the way he had taught us to.

He started jabbing his finger at the wall.

“What’s this?”

My heart dropped down to my toes. He was pointing at the label I had peeled off my box of tic tacs and stuck to the wall.

I looked at where he pointed pretending I was seeing the label for the first time and tried to make my voice sound interested and surprised.

“It’s a tic tac sticker.” I said.

“I know it’s a tic tac sticker. What I want to know is who put this sticker on my wall?”

Kerstin gave me a small bump, wanting me to own up.

“Well?” Dad said.

“It wasn’t me.” Kerstin said

I knew I should confess, but I was so scared. I though maybe if we both said we didn’t do it then no one would get in trouble. “It wasn’t me.” I said too.

Dad hit Kerstin first, on the shoulder, then me, on the ear.

He asked again. “Who stuck the tic tac sticker on the wall?”

“I didn’t do it!” Kerstin’s said.

Now I knew I needed to own up, but still I couldn’t make myself. “I didn’t do it either.” I lied again.

Again he hit us both. Whack. Whack.

Inside my head I started chanting: sorrykerstinsorrykerstinsorrykerstin.

Dad bent down and grabbed us by the arms and started shaking. My head rocked back and forth on my neck and the world blurred into kaleidoscopes. As his shakes grew harder, I knew I couldn’t let Kerstin take any more of this no matter how scared I was.

“I did. Me.” I said.

Dad threw Kerstin into the corner of the room and got a better grip on me so I couldn’t run away, then started laying into me, my body his drum as he beat home his words.

“I am not hitting you because of the sticker. I am hitting you because you lied!”

The rage pumped out of him, into me, filling me with anger bigger than my body could hold. A booming voice filled my head. Liar! Liar! You say you are only hitting me because of the lie, but you hit Kerstin too, and she didn’t lie.

I wriggled free and ran away trying to hide under the couch. He chased after me, grabbing my legs and pulling me out. My hair caught on the springs of the couch and a chunk was ripped from my head. I gripped the couch but he held me upside down, shaking me until I let go.

When I did he put me on my feet and started pounding me again for daring to run away.

Whack. Whack. Whack. Whack.

I no longer felt his blows land. The beating of my heart and the whooshing in my ears was all I knew. I didn’t care what he was saying, I had to get away. I ran to my bedroom and dove under my bottom bunk, but barely managed to conceal myself when I felt his hands grip both my legs.

Just as he was about to drag me out, Mum appeared at the door.

“Doug! Stop it! Her voice was a scream so wrapped in terror it was barely more than a whisper. “You’re going to kill those kids one of these days!”

He let go. It was finished.

I stayed under the bed, turning around and pressing my face into the wall, hugging it. I wished I could crawl inside that wall: so solid and safe.

As my tears disappeared, I drifted into the blue-flowered wallpaper, becoming one with the green leaves and blue dots, and a soft, dreamy fog stole over me. I couldn’t tell if I was asleep or awake. I don’t know how long I stayed there, but when I became aware of my body again I was shivering and sore where the wooden floor pressed my bruises.

Lying on the bed I heard Kerstin enter. Her soft hand touched my back. I didn’t turn around. I didn’t deserve her kindness when it was my fault she been hurt.

Eventually I faced her and started crying saying, “I’m sorry,” over and over.

“It’s all right,” she said.

I didn’t believe her. I was the worst kind of person, sacrificing someone else to save myself. I turned back to the wall, “I’m fine now. You don’t have to keep being nice to me. I just want to lie down.” I needed to be alone if I was going to make myself strong again.

The next footsteps I heard were Dad’s.

His voice was small and quiet when he spoke. “Ruth.”

I kept facing the wall, pretending to be asleep.

“Ruth” His tone was more insistent so I turned around.

He stepped into the room with his arms outstretched. “Give me a hug.”

I stayed where I was.

“Come ’ere. Don’t be silly.” His voice was teasing, but I could hear the edge underneath it.

I was desperate to say no. I wanted him to know I truly and deeply hated him and would never forgive him, but I didn’t want to get in any more trouble. I walked and stood stiffly in front of him, arms by my side.

As he hugged the marble statue I offered him, he murmured into my ear. “I’m sorry, love. But that hurt me a lot more than it hurt you.”

I boiled with the unfairness of his words, heart pounding in response, but kept quiet until he let me go.

“Are we okay?”

As if I had a choice. “Yes, Dad.”

How would you feel if this happened to you?

I just want you to consider this for a moment. To really put yourself in the shoes of the child and ask yourself : How would I feel if this happened to me? Because if you can answer that question, you will know how the children you are dealing with who are unlucky enough to be in situations like this, are feeling. And if you felt that way, how would you want people to treat you?

This is how little I was when I made the mistake of peeling a label off a box of tic tacs and sticking it to a wall. This is how little I was when I lied to try to avoid getting in trouble. This is how little I was when Dad treated these transgressions with that level of violence.

This was my first memory, and among the most vivid I have, but it is not my only memory of Dad’s violence. My childhood was spent walking along a razor edge of expectations that were impossible to meet. There was no room for mistakes. No allowance for the fact that I was small and learning.

Leaving a bike in the yard. Tripping and hurting myself. Running through the house. The impulses of early childhood were the things most likely to evoke his rage. Sometimes it was just a few slaps. Other times he would lose control.

I hated him for the way he treated me. Passionately. Deeply. But though I wanted to punish him, tried to will myself into feeling only rage so I could hurt him the way he had hurt me, I loved Dad too. Not just loved him. Twisted myself in knots for him. Kept trying to make myself good, better, best, to prove to him that I was worth loving back.

See he wasn’t always violent. When he was in a good mood, he could light up a room. He could be funny, smart, warm – and he gave the best hugs. When he shone his light on me, something inside me unfurled and grew. It felt like many of the good parts of me were the good parts of him.

Loving him the way I did, the way I am sure most people here love their parents, made it hurt all the more when he lashed out.

I share this story with you because, though it is my story, it is also the story of so many other children. Children too small to stand before you today. Children too young to know how to put their experience in words. Children too scared to speak out.

According to the Alannah and Madeline Foundation, 1 in 4 children in Australia have experienced family violence

Their figures show that there are over one million Australian children currently living with violence in the home. Many of these kids are living in fear, hiding their bruises and wondering what they did that was so wrong that the person they loved most in the world needed to hit them.

These are shocking figures: a crisis by anyone’s estimate. Yet the conversation around domestic violence up to this point, has largely framed the problem as something that happens between a man and a woman. This, despite recent national data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare finding that between 2008 and 2010, the leading cause of death among children aged 0-14 years was injury, and the third most common type of injury (after transport-related deaths and drowning) was assault.

If Australia’s children were dying in these numbers from a disease, people would be screaming for a cure, yet the issue of child abuse is rarely discussed. Why is this?

According to The United Nation's Convention on the Rights of the Child, “Children have the right to have their views heard, considered and taken seriously in a way that is appropriate given age and ability, especially when decisions are being made that affect them.”

I cannot think of a single time during my childhood when I felt my views were heard, considered or taken seriously. It never occurred to me that they would be.

When you are a child your experience is constrained within the world your parents show you. You rely upon them to be your teachers and guides. If they teach you that you are worth nothing, that your pain and sadness deserves no recognition, that is the lesson you learn. If they fill you with their anger before you have had time to make your own sense of the world, it becomes fused into your understanding of how the world works and the world becomes a dangerous place.

When the world can’t be trusted, it doesn’t occur to you that there might be adults out there who could help, and that there are avenues of support beyond the four walls of your home.

Ruth, her father, and younger brother David

This is me with my Dad and my brother David. We are standing on a beach half an hour outside of Rockhampton, the town we moved to when I was five. This photo was taken about a year before Dad left our family to live with another woman and her children.

A few days after he had packed up all his things and left our home for good, I came home after school and discovered a strange new sound coming from the side verandah of our house. It was quiet and repetitive, kind of like a dog whining. I crept toward the noise to investigate, telling myself I could run away if I needed to.

What I found was Mum laying sprawled face down on the floral covered foam sofa we had for “guests” who never came. The foam sections of the couch had come unstacked making her position teetering on the edge, spilling over onto the floor, look even more precarious.

She was crying. More than crying. She was sobbing. Great wracking howls of despair from the pit of her stomach.

The four-litre cask of Coolibah Riesling on the floor next to her thickened the air with the sweet, rancid smell of fermented grape.

“Mum…” I said.

She lifted her head and turned toward me. Her whole face was puffy, with eyes nearly swollen shut. Her nose was red and almost twice its normal size. Snot was smeared across her cheek.

She reached out and grabbed tightly onto my hand. Her palm was sweaty in mine. “I’m so sorry.” Her voice matched her face, ragged and broken.

Tears flashed to my eyes. What was she sorry for? I kept holding onto her hand, twisting my arm into an unnatural position as I bent down, not wanting to let go. I gave her back an awkward half hug but her sobbing escalated so I moved to stroking her springy hair again and again.

I was sure this had something to do with Dad, but I couldn’t figure out what. During the past few days no one had mentioned him. To me, the house felt the same way it did when he went away on a fishing trip. We had watched extra television, even eating our dinner of frozen pizza and two minute noodles in front of it – so much more relaxing than chops and veges at a silent dinner table bang on the stroke of 5.30.

Bedtimes were less stressful too. The night he left I had taken myself to bed at 7.30 p.m. as usual, but the next night I had pushed it until eight to see what would happen. Nothing. Last night I had stayed up until nearly ten o’clock and Mum hadn’t said a thing.

With the tension out of the air, for the first time in my life I felt I could breathe.

Keeping up the rhythm of pats on her head, I looked at Mum’s weeping form. It had been days since Dad left and there hadn’t been any crying so far. Why now? I tried to come up with things about Dad she might be missing, but drew a blank. The only thing I could think of was maybe she thought he was coming back.

“Don’t worry Mum.” I used my kindest, most reassuring voice. “He’s not coming back.”

Her crying picked up intensity and she turned her ruined face to me, speaking brokenly through her sobbing. “I-I-I kn-know that. Th-that’s w-wh-hy I’m cr-cr-crying.”

I was dumbfounded. Mum actually wanted Dad to come back? Didn’t she remember all those times he hit us kids? I wanted her to be happy, but there was no way he was coming back here; not if I had anything to do with it.

Maybe she thought that now Dad had left she had to do everything on her own. But she didn’t. She had me.

“It’s okay mum,” I told her. “I’m here. I won’t ever go away. You cry if you need to. Don’t worry about it.”

I thought if I could be supportive enough, she would stop crying. I kept stroking her hair, but I couldn’t think of anything more to say. As her crying continued unabated, I grew more and more helpless.

How would you feel if this happened to you?

Mum had never been a big drinker, so initially I thought the drinking would be a temporary thing, but as the weeks clicked over into months I realised I was wrong. It was hard to understand her devastation, because the main thing I thought about Dad leaving was that his time terrorizing us had ended. It turned out I was wrong on that score too. We all still had one more night of terror to face.

The night he came back I woke from a dream, unsure if the noise that had roused me was real or imagined. I lay in bed, listening intently.

“Help! Help!” I couldn’t tell whose voice it was, but someone was in trouble.

I was out of bed and down the hall before I even felt my feet touch the ground. In the darkness I nearly ran into my little brother David.

“Help! Somebody help!” This time there was no mistaking the voice. It was Mum, her voice a muted scream.

I ran to the brightly lit kitchen, struggling to understand what I was seeing.

Dad had Mum pinned to the ground. He was kneeling on top of her, with the weight of one knee pressed across her thighs, his hand on her shoulder. It didn’t make any kind of sense. I hadn’t even seen Dad since he had left us, and in all the time he had lived with us, he had never hit Mum. Why now?

I didn’t know what to do so I ran over and hit his shoulder, shoving to try and unbalance him as I yelled. “Get off her!”

When that didn’t work I tried to look after Mum, putting her head in my lap and asking if she was okay. Dad hated that, so he picked me up and threw me across the room. I slammed into the dishwasher, smashing my head on the bench above it. He resumed his position on top of Mum. I stayed where I was, wanting to help, but wary of being hit again.

When he threatened to scoop her eyeballs out with the cap off a beer bottle I knew I needed help, so I took my brother and ran next door to a neighbor. I told her Dad was trying to kill Mum and asked if we could call the police.

Though I felt like I was going to jump out of my skin with how revved up I was, I had also been taught to be polite to our elderly neighbours. So when she took her time looking through the phonebook for the number of the local station, then reported “some kind of domestic disturbance” I stood by and let her, though I felt like dragging her over to the kitchen at my house so she couldn’t look away from the harsh reality she was trying to coat in a polite veneer.

The first

This was the first person I had ever told about the violence going on at home. I told her my Dad was trying to kill my Mum. She had downgraded the situation to a “domestic disturbance” not even worthy of dialing 000. It certainly didn’t feel like she took my view seriously.

When I saw the sirens I raced back home, just in time to see Dad open the door to the police.

Before Dad could say anything I jumped in. “Dad was hurting Mum and he doesn’t even live here anymore. He’s not meant to be here. I want you to take him away.”

The policemen looked at Dad. “Is this true?”

He nodded without looking up.

Their attention shifted to me. “Is your Mum here?”

At this stage I didn’t know if Mum was dead or alive, but after I called her she emerged from the bedroom relatively intact.

“Do you want to press charges against your husband?”

She shook her head without speaking.

When they asked if we wanted to stay at a shelter in case Dad came back I convinced Mum it was probably a good idea. In the police car on the way to the refuge I kept expecting the officers to ask about what had happened. Instead they asked what grades we were in and the name of our budgie.

It felt like they were showing us what we were expected to do. Act normal. Put it all behind us. Not dwell.

The second

These were the second people who knew something of the violence going on at home. They didn’t ask us if we were alright. They didn’t offer to put us in contact with any support services. They dropped us off at the shelter that would be our home for the weekend and that was the last we saw of them.

During the whole of my childhood it had never occurred to me to reach out to anyone for help with what was going on at home. The way the police responded to our situation seemed to confirm that, apart from a place to escape to during a period of peak violence, there was no help on offer.

After we settled into our room at the shelter Mum said, “I might go and visit a friend of mine in a little while.”

I was taken aback. Mum didn’t have any friends. And if she did, she certainly didn’t drop by for visits.

‘What friend?’ I asked.

Her eyes darted around the room and her voice sounded deliberately casual. “You remember that man I went out with last night? He just lives around the corner from here.”

“Oh.”

Mum had gone on her first date since Dad left the night before. After everything that had just gone down with Dad I hadn’t thought to ask her anything about it, but it was obviously still on her mind. I wanted to stay supportive, but I was horrified she expected us to stay in a safe house with a bunch of strangers for even a moment without her. David was only nine-years-old. I didn’t see how it could even be legal to leave children alone at a shelter.

Despite all of my efforts to support her, it didn’t make any difference, because I wasn’t a man. I wanted to scream at her, “We are only at this women’s shelter because I thought of calling the police. You don’t need a man to save you. I have already saved you. And while I am at it, why is it that when Dad beat you up it was important enough for all this, but when he beat us up you didn’t do anything? He hit me hundreds of times and you never once tried to drag him off me. You never once called the police for me. Why is that? What makes you so important?”

But I didn’t say that, because I knew there was no point.

The third

The third adult I told about the violence at home was my teacher. I had taken a box of fundraising chocolates to the shelter and over the course of the weekend, I had eaten the entire box. I didn’t have the $37.50 I now owed. I decided the best way to get out of paying might be to tell her a lie, wrapped up in the truth of my experience over the weekend.

I pulled my teacher aside after English class. “Sorry to tell you this, but my father tried to kill my mother on the weekend and we had to stay in a women’s shelter.”

She let out a gasp.

“Yeah it was pretty bad… and the worst thing, while I was there someone stole the box of chocolates I’m meant to sell. I’m not going to be able to give you any money for them.”

She stared at me a few seconds too long then her eyes darted to the window.

“It’s alright, Ruth.” Her voice was small and her eyes didn’t meet mine.

“So I don’t have to give you any money for them?” I asked.

“No. It’s fine,” she said.

Though the main reason I spoke to my teacher was to get out of paying for the chocolates, I was also testing to see what would happen. I had always thought of school as my safe place. The adults there mostly seemed responsible and reasonable. If they thought what had happened to me was a big deal, then maybe it was.

But my teacher did nothing. She didn’t ask if I was okay. She didn’t pull me aside after lessons to see how everything at home was going. She didn’t ask if I wanted to see a counselor. This was the third grown up outside of my family I had told that my Dad had tried to kill my Mum. Not one of them asked how I was. Not one of them asked if Dad had ever hit me.

How would you feel if this happened to you?

I had spent a lot of time during my childhood waiting for the moment when someone would finally see me. They never had, and as far as I was concerned, the way these grown ups responded to my story showed me they never would. Lucky for me, I had never let the grown ups in my life define my reality.

Since ever I could remember, I had created a parallel life to the one I was living. A fantasy world where I was a star. People paid attention when I spoke. They cradled me softly when I was hurt. And they told me I wouldn’t just be okay, I would escape the cruddiness of my life and make something of myself.

These adults who knew my secret, showed me what was going on at home wasn’t something I was meant to talk about: my problems were my problems and it was up to me to figure out how to deal with them. But in my fantasy world, they shook their head in marvel at me, telling me how brave and strong I was to have thought call the police. They sat beside me and told me my story was worth hearing and my hand was worth holding.

But though my fantasies helped, the real world responses of the adults I had told did have an impact. By looking away, unwilling to bear witness to my pain, I felt exposed. The story they didn’t want to hear now felt unspeakable; and by association I felt unspeakable too.

Unspeakable also meaning:

Repellent

Repulsive

Sickening

Contemptible

The quick way they had turned from my story, drove it deeper into hiding, and all of the unspeakable things I was not meant to share seeped into me, soaking my tissues, my organs, my bones until I could not tell where my stories ended and I began. I was repellent, repulsive, sickening, contemptible. That was what my Dad had tried to show me with his beatings. That was what the people who didn’t want to know anything about it confirmed.

It made me feel so lonely.

According to Carl Jung, “Loneliness does not come from having no people about one, but from being unable to communicate the things that seem important to oneself, or from holding certain views which others find inadmissible.” C.G. Jung

That was how I felt. Like my views were inadmissible.

The United Nation's Convention on the Rights of the Child says this: “Children who have been neglected or abused should receive special help to restore their self-respect.”

I did not receive this help, and neither do many other children. In fact, when people talk about children in traumatic situations, often the first word that gets bandied about is resilience. As if it is somehow easier for kids, whose bodies are still growing, whose neural networks are still forming, whose entire concept of the world is being created, as if it is easier for them to spring back from abuse.

People cling to the idea that kids adapt. And they are right. They do. They “adapt” by swallowing their feelings, thinking they don’t matter. They “adapt” by disassociating and shutting down. They “adapt” by developing a shield of anger that prevents anyone from getting close and hurting them again.

Children are just people. They are no different to you, except they are more naïve, more vulnerable and less able to fend for themselves. Like you, they expected their parents to help and protect them. That they have been treated brutally instead is as much a shock to them as it would be to you. To help them, the main question you need to ask yourself is:

How would I feel if it happened to me?

I think I would have liked someone to ask me if I was okay, so I could have told them that things were pretty hard.

I think I would have liked someone to take the time to try to understand my experience, and give me a safe place to vent my anger and frustration and confusion and sadness. I think it would have made me feel like I was entitled to have feelings of my own, and that it wasn’t only what was going on in the lives of the grown ups around me that mattered.

I think it would have made a difference to they way I understood the world if someone had told me that the way your parents treat you is not a representation of how much you are worth. And that just because your parent hits you doesn’t mean you deserve to be hit.

But then I would also have been wary. My whole life I had been let down by the adults who were meant to help me. As a child, even as an adult, trust was not something that came easily to me. If I had opened up to someone and they dismissed what I was saying, or tried to make light of what I was going through, it would have confirmed my opinion that I didn’t count.

I would also have been cautious because I would have wanted to protect Mum, the way I always had.

My Mum didn’t give me a huge amount in the way of engagement and attachment, but for much of my life she cooked my meals, washed and ironed my clothes, and packed my lunch for school. She let me hug her and she didn’t ever mean to hurt me. For that I loved her. Adored her. But that wasn’t enough to save her.

After Dad left, Mum plunged into despair with an abandon that made me think of those women who loaded rocks into their pockets before drowning themselves in a lake.

After a lifetime of other people making decisions for her, she was beyond terrified at being left as the sole adult-in-charge. I did what I could to not be a burden to her because I couldn’t bear to imagine her thinking of me as just another rock in her pocket.

But still she didn’t cope. By the time I was thirteen, she was mostly blind drunk or unconscious. I was scared that if somebody found out how bad her drinking was, us kids might have been sent into care. Which to my mind would have been ridiculous. By that age, I had done more looking after than I had ever received. I had “adapted” to my home environment.

Going to live in a stranger’s house, knowing they took me in out of the goodness of their hearts because they felt sorry for me, would have been a hundred times more awful than having a drunk Mum.

If I ever had a chance to speak to someone about what was going on at home, I would like to have some reassurance that what I said wouldn’t mean they could take me away from my Mum. And that if I did say anything about her, she wouldn’t get into trouble for it.

Besides if we go back to the United Nation's Convention on the Rights of the Child, “Children have the right to have their views heard, considered and taken seriously in a way that is appropriate given age and ability, especially when decisions are being made that affect them.”

I would have wanted people to know that I was basically doing okay. My situation might not have been ideal, but I was doing well at school, eating, cleaning my clothes. I didn’t need to be removed. It just might have been nice to know there was someone I could talk to sometimes so I didn’t have to feel so alone.

But that wasn’t the experience I had. Once it seemed obvious to me that no adults were interested in what was going on in my home, I didn’t bother telling anyone else. When I was fifteen, and Mum said she was going to move to Brisbane to get help with her drinking, I told her I wasn’t going with her.

I was about to enter my final year of high school. I was sure all the hard work I had put in would be wasted if I had to re-orient myself to a new curriculum in a different school while at the same time acting as Mum’s live-in counselor as she dealt with detoxing.

When I told her I was going to stay in Rockhampton, I had all my arguments in place, ready to defend my decision, but as soon as we worked out the practicalities of how I could pay my way, Mum didn’t really put up a fight.

Beginning my final year of high school living without any parents, I felt sure I was going to be discovered somehow, but gradually it dawned on me, no one was paying attention. I had been forging Mum’s signature on school notes for years. I had always ridden my bike to after-school activities. I was working and getting Austudy so I could pay for most things I needed. How would they even notice?

I finished year twelve on my own, then moved to Brisbane to study biochemistry at university. It wasn’t until I neared the end of my degree that the stress of doing everything alone for so long began catching up with me.

Like soil that comes to repel water when it has been dry for too long, preventing moisture seeping into the very place it is needed, I had learned to repel anything that even approached nurturing. I hung around people who didn’t want to go deep so I didn’t have to go near the vulnerable places inside myself. I shied away anyone who had too much kindness in their eyes, because I knew they could unravel me.

And unraveling was the last thing I wanted. I was finally living in a house of my own choosing. I was doing well at university. It felt like my life was just beginning. I didn’t want to think about everything that had happened in my childhood. I just wanted to be normal.

I tried to do same thing my Dad had been advised to do after he returned home from the Vietnam War: to go about my life as if nothing had happened. Like him, I kept the door on my experiences locked. But much as I wanted to contain it, my past had a way of springing back to life when I least expected it – sudden tsunamis of rage, crushing bouts of shame, aches of sadness so deep it felt my body would crack in two. All of the things I hadn’t dealt with had gone nowhere, and my body wouldn’t let me forget it.

I know many people who had childhoods like mine have managed to not only close the door on the past, but weld it shut, pour concrete over the whole lot and tell themselves they have moved on. I don’t know why I couldn’t do that. Somehow, the voice of the little girl that I had been was too loud. She wouldn’t let me keep ignoring her.

One day I called Lifeline, and shared some of my story. It was the first time someone had said, “You have been through a lot, it’s no wonder you feel overwhelmed.” They said I could call back any time, but I didn’t. The phone call made me feel so much better, like a weight had been lifted. I told myself that enough was enough. The voice of my child had been heard. No point boo-hoo-ing about the past forever.

Then in my early twenties, the drive and determination that had got me through my childhood started to wane. I found myself sobbing every time I had a few drinks. I saw a counselor a few times, trying to get her to help me leave the past in the past.

Then when I was twenty-four, Dad died of melanoma cancer.

A year after that, Mum was found at a train station, her mind stuck in a loop. She kept repeating that she needed to catch a train but couldn’t find her luggage. She couldn’t remember her name. At hospital she was diagnosed with alcoholic dementia.

When she finally remembered who she was, they contacted my sister, who contacted me. I flew up from Melbourne to see Mum. She recognised me, but after a quick hello her eyes darted anxiously around the room as if trying to find the suitcases she had left behind. Whenever she managed to stop herself from pacing, she slumped, slack-mouthed. I shrank when I saw her nails – long and ragged, stained with nicotine –the nails of a homeless person.

Those nails broke my heart. I was in relatively regular phone contact with Mum. Often it didn’t make a huge amount of sense, but I though she was just drunk. I could not believe she could be in a state like this.

‘Her problem isn’t medical. She can’t stay at the hospital.’ The nursing staff told us.

‘Where is she going from here?’ we asked.

‘She’ll have to go home with one of you.’ They looked at my sister, my brother and me.

I was shocked. We all loved Mum. But we were in our twenties. Working. Trying to escape our past and make a life for ourselves. Did they really expect us to become full-time carers for someone with dementia? Our wants and needs sidelined while our parent’s took centre stage again? When would it be our turn?

I told Kerstin there was no way I was doing it. She said she wasn’t either and they soon found a place for Mum in a care facility.

The ongoing cost of being raised by damaged parents

When the roles of who is meant to care for whom have been reversed for your whole life that doesn’t stop when you reach 18 and are officially thought of us an adult. You go on giving to the people you love and they go on receiving.

While many other people receive support from their families, children living with abuse and neglect are often the ones doing the supporting. They support their parents as children, and they support them when they are adults, often both emotionally and financially.

But that is not the only price they pay.

I spent my entire twenties working part-time. A quarter of my salary each week spent roaming from kinesiologist to healer to therapist. A lot of my free time was spent crying, not seeing people because I couldn’t bear to have them look at me.

Imagine if all the energy and time I spent just trying to feel like a worthwhile human had been directed to some other output. I might have cured cancer or painted a masterpiece.

What about the people who don’t go into therapy and who instead turn to alcohol and drugs to numb the pain? How many of those will de-rail their lives, end up in jail? Did you know it costs $90,000 each year to have one person in jail? What if some of that money had been devoted to supporting and intervening when these people were children, might that have made a difference to the way their lives ended up?

Or what about those who repeat the pattern of violence they experienced, creating a whole new generation of people grappling with violent childhoods of their own?

Surely if these ongoing costs to society were given the consideration they merit, the support of children from abusive homes would be considered a national priority.

***

In my mid-twenties, after Dad’s death and Mum’s dementia, I decided it was time to bite the bullet and surrender to the fact that I had been dealing with too much for too long alone.

I started weekly psychotherapy. My therapist, Mary, changed my life. For the first time I experienced what it was like to be in a genuinely nurturing relationship with someone parent-like. Somebody who held the space for me, made me feel safe enough that I didn’t always have to be strong. Week after week, month after month, year after year, she listened to my story. Finally I was not alone. Finally I had been heard.

Our work together was deep and profound, and for the first time I trusted someone enough to dig past a million “I’m okays,” to the lifetime of heartbreak I had never dealt with.

I had studied psychotherapy for a year, I had read a lot of Jung. I had read his words: “There is no coming to consciousness without pain.”

I thought I knew what was coming. But boy it hurt more than I thought it would.

It hurt more than I ever remembered it hurting the first time around, because finally I wasn’t acting like it didn’t matter. I fought back monsters for the insights I gained, waded through festering swamps to recover ground I thought I’d lost, but finally, on a river of tears, in a canoe I made myself, I found my way to the child I had been, took her in my arms and gave her the hugs she didn’t think she deserved.

Once we had spent time living with the darkness, Mary also showed me that there was also a whole lot of light I hadn’t been acknowledging either. I took more of Carl Jung’s words to heart: “I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.”

I came to see the hypervigilance of living with a father who might turn violent at any moment had turned my body into highly tuned instrument. Without much conscious effort I picked up on small details that let me see the things that people really meant when they spoke. This felt to me like a secret weapon.

I also came to understand that my ability to disassociate was the bedrock of my creativity. Spending my entire life acting the way everyone else needed me to had honed my skills as an actor. Creating alternative realities in my head so often meant writing came as naturally to me as breathing.

My childhood had taught me to be brave and strong and independent. Sharing my story had shown me I didn’t have to feel so alone.

So after all of that hard work, I thought, “Brilliant. The past is dealt with. Time to move on.” And in many ways I did move on. I earned my money as a copywriter, a job I loved. I married a kind and gentle man. I had first one child, and then another. Both were the loves of my life.

Though I found parenting pretty full-on, I thought I was doing okay at it. Then, when my youngest child was two, he went through a phase where every tiny frustration made him lash out, mostly at me. He went through biting, head-butting, scratching, punching; but the worst for me was the face slapping.

If he fell down, was unable to remove the lid off a bottle, or I didn’t understand what he was trying to say, he would walk up and slap me across my cheek as hard as he could.

The familiarity of that sting triggered old neuronal pathways that derailed my adult self. All knowledge that my son was exhibiting normal two-year-old behaviour was forgotten as I tumbled backwards inside my skin, free falling to the bottom of a long dark well. Looking up through the eyes of my younger self, my son was not my son, he was my father. I was doing nothing wrong and I had been hit. My hand itched to slap back.

Luckily I understood that though I felt violated, as the parent I was the one with the real power. I would not let myself abuse it.

Still, my voice was more a roar than a calm instruction as I told him, “No! It is not okay to hit. Be gentle with your hands!”

It had been over twenty-five years since Dad laid a hand on me. Yet some days it still felt like my past dragged behind me like a sack of drowned kittens. I was utterly bored by the tear-soaked drama of it all.

This, despite the thousands of hours I had spent trying to “get over it.” This despite the thousands upon thousands of dollars I had spent in the effort to move on.

The problem is that when your trauma is your childhood, your own children can trigger you. Their behavior can evoke a memory that floods your body with cortisol and adrenaline making your heart pound and your hands shake. You know you need to calm down. But you can’t just leave the house and go for a walk. You have to keep looking after your child. You manage to do it, though your body is still buzzing. Then, a short while later, another memory is triggered, enough to release another flood of chemicals that wash through your body and compound its already agitated state. You can feel how wound up you are getting, but what are you meant to do? You are home alone with your child. Because of the kind of family you grew up in, you have no family to support you.

This is one of the impacts of childhood trauma that you can’t think your way out of: the way your body remembers it.

***

I have always believed in the power of education. As Maimonides said, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

Over the decades, I have read hundreds of psychology and self-help books, many of which opened up my mind up to the ways I could make real changes in my life so my childhood didn’t have to define me.

Many times I have wondered why every child is not taught this. Why is something like algebra given so much time and attention when most people use it so rarely, yet our psychological world, which impacts every interaction we have, every single day, is ignored?

Because children’s brains are still developing, and their image of themselves is still forming, there is so much potential for the early help they receive to have real and lasting impacts on their growth and development. Why are we not arming children who are struggling against the disadvantage of living with violence, abuse and neglect with tools that might level the playing field a bit?

What if we didn’t shy away from their difficult stories? What if we heard them, or shared stories of our own so they might know they were not alone in their experience?

What if we taught them about the choices they have, and that their feelings matter? Or that there are things they can do to make positive changes in themselves? That all is not hopeless and lost.

What if they were taught that some behaviours are acceptable and some are not, and just because you are a child and someone is your parent doesn’t mean it is okay for them to hit you?

What if they were shown that there are more choices in the world than growing up to be your father or your mother?

What if we taught them tangible skills so they could learn to be more empathetic, compassionate and caring, not just to others, but to themselves?

What if they knew about the free services available to help them if things aren’t going too well at home?

What if they understood that there is a gap between the way your body feels and your decision to act on it?

What if they were taught techniques for self-care and how to reduce their stress in healthy ways. The EFT tapping technique. Breathing exercises. Meditation. Drawing. Painting. Writing. Singing.

If I had received this information was I was younger, I could have started making changes in my life sooner. We might not be able to help the circumstances a child is born into, but we can show them that they are not alone and support them in finding new ways to respond to their experience. We can teach them that there are things they can do to look after themselves, because they deserve to be looked after and treated with kindness.

Luckily for me, the time when I had to endure the constant threat of attack is long gone. But it is not gone for many kids. All over Australia children are nursing broken bones, broken hearts and broken promises because the people they rely on for love and care instead made them feel like they were worth nothing. It is for those children that I speak today.

In many ways, having written my book has completed my need to tell my story. But I will keep telling it because there are other people out there who have not been heard. And I want them to know they are not alone. And that is okay for them to talk about all they have been through.

As Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi says:

Every single child matters.

Every single childhood matters

Every child’s story deserves to be heard.

Thank you

Purchase Ruth Clare's 'Enemy: A daughter's story of how her father brought the Vietnam war home'