12 Ocrtober 1936, Salamanca Unversity, Spain

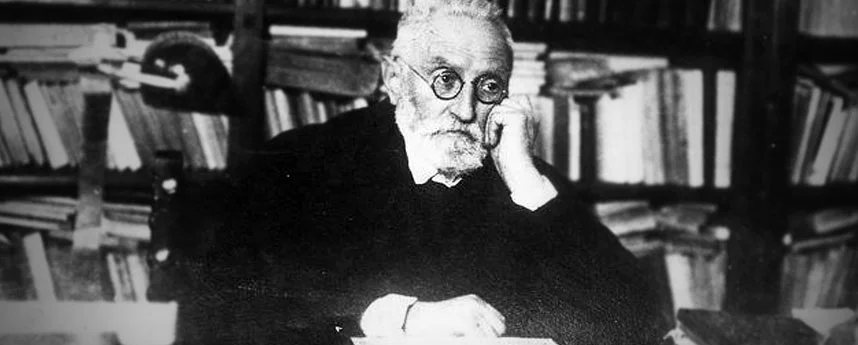

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo is one of Spain's most eminent novelists, poets and playwrights. He was rector of Salamanca University, and a professor in Greek. On the day of this speech, General Franco's chief advisor, General Millán Astray, a military hero with an eye patch and a missing arm, spoke from the audience's midst, shouting the paradoxical phrase, 'Viva la Muerte!” — Long Live Death! This was Unamuno's response.

All of you are hanging on my words. You all know me and are aware that I am unable to remain silent. I have not learned to do so in seventy-three years of my life. And now. I do not wish to learn it any more. At times, to be silent is to lie. For silence can be interpreted as acquiescence. I could not survive a divorce between my conscience and my word, always well-mated partners.

I will be brief. Truth is most true when naked, free of embellishments and verbiage. Let us waive the personal affront implied in the sudden outburst of vituperation against the Basques and Catalans in general by Professor Maldonado. I was myself, of course, born in Bilbao in the midst of the bombardments of the Second Carlist War. Later, I wedded myself to this city of Salamanca, which I love deeply, yet never forgetting my native town. The Bishop [here Unamuno indicated the quivering prelate sitting next to him], whether he likes it or not, is a Catalan from Barcelona.

I want, however, to comment on the speech — to give it that name — of General Millán Astray who is here among us.

[the general was sitting on the stage and had given a pro fascist speech moments before].

Just now, I heard a necrophilic and senseless cry, ‘Long live Death!’ To me it sounds the equivalent of ‘MUERA LA VIDA!’ — ‘To Death with Life!’ And I, who have spent my life shaping paradoxes that have aroused the uncomprehending anger of others, I must tell you, as an expert authority, that this outlandish paradox is repellent to me. Since it was proclaimed in homage to the last speaker, I can only explain it to myself by supposing that it was addressed to him, though in an excessively strange and tortuous form, as a testimonial to his being himself a symbol of death.

And now, another matter. General Millán Astray is a cripple. Let it be said without any slighting undertone. He is a war invalid. So was Cervantes. But extremes do not make the rule: they escape it. Unfortunately, there are all too many cripples in Spain now. And soon, there will be even more of them if God does not come to our aid. It pains me to think that General Millán Astray should dictate the pattern of mass psychology.

That would be appalling. A cripple who lacks the spiritual greatness of Cervantes — a man, not a superman, virile and complete, in spite of his mutilations — a cripple, I said, who lacks that loftiness of mind, is wont to seek ominous relief in causing mutilation around him.

General Millán Astray is not one of the select minds, even though he is unpopular, or rather, for that very reason. Because he is unpopular, General Millán Astray would like to create Spain anew — a negative creation — in his own image and likeness. And for that reason he wishes to see Spain crippled, as he unwittingly made clear.

At this General Millán Astray was unable to restrain himself any longer. ‘Death to intellectuals! Down with intelligence!’ ‘¡Mueran los intelectuales!’ [‘¡Abajo la inteligencia!’] he shouted. ‘Long live death!’ [‘¡Viva la Muerte!’]

This is the temple of intellect. And I am its high priest. It is you who are profaning its sacred precincts.

I have always, whatever the proverb may say, been a prophet in my own land. You will win, but you will not convince. You will win, because you possess more than enough brute force, but you will not convince, because to convince means to persuade. And in order to persuade you would need what you lack — reason and right in the struggle. I consider it futile to exhort you to think of Spain. I have finished.

Orders were initially made to kill the rector for making the speech, but this was commuted to house arrest when the regime decided the execution would create an international incident, and injure its nascent “National Movement of Salvation”. Unamuno died under house arrest on the last day of 1936, two months after the speech.