8 December 2014, Australia

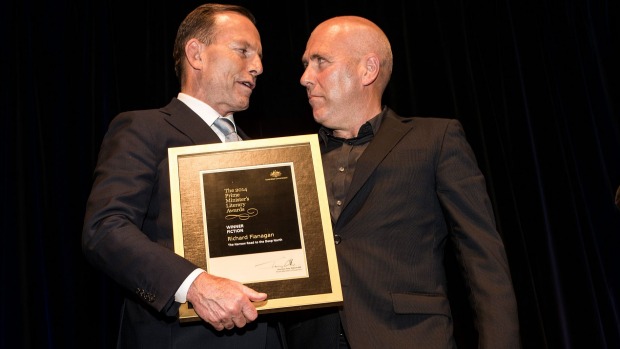

Richard Flanagan's novel 'The Narrow Road to the Deep North' was joint winner of the fiction prize with Steven Carroll's 'A World of Other People'.

I thank the judges and the Prime Minister for this award.

I commend the Prime Minister for continuing with these prizes at a time of austerity. And I commend the Prime Minister for lending the event here tonight the authority of his office simply by being here. These are not small things, but large symbols of what a civilised society should be—one in which culture is not understood as an economic utility, or a political embarrassment, but as the necessary nub of who we are.

As the ideas of our country grow vaporous, as some young Australians find more in common with murderous fantasies in far off lands than the society in which they live, we need that culture more than ever to remind us of all that we share, for our security ever lies not in our capacity to exclude some, but to include all.

It is often said that politics shouldn't be about symbols, but acts. But in the end acts are symbols, and symbols are powerful acts. We find in symbols our meaning to live, and that meaning can be wicked, or it can be a source of hope. We choose what we wish to celebrate for reasons bad or good: a beheading—or a book.

This book would not be what it is without my publishing company, Random House, nor my publisher of near twenty years, an editor of genius, Ms Nikki Christer, and I thank her from the bottom of my heart.

For penurious writers—who in Australia on average earn according to the Australia Council less than $11,000 a year—a prize such as this—one of the world's richest— means one very simple thing: that they can continue to write for a few more years without fear of poverty. In any past year I would have welcomed this money to help me in the struggle to write, and in any future year—were I ever again to know such honour as this, I will, with delight, use the money for a few celebratory drinks and the rest to keep writing.

This year though I have been—as you may have heard—unexpectedly lucky. For all that, I am not a wealthy man, and though I could put this prize money into my mortgage, I intend to use it differently.

And there are two reasons for this. Let me explain them.

The origins of this novel lie in my late father's experience as a Japanese POW. The lesson that my father took from the POW camps and imparted to me was that the measure of any civilised society was its willingness to look after its weakest. In the camps the officers were levied, their money used to buy food and medicines for the sick.

Money is like shit, my father used say. Pile it up and it stinks. Spread it around and you can grow things.

My book only exists because in that hellish place long ago the strong helped the weak. These were concrete acts that became for me, growing up, symbols of what a good society might be.

Of what our Australia is.

My other reason is this: if me standing here tonight means anything it is the power of literacy to change lives. The difference between my illiterate grandparents and me is two generations of free state education and literacy.

Words, my father told me, were the first beautiful things he ever knew.

I intend to donate this $40,000 to the Indigenous Literacy Foundation for its work with indigenous children, helping them to read. I hope it might perhaps grow a few things.

My mortgage will go on as mortgages do, but if one of those books helps a few children to advance beyond the most basic literacy to one that is liberating, then I will consider the money better spent.

And if just one of those children in turn becomes a writer, if just one brings to Australia and to the world an idea of the universe that arises out of that glorious lineage of sixty thousand years of Australian civilisation, then I will think this prize has rewarded not just me, but us all. And for that we will all owe this prize an immense debt of gratitude.

Thank you.

Flanagan's book also won the Man Booker Prize. Buy it here.