January 2017, Rowville Golf Club, Melbourne, Australia

If I was to tell you today that my father was a great man I suspect – in fact I’m certain – he would be uncomfortable with that. Apart from his natural humility, I think he would suggest greatness is a term that ought be reserved for those who’ve saved thousands of lives, or changed the course of history in some important field of human endeavour.

So today, of all days, I guess I should defer to my father's view. I hope Dad that makes up, at least to some extent, for all of those many occasions in the past when I didn’t.

But if the next best thing to being a great man is being a good man, and if the measure of a good man is his ability to positively influence the overwhelming majority of the people he comes into contact with throughout the course of his life, then I feel very confident in saying that my father was a VERY good man.

How do we do that? How do we have a positive influence on those we come into contact with? What was it that Dad did to qualify him so clearly in my mind as a very good man.

One of the most significant things was his ability to make the people around him feel that they were important; that their lives and their opinions mattered.

You’ve already heard from my sister Diedre about how Dad was able to do this with his own family. I’d just add one further recollection to what has been said to you so far on that subject. My father was a very gifted storyteller. And what a difference it makes as a child to have stories told to you that don’t come from a book, that have never been told to anyone else before, and that are therefore accompanied by the pictures we create in our own imaginations. My father's most popular stories, told to his children and grandchildren over many decades, centred around the characters of Woggie the Snoggie, Wiggy the baby Snoggie, their faithful off‑sider Flip Flap, and the unspeakably evil Gremlin Goblin. Not only were these characters vivid, and wonderfully conceived, but whenever a "Woggie the Snoggie" story was told, the listener would himself or herself be a character in it, and that story would be custom-tailored to their age and interests.

What better way for a sports-mad young boy to fall asleep than with visions of having been selected from obscurity to represent Australia at the SCG, only to hit the winning runs in the deciding Ashes Test match, or to be plucked from the crowd during the ¾ time huddle to kick the match-winning goal for the Melbourne Demons at the MCG in the Grand Final.

Nothing was improbable, let alone impossible, when Dad was telling bedtime stories.

And my father's ability to make people feel important wasn’t confined to members of his own family. So many of you here wrote and spoke to us of this very quality in the days following his death, and about how good he was at giving you his undivided attention, and taking a genuine interest in your lives.

At the peak of his powers my father knew a lot about a lot of things. And if you were prepared to listen, he was more than willing to give you an extract from that vast library of accumulated knowledge and wisdom.

That said, conversation with Dad was never a one-way street.

Unless of course you were a teenager who'd drunk considerably more than was good for him. But more about that later

Dad was always interested to hear what the other person had to say, and to find out what was important in their life.

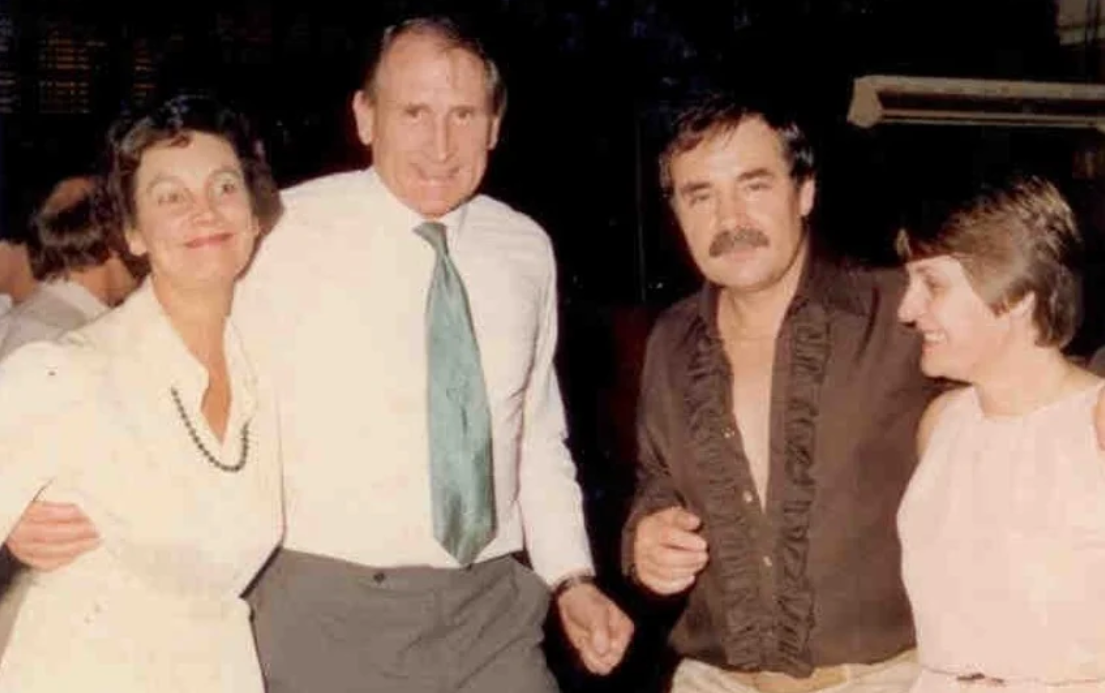

The photo you see here emphasises this point. Dad worked for many years in an office building in Walker St, North Sydney. As my brother Ian has told you, he was the Managing Director of an international company whose Australian management team were based in those offices. The man with the moustache, whose name was Arthur, was the car parking attendant in the building where my father worked. When Arthur got married he invited my Dad, and my Mum, to attend his wedding. Was the wedding full of business people who worked in that office building? Almost certainly not. Did Arthur invite Dad out of some sense of gratitude towards his biggest tipper? Definitely not. Arthur asked Dad to share one of the most important events in his life because Dad had made a real and genuine connection with a man with whom, looking from the outside, you might think he had absolutely nothing in common.

But Dad didn’t care who you were, how much money you had, what school you went to, or what you did for a living. He didn’t care whether you were male or female, Australian or foreign-born, straight or gay, sporty, arty or neither.

He would listen to you, and treat you with the respect you deserved, regardless of any of those things.

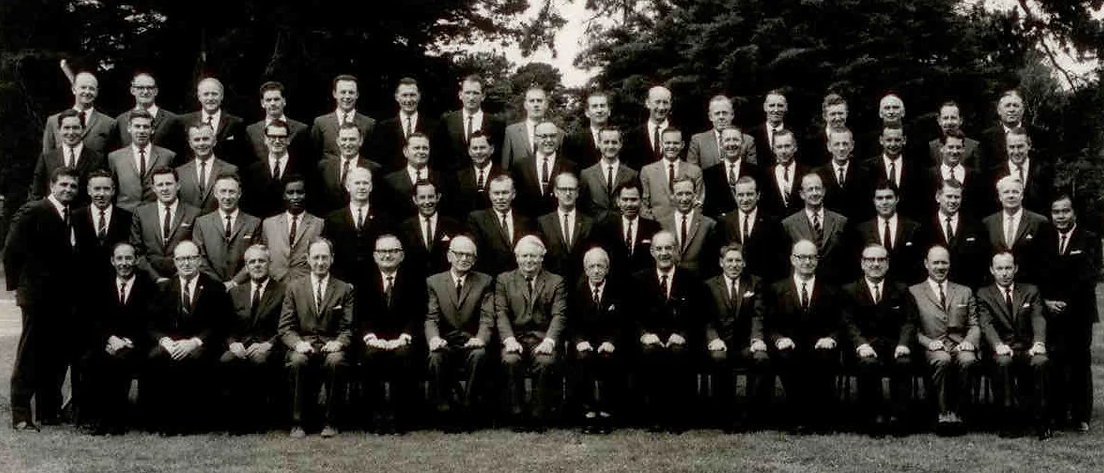

This is a photo of the attendees at a Senior Management course conducted at The Australian Administrative Staff College just outside of Melbourne in the latter part of 1968. Most of the 55 participants were Australians, but there were some overseas delegates. Towards the end of the course Dad invited one of those international visitors to our house to meet our family, and for a day’s outing to the Healesville Sanctuary, a couple of hours drive out of Melbourne. That man’s name was Frank Nkhoma. Frank worked for the Zambian Government, and you can see him in the 2nd row from the front, 5th from the left.

I was 5½ years old at the time, and Frank looked different to anyone I’d ever seen. Indeed I suspect most of the attendees at that Management Course had never met an African man before. Even though Frank and Dad were not in the same group at the Staff College they became friends. Looking back, it is not hard to see why. Frank radiated an extraordinarily warm and generous spirit. When he smiled, and said to me in that deep charismatic voice of his “You are a very good reader Geoffrey” I felt ten feet tall. I still occasionally try to emulate that voice of Frank’s today when praising my own boys. I have never forgotten him, and I hope I never will. Dad extending the hand of friendship to Frank, and Frank extending the hand of friendship to me: I now realise these were life–defining events for that 5-year old boy.

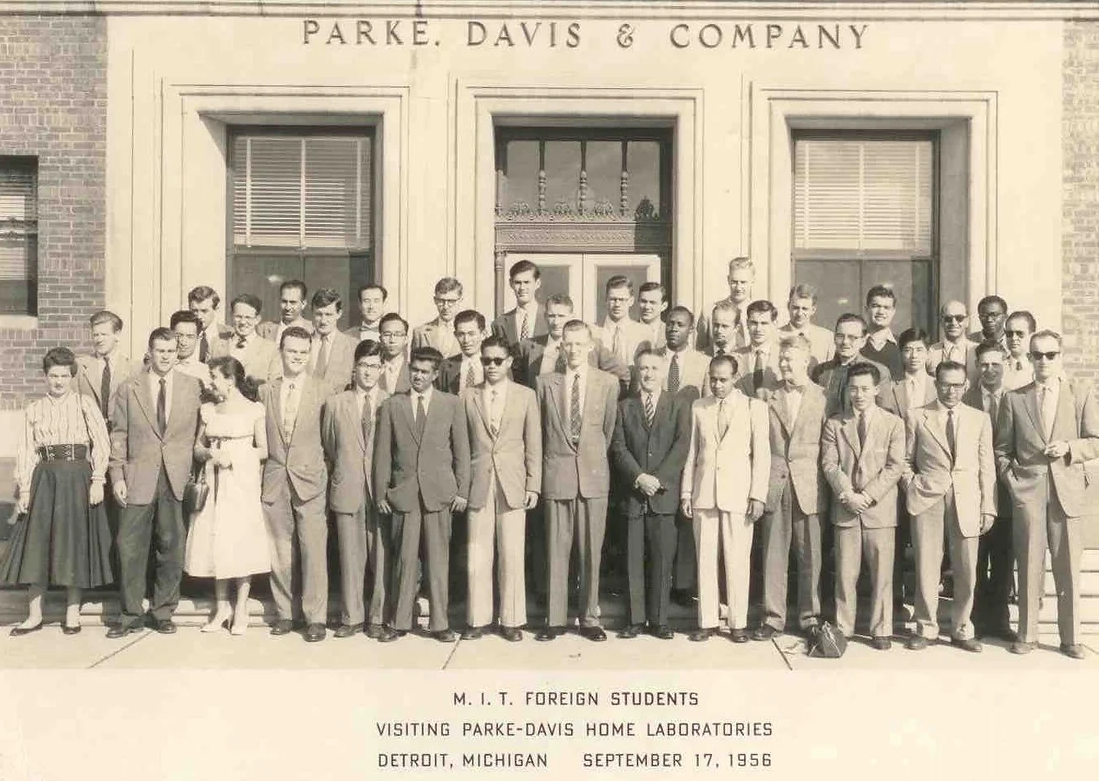

Not too many years ago I asked my father about Frank. He confessed that they had not kept in contact after Frank returned to Zambia, although Dad had written a letter to him which went unanswered. We didn’t have Facebook or email back then of course, and I suspect the mail system in Zambia may have been less than ideal at that time. But as we talked about Frank, and I asked Dad, through an adult’s eyes, about their friendship, he confessed to me that part of the reason he was so determined to make Frank feel welcome in this country, and into his home, was an experience my father had had some years before when he attended MIT in the United States as part of the Foreign Student Summer Project he had been accepted into after receiving the Fulbright Scholarship Ian mentioned earlier.

The Official Report from that Summer Project confirms there were 67 participants from 35 different countries – countries that, remarkably, included India and Pakistan, Iran and Iraq, Israel and Egypt, South Africa and Kenya, Greece and Turkey, as well as Japan, Germany, Italy, France, the UK, and many others.

And this was in 1956, when the state of diplomatic relations between many of these nations was tenuous to say the least.

During the course of the Project the delegates, all of whom were engineers and/or scientists, were taken on visits to factories and laboratories in various parts of the US. On such visits they would travel by bus. On one such occasion the buses transporting the group stopped at a roadside diner to have lunch. However the staff at the diner refused to serve the Asian and African delegates. They didn’t ask the group to leave, they just told those in charge that they would not be serving those members of the group who were not Caucasian.

There was nothing preventing the majority of white-skinned delegates from eating, or getting something to drink. But they chose not to be fed, or watered. Instead, in what was an extraordinary show of solidarity amongst people from all corners of the globe, people of different colours, different cultures, different religions and backgrounds, the entire group rose from their seats and they left the diner together.

Just think for a second about seeing that moment as a scene in a movie – what an incredibly powerful image that would make. And what an inspiring message that group sent that day to those who had allowed prejudice to overshadow their humanity.

Now I don’t want to suggest for a second that my father was solely, or even principally responsible for orchestrating that walk-out all those years ago. But what I do know with certainty is that he wouldn’t have hesitated for a second to be a part of it. Because that’s the kind of man he was.

Which leads me to the second significant way that a good man can positively influence those around him – and that is through the example he sets.

You’ve seen lots of photos today, and you’re going to see plenty more. In many of those photos you’ll see my father holding a drink of some kind, often a glass of wine. He loved his wine – indeed he bottled wine purchased in bulk direct from the vineyard many, many times throughout the second half of his life. He also brewed his own beer, somewhat less successfully, on a number of occasions. So alcohol was always a part of our lives as a family. And yet in the 50 years that I am able to recall I don’t believe I ever saw my father adversely affected by drink.

Not once.

Which is why the conversation I am going to tell you about now resonated so strongly with me at the time.

It's a Sunday morning. I am 17 years of age, and I have awoken at about 7.30am to discover that my bed has not just been slept in, but it has been vomited in. Upon surveying the scene I ascertain there is a conspicuous absence of other likely perpetrators. Albeit gingerly, I determine to accept responsibility. I gather the remnants of my last meal in a bundle of bed linen, and head for the washing machine, confident that I will be able to dispose of the unsavoury evidence before my parents appear.

Unfortunately my mother has chosen this Sunday, of all Sundays, to rise earlier than usual to collect and read the newspaper. She asks me, as I pass her en route to the laundry, what is in my knapsack; which I now notice is dripping ever so slightly onto the kitchen floor. I confess my sins. Mum offers to clean the sheets for me. As a parent of a son in his late teens I now understand why she did that. I wonder however, as she takes my parcel from me, whether she will feel inclined keep this little secret between us.

She does not.

Later that day Dad comes a calling to my room, where I am feigning studious dedication whilst in truth simply nursing a ferocious hangover.

His first serve is moderately paced, but it has some spin on it.

“I hear you had a bit of a problem last night” he says.

I return the serve gently into mid-court.

“Yes” I reply.

Dad places his approach shot deep into my backhand corner.

“Is this the first time this has happened?” he asks.

I am unsure whether he means “Is this the first time you have vomited from drinking too much?”, or “Is this the first time you have vomited in your bed from drinking too much?”

I choose to answer the second question.

“Yes” I say truthfully.

Dad is now at the net, ready to put away the easy volley.

“Right” he says. “Well – the first time it happens that’s an experience. The second time it happens you’re a fool. And the third time – well, if it happens a third time you’ve got a problem”.

It is now clear to me that I have answered the second question, but that Dad was asking the first one. I do some quick calculations in my head. They lead me to the inescapable conclusion that I am a full-fledged alcoholic.

It is game, set and match for me it seems.

Thankfully the passage of time, and a relatively small number of subsequent indiscretions, have allowed me to re-calibrate that initial assessment. But the point is that what Dad said had such an impact upon me because he practiced what he preached. Whatever the issue, he never asked more of us in our lives than he demonstrated in his own.

And although I didn’t appreciate it at the time, what I now realise he was doing was giving me a road map to follow if I wanted to be a good man too.

Now it’s safe to say there have been many times I left that road map in the glovebox. But at the times in my life when I’ve been forced to admit that I am well and truly lost, Dad’s road map has been there for me to refer to. And I’m sure I will refer to it many more times in the years ahead.

There are a couple of other stories I’d like to briefly share that will hopefully reinforce what I have said about the kind of man my father was.

When I was 10 years old Dad put his hand up to coach my team at the Lindfield Cricket Club. We were a rag-tag bunch, without much idea, at least half of us a year too young to be playing in the Under 12 competition. But by season’s end, as much to our own amazement as anyone else’s, we found ourselves semi-finalists. Dad was a big part of that. In his team no-one was more important than anyone else. Everyone was entitled to an opportunity. Those of you who are my age or older will remember that was not the way things were back then. In those days the talented kids did all the batting and bowling, and the rest made up the numbers. But Dad was ahead of his time.

We had a wonderful season. I remember still Dad piling the entire team - yes, the whole 11 of us - into his Ford Fairlane at the end of the last game before Christmas, and taking us down to the local milk bar so he could buy us all an ice cream. If we'd have played the All Blacks that afternoon we'd have had a fair crack at winning back the Bledisloe I reckon. Dad knew full well that if you don't have a team of champions, you're gonna need to build a champion team.

But of course talking the talk is just one part of the equation isn't it?

When I was 17 my father and I played cricket together with the Mosman Vets. Our team sometimes included four players with first-class cricket experience - Dad being one of them, albeit more than 50 years of age by then – along with Allan Border’s future father-in-law. One of my fondest memories from that time is a match in which Dad bowled the final over to the Nawab of Pataudi – a former captain of India with six Test centuries to his credit – with the batting side needing a run a ball to win. As wicketkeeper I had the best seat in the house, watching the two aging champions going toe to toe, with the game coming down to the last ball, and ending in bizarre circumstances. Although on the losing side, Dad shared a beer and a laugh with his opponent afterwards. Like the Nawab, I came away with even greater respect for Dad as a cricketer, and as a man, that afternoon.

When I was about 19 I suffered my first flat tyre. Now I know many of you may find this hard to believe, but I was not always as handy as I am today. When I called Dad at about 1.45am that particular night to ask him for help, there was not a moment of hesitation. I wonder now if he realised when he took the call what a fantastic bonding experience that episode would prove to be – the two of us tripping over one another in the dark on Lane Cove Road, roughly where it now joins the M2. As we sat on the kerb, about 3am by this stage, with the spare tyre securely in place, I remember finally expressing sincere gratitude to my father ‑ for probably the first time during my teenage years, which by then were nearly over.

Dad and I had quite a few things in common. We were both the youngest of four children. In each case our oldest sibling was born in England, 10 years and 2 months before we were born in Melbourne. The siblings closest to us in age – Denis in Dad’s case, Diedre for me ‑ were roughly 5½ years older than us. At his full height Dad was 6 feet 1½ inches, virtually identical to my 187 cm. Dad’s playing weight of 14 stone, which equates to about 89 kilograms, was almost exactly the same as my own. Those happy coincidences have allowed me to wear one of Dad’s suits today, which I am very proud to do. I think it’s also fair to say we were both accident-prone, which goes some way to explaining how I managed to split a substantial hole in the seam of Dad's suit pants just minutes before entering this room today.

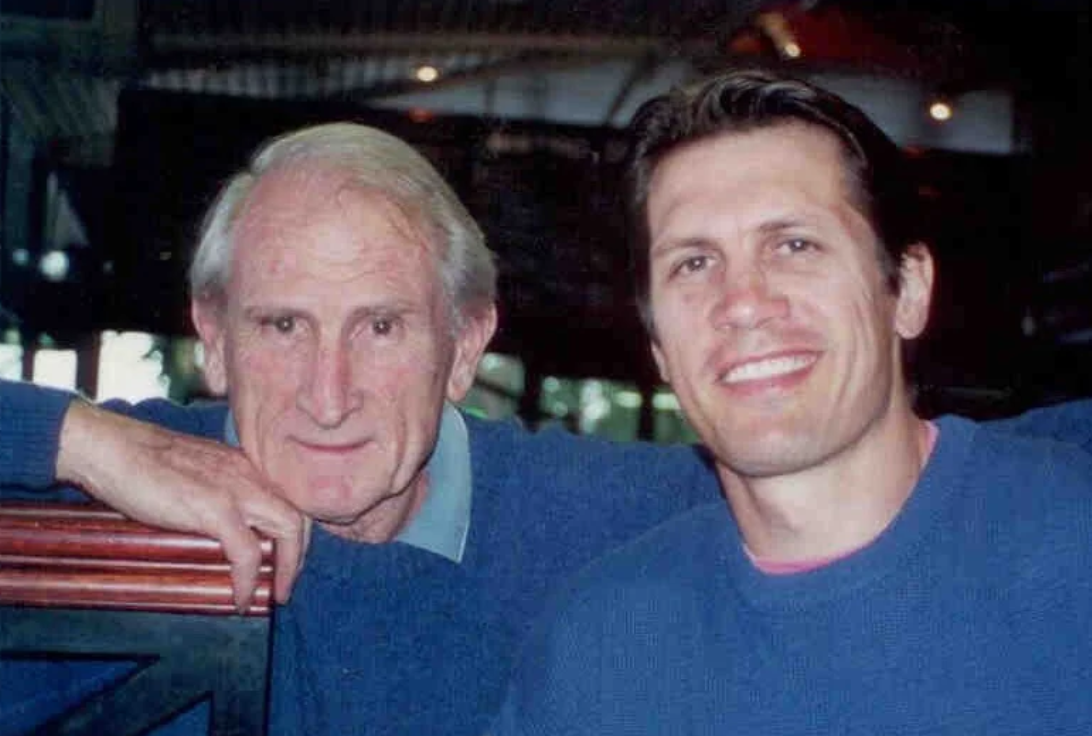

Dad and I both married strong, beautiful women who would prove to be our life-long partners and best friends. We both became a father for the final time at the age of 34 years and 3 months. We both appeared on TV quiz shows – twice each. We both saved our very worst golf for those occasions when we played together. We both loved cricket, so much so that we played it into our 50s. And we both had the good fortune to play that wonderful game with our sons – something that has given us immense pleasure.

Over the years, and especially the last three years, Dad and I spoke long and often about each others’ lives. I told him many times in different ways what he meant to me and, right up to the last time I saw him, his pleasure at having me visit him was wholehearted and unreserved. The knowledge that there was nothing left unsaid between us is, as you can imagine, of enormous importance to me now.

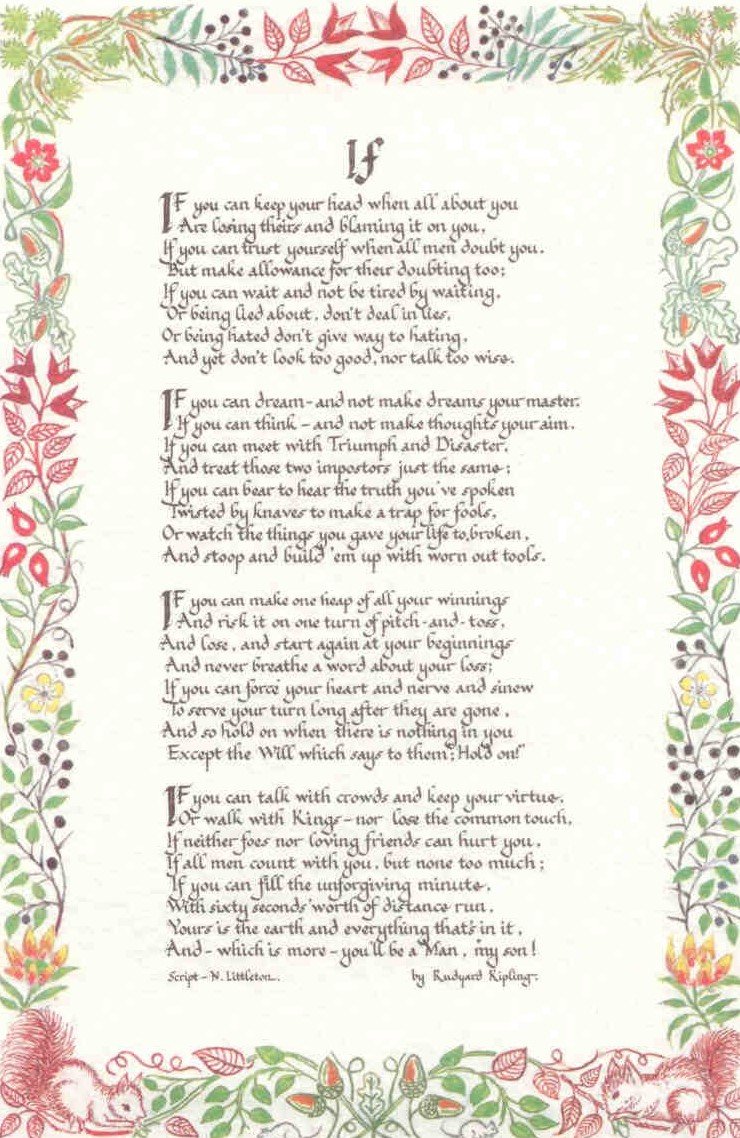

One of my father's favourite pieces of verse is a poem called If, by Rudyard Kipling. Having re‑read the poem recently, I understand why Dad rated it so highly. It is all about what it takes to be a good man.

Much as I like Kipling's version, it was not written for my father, or about him. So today, as a final tribute to you Dad, I would like to read an amended version of If; a version composed especially for you.

If you can keep your hair when all about you are losing theirs, and blaming it on stress;

If you can justify your Scrabble word when all men doubt you, and so achieve a triple letter score for your X;

If you can keep off weight without the need for dieting, and confess your age without the need for lies;

If you can just be envied without ever being hated, despite always looking good, and always talking wise;

If you can paint your dreams – and paint them like a master ‑ and still, with all your gifts, avoid the vanities of fame;

If you can meet with a Nawab, or with a Collingwood supporter, and treat those two extremes of humankind one and the same;

If you can bear to see the well-placed, kicking serve that you’ve delivered returned between the tramlines past your partner at the net;

Or watch the two-foot putt you need to end the match all square slide past the hole without a sign of petulant regret;

If you can, with either bat or ball in hand, with equal sureness, make a yorker of what seemed to all and sundry a full toss;

And if indeed, in any game, no matter what the stakes are, you can lose with grace and never make excuses for your loss;

If of the ones you love you ask no more than you bestow, and in their times of need provide a sympathetic ear;

If loyalty and integrity mean more to you than wealth, and compassion and encouragement are words that hold no fear;

If you have lived a life that’s both constructive and creative; if all this has been your oyster, and if you have glimpsed its pearl;

If when you speak your mind you know that those who hear you listen, you can be sure your time has left its impact on this world;

For more than four score years Dad you led us by example, your guidance and your love has made us stronger, every one;

And if I can be half the man you were while you were with us, then I hope you’ll be as proud a Dad as I am proud a son.