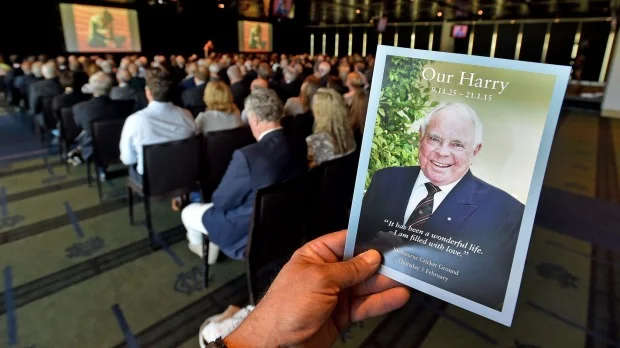

5 February, 2015, Melbourne Cricket Ground

I shouldn’t say this . . . but I can’t help thinking that Harry would see today as a missed opportunity.

Harry loved a lunch, as many of us here today know.

And at this time – around two o’clock – he’d be calling for a third bottle of wine. And he’d be telling people -- usually John Fitzgerald -- not to interrupt him while he told a short anecdote that would only take another twenty or thirty minutes.

And, if it happened to be a large gathering -- and Harry’s lunches usually were -- he’d eventually make a formal speech and go around the room, singling out people for praise and reminding them of something they wrote in 1953.

You tried to avoid eye contact, hoping Harry wouldn’t see you – but he always did.

And Harry not only loved a lunch. He loved this place, this stadium that once had a red-brick cinder track.

So what an opportunity missed today.

The MCG: he could have picked out someone he knew in the Ponsford Stand and called him ‘old bloke’.

What an opportunity missed. All these people, all of us his friends and more than that his admirers . . . people who owe him simply because of what he was and what he taught us by example.

I’m so old I first met Harry fifty-four years ago. He was assistant editor of the Sun News-Pictorial and I was a first-year cadet, wide-eyed and clueless.

But I felt I had known him long before then. As a kid growing up in the bush I used to read his stuff in The Sun.

This was the era of Dave Sands and Vic Patrick in the boxing rings, and of Betty Cuthbert, John Landy and Dawn Fraser at the Melbourne Olympics.

And even as a teenager I sensed there was something special about Harry’s work. I couldn’t identify what it was then. It was just a voice inside me saying: ‘This bloke’s different’.

His storytelling just flowed, clear and purling like a mountain creek.

Here was someone who seemed to live in a different place to most other journalists. There was a relaxed quality to his prose – no clichés, no showing off, no agenda. He led you along by the hand. He was the master of the anecdote that widened out into the bigger story.

Here was someone who obviously crafted every word, every sentence, someone who lived in this exotic halfway house between journalism and literature.

And you also felt that here was a generous spirit. Harry could scold in print without being mean.

And when I eventually met Harry in the flesh at The Sun he was exactly the way he seemed in his copy – friendly, with a radiant smile that came from somewhere deep inside, a great finisher of other people’s copy and an island of civility in the alcoholic haze that hung over the subs’ room in those days.

That was my first view of Harry and he never changed. In his late eighties he was still boyish, still curious, still enthusiastic, still generous.

He’d send you an email about a new book he’d just read. “This bloke can really write,” he’d say with all the excitement of an explorer who’s just discovered a new continent. He was eighty-nine going on seventeen.

Harry became editor of The Sun at the same time as Graham Perkin was editor of the Age.

On the night of the Faraday kidnappings the Sun was hours -- many hours -- ahead of us at the Age. The Sun had photos of the kidnapped school children in its first edition and we didn’t.

Graham rang Harry around midnight – I overheard the conversation -- and suggested Harry should give us the photos. In the public interest was the quaint way Graham put it. Harry, always the gentleman, said, yes, of course, he’d help, he’d never do anything against the public interest.

He put the phone down and after a very long delay – some say hours -- he handed the photos to a copy boy and told him to walk very slowly to the Age.

Harry, the former middleweight champ of Melbourne High, might have had gentle ways, but he was always the fiercest of competitors. If he had to knock you out, he always sent flowers to the hospital afterwards.

Harry held lots of other high editorial positions after he moved on from the Sun. But I’d suggest these were the lesser things.

Harry’s legacy is the stuff he wrote in newspapers and books – his words. His was always a human voice. I can’t recall him ever writing anything about infrastructure reform.

It was a voice so natural that it almost seemed that Harry wasn’t trying – which of course he was. But the effect was to give the reader the impression that the whole thing was just a happy accident – it just wrote itself. And so often it gave us, the readers, words and images that still run around in our heads.

We’re here to mourn Harry today.

But I remind you of something Red Smith, the great American sportswriter, wrote long ago after the death of a colleague he admired. Don’t mourn for the dead, Smith wrote, and went on to say:

This is a loss to the living, to everyone with a feeling for written English handled with respect and taste and grace.

So while we mourn for Harry today, we also need to mourn for us, the living. . . because Harry elevated us all, and made journalism look better than it really is, simply by his presence in the world.

[ends]