24 November 2015, Centennial Park, Adelaide, Australia

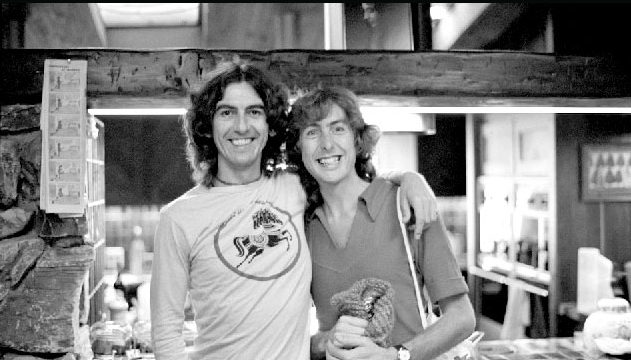

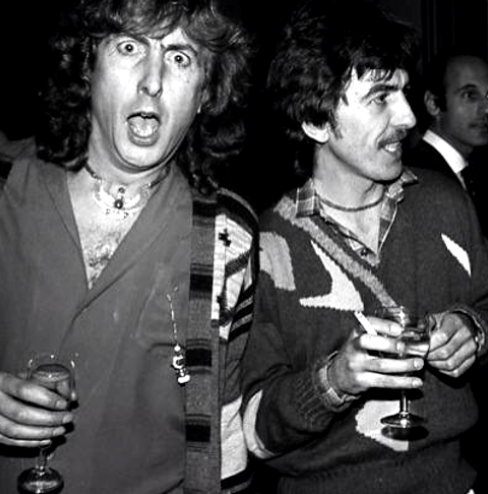

Mal Webb contributed original song Follicle Drive which he sang at the funeral. He is a songwriter, musician and instrumentalist from Melbourne. You can find his work here. His brother John Webb's magnificent eulogy is below.

Follicle Drive

The things I really loved

That I'll miss the most about my Dad

Are the things that could also drive me mad

He was a full on guy with a bursting brain

And a thirst for how and why

Sustained by a heart like a steam train

His ingrained sense of justice drove him on

Relentlessly he strove to champion what's right and fair

And all this with a gentlemanly air

And his voice, above all, would resound

Facts and stories would abound

Right into his anecdotage

Telling tangential tales related unabated

He was vaccinated with a gramophone needle

So he often stated

His many favourite phrases stay with me

Like music in my mind, they linger

While I picture that triumphant pointing of his finger

[Chorus]

"Aahh! That's fixed it, as good as a bought one

Aahh! You crumb! That's a wizard idea.

If dropped naked on a desert island, I would survive

Follicle Drive"

"Follicle Drive" is the name Dad gave to the subject of the research paper he was writing when he died.

His colleagues are continuing with his work.

Whether trains, lacrosse, genetics, fishing, rowing

Yes, whatever the endeavour he was keen as mustard

Truly an enthusiast

Infusing others with his eager educative passion

For doing stuff.

He loved lists and labels, fixing things, he hated waste

Post office red rubber bands on footpaths

would invariably end up in his pocket.

And I've ended up the same

I grew up helping with repairs

Soaked in brake fluid, acetone and Araldite

Holding torches for him, with him saying

"Shine it on my hands, not on my face!"

All to the soundtrack of the Goons

His science, I never understood

But I knew that it was good!

The sheer breadth of his intellect

So vast it brought us all to unexpected paths of thought

[Chorus]...

At the age of 5, to help me to explain my lack of red hair

He taught me how to say "it's a recessive gene".

He taught me sooo much

And in return, I taught him how to hug

And creative ways of eating something green.

His legendary high diaphram never really held him back.

And that crumb still had hair on his head

When he sailed over the horizon...

[Chorus]...

©Mal Webb 2015

The eulogy was delivered by Mal's brother, John Webb

Because I'm my father's son, my first impulse was to try to tell his whole story. Detailed, accurate, ordered: with headings, sub-headings, labels in Letraset: COMPLETE.

But then I was given ten minutes to do it. So, because I'm my father's son, I quickly realised I had to look at this from a different angle and then I got to work.

I can't fit a giant into a shoebox, but I can show you some of his works. My Dad was defined by, and now lives forever, through his works, and his deeds. He expressed his love for people through what he built or repaired for them, often when he had no other way to express it. When he handed you something he had just fixed he would loudly say, "THAT, is as good as a bought one" but he could possibly mean, "I have done you wrong, and I hope this makes it better".

Dad was a unique, passionate and complicated guy with a sometimes-confronting and intense manner, a huge voice and an odd turn of phrase. His voice helped him to be a superlative science teacher with a knack for keeping order in a big class, yet he had a rampant infectious enthusiasm that must have inspired many to pursue science as a career.

However as an aside, I should mention that Olivia Newton-John, whose charity we support today, was put on the road to success as an entertainer after Dad failed her in fifth form biology. A fact he was quite pleased about.

Dad used words that no-one else used. If you were annoying him you were a ‘crumb’, if you were annoying him a lot, you were an 'absolute crumb' , and if there were more than two of you, the collective noun was 'a pack'.

If something was really good it was 'wizard'. If you belonged to the medical profession, you were a 'medic', NEVER a Doctor.

I now refer you to the objects:

The crossbow.

This magnificent thing was built by Dad for his kids when we lived in Canberra in the seventies. You'll note that there is a Perspex view of the trigger mechanism, which he went to great lengths and much research to get right. It's an example of fine craftsmanship with hand tools. Each component was painted a different colour to demonstrate how it worked. It is a permanent reminder of Dad's high intellect, his lifelong obsession with finding out how things worked, and then his equal obsession with ensuring he passed on what he knew. He loved weaponry and the ingenuity of it, and he wanted this crossbow to work properly and in fact with spear gun rubber it was quite deadly. He handed it to us after delivering a very strongly worded procedure and safety demonstration and it provided many happy hours of target shooting.

Dad always insisted that no matter the age, kids needed to learn like adults. He would tell us facts without dumbing them down and could answer questions about literally anything. He was our Google. We learned to use real tools properly, we learned to tie on barbed fish hooks and use sharp knives, we rode bikes on the road and we learned correct scientific names for animals and plants. For me and my siblings, the yellow winged grasshoppers that swarmed the front lawn in Canberra were not "yellow wingers" as our friends called them, but Gastrimargus musicus.

Dad also taught us about chromosomes, and when I was about ten, he would take us to the Genetics department at Melbourne Uni and he would get us to carefully cut up photographs of karyotypes of locusts for his PhD thesis and mount them on card in their correct order for photographing. It was difficult work, but if you got it right consistently you were paid handsomely and we would all have pizza for lunch.

Life with Dad as a father could be that nice. But he could also be away a lot, and quick tempered with children, especially during the PhD years. My mother Susan was often left to manage four kids on her own, while he avidly pursued his other interests.

Dad found parenthood difficult. His own father was ill for many years and he had no sisters, so he was largely flying blind when my sister Cath arrived on the scene. Dad developed strong theories and rigid procedures for how to be a father to a daughter, and very early on, Cath began to give him strong feedback. Their relationship eventually became a long campaign between two great powers, each struggling desperately to change and understand the other. Sometimes there would be a truce, sometimes full scale war. By the time me, Mary and Mal came along, Cath had convinced Dad to soften his disciplinarian line. We were allowed to pursue our lives and careers where they took us, sometimes following Dad, sometimes following Mum, sometimes just going our own way. Dad was proud of us all and expressed amazement at what we all did. Cath ironically followed Dad into teaching, but in the arts, and became a talented ceramicist, then a conservationist. Mary followed Dad into science and science writing. Mal shrugged Dad's entreaties to become an engineer or mathematician, and instead leaned to Mum's side of the family and went headlong into a life of music. I became interested in agriculture and more particularly dairying, following my Mum's father's interest, but I also took Dad's advice and studied Ag science. However, I think if Dad was labelling my specimen jar honestly he'd now texta "MISCELLANEOUS" on it. Incidentally; peace was eventually declared between Cath and Dad. And it was a wonderful thing to see.

In the end, from Dad we inherited an exactly-against-the-odds hair colour gene expression, passion for what we do, four good brains and the understanding that working hard is the way to succeed. We now pass this on to our kids and Dad was always fascinated to see how the DNA had fallen and how his grandchildren were developing: sometimes he'd see a little of himself peering back at him, sometimes someone else entirely.

Again, I'm my father's son, and the discussion has wandered. One last remark about the crossbow. Dad's brother Neil's son, our cousin Simon, will be looking at the crossbow with horror. He came to visit us in Canberra when the crossbow was our new toy, and because he missed Dad's safety briefing, he used it to hunt blowflies in the garage, and learned that lead-tipped bolts bust windows.

The trains.

Dad built these models of the Victorian Railways S class steam locomotive and the S class diesel that superseded it in 1952. There were only ever four of these beautiful steam engines built and Dad always thought it was always a great tragedy that all of them were scrapped before anyone thought of preserving such things. And so do I.

Dad had an intense enthusiasm for all things rail and as kids we spent many very happy days on steam train trips with cinders in our eyes and hair, madly excited by the noise and the heat, the smell of coal, steam and oil and the drama of vintage steam locomotion. Dad would be totally absorbed in the engines and would bellow over the noise of a hissing safety valve to explain pistons, superheaters and motion gear to us. He'd laugh when the whistle made us jump. To this day, I hear a distant steam whistle and the impulse to dive into a car and find it is overwhelming, and so it was for Dad.

Train travel defined many of his life adventures. He deeply felt the romance of it. He would tell you a story of how he travelled by train to Seymour, and then to Puckapunyal for National service, and the fact that the train was hauled by an R class engine was the detail that finished the picture.

Travel also became part of our family culture. As kids we moved around following Dad's science career. Melbourne to Canberra then back to Melbourne then back to Canberra again. The family became used to moving, settling for a while then moving again.

We became good at keeping in touch with distant friends, but it also gave me a feeling that change was always around the corner and that people would always come and go.

Dad followed his passions and didn't have much interest in staying somewhere for the sake of appearing settled. And this led to him declaring in 1988 that he had one more move to make and it was to Adelaide. I believe that the choice between staying with Susan, the mother of his children and wonderful wife of twenty eight years, or to throw it all in to re-kindle a passionate romance with Noela must have been heartbreaking. At the time I was very angry at his decision, but eventually grew to respect that sometimes someone must just follow their heart. To the baffled spectator, Dad's relationship with Noela always seemed like an improbable mix of two opposites. But time is the ultimate judge, and they remained devoted to eachother for nearly thirty years.

Noela loses Dad to his fight with cancer at a time when she has her own epic struggle going on. All I can do is wish her strength and her family courage.

Where was I? The steam train model was actually meant to be the project I did for cubs, with parents allowed to help. But the project developed a life of its own, and Dad largely built it himself. I was allowed to paint some of it and screw in some wheels. It's a beautiful and faithful representation of an engine that Dad saw and loved as a boy and missed terribly forever. It includes a battery operated headlight that ingeniously uses the welding rod handrails to complete the circuit.

The diesel was built for Mal. Dad felt that it was a fitting conciliatory gesture to build a model of the engine that replaced the one he loved. No hard feelings.

The lacrosse sticks

The old stick.

Before you are possibly, the first and last lacrosse sticks that Dad ever repaired, with about 55 years between them. The glue is the same on both. Slow-set Araldite. Dad's adhesive of choice for most of his life. It was mixed of two parts and Dad always pointed out that the hardener was horrifically poisonous, usually while he was wiping off excess with a handkerchief that would then be stuffed back in his pocket, where it would later be used to blow his nose.

Dad started playing lacrosse when the gear was all wood and leather in the fifties. He and his brother played together and he always said that Keith was a much better player than he was, with a marvellously damaging shot on goal. Dad always did that. He underrated himself and he always generously compared himself unfavourably to others. It extended to all areas of his life: "Noela is much more intelligent than I am" he would say, or "your cousin Andrew is a much better fisherman than I am" or "I was never much chop as a lacrosse referee". It was an endearing trait, but it probably also contributed to his endless drive to improve and learn and then to teach. He was never quite satisfied with what he'd just done and always thought he could do better.

Lacrosse was his favourite sport and he was deeply involved for most of his life, though an intense involvement with the ANU rowing club intervened, filling the void during our five years in Canberra. Both sports have acknowledged Dad's passing this week, but the lacrosse community has reacted with overwhelming sadness. Dad co-founded the Eltham lacrosse club in 1963 and was a keen player, coach or supporter for all of the club's life, while it sometimes struggled and mostly thrived into the success we see today. However, he was a member of many clubs over the years including Melbourne University, Coburg, University High, Uni High Old Boys, Camberwell and Adelaide University.

He also helped to found the Doncaster club, which he had to sadly watch fold. He made it his business to help out struggling clubs and was loved and now remembered warmly for it. While Dad was very keen on the sport, he also thought himself a mediocre player, and would throw himself into the running of a club to compensate. People soon understood that to have Dad in your club was to be lucky enough to have a mad enthusiast, a tireless worker, a great recruiter, a patient skills coach, a talented gear mender and labeller and someone who saw things differently and who could bring lateral thinking to problems.

Oh, and it nearly went without saying: a great friend.

Everything seemed possible to Dad and he had no patience with anyone who said otherwise on the grounds that it had never been done, or would upset the status quo. He could often see the clear answer to a problem, but fail to see the politics in the background. It led to him once sadly saying to me that not being a better politician stopped him from getting to the top in many endeavours.

However, for all that, in the early eighties, Dad was a successful president of the then Victorian Amateur Lacrosse Association, He often said that he felt self-conscious about the fact that he was the first president who never played the sport at state level. Of course, it didn't matter. People in the sport valued him and voted for him because of his sense of fairness and the great things they'd seen him do at club level, and backed him to do the same in the role as president.

I followed my Dad into the sport with the Eltham club, along with my brother Mal for a time and even my sister Cath, who played for a while in a fledgling competition in Canberra. Don't look for it now.

Lacrosse is the sport that hardly anyone plays, or even knows about. Yet, most that do play can never get it out of their system. Dad was very happy to see his passion for lacrosse carried on and he recently said that for him it was completely addictive. A sport in which deft skill and real danger produces a beautiful spectacle. And so it is that I will play on next year for the Bendigo club, despite Dad's worry that I may get killed. Another mediocre player, trying to help out a struggling club in the best Webb tradition.

The modern stick

This stick is from Dad's time at his last club, Adelaide University. It has a nice action and Dad was very happy with how he'd repaired and re-strung it. Dad was a particularly fierce defender of the Adelaide and Melbourne University clubs' right to exist. Like many other clubs, the Adelaide Uni sent me wonderful messages from their members, paying tribute to Dad's passing as a massive loss to their club and their sport. It makes for sad reading, though there are moments to make you smile. One fellow made reference to Dad's unique ability to fill the tape on an answering machine. I laughed out loud, because I had the same trouble decades earlier and as a defence, I bought a machine that only allowed 30 seconds of message at a time. Instead of doing what everyone else did and summarise, Dad would ring 5 or 6 times to ensure he said his piece in full. He loved to talk and he was loud.

And that reminds me of a story. When Dad became ill with cancer, he brought to bear on it all his intelligence, his will to understand and his great bravery. He was wise and measured in how he sought treatment and gave himself the best possible chance to beat it. We held our breaths while he stared down surgery, and then chemotherapy, but I knew we had a fight on our hands when I rang him in hospital and at the other end came silence and then a faint voice. A small weak voice, lost in delirium.

My father’s voice always had permanence about it. It was his greatest trademark and the shock of hearing him quiet, bewildered, and with not much to say, will forever stay with me.

My wonderful siblings and I tried to come to Dad's rescue and with the help of some of Dad's devoted and amazing Adelaide friends and the outstanding care he got at Marten Aged Care he was given back his ability to be himself again. Something I'll always be thankful for. We had many great times before he died, especially lacrosse on the front lawn, with Dad teaching my boys the basic skills. But he was doomed and he never really got his voice back fully. I last saw him two weeks ago and there were some ominous signs and I have a clear picture in my mind of a final loving smile he gave me and tears starting in his eyes when he said "You'd better get out of here, I cry easily at the moment".

Alas, I now believe I have gone on a bit too long, but forgive me, I'm my father's son.