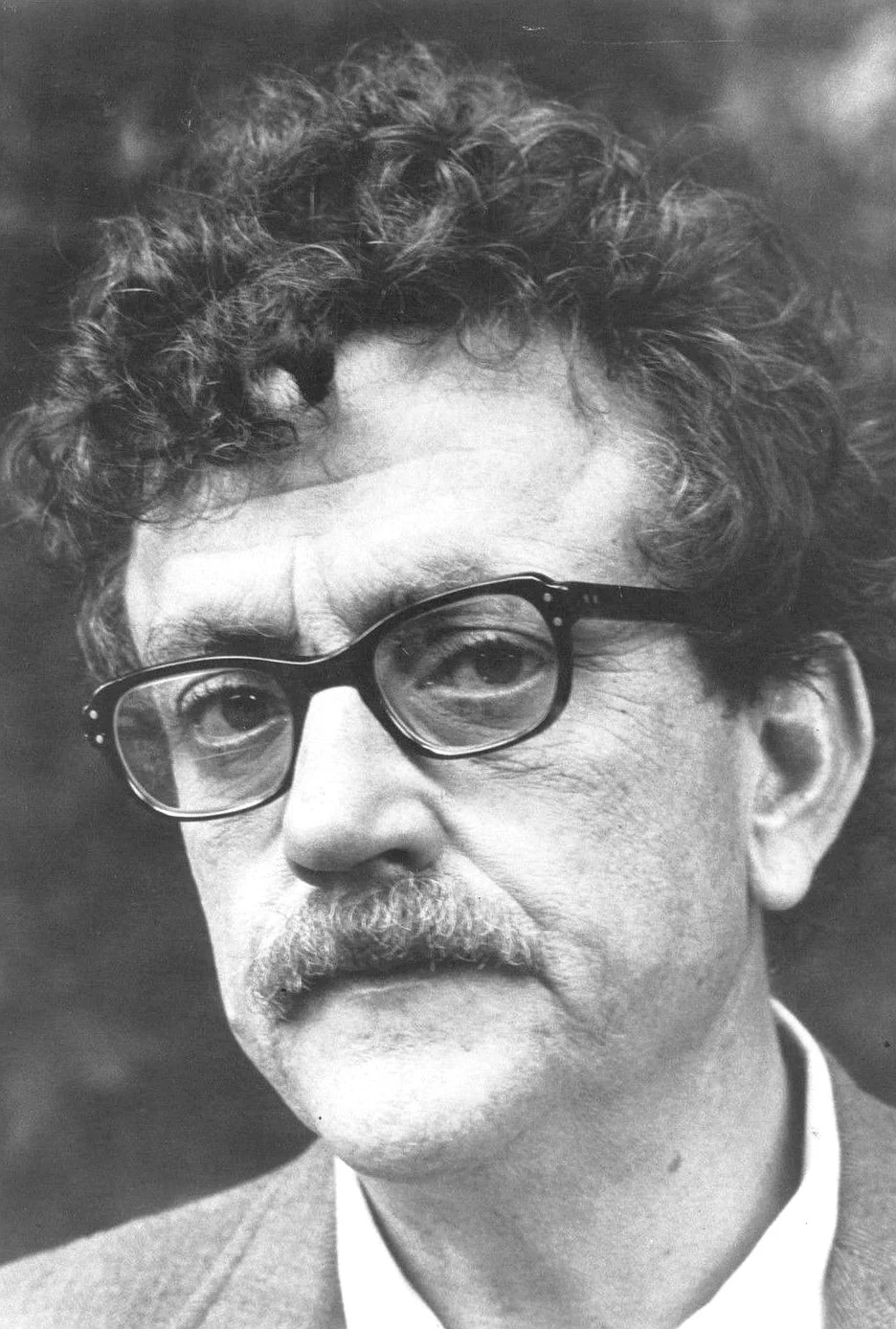

1970, Bennington College, Vermont, USA

I hope you will all be very happy as members of the educated class in America. I myself have been rejected again and again.

As I said on Earth Day in New York City not long ago: It isn't often that a total pessimist is invited to speak in the springtime. I predicted that everything would become worse, and everything has become worse.

One trouble, it seems to me, is that the majority of the people who rule us, who have our money and power, are lawyers or military men. The lawyers want to talk our problems out of existence. The military men want us to find the bad guys and put bullets through their brains. These are not always the best solutions—particularly in the fields of sewage disposal and birth control.

I demand that the administration of Bennington College establish an R.O.T.C. unit here. It is imperative that we learn more about military men, since they have so much of our money and power now. It is a great mistake to drive military men from college campuses and into ghettos like Fort Benning and Fort Bragg. Make them do what they do so proudly in the midst of men and women who are educated.

When I was at Cornell University, the experiences that most stimulated my thinking were in the R.O.T.C.—the manual of arms and close-order drill, and the way the officers spoke to me. Because of the military training I received at Cornell, I became a corporal at the end of World War Two. After the war, as you know, I made a fortune as a pacifist.

You should not only have military men here, but their weapons, too—especially crowd-control weapons such as machine guns and tanks. There is a tendency among young people these days to form crowds. Young people owe it to themselves to understand how easily machine guns and tanks can control crowds.

There is a basic rule about tanks, and you should know it: The only man who ever beat a tank was John Wayne. And he was in another tank.

Now then—about machine guns: They work sort of like a garden hose, execpt they spray death. They should be approached with caution.

There is a lesson for all of us in machine guns and tanks: Work within the system.

How pessimistic am I, really? I was a teacher at the University of Iowa three years ago. I had hundreds of students. As nearly as I am able to determine, not one of my ex-students has seen fit to reproduce. The only other demonstration of such a widespread disinclination to reproduce took place in Tasmania in about 1800. Native Tasmanians gave up on babies and the love thing and all that when white colonists, who were criminals from England, hunted them for sport.

I used to be an optimist. This was during my boyhood in Indianapolis. Those of you who have seen Indianapolis will understand that it was no easy thing to be an optimist there. It was the 500-mile Speedway Race, and then 364 days of miniature golf, and then the 500-mile Speedway Race again.

My brother Bernard, who was nine years older, was on his way to becoming an important scientist. He would later discover that silver iodide particles could precipitate certain kinds of clouds as snow or rain. He made me very enthusiastic about science for a while. I thought scientists were going to find out exactly how everything worked, and then make it work better. I fully expected that by the time I was twenty-one, some scientist, maybe my brother, would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty—and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine.

Scientific truth was going to make us so happy and comfortable.

What actually happened when I was twenty-one was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima. We killed everybody there. And I had just come home from being a prisoner of war in Dresden, which I'd seen burned to the ground. And the world was just then learning how ghastly the German extermination camps had been. So I had a heart-to-heart talk with myself.

"Hey, Corporal Vonnegut," I said to myself, "maybe you were wrong to be an optimist. Maybe pessimism is the thing."

I have been a consistent pessimist ever since, with a few exceptions. In order to persuade my wife to marry me, of course, I had to promise her that the future would be heavenly. And then I had to lie about the future again every time I thought she should have a baby. And then I had to lie to her again every time she threatened to leave me because I was too pessimistic.

I saved our marriage many times by exclaiming, "Wait! Wait! I see light at the end of the tunnel at last!" And I wish I could bring light to your tunnels today. My wife begged me to bring you light, but there is no light. Everything is going to become imaginably worse, and never get better again. If I lied to you about that, you would sense that I'd lied to you, and that would be another cause for gloom. We have enough causes for gloom.

I should like to give a motto to your class, a motto to your entire generation. It comes from my favorite Shakespearean play, which is King Henry VI, Part Three. In the first scene of Act Two, you will remember, Edward, Earl of March, who will later become King Edward IV, enters with Richard, who will later become Duke of Gloucester. They are the Duke of York's sons. They arrive at the head of their troops on a plain near Mortimer's Cross in Herefordshire and immediately receive news that their father has had his head cut off. Richard says this, among other things, and this is the motto I give you: "To weep is to make less the depth of grief."

Again: "To weep is to make less the depth of grief."

It is from the same play, which has been such a comfort to me, that we find the line, "The smallest worm will turn being trodden on." I don't have to tell you that the line is spoken by Lord Clifford in Scene One of Act Two. This is meant to be optimistic, I think, but I have to tell you that a worm can be stepped on in such a way that it can't possibly turn after you remove your foot.

I have performed this experiment for my children countless times. They are grown-ups now. They can step on worms now with no help from their Daddy. But let us pretend for a moment that worms can turn, do turn. And let us ask ourselves, "What would be a good, new direction for the worm of civilization to take?"

Well—it should go upward, if possible. Up is certainly better than down, or is widely believed to be. And we would be a lot safer if the Government would take its money out of science and put it into astrology and the reading of palms. I used to think that science would save us, and science certainly tried. But we can't stand any more tremendous explosions, either for or against democracy. Only in superstition is there hope. If you want to become a friend of civilization, then become an enemy of truth and a fanatic for harmless balderdash.

I know that millions of dollars have been spent to produce this splendid graduating class, and that the main hope of your teachers was, once they got through with you, that you would no longer be superstitious. I'm sorry—I have to undo that now. I beg you to believe in the most ridiculous superstition of all: that humanity is at the center of the universe, the fulfiller or the frustrator of the grandest dreams of God Almighty.

If you can believe that, and make others believe it, then there might be hope for us. Human beings might stop treating each other like garbage, might begin to treasure and protect each other instead. Then it might be all right to have babies again.

Many of you will have babies anyway, if you're anything like me. To quote the poet Schiller: "Against stupidity the very gods themselves contend in vain."

About astrology and palmistry: They are good because they make people feel vivid and full of possibilities. They are communism at its best. Everybody has a birthday and almost everybody has a palm. Take a seemingly drab person born on August 3, for instance. He's a Leo. He is proud, generous, trusting, energetic, domineering, and authoritative! All Leos are! He is ruled by the Sun! His gems are the ruby and the diamond! His color is orange! His metal is gold! This is a nobody?

His harmonius signs for business, marriage, or companionship are Sagittarius and Aries. Anybody here a Sagittarius or an Aries? Watch out! Here comes destiny!

Is this lonely-looking human being really alone? Far from it! He shares the sign of Leo with T. E. Lawrence, Herbert Hoover, Alfred Hitchcock, Dorothy Parker, Jacqueline Onassis, Henry Ford, Princess Margaret, and George Bernard Shaw! You've heard of them.

Look at him blush with happiness! Ask him to show you his amazing palms. What a fantastic heart line he has! Be on your guard, girls. Have you ever seen a Hill of the Moon like his? Wow! This is some human being!

Which brings us to the arts, whose purpose, in common with astrology, is to use frauds in order to make human beings seem more wonderful than they really are. Dancers show us human beings who move much more gracefully than human beings really move. Films and books and plays show us people talking much more entertainingly than people really talk, make paltry human enterprises seem important. Singers and musicians show us human beings making sounds far more lovely than human beings really make. Architects give us temples in which something marvelous is obviously going on. Actually, practically nothing is going on inside. And on and on.

The arts put man at the center of the universe, whether he belongs there or not. Military science, on the other hand, treats man as garbage—and his children, and his cities, too. Military science is probably right about the comtemptibility of man in the vastness of the universe. Still—I deny that contemptibililty, and I beg you to deny it, through the creation of appreciation of art.

A friend of mine, who is also a critic, decided to do a paper on things I'd written. He reread all my stuff, which took him about two hours and fifteen minutes, and he was exasperated when he got through. "You know what you do?" he said. "No," I said. "What do I do?" And he said, "You put bitter coatings on very sweet pills."

I would like to do that now, to have the bitterness of my pessimism melt away, leaving you with mouthfuls of a sort of vanilla fudge goo. But I find it harder and harder to prepare confections of this sort—particularly since our military scientists have taken to firing at crowds of their own people. Also—I took a trip to Biafra last January, which was a million laughs. And this hideous war in Indochina goes on and on.

Still—I will give you what goo I have left.

It has been said many times that man's knowledge of himself has been left far behind by his understanding of technology, and that we can have peace and plenty and justice only when man's knowledge of himself catches up. This is not true. Some people hope for great discoveries in the social sciences, social equivalents of F=ma and E=mc^2, and so on. Others think we have to evolve, to become better monkeys with bigger brains. We don't need more information. We don't need bigger brains. All that is required is that we become less selfish than we are.

We already have plenty of sound suggestions as to how we are to act if things are to become better on earth. For instance: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. About seven hundred years ago, Thomas Aquinas had some other recommendations as to what people might do with their lives, and I do not find these made ridiculous by computers and trips to the moon and television sets. He praises the Seven Spiritual Works of Mercy, which are these:

To teach the ignorant, to counsel the doubtful, to console the sad, to reprove the sinner, to forgive the offender, to bear with the oppressive and troublesome, and to pray for us all.

He also admires the Seven Corporal Works of Mercy, which are these:

To feed the hungry, to give drink to the thirsty, to clothe the naked, to shelter the homeless, to visit the sick and prisoners, to ransom captives, and to bury the dead.

A great swindle of our time is the assumption that science has made religion obsolete. All science has damaged is the story of Adam and Eve and the story of Jonah and the Whale. Everything else holds up pretty well, particularly the lessons about fairness and gentleness. People who find those lessons irrelevant in the twentieth century are simply using science as an excuse for greed and harshness.

Science has nothing to do with it, friends.

Another great swindle is that people your age are supposed to save the world. I was a graduation speaker at a little preparatory school for girls on Cape Cod, where I live. I told the girls that they were much too young to save the world and that, after they got their diplomas, they should go swimming and sailing and walking, and just fool around.

I often hear parents say to their idealistic children, "All right, you see so much that is wrong with the world—go out and do something about it. We're all for you! Go out and save the world."

You are four years older than those prep school girls but still very young. You, too, have been swindled, if people have persuaded you that it is now up to you to save the world. It isn't up to you. You don't have the money and the power. You don't have the appearance of grave maturity—even though you may be gravely mature. You don't even know how to handle dynamite. It is up to older people to save the world. You can help them.

Do not take the entire world on your shoulders. Do a certain amount of skylarking, as befits people of your age. "Skylarking," incidentally, used to be a minor offense under Navel Regulations. What a charming crime. It means intolerable lack of seriousness. I would love to have a dishonorable discharge from the United States Navy—for skylarking not just once, but again and again and again.

Many of you will undertake exceedingly serious work this summer—campaigning for humane Senators and Congressmen, helping the poor and the ignorant and the awfully old. Good. But skylark, too.

When it really is time for you to save the world, when you have some power and know your way around, when people can't mock you for looking so young, I suggest that you work for a socialist form of government. Free Enterprise is much too hard on the old and the sick and the shy and the poor and the stupid, and on people nobody likes. The just can't cut the mustard under Free Enterprise. They lack that certain something that Nelson Rockefeller, for instance, so abundantly has.

So let's divide up the wealth more fairly than we have divided it up so far. Let's make sure that everybody has enough to eat, and a decent place to live, and medical help when he needs it. Let's stop spending money on weapons, which don't work anyway, thank God, and spend money on each other. It isn't moonbeams to talk of modest plenty for all. They have it in Sweden. We can have it here. Dwight David Eisenhower once pointed out that Sweden, with its many utopian programs, had a high rate of alcoholism and suicide and youthful unrest. Even so, I would like to see America try socialism. If we start drinking heavily and killing ourselves, and if our children start acting crazy, we can go back to good old Free Enterprise again.