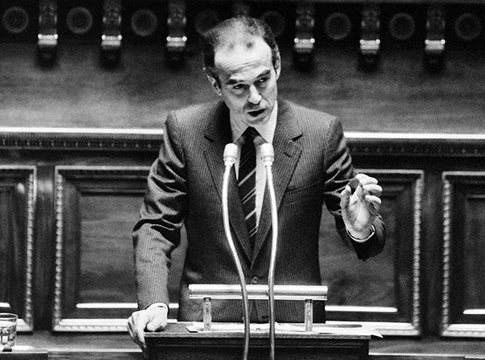

28 September 1981, French National Assembly, Paris, France

The French transcript of Justice Minister Badinger's reasons for seeking abolition of the death penalty is here. This is an incomplete English transcript.

M. President: I give the floor to M. Guard of the Seals, Minister of

Justice.

M. Robert Badinter: M. President, ladies and gentlemen, I have the honour, on behalf of the Government of the Republic, to submit to the National Assembly the abolition of capital punishment in France.

In that moment, whose significance each of you can realise for our justice and for us, I want, first and foremost, to thank the Commission of Laws, because it understood the spirit of the bill submitted to it, and more particularly its recorder, M. Raymond Forni, not only because he is a man of heart and of talent, but also because he has been fighting, over the past

years, for abolition. Beyond himself, and like him, I’d like to thank all those, regardless of their political orientations, who, all along the past years, and especially inside the previous Commissions of Laws, have also been working so that abolition be decided, even before the major political shift we’ve just experienced.

This spiritual communion, this community of thought through political splits, do show that the debate opened today in front of you is first a debate of conscience and the choice that everyone of you will make shall bind him personally.

Raymond Forni rightly underlined that we’re about to finish a long way.

Nearly two centuries took place since, in the first parliamentary assembly in France, Le Pelletier de Saint-Fargeau called for the abolition of capital punishment. That was in 1791.

I’m looking at the way covered by France since then. France is a great country, not only by its power, but also, beyond its power, by the brilliance of the ideas, the causes, the generosity that prevailed during the important moments of her history.

France is a great country because she was the first, in Europe, to abolish torture in spite of cautious minds who, throughout the country, argued, at that time, that without torture, French justice would be helpless and that, without torture, good subjects would be handed over to the villains.

France was one of the first countries to abolish slavery, this crime that dishonours humanity.

That being said, and in spite of so many courageous attempts, France will have been one of the last countries, almost the last one – and I lower my voice to say that – in Western Europe, a continent where she has so often been a centre and a pole, to abolish capital punishment.

Why this delay? This is the first question that we must face.

It isn’t a problem of national genius. It’s from France, often from this forum, that the most famous voices, the ones that resonated to the highest and the furthest points in human conscience, arose to support, with utmost eloquence, the cause of abolition. M. Forni, you very appropriately recalled Hugo, I would recall as well, among other writers, Camus. And how not to think, in this very forum, about GambettaClemenceau and especially the great Jaurès?

They all stood up. They all supported the cause of abolition. So why did silence continue, why haven’t we abolished capital punishment?

I don’t either think it could be because of our national temperament. The French aren’t more repressive, less humane than other people. I know it by experience. French judges and juries can be as generous as other ones.

The answer thus doesn’t lie here. We have to seek it elsewhere.

For myself, I can see an explanation of political nature. Why? Abolition, as I said, has been regrouping men and women from every political class, and, beyond this, from all the layers of the nation. But if one considers the history of our country, one will notice that abolition, as such, has always been one of the great causes of the French left.

By left, understand me well, I mean forces of change, forces of progress, sometimes forces of revolution, those who, in any way, get history to progress. (Applause among the socialist representatives, many communists and from a few benches of the Union for the French Democracy)

Just look at this truth.

I recalled 1791, the first Constituent assembly. It’s true it didn’t abolish capital punishment, but it raised the issue, which was prodigiously audacious at that time. It reduced the application field of capital punishment more than anywhere else in Europe.

France’s first Republican Assembly, the Great Convention, proclaimed, on 4 Brumaire Year IV of the Republic, that capital punishment would be abolished in France once general peace would be re-established.

M. Albert Brochard: We know where this led to in Vendée!

Several socialist representatives: Silence Chouans !

M. Robert Badinter: Peace was eventually re-established, but with it Bonaparte arrived. And death penalty was written in the books of the Criminal Code that still is ours, not for long, though.

But let’s follow history.

The 1830 Revolution generated, in 1832, the concept of extenuating circumstances; the number of death sentences was immediately halved. The 1848 Revolution brought the abolition of capital punishment in political crimes, a progress that wouldn’t be put in question, in France, until 1939.

Not until the establishment of a left-wing majority in the core of French politics, in the years after 1900, shall again be submitted to the representatives of the people the question of the abolition of capital punishment. At that time, in this forum, Barrès and Jaurès confronted each other in a debate whose eloquence history still remembers. Jaurès – whose memory I honour on your behalf – has been, among all the left-wing orators, among all the socialists, the one who had the highest, the furthest and the most noble eloquence of heart and of reason, in order to serve, as a person, socialism, liberty and abolition. (Applause on the socialist benches, as well as on several communist benches.)

Jaurès... (Interruptions from the benches of the Union for the French Democracy and Movement for the Republic: Are there still names that disturb some of you? (Applause from the socialist and communist benches.)

M. Michel Noir: It’s deliberate provocation!

M. Jean Brocard: You’re not at court, but in front of the Assembly!

M. President: Sirs from the opposition, please. Jaurès belongs, together with other politicians, to the history of our country. (Applause from the same benches.)

M. Roger Corrèze: But not Badinter!

M. Robert Wagner: You don’t have your sleeves, M. Guard of the Seals!

M. President: Would you please carry on, M. Guard of the Seals.

M. Robert Badinter: Sirs, I recalled the memory of Barrès in spite of the distance between our opinions on this matter; I thus don’t need to insist. But I have to recall, since, obviously, his words aren’t extinct inside you, this sentence pronounced by Jaurès: “Capital punishment is contrary to what humanity, for two thousand years, has been thinking as highest and has been

dreaming as most noble. It is contrary to the spirit of Christianity as well as to the spirit of revolution.”

In 1908, Briand, in his turn, undertook submitting abolition to the Assembly. Curiously though, he didn’t attempt to use his eloquence. He strove to convince the Assembly by making it observe a very simple data, that recent experience – findings of the positivist school of thought – had just brought to light.

He actually observed that, due to different temperaments of the Presidents that succeeded one another during that period of great social and economic stability, the practice of capital punishment had notably changed for two decades: 1888-1897, Presidents let executions take place; 1898-1907, Presidents - Loubet, Fallières –abhorred capital punishment and consequently gave systematically pardon. The data were clear : during the former period

when executions were carried out : 3,066 homicides ; during the latter period, when human gentleness created reluctance on executions and capital punishment disappeared from repressive practice : 1,068 homicides, almost half of the former.

For this reason, Briand, irrespective of principles, invited the Assembly to abolish capital punishment that, as had been measured, was not dissuasive. It happened that a part of the press immediately undertook a very violent campaign against the abolitionists. It happened that a part of the Representatives didn’t have the courage to do what Briand suggested they

did. That’s how capital punishment stayed, in 1908, in our law and in our practice.

Since then – 75 years – never has a Parliamentary Assembly been submitted a bill to abolish capital punishment.

I am convinced – this will please you – that I have less eloquence than Briand, but I’m sure that you, you will have more courage, and that’s what matters.

M. Albert Brochard: Is that courage?

M. Robert Aumont: This interruption is inappropriate!

M. Roger Corrèze: There have also been left-wing governments during all

those years!

M. Robert Badinter: Time went by. One can wonder : why did nothing evolve in 1936? The reason is that the time of the left-wing was too short. The other reason, more simply, is that war was already looming in minds. And war periods aren’t favourable to tackle

the question of abolition of capital punishment. It is true that war and abolition can’t occur together.

Liberation. I’m convinced, on my part, that, if the government of Liberation didn’t raise the issue of abolition, it’s because troubled times, war crimes, the terrible ordeals of occupation caused the sensibility of public not to be ready for this. It was necessary to re-establish not only civil peace, but also peace among hearts.

This analysis is also valid for decolonisation periods. Only after those historical ordeals could really the question of abolition be submitted to your Assembly.

I shan’t elaborate more on this – M. Forni did that – but why, along the past mandate of this Assembly, didn’t governments want to raise, to your Assembly, the question of abolition, as so many of you, courageously, called for this debate? Some members of the government – and important ones – proclaimed themselves, personally, in favour of abolition, but one had the

feeling, hearing those whose responsibility was to propose abolition, that, on this issue, it was necessary to wait.

Wait, after 200 years!

Wait, as if capital punishment or guillotine were a fruit that one had to let mature before picking it!

Wait? We know, in reality, that the cause for this was the fear of the public opinion. Besides, some would tell you, ladies and sirs representatives, that, by voting for abolition, you would disregard the rules of democracy and ignore public opinion. This is wrong.

No one, at the time of the vote, will respect more than you the fundamental rule of democracy.

I refer myself not only to this conception, according to which the Parliament is, following the image of a famous Englishman, a lighthouse that opens the way from obscurity to our country, but also to the fundamental law of democracy that is the voice of universal vote and, for the ones who were elected, the respect of universal vote.

And, on two occasions, the question was directly – I emphasise this word – raised to the public opinion. The President made publicly know, not only his personal feeling, his loathing for capital punishment, but also expressed very clearly his will to ask the government to submit abolition to the Parliament if he was elected. The country answered: yes. Then there were the Parliament elections. During the electoral campaign, each one of the left-wing parties mentioned publicly in its programme…

M. Albert Brochard: What programme?

M. Robet Badinter: ... the abolition of capital punishment.

This country elected a left-wing majority; by so doing, with full knowledge, electors knew that they were approving a legislative programme in which the abolition of capital punishment stood at the first rank of its moral commitments. When you will vote for it, this solemn pact, the one that binds the representative to the country and that gives you as first duty the respect of the commitments you were elected for, respect for the universal vote of

the nation and for democracy, shall finally be yours.

Others will tell you that abolition, because it raises a problem to each and every human conscience, should only be decided by a referendum. If this choice existed, the question would probably have to be considered. But you know it as well as I do, and Raymond Forni recalled it, this possibility is constitutionally closed.

I recall the Assembly – but do I actually need to do it? – that General de Gaulle, founder of the Vth Republic, didn’t wish that matters of society, or, if you prefer, matters of morals, be decided through referendum. Neither do I need to recall you, ladies and gentlemen, that criminal penalties for abortion as well as for capital punishment stand in the books

of criminal laws that, according to the Constitution, come under your only

prerogatives.

Consequently, arguing that a referendum should take place, willing to solve the issue only by referendum, is deliberately ignoring the spirit as well as the letter of the Constitution. It is, by fake cleverness, refusing to take publicly a decision by fear of the public opinion. (Applause from socialist benches and from a few communist benches.)

Nothing has been made, through the past years, to enlighten the public opinion. On the contrary!

One refused the experience of abolitionist countries; one never wondered how the great Western democracies, our close partners, our sisters, our neighbours, could live without capital punishment.

One neglected studies made by all the greatest international organisations, such as the Council of Europe, the European Parliament, the United Nations themselves inside the Committee of Criminal Studies.

One concealed their constant conclusions. It has never been demonstrated that

there was any correlation between the existence or the non-existence of capital punishment in criminal legislation and the curve of lethal crime. On the contrary, instead of disclosing and underlining those obvious points, one kept anguish and fears alive, one favoured confusion.

One blocked the focus on the indisputable and worrisome increase of small and medium violent delinquency: we have, of course, to face this problem that is linked to economic and social conditions, and that, anyway, never came under capital punishment. But all honest people agree on the fact that, in France, lethal crime has never changed – and actually, taking the number of inhabitants into account, it rather tends to stagnate.

One kept silent.

In one word, regarding the public opinion, one stirred up collective fears and one refused it the defences of reason. (Applause from socialist benches and from a few communist benches.)

In reality, the question of capital punishment is easy for anyone who wants to analyse it with lucidity. It doesn’t come in terms of dissuasion or of repressive techniques, but in terms of political and moral choice. I have already said it, but I gladly repeat it, in regard of former silence: the only result reached by all the studies undertaken by specialists in criminology, is the conclusion of absence of relation between capital punishment and the evolution of lethal crime. I recall again, in this regard, the works of the Council of Europe in 1962; the British White Paper, a prudent research led throughout all the abolitionist countries before the

British decided to abolish capital punishment and refused since then, on two occasions, to restore it; the Canadian White Paper which processed according to the same method ; the studies led by the Committee for Crime Prevention of the United Nations, whose last texts were elaborated last year in Caracas; and finally the studies of the European Parliament, to which I associate our friend Mrs Roudy, that ended up to this essential vote by

which that Assembly, on behalf of Europe that it represents, of Western Europe of course, called, with an overwhelming majority, for the disappearance of capital punishment in Europe.

All, all of them concur on the conclusion I underlined.

Besides, for anyone who wants to consider faithfully the problem, it isn’t difficult to understand why, between capital punishment and the evolution of lethal crime, there is no such dissuasive link that one so often attempted to look for, without ever finding its source. I shall come back on this in a moment. If you simply look at this, the most horrendous crimes, those that shock the most the sensitiveness of the public – and one understands that -, those qualified as most atrocious crimes are most often committed by men driven by impulse of violence and death that go as far as suppressing the defences of reason. At that moment of madness, at that time of murderous impulse, the evocation of the penalty, whether it is capital punishment or

life without parole, is non existent in the mind of the murderer.

Don’t tell me that those mad ones aren’t sentenced to death. One could just refer to the annals of the past years to be convinced of the contrary. Olivier, executed, whose autopsy revealed his brains had frontal abnormalities. And Carrein, and Rousseau, and Garceau. As for the others, the so-called cold-blooded criminals, those who consider risks, those who think about the profits and the penalty, those ones, you shall never find them in situations where they risk their necks.

Reasonable gangsters, crime profiteers, organised criminals, procurers, traffickers, mafioso, never shall you find them in such situations. Never! (Applause from socialist benches and from a few communist benches.)

Those who look at the judicial annals, because those annals enclose the reality of capital punishment, know that, during the last 30 years, one cannot find the name of a “great” gangster, if one can use this adjective to qualify that kind of person. Not a single “public enemy” has never appeared there.

M. Jean Brocard: And Mesrine?

M. Hyacinthe Santoni: And Buffet? And Bontems?

M. Robert Badinter: It is the other ones, the former ones I evoked before, that appear in those annals. Actually, those who believe in the dissuasive value of capital punishment are unaware of human truth. Criminal passions cannot be held any more than other passions that, on the contrary, are noble. And if the fear of death could stop men, you would have no great soldiers,

no great sportsmen. We admire them, but they don’t hesitate in front of death. Others, driven by other passions, don’t hesitate either. Only to justify capital punishment did one invent the idea that the fear of death would stop men from their extreme passions.

This is not correct. And, since someone just pronounced the name of two death row inmates that were executed, I will explain to you why, more than anyone else, I can affirm that capital punishment has no dissuasive value: remember that, among the crowd that, around the Palace of Justice of Troyes, shouted “To death Buffet! To death Bontems” after the imposition of their death sentences, there was a young man whose name was Patrick Henry. Believe me, when I learnt that, to my amazement, I understood what the dissuasive value of capital punishment could mean ! (Applause from socialist benches and from a few communist benches.)

M. Pierre Micaux: Go to Troyes to explain it!

M. Robert Badinter: And you, who are statesmen, conscious of your responsibilities, do you believe that Statesmen, our friends who are responsible for leading the great Western democracies, as meaningful astheir respect for those moral values, that are characteristic for countries of freedom, can be, do you believe that those responsible men would have voted abolition or that they wouldn’t have restored capital punishment if they had thought it could have been of any use, thanks to its dissuasive value, against lethal crime? Thinking so would be an insult to them.

M. Albert Brochard: And in California? Reagan is probably a wag!

M. Robert Badinter: We shall forward him those remarks. I’m sure he’ll appreciate the qualifier!

It is anyway sufficient to question yourselves, in concrete terms, and realise what abolition would have exactly meant if it had been voted in France in 1974, when the previous President, though always privately, recognised his personal loathing for capital punishment.

What would have been the impact of abolition voted in 1974, for the 7-year-term that ended in 1981, on the safety and security of the French? Just this: three death row inmates that would add up to the 333 inmates presently in our jails. Three more.

Who? I will recall you.

Christian Ranucci: I shan’t insist here, there are too many interrogations and doubts about him, and those interrogations are sufficient, for any conscience longing for justice, to disapprove capital punishment.

Jérôme Carrein: feeble, drunkard, he committed an atrocious crime. But he was also seen by many in his village, giving his hand to the little girl he would kill a few moments later, and this shows that he didn’t realise the passion that would overwhelm him then. (Murmuring from many benches of the Movement for the Republic and Union

for the French Democracy.)

Finally Djandoubi, who was one-legged and who, whatever the horror of his crimes – and the term isn’t too strong -, showed obvious signs of unbalance and who was brought to the guillotine after having removed his prosthesis.

I certainly don’t want to call for any posthumous pity: it’s neither the place, nor the time for this, but just keep in mind that one still have questions about the guilt of the former, that the second one was a feeble and that the first one was one-legged.

Can one argue that, if those three men were in French jails, the safety of our citizens would in any way be endangered?

M. Albert Brochard: That’s incredible! We’re not at court!

M. Robert Badinter: That’s truth and the exact impact of capital punishment. It’s simply that. (Prolonged applause from socialist and communist benches.)

M. Jean Brocard: I’m leaving this meeting.

M. President: It’s your right!

M. Albert Brochard: You’re Guard of the Seals and not lawyer!

M. Robert Badinter: And this reality...

M. Roger Corrèze: Your reality !

M. Robert Badinter: ... seems to make people leave. As we all know, the question is not in terms of dissuasion or repressive technique, but in terms of political, and especially moral choice.

A single look at a world map can confirm that capital punishment has a political meaning. I regret one cannot submit such a map to this Assembly, as it was done at the European Parliament. One would see the abolitionist countries and the other ones, the countries of freedom and the other ones.

M. Charles Miossec: What a strange combination!

M. Robert Badinter: Facts are clear. In the overwhelming majority of Western democracies, especially in Europe, in all the countries where freedom stands in institutions and is respected in practice, capital punishment has disappeared.

M. Claude Marcus: Not in the United States.

M. Robert Badinter: I said in Western Europe, but it is significant that you mention the United States. The copy is almost complete: in countries of freedom, the common law is abolition, capital punishment is the exception.

M. Roger Corrèze: Not in socialist countries.

M. Robert Badinter: I’m not putting these words into your mouth. Everywhere in the world, and with no exception, where dictatorship and violations for human rights prevail, everywhere shall you find out that capital punishment stands, in red letters.

(Applause from socialist benches.)

M. Roger Corrèze: The communists took note of your words!

M. Gérard Chasseguet: The communists have appreciated.

M. Robert Badinter: Here’s the first obvious point: in countries of freedom, abolition is almost the rule; in dictatorships, capital punishment is everywhere in use. This division of the world doesn’t result from just a coincidence. It shows a correlation. The true political signification of capital punishment is that it results from the idea that State has the right to take advantage of the citizen, till the possibility to suppress the citizen’s life. This is the way capital punishment comes within the framework of totalitarian regimes.

Here you will find, in the judicial reality, as Raymond Forni evoked, the true signification of capital punishment. In the judicial reality, what is capital punishment? It is twelve men and women, two days of hearings, theimpossibility to get to the bottom of the facts and the terrible duty to decide, in a few quarters of an hour, sometimes even in a few minutes, on

the so difficult question of guilt and, beyond this, on the life or the death of another human being.

Twelve persons, in a democracy, that have the right to say: this one shall live, that one shall die! I affirm it: this conception of justice cannot be the one of countries of freedom, precisely

because of its totalitarian significance.

As regards right to pardon, we should, as Raymond Forni recalled it, question ourselves about it. When the king was representing God on the Earth, when he was anointed by God’s will, the right to pardon had a legitimate foundation. In a civilisation, in a society whose institutions

are imbued by religious faith, one can easily understand that God’s representative may have had this right of life and death. But in a republic, in a democracy, whatever his merits are, whatever his conscience is, no man, no power should have, at his disposal, any right on anyone in time of peace.

M. Jean Falala: Except the murderers!

M. Robert Badinter: I know that nowadays - and this is the main problem -, some of you consider capital punishment as a kind of ultimate resort, a kind of extreme defence of democracy against the serious threat represented by terrorism. Guillotine, they think, would possibly protect democracy instead of dishonouring it.

This argument reveals a complete ignorance of reality. Indeed, History shows that, if there is a category of crime that has never backed out in front of the threat of death, it is political crime. And, more specifically, if there is a kind of woman or man that the threat of death couldn’t make hesitate, it is the terrorist. First, because he faces death during his violent action; then, because deep down in his heart, he feels some dark fascination over violence and death, the one he gives, and also the one he receives.

Terrorism, which, for me, is a major crime against democracy, and that, should it take place in this country, would be repressed and prosecuted with all necessary steadiness, has, as a rallying cry, whatever the ideology that motivates it, the terrible cry of the fascists during the Spain War: "Viva la muerte!". So, believing that one could stop it with death is illusion.

Let’s go further. If, in the neighbouring democracies, yet confronted toterrorism, one refused to restore capital punishment, it is, of course, out of moral requirements, but also for political reasons. You know actually that, to the eyes of some, especially the youth, the execution of a

terrorist would transcend him, divert him from the criminal reality of his deeds, transform him into a kind of hero who has fought till the end of his life, who, having been involved in a cause, as obnoxious as this cause be, would have served it till his death. Then there is a considerable risk, that precisely the Statesmen of our neighbouring democracies considered, to see

the emergence, in the shadow, of twenty wandered youth for each terrorist killed. So, instead of fighting terrorism, capital punishment would feed terrorism. (Applause from socialist and communist benches.)

To this factual consideration, one should add a moral data: using capital punishment against terrorists is, for a democracy, adopting the values of the terrorists. When, after having arrested him, after having extorted from him terrible correspondences, terrorists, at the end of a degrading mockery of trial, execute the one they abducted, not only do they commit an

obnoxious crime, but they also set a most insidious trap for democracy, the trap of a murderous violence that, by compelling that democracy to resort to capital punishment, might enable them to give that democracy, as a result of an inversion of values, their own savage face.

We must refuse that temptation without ever, though, compromising with this ultimate form of violence, intolerable in a democracy, that terrorism represents. But after one has stripped the problem from its passionate aspect and one wants to reach to the bottom with lucidity, one notes that the choice between retention and abolition of capital punishment is, at the end of the day and for each of us, a moral choice.

I won’t use the argument of authority, because it would be inappropriate at the Parliament, and too easy in this forum. But one can’t miss noticing that, over the past years, the catholic church, the council of the reformed church and the representatives of the Jewish community all clearly took position against capital punishment. How not to recall that all the great

international organisations that campaign, throughout the world, for the defence of human rights – Amnesty International, the International Association for Human Rights, the Human Rights League – have all campaigned for the abolition of capital punishment.

M. Albert Brochard: Except the families of the victims (Prolonged murmuring from socialist benches.)

M. Robert Badinter: This conjunction of so many religious and secular beliefs, men of God as well as men of freedoms, at a period when one evokes so often a crisis of moral values, is significant.

M. Pierre-Charles Krieg: And 33% of the French!

M. Robert Badinter: For the advocates of capital punishment, whose choice the abolitionists, including myself, have always respected, while noting with regret that the opposite wasn’t always true, and that hatred often answered what was only the expression of a deep conviction, which I shall always respect in men of freedom – for the advocates of capital punishment, as I said, the death of the guilty is a requirement for justice. For them,

there are indeed crimes that are so atrocious that one couldn’t enable the criminals to expiate for them in another way than by paying their lives.

The death and sufferings of the victims, this terrible misfortune, would demand, as a necessary and imperative compensation, another death and other sufferings. Failing that, as a recent Minister of Justice has recently stated, anguish and passion aroused in society by crime would not be soothed. That is called, I believe, an expiatory sacrifice. And justice, for the advocates of capital punishment, would not be done if, to the death of the victim, the death of the guilty didn’t response, like an echo.

Lets’ be clear. This just means that the “an eye for an eye” principle would stay, throughout the millennia, the necessary, unique law of human justice. Talking about misfortune and sufferings of victims, I have, more often than those who mention them, measured, throughout my life, their extent. That crime is the meeting point of human misfortune, I know it better than

anyone. Misfortune for the victim herself and, beyond, misfortune for her parents and relatives. Misfortune for the parents of the criminal.

Finally, misfortune for the criminal himself. Yes, crime is misfortune and there is no man, no woman of heart, of reason, of responsibility, who wouldn’t want first to fight crime But feeling, deep inside oneself, the misfortune and the sorrow of victims, fighting by all means so that violence and crime regress in our society, this sensitivity and this fight cannot imply the necessary putting to death of the guilty. That parents of relatives of the victims want this death, by natural reaction of hurt human beings, I can conceive it, I can understand

it. But it is a human, natural reaction. And all the historical progress of justice has consisted into going beyond private revenge. And how to go beyond it except by first refusing the “an eye for an eye” principle?

The truth is that, in the deepest motivations of retention of capital punishment, one finds, most often hushed up, the temptation of elimination. What appears unbearable for many is less the life of the criminal in jail than the fear he might repeat offence some day. And they think that the only guarantee, to this regard, is that the criminal be put to death out of precaution.

So, according to this conception, justice would kill out of prudence rather than out of revenge. Beyond this expiation justice would thus appear elimination justice, guillotine behind balance. The criminal must die just because, this way, he won’t repeat offence. And everything seems so easy, and everything looks so right!

But when one accepts, or when one advocatesfor, elimination justice, in the name of justice, one must be fully aware of which logic one enters into. To be acceptable, even for its advocates, a justice that kills a criminal must kill with full knowledge of the facts. Our justice, and it’s its honour, does not kill lunatics. But it isn’t able to definitely identify them, and

for this, in the judicial reality, one leaves it up to psychiatric expertise, the most chancy, the most uncertain of all. If the psychiatric verdict is favourable to the criminal, he shall be spared.

Society will accept the risk he represents and no one would get indignant about it. But

if the psychiatric verdict is unfavourable to him, he shall be executed. When they accept elimination justice, political leaders must measure in which historical logic they enter.

I don’t talk about those societies that eliminate criminals as well as lunatics, political opponents and those they think could "pollute" the social body. No, I strictly refer to those countries that live in democracy. Secret racism is buried, crouched down at the very heart of elimination justice. If, in 1972, the Supreme Court of the United States favoured abolition, it was primarily because it had noticed that 60% of the death row inmates were Blacks, whereas they only represented 12% of the population.

What a dizzy for a man of justice!

I lower my voice and turn to you all to recall that, even in France, on 36 definitive death sentences pronounced since 1945, there are 9 foreigners, that is 25%, while they only account for 8% of the population; among them 5 North Africans, while they only account for 2% of the population.

Since 1965, among the 9 death row inmates who have been executed, there are 4 foreigners, including 3 North Africans. Were their crimes more heinous than others’, or did they seem more serious because their authors, at that time, were secretly horrifying society? It’s a question, just a question, but it is so insistent and so haunting that only abolition can put an end to such a question that hits us with such cruelty.

Abolition is eventually, indeed, a fundamental choice, a certain conception of humanity and of justice. Those who want a justice that kills, are motivated by a double conviction: that there are men who are totally guilty, that is to say men totally responsible for their acts, and that there can be a justice certain of its infallibility, to the point of saying that this one can live and that one shall die.

At this age of my life, both of those assertions seem equally erroneous to me. As terrible, as obnoxious as their acts can be, there are no men on this earth whose guilt would be total and about whom one should totally despair. As prudent as justice can be, as moderated and anguished as the women and men who judge can be, justice remains human, thus fallible.

And I don’t only talk about absolute miscarriage of justice, when, after an execution, it appears, as it can still happen, that the death row inmate was innocent and that a whole society – that is, all of us -, in the name of which the sentence was pronounced, thus becomes collectively guilty since its justice enables the supreme injustice.

I talk also about the incertitude and the contradiction between pronounced sentences, when the same convicts, sentenced to death a first time, whose sentences are cancelled for a legal

irregularity, are again judged and, though the facts remain the same, escape, this time, from death, as if the life of a man was determined by the fate of a court clerk’s pen mistake. Or about certain convicts who, for less serious crimes, will be executed, while others, more guilty, will manage to save their heads thanks to the passion of the hearings, the atmosphere or

the rage of someone or other.

This kind of judicial lottery, whatever the difficulty one would feel for this word when the life of a woman or of a man is at stake, is intolerable. The highest magistrate of France, M. Aydalot, at the end of a long career, totally dedicated to justice and, for most of his activity, to the public prosecutor’s department, said that, as it was randomly implemented, capital punishment had become, for him, as a magistrate, unbearable.

For those of us who believe in God, He alone has the power to choose the moment of our death. For all the abolitionists, it is impossible to recognise human justice with this power of death, because they know it is fallible.

The choice that is lying in front of your consciences is thus clear: either our society refuses a justice that kills and accepts, in the name of its fundamental values – those that made it great and respected among all -, to take on the lives of those, lunatics or criminals, or both together, that horrify it, and that is the choice of abolition; or this society believes, in spite of the experience of centuries, it can make crime disappear with the criminal, and that’s elimination.

This elimination justice, this justice of anguish and death, decided with its margin of hazard, we refuse it. We refuse it because it is, for us, anti-justice, because it is passion and fear prevailing over reason and humanity. I have told the essentials about the spirit and the inspiration of this

important bill. Raymond Forni, a while ago, exposed its main guidelines.

They are easy and precise.

Because abolition is a moral choice, it is important to take a clear decision. The Government, thus, asks you vote the abolition of capital punishment without accompanying it by any restriction or reserve. There is no doubt that amendments will be submitted to restrain the scope of abolition and exclude therefrom diverse categories of crimes. I understand

the inspiration of those amendments but the Government will ask you reject them.

First, because the expression "abolish except for heinous crimes" only means, in reality, a statement in favour of capital punishment. In judicial reality, nobody incurs capital punishment except for heinous crimes. It is better, in such a case, to avoid style conveniences and declare oneself in favour of capital punishment. (Applause from socialist benches.)

As far as suggestions to shape the scope of abolition with regard to the quality of the victims, especially with regard to their particular weakness or the greatest risks they incur, the Government will also ask you reject them, in spite of the generosity that motivates them.

Those exclusions ignore an obvious fact: all the victims, and I stress the word “all”, are pitiable and deserve the same compassion. No doubt that, for each of us, the death of a child or of an elderly arouses more easily emotion than the death of a thirty-year-old woman or of a mature man with responsibilities, but, in human reality, both are equally painful and any discrimination to this regard would create injustice!

Regarding policemen or prison personals, whose representative organisations require the retention of capital punishment against those who would make an

attempt on the lives of their members

[transcript cuts out]