January 1963, New York City, New York, USA

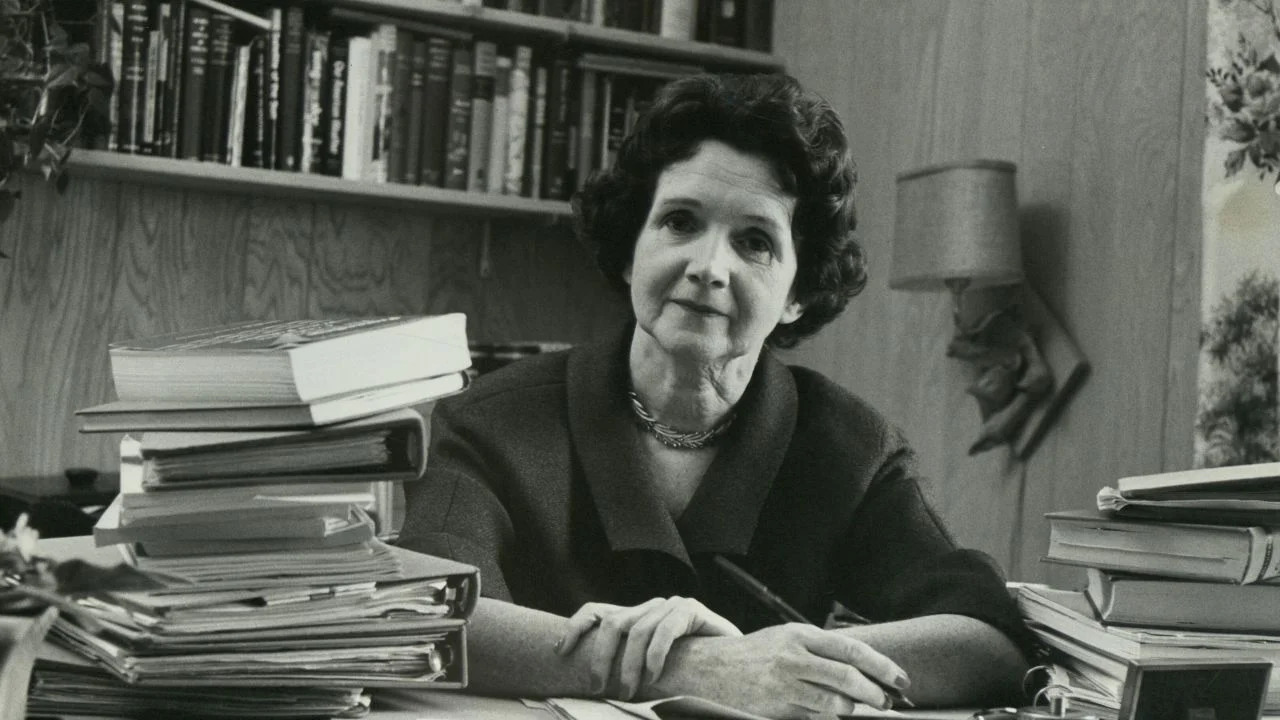

Rachel Carson was a pioneer, a marine biologist who was one of the first activist scientists in American history. Silent Spring is her most famous book. She died in 1964,. Many regard her as the inspiration for the modern environmental movement.

I am particularly glad to have this opportunity to speak to you. Ever since, ten years ago, you honored me with your Frances Hutchinson medal, I have felt very close to The Garden Club of America. And I should like to pay tribute to you for the quality of your work and for the aims and aspirations of your organization. Through your interest in plant life, your fostering of beauty, your alignment with constructive conservation causes, you promote that onward flow of life that is the essence of our world.

This is a time when forces of a very different nature too often prevail – forces careless of life or deliberately destructive of it and of the essential web of living relationships.

My particular concern, as you know, is with the reckless use of chemicals so unselective in their action that they should more appropriately be called biocides rather than pesticides. Not even their most partisan defenders can claim that their toxic effect is limited to insects or rodents or weeds or whatever the target may be.

The battle for a sane policy for controlling unwanted species will be a long and difficult one. The publication of Silent Spring was neither the beginning nor the end of that struggle. I think, however, that it is moving into a new phase, and I would like to assess with you some of the progress that has been made and take a look at the nature of the struggle that lies before us.

We should be very clear about what our cause is. What do we oppose? What do we stand for? If you read some of my industry-oriented reviewers you will think that I am opposed to any efforts to control insects or other organisms. This, of course, is not my position and I am sure it is not that of The Garden Club of America. We differ from the promoters of biocides chiefly in the means we advocate, rather than the end to be attained.

It is my conviction that if we automatically call in the spray planes or reach for the aerosol bomb when we have an insect problem we are resorting to crude methods of a rather low scientific order. We are being particularly unscientific when we fail to press forward with research that will give us the new kind of weapons we need. Some such weapons now exist – brilliant and imaginative prototypes of what I trust will be the insect control methods of the future. But we need many more, and we need to make better use of those we have. Research men of the Department of Agriculture have told me privately that some of the measures they have developed and tested and turned over to the insect control branch have been quietly put on the shelf.

I criticize the present heavy reliance upon biocides on several grounds: First, on the grounds of their inefficiency. I have here some comparative figures on the toll taken of our crops by insects before and after the DDT era. During the first half of this century, crop loss due to insect attack has been estimated by a leading entomologist at 10 percent a year. It is startling to find, then, that the National Academy of Science last year placed the present crop loss at 25 percent a year. If the percentage of crop loss is increasing at this rate, even as the use of modern insecticides increases, surely something is wrong with the methods used! I would remind you that a non-chemical method gave 100 percent control of the screwworm fly – a degree of success no chemical has ever achieved.

Chemical controls are inefficient also because as now used they promote resistance among insects. The number of insect species resistant to one or more groups of insecticides has risen from about a dozen in pre-DDT days to nearly 150 today. This is a very serious problem, threatening, as it does, greatly impaired control.

Another measure of inefficiency is the fact that chemicals often provoke resurgences of the very insect they seek to control, because they have killed off its natural controls. Or they cause some other organism suddenly to rise to nuisance status: spider mites, once relatively innocuous, have become a worldwide pest since the advent of DDT.

My other reasons for believing we must turn to other methods of controlling insects have been set forth in detail in Silent Spring and I shall not take time to discuss them now. Obviously, it will take time to revolutionize our methods of insect and weed control to the point where dangerous chemicals are minimized. Meanwhile, there is much that can be done to bring about some immediate improvement in the situation through better procedures and controls.

In looking at the pesticide situation today, the most hopeful sign is an awakening of strong public interest and concern. People are beginning to ask questions and to insist upon proper answers instead of meekly acquiescing in whatever spraying programs are proposed. This in itself is a wholesome thing.

There is increasing demand for better legislative control of pesticides. The state of Massachusetts has already set up a Pesticide Board with actual authority. This Board has taken a very necessary step by requiring the licensing of anyone proposing to carry out aerial spraying. Incredible though it may seem, before this was done anyone who had money to hire an airplane could spray where and when he pleased. I am told that the state of Connecticut is now planning an official investigation of spraying practices. And of course on a national scale, the President last summer directed his science advisor to set up a committee of scientists to review the whole matter of the government’s activities in this field.

Citizens groups, too, are becoming active. For example, the Pennsylvania Federation of Women’s Clubs recently set up a program to protect the public from the menace of poisons in the environment – a program based on education and promotion of legislation. The National Audubon Society has advocated a 5-point action program involving both state and federal agencies. The North American Wildlife Conference this year will devote an important part of its program to the problem of pesticides. All these developments will serve to keep public attention focused on the problem.

I was amused recently to read a bit of wishful thinking in one of the trade magazines. Industry “can take heart,” it said, “from the fact that the main impact of the book (i.e., Silent Spring) will occur in the late fall and winter – seasons when consumers are not normally active buyers of insecticides [ … ] it is fairly safe to hope that by March or April Silent Spring no longer will be an interesting conversational subject.”

If the tone of my mail from readers is any guide, and if the movements that have already been launched gain the expected momentum, this is one prediction that will not come true.

This is not to say that we can afford to be complacent. Although the attitude of the public is showing a refreshing change, there is very little evidence of any reform in spraying practices. Very toxic materials are being applied with solemn official assurances that they will harm neither man nor beast. When wildlife losses are later reported, the same officials deny the evidence or declare the animals must have died from “something else.”

Exactly this pattern of events is occurring in a number of areas now. For example, a newspaper in East St. Louis, Illinois, describes the death of several hundred rabbits, quail and songbirds in areas treated with pellets of the insecticide, dieldrin. One area involved was, ironically, a “game preserve.” This was part of a program of Japanese beetle control.

The procedures seem to be the same as those I described in Silent Spring, referring to another Illinois community, Sheldon. At Sheldon the destruction of many birds and small mammals amounted almost to annihilation. Yet an Illinois Agriculture official is now quoted as saying dieldrin has no serious effect on animal life.

A significant case history is shaping up now in Norfolk, Virginia. The chemical is the very toxic dieldrin, the target the white fringed beetle, which attacks some farm crops. This situation has several especially interesting features. One is the evident desire of the state agriculture officials to carry out the program with as little advance discussion as possible. When the Outdoor Edition of the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot “broke” the story, he reported that officials refused comment on their plans. The Norfolk health officer offered reassuring statements to the public on the grounds that the method of application guaranteed safety: The poison would be injected into the ground by a machine that drills holes in the soil. “A child would have to eat the roots of the grass to get the poison” he is quoted as saying.

However, alert reporters soon proved these assurances to be without foundation. The actual method of application was to be by seeders, blowers and helicopters: the same type of procedure that in Illinois wiped out robins, brown thrashers and meadowlarks, killed sheep in the pastures, and contaminated the forage so that cows gave milk containing poison.

Yet at a hearing of sorts concerned Norfolk citizens were told merely that the State’s Department of Agriculture was committed to the program and that it would therefore be carried out.

The fundamental wrong is the authoritarian control that has been vested in the agricultural agencies. There are, after all, many different interests involved: there are problems of water pollution, of soil pollution, of wildlife protection, of public health. Yet the matter is approached as if the agricultural interest were the supreme, or indeed the only one.

It seems to me clear that all such problems should be resolved by a conference of representatives of all the interests involved.

I wonder whether citizens would not do well to be guided by the strong hint given by the Court of Appeals reviewing the so-called DDT case of the Long Island citizens a few years ago.

This group sought an injunction to protect them from a repetition of the gypsy moth spraying. The lower court refused the injunction and the United States Court of Appeals sustained this ruling on the grounds that the spraying had already taken place and could not be enjoined. However, the court made a very significant comment that seems to have been largely overlooked. Regarding the possibility of a repetition of the Long Island spraying, the judges made this significant general comment: “… out would seem well to point out the advisability for a district court, faced with a claim concerning aerial spraying or any other program which may cause inconvenience and damage as widespread as this 1957 spraying appears to have caused, to inquire closely into the methods and safeguards of any proposed procedures so that incidents of the seemingly unnecessary and unfortunate nature here disclosed, may be reduced to a minimum, assuming, of course, that the government will have shown such a program to be required in the public interest.”

Here the United States Court of Appeals spelled out a procedure whereby citizens may seek relief in the courts from unnecessary, unwise or carelessly executed programs. I hope it will be put to the test in as many situations as possible.

If we are ever to find our way out of the present deplorable situation, we must remain vigilant, we must continue to challenge and to question, we must insist that the burden of proof is on those who would use these chemicals to prove the procedures are safe.

Above all, we must not be deceived by the enormous stream of propaganda that is issuing from the pesticide manufacturers and from industry-related – although ostensibly independent – organizations. There is already a large volume of handouts openly sponsored by the manufacturers. There are other packets of material being issued by some of the state agricultural colleges, as well as by certain organizations whose industry connections are concealed behind a scientific front. This material is going to writers, editors, professional people, and other leaders of opinion.

It is characteristic of this material that it deals in generalities, unsupported by documentation. In its claims for safety to human beings, it ignores the fact that we are engaged in a grim experiment never before attempted. We are subjecting whole populations to exposure to chemicals which animal experiments have proved to be extremely poisonous and in many cases cumulative in their effect. These exposures now begin at or before birth. No one knows what the result will be, because we have no previous experience to guide us.

Let us hope it will not take the equivalent of another thalidomide tragedy to shock us into full awareness of the hazard. Indeed, something almost as shocking has already occurred – a few months ago we were all shocked by newspaper accounts of the tragedy of the Turkish children who have developed a horrid disease through use of an agricultural chemical. To be sure, the use was unintended. The poisoning had been continuing over a period of some seven years, unknown to most of us. What made it newsworthy in 1962 was the fact that a scientist gave a public report on it.

A disease known as toxic porphyria has turned some 5,000 Turkish children into hairy, monkey-faced beings. The skin becomes sensitive to light and is blotched and blistered. Thick hair covers much of the face and arms. The victims have also suffered severe liver damage. Several hundred such cases were noticed in 1955. Five years later, when a South African physician visited Turkey to study the disease, he found 5,000 victims. The cause was traced to seed wheat which had been treated with a chemical fungicide called hexachlorobenzene. The seed, intended for planting, had instead been ground into flour for bread by the hungry people. Recovery of the victims is slow, and indeed worse may be in store for them. Dr. W. C. Hueper, a specialist on environmental cancer, tells me there is a strong likelihood these unfortunate children may ultimately develop liver cancer.

“This could not happen here,” you might easily think.

It would surprise you, then, to know that the use of poisoned seed in our own country is a matter of present concern by the Food and Drug Administration. In recent years there has been a sharp increase in the treatment of seed with chemical fungicides and insecticides of a highly poisonous nature. Two years ago an official of the Food and Drug Administration told me of that agency’s fear that treated grain left over at the end of a growing season was finding its way into food channels.

Now, on last October 27, the Food and Drug Administration proposed that all treated food grain seeds be brightly colored so as to be easily distinguishable from untreated seeds or grain intended as food for human beings or livestock. The Food and Drug Administration reported: “FDA has encountered many shipments of wheat, corn, oats, rye, barley, sorghum, and alfalfa seed in which stocks of treated seed left over after the planting seasons have been mixed with grains and sent to market for food or feed use. Injury to livestock is known to have occurred.

“Numerous federal court seizure actions have been taken against lots of such mixed grains on charges they were adulterated with a poisonous substance. Criminal cases have been brought against some of the shipping firms and individuals.

“Most buyers and users of grains do not have the facilities or scientific equipment to detect the presence of small amounts of treated seed grains if the treated seed is not colored. The FDA proposal would require that all treated seed be colored in sharp contrast to the natural color of the seed, and that the color be so applied that it could not readily be removed. The buyer could then easily detect a mixture containing treated seed grain, and reject the lot.”

I understood, however, that objection has been made by some segments of the industry and that this very desirable and necessary requirement may be delayed. This is a specific example of the kind of situation requiring public vigilance and public demand for correction of abuses.

The way is not made easy for those who would defend the public interest. In fact, a new obstacle has recently been created, and a new advantage has been given to those who seek to block remedial legislation. I refer to the income tax bill which becomes effective this year. The bill contains a little known provision which permits certain lobbying expenses to be considered a business expense deduction. It means, to cite a specific example, that the chemical industry may now work at bargain rates to thwart future attempts at regulation.

But what of the nonprofit organizations such as the Garden Clubs, the Audubon Societies and all other such tax-exempt groups? Under existing laws they stand to lose their tax-exempt status if they devote any “substantial” part of their activities to attempts to influence legislation. The word “substantial” needs to be defined. In practice, even an effort involving less than 5 percent of an organization’s activity has been ruled sufficient to cause loss of the tax-exempt status.

What happens, then, when the public interest is pitted against large commercial interests? Those organizations wishing to plead for protection of the public interest do so under the peril of losing the tax-exempt status so necessary to their existence. The industry wishing to pursue its course without legal restraint is now actually subsidized in its efforts.

This is a situation which the Garden Club, and similar organizations, within their legal limitations, might well attempt to remedy.

There are other disturbing factors which I can only suggest. One is the growing interrelations between professional organizations and industry, and between science and industry. For example, the American Medical Association, through its newspaper, has just referred physicians to a pesticide trade association for information to help them answer patients’ questions about the effects of pesticides on man. I would like to see physicians referred to authoritative scientific or medical literature – not to a trade organization whose business it is to promote the sale of pesticides.

We see scientific societies acknowledging as “sustaining associates” a dozen or more giants of a related industry. When the scientific organization speaks, whose voice do we hear – that of science or of the sustaining industry? The public assumes it is hearing the voice of science.

Another cause of concern is the increasing size and number of industry grants to the universities. On first thought, such support of education seems desirable, but on reflection we see that this does not make for unbiased research – it does not promote a truly scientific spirit. To an increasing extent, the man who brings the largest grants to his university becomes an untouchable, with whom even the University president and trustees do not argue.

These are large problems and there is no easy solution. But the problem must be faced.

As you listen to the present controversy about pesticides, I recommend that you ask yourself – Who speaks? – And Why?