16 May 2016, Belvoir Street Theatre, Sydney, Australia

First published on Belvoir website. Thanks for permission to re-post.

Good evening, everyone.

I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal people who are the traditional custodians of this land on which we stand. I would also like to pay respect to the elders, past and present of the Eora nation, and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait people present here today.

My name is Kate Mulvany. I am an actor. A playwright. A former recipient of the Philip Parsons Award. And an unapologetic lover of the Australian arts.

When I was first asked a couple of months ago to give this lecture, I ruminated long and hard as to where to even begin. The arts is an arena of stories, politics and personalities that all deserve a good lecture. But so much has happened since I was first asked to speak. In the past week, our industry has found itself in a state of enforced shock. 62 arts companies have been left with an unknown future. Important companies that provide so much art and heart to a diverse range of communities across Australia. Companies that I can honestly say I wouldn’t be here without, and nor would so many of our artists. Our community has been passionately vocal in the past week, not just in support of the companies in trouble, but for the Australia Council, who has been forced to make some incredibly heartbreaking decisions on behalf of their peers.

But despite everything that has happened to our industry in the past week, I am not going to speak about the specifics of any funding decisions. Nor am I going to delve into the ongoing issue of gender parity on and off our stages. Cultural diversity in our storytelling and team gathering is a subject intensely close to my heart, and a conversation that I will always want to have. But that is also not my focus today.

Rather, I feel all of these – and more – come under the banner I have rather unexpectedly controversially selected.

Love.

You heard me.

Love.

When I first revealed to the organisers of this event that I wanted to speak about the love of my industry, I was told that the subject was not provocative enough. “The Parsons award is supposed to stir things up”, I was told. I think they wanted blood. And who can blame them, with all that’s going on right now. But the more I asked around, the more I realised – even before the events of the past week – that the members of the arts community did indeed want something a little more affirming this year. Less blame, less politics, and more hope. And I believe there is provocation in positivity. So I have stuck to my guns and love is what I’m going to speak about today. But bear with me, because there is method to my mushy madness.

I am a little different to past Parsons speakers. What I say doesn’t come from a place of leading a company or heading a board. I haven’t written any theatrical anthologies or been in charge of an international arts festival.

I’ve found myself in this industry not so much through my head, but my heart.

I have listened intently to so many lectures past with ravenous ears. And as this is the first time the Parsons lecture has been part of the Sydney Writers Festival, I encourage any of you out there that have never been to one before today to read the Parsons transcripts online at Currency Press. They offer a brilliant look at the Australian theatrical landscape. Katherine Brisbane and John McCallum give incredible personal insights into the extraordinary history of Australian theatre. David Hare talks about why writers must “fabulate” – to “stop anyone else from doing so”. Neil Armfield destroys, with his lazy grin and loud shirts, the politicians that see art like a piece of unwanted fluff on their Armani suits. And speaking of suits, Ralph Myers’ had quite the beef with artists daring to wear them in his lecture from last year.

But today, in this space that I worship – for the theatre is, indeed my church – I want to get embarrassingly emotional. Because yes, I am a writer, but I am also an actor. And when I’m on a stage, I want to speak my truth with all the head, heart and guts I can. And at the heart of what I’ll be speaking about today is that ancient trope that appears in every word of every play, from William Shakespeare to Sarah Kane to Patricia Cornelius to Nakkiah Lui. Love. Love of storytelling. Love of culture. Love of each other. Love of self.

Bit of background. I grew up in country Western Australia. An industry town of mining, fishing, farming. An incredibly diverse community on Yamatji land. Yamatji, Greek, Vietnamese, Italian, African, Nyoongar made up my ten-pound-pom Dad’s soccer team. My adopted family. I was born with cancer so much of my childhood was spent quarantined in hospitals, but when I was lucky enough to get visitors, it was those people who were my storytellers. My Sicilian godparents regaled me with stories of escaping Mussolini’s Italy. Vietnamese schoolfriends narrated their passage to Australia on a leaky boat, hidden under a pile of rotting cabbages. My Bardi aunty spoke softly, sadly, of a massacre up north at Forrest River that she’d survived as a baby. I grew up surrounded by tales of the Batavia mutiny, Dutchmen slaughtered on the shores of my town by a madman who left ghosts in the sandy dunes. And my own story – born with cancer from a poison sprayed in a war six years before I was conceived – was first spoken of in hushed tones in that very hospital ward. 25 years later that hushed story was spoken out loud on this very stage in a play called The Seed that I wrote after winning the Philip Parsons Award. What goes around comes around.

That pediatrics ward… So many stories. So many voices. So many spirits. I found that my time in hospital was a lot easier if I had these stories told to me time and again by my various narrators. When that wasn’t possible, I’d just learn them off by heart and tell them myself. With all the accents. All the gesticulations. All the love. With an audience of stern nurses and tired parents and frail, bald-headed children. Stories just made things better. In that hospital ward, between the ages of 3 and 10, in a country town that didn’t even have a drive-in, let alone a cultural precinct, I discovered the magic of theatre. That an empty space can become anything you want it to be. A bed can become a train. A drip can become a giraffe. A father can become a princess. A nurse can become a nemesis. And even in a hospital ward, there is an audience to be found, even if they are just stuffed toys sitting on a window ledge.

By running wild with our imaginations, that oncology ward became bearable. Me and my unlikely band of castmates learnt to listen to one another with empathetic ears. We got to divulge our fears and our dreams. We got to laugh. Cry. Play. Question our mortality. Celebrate life. We didn’t all make it out of that ward, but at least we got to tell our stories. (Because even a child of three has a story.) And it did change our world. I truly believe that those shared experiences saved my life. And when I was better, I decided I wanted more of that. I wanted to keep sharing stories. To understand the narratives of the people around me. To chronicle them. Honour them. Celebrate life. Embrace existence.

Life since those early hospital days has delivered me into the Australian arts industry – something I am so grateful for. Now in my 20th professional year as an actor and writer, I have found myself surrounded by the hearts and minds of the most extraordinary and diverse and inspiring people. Artists that want to challenge not just themselves, but the world around them. Artists that question our place as a nation, that investigate our individual roles in our national story. Artists that aren’t afraid to strip bare their own psyche in order to let audiences see themselves. Artists that fuck with form, demand and command, that say no to the traditional stilt of the British theatre and no to the garish Broadway glitz and glamour, and have instead forged for themselves a national conversation on the stage between Australian artists and audience. Stories that are worthy of their place, not just on Australian stages, but amongst the international canon of theatre. From On Our Selection to Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, Cloudstreet, Bangarra’s Corroboree, Simon Stone’s Wild Duck, Yirra Yaakin’s Noongar Shakespearean Sonnets for the Globe Theatre to Lally Katz’s Stories I Want to Tell You in Person. From Dame Joan Sutherland to Judy Davis, Barry Humphries to Barry Kosky, Errol Flynn to Wayne Blair. Jacki Weaver to Meow Meow. All of these people and productions started on the Australian stage and have gone on to international acclaim. Worthy stories from profound storytellers. Our national narratives woven into a larger international artistic portrait.

So when I hear my industry derided as somehow unworthy of support, I call bullshit. When politicians who in my twenty years as a member of the arts community I have never seen at the Old Fitzroy or The Blue Room or Red Stitch reduce our industry to whether we meet their version of “excellence”, I call bullshit. When we have had a governed Sword of Damacles hanging over our industry for a full year – a YEAR of not knowing whether the company that has been lovingly nurtured, in some cases, for decades, will be around even for its next season – I call bullshit. And when I see my fellow artists – normally so strong and resilient and brave – suffering, because it has been inferred that their life work is worthless, I call bullshit.

Because this is what’s happening. A toll is being taken. It’s a devastating repercussion of the past year. And here’s an example of the domino effect. Recently, I was on a panel at an event that was talking all things theatre. Namely, women in theatre. It was a beautiful night, filled with invigorating and important conversation. So I was stunned on my way to the bathroom after the event to find a young woman, no older than 20, crying alone in a dark corner. When I asked her if she was ok, she said, “I just don’t know how to do this.” She said, “If the people in that room are scared about where the industry is headed, then what hope is there for someone like me? My whole life I’ve wanted to be a writer, but everything I encounter lately seems to be saying I’m not worthy.” She told me she’d tried to contact me on Facebook. She’d sent me a message but “it probably went through to your other message folder.” She then went on to illuminate me about the other message folders on Facebook that are often filled with Spam, but also contain personal correspondence from strangers. I got home that night to find over 30 messages from young Australian artists from a vast array of backgrounds and cultures asking pretty much the same thing – “What do I do? Where do I go? Who do I talk to? It all seems too hard.”

And this broke my heart. Because I didn’t have an answer. In the arts industry, we can present the delicacies of human psychology on a stage, but when it comes to our own fragility, we close up. I’m not sure why this is. Maybe because we don’t want to be seen as any more “precious” than we are so often misrepresented. Maybe because we feel we purge enough through our work, and that is somehow all the therapy we need. Maybe because we feel we need to hang onto that frailty in order to be artists in the first place. But I was filled with fear, that whoever this girl was – and she could well be the next Caryl Churchill, Debra Oswald or Young Jean Lee – we might miss out on what she has to say.

The Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance and the Sydney University Theatre and Performance Department recently released the results of their “Australian Actors Wellbeing Study”. Although it was a study of actors, similar results have been reported in all areas of the arts. The MEAA reported in the artists they surveyed “significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress than Australian adults in general.” Twice that of the general population, in fact. Much of the fear expressed by artists comes from the fact that now, more than ever, our work and our worth is being diminished. And when we dare to start a dialogue about this, we are often berated for it by others who don’t understand what it is to be an artist. We are often portrayed us as a bunch of whining, bleeding hearts who are crying poor. “What do you offer the world?” is often sneered at us in opinion columns, or on messageboards. “Do you save lives? Do you create wealth? Would we even notice if you were gone?”

My answer to all those questions is yes. A resounding “Fuck, yes”. The telling and sharing of stories does indeed save lives. It saved mine. I have been involved in and witnessed plays that have spoken out about issues that are all but ignored by those same questioning naysayers, those same pompous politicians who rarely bother to turn up. I’ve seen people wait in the foyer afterwards to say to the artists involved, “Thank you for giving me a voice when no-one else does.” I still get correspondence about The Seed from Vietnam Veterans and their children who believe the play changed them. I would venture to say Nakkiah Lui would have had the same response for Kill the Messenger. Tommy Murphy for Holding the Man. Angus Cerini for The Bleeding Tree. Yes. Art can save lives. Not with a scalpel. Or medicine. Or money. But with shared honesty, empathy and imagination.

Yes, we do create wealth. According to the Australia Council, the cultural sector of our working nation contributed $50 billion to Australia’s GDP in 2012–13. We give back a hell of a lot more than we receive. And yet that kind of wealth is not something we shout from the rooftops in this business. Because we know that wealth is not always monetary. What wealth is is an abundance of riches. And we have such riches in the cultural chronicles of our country and its people. We have the oldest storytellers in the world here. At least 50,000 years of stories. There’s as much wealth to be gained in those stories as in any mine, farm, any shipload of sheep. Our greatest wealth comes from our elders. From those lessons passed from one generation to another, shared amongst cultures. That’s wealth. And yes. We do create it, us artists. Because we’re the ones that dare to chronicle those stories, perform them, honour them, on behalf of the vast array of communities that make up this country.

So yes, you would notice us if we were gone. Maybe not for a little while, but I’ll get to that later.

Please don’t get me wrong. I know there are bigger issues. Our country’s political practices at the moment are nothing less than shameful. Our moral compass has been seemingly smashed. People are suffering in enforced silenced. Our indigenous communities. Our refugees. Our gay friends who simply want the right to marry. With all this going on I know some people may find it insulting to bring up the welfare of the arts community. But because it’s the arts community that historically has the guts to speak out on these issues, I feel like it’s worth talking about. Like so many of the characters and narratives that exist in society, there’s only so many times you can be told, “You don’t meet our model of excellence” before you start to get worn down and a very dark fear kicks in. Our community suffers. Our families suffer. Our culture suffers. That moral compass spins out of control, unattended. And when these things happen, our stories disappear – sometimes tragically.

And that’s exactly what they want, those people that flick the first domino. They want us to shut up. They don’t want now explored and challenged. Because they know it’s a time of societal shame. And they don’t want their legacy tarnished by the chronicling of truth. And so we’re being silenced.

But there is a solution to this enforced fear, because what we do have…is each other.

You see, I see this thing called “the arts” not as an industry so much, but as a house. A big rambling, knockabout house worthy of a Winton staging. Its paint is peeling, the floorboards are splintered, but its foundations are good. Strong. Resilient. This house has nails hammered into it by Steele Rudd. It’s been wallpapered by George Ogilvie. Dorothy Hewett has tended the garden. Philip Parsons and Katherine Brisbane have lovingly set up its library. It has the beating heart of the oldest living population in the world and the rooms ring with the languages of countless cultures.

This is a house of many, many, many rooms. And many many many tenants.

Each level of the house is accommodated by several companies. There used to be more to a floor, but as I’ve mentioned, of late there’s been some unfortunate evictions. This leaves the remaining tenants with more space around them, perhaps, but ultimately the house just doesn’t feel complete. The rambunctious, provocative voices that used to ring vibrantly from the middle and ground floors are no longer there, and the house feels different because of it.

Now, there is a danger in such an environment, because fear breeds fear. There’s the risk that the tenants will start to tiptoe around one another. Doors will be shut fast. Curtains drawn tight. Rooms darkened. No fresh air will filter down the hallways. The remaining tenants will become secretive. Argumentative. Ruthless.

I am currently in the position of working for several of Australia’s arts companies in various ways, from writer to actor to board member. I move from room to room in the theatrical house, between levels, upstairs and downstairs. I am in awe of all of them and have become acutely aware of how hard it is to keep a company afloat. To manage a team. To bring in an audience. But I can’t help but notice that the tightening fist around our industry at the moment is causing us to close down in more ways than one. Companies are becoming shrewd – and not in a good way. There seems to be an unhealthy competitiveness. A fear that there is not enough to go around, so all resources must be protected fiercely. And that’s probably what they want us to do. But we’re better than that, in this house.

If we were to look at our current predicament as a theatre production, then we can see that each of us has a part to play. We are a cast and crew that needs to pull together to keep the show going.

I’m going to go through each member of the house now, and offer no solutions – just suggestions – on how they can, to borrow from Alexander Pope, act well their part, for there all honour lies.

Companies on the top floor.

I’m incredibly heartened by the current group of artistic directors and Festival heads in this country. What we have at the moment are people who are proud of the heritage of Australian theatre and invigorated by its future potential. They are doing their best to make amends for past failings in our community. They are slowly but surely starting to embrace gender parity. Colour-blind casting. They are optimistic, intelligent, generous human beings.

What they need to do now, more than ever, is work together. When Brandis brandished his sword, so many wonderful people of influence in our industry – from companies that were “safe” from the cuts – stepped forward and spoke up without hesitation for their colleagues who were at risk of very soon finding themselves without a job. It was a glorious display of camaraderie between companies. But it should have been more widespread. The silence from certain individuals and companies in the industry was deafening.

I was flummoxed around that time when a prominent Sydney mainstage associate told me that they didn’t go and see plays at the Bondi Pavilion or the Old Fitzroy because they were “so far away”. The next week, that same person went to Europe to catch the latest Schaubuhne production. They missed a wonderful season of new Australian playwriting at the now defunct Pav. They missed their chance to see new writers. New actors. New directors. New stories. Would’ve cost them 15 bucks. The same person lamented to me on their return that they were trying to think of the right person for a role, but “don’t know anyone out there that fits the bill…” I gave them the Pav program.

We can’t afford to let this sort of complacent elitism happen. We need to keep those voices on the ground floor and middle floors ringing out with Australian stories or our much-loved house will collapse beneath us. If they’ve been evicted from the middle and ground floors, then you’ve got to invite them upstairs. Now more than ever.

We need to move from a hierarchical view of our industry to a heterarchical view. To quote Chantal Bilodeau in her amazing essay Why I’m Breaking Up With Aristotle, “What we need today is a conscious use of dramatic structure in service of societal change. The hierarchical pyramidal worldview is based on values that promote competition, control and a sense of scarcity– that there isn’t enough to go around. And since we have to fight for everything, there will always be winners and losers. The heterarchical worldview, on the other hand, promotes innovation, collaboration and creativity. It works with the assumption of abundance – that there is enough. We just need to look for it and distribute it more equitably.”

I’m so thrilled that in the past year, some companies are taking a more heterarchical view. I mention a couple now, not because they are the only ones, but they are the ones whose workings I have been most privy to. Bell Shakespeare is using their philanthropic support networks to fund Australian playwrights. Of all the companies in Australia, Bell Shakespeare is probably the company that has the most right NOT to do this, given their loyalty to one particular writer. But they have chosen to distribute their precious resources to not one, but two Australian playwrights a year on an overlapping two-year tenure. These playwrights, through Bell’s relationship with the Intersticia Foundation, are given a desk. A computer. Dramaturgical and creative assistance. Actors to workshop their play with. Space and time to write whatever they damn well like – even if it’s for another company. The writers are embraced as a valued team member and included in all administrative matters. As they write, they are privy to the world of theatre business, of the effort that goes on behind the scenes of every production. From marketing to education to accounting – they are included and embraced. As a current Intersticia fellow – alongside Jada Alberts – I’m astounded by the generosity of this “sharing of abundance” and I hope so much that more companies and philanthropists take up this model of heterarchical thought. Bell is also currently involved in a co-production with Griffin Theatre Company so that in these uncertain times, both companies can continue to present satisfying programs to their audiences, but also share audiences for the first time. Innovation. Collaboration. Creativity. More of this, please, those of you on the top floor of the house – let’s see our opera companies collaborate with our indigenous companies, ballet alongside youth theatre. Let’s find a crazy fit. By opening your doors of communication to artists who have been left out in the cold, you will see your audiences introduced to new stories, and you will see new audiences in your auditoriums. You will see new artists at work. New brains. New bodies. New genres. A wondrous artistic alliance.

I can’t tell you enough the impact this kind of inclusion has on an artist. At a time when so many Australian artists are being told they are below par, we need our companies to engage more in this kind of open-hearted, collaborative risk.

Speaking of risk, let’s talk about Australian playwriting.

There used to be a time a few years ago that on the rare occasion an Australian writer was invited into a theatre company for a meeting with a literary associate or an artistic director, they were asked, “What do you want to write?”

Over the past few years, if they are invited in for a cuppa at all, this has become, “We want you to adapt this.” I don’t deny it’s wonderful seeing fresh looks at classic works. Or of popular novels. I don’t deny that these adaptations of classics can still move a modern audience who are looking at it through millennial eyes. However, what canon are we leaving behind? In 5, 10, 50, 100 years, what are we going to have to show for ourselves? At a time when so many political, social, cultural and moral upheavals make up our everyday life in Australia, what are we going to have to show for it? What groundbreaking insight can we share? What lessons can we pass on? What are they going to know about us, here and now, if we’re just retelling old tales that come from another time and place? Adaptations are wonderful, and there are plenty of novels that do deserve a staging, that make for a wonderful night in the theatre. I’ve been part of them and loved every second. But I want to set a challenge for every literary sector on every floor of the theatrical house – when you invite a writer in for a meeting – and please do that more, don’t just rely on who enters your competitions, make time to meet them face to face, Skype them if they live in rural areas – for every adaptation you ask of a writer, ask them what else they’ve got inside their own heart, their own head, their own gut, their own cultural history. Don’t tell them what you want them to adapt. Ask them what they want to say. I guarantee you, they will have plenty of things for you and your audience. The map of our cultural legacy will be all the richer for it. To hark back to that snide question, “Would we notice if you weren’t around?” No, not if we leave no trail of ourselves. So let’s start dropping breadcrumbs now so that future generations can enjoy the gingerbread house.

Companies. Act well your part, for there honour lies.

Okay. Now that we’re talking about them, let’s visit those other tenants in the Australian theatrical house. The writers. They are usually found either scribbling wildly in dark corners, or in the kitchen, slightly dazed, making their 14th cup of Liptons. They are either very quiet or audaciously loud. They have been told over and over and again that they don’t know what they’re saying, that they are unstageable, that their words don’t put bums on seats – but they have time and again proven all that to be absolute bullshit.

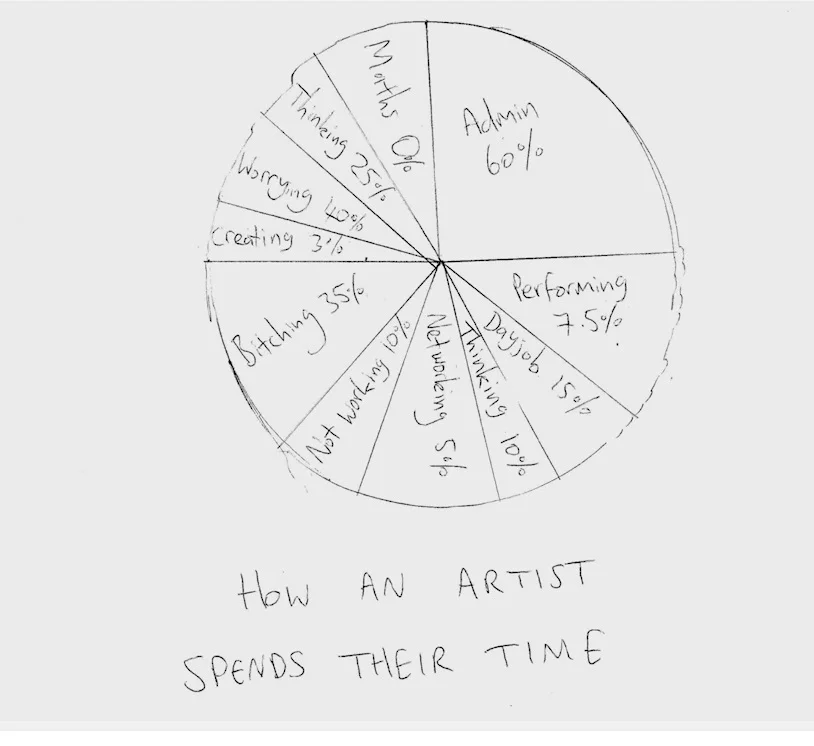

Writers. Keep writing, please. I know it’s hard. I know it’s exhausting. I know that for every moment of success there are 20 rejections. I have not just a bottom drawer of unproduced plays but an entire IKEA filing cabinet. In my time as a playwright, I have only received personal development funding once. $7,500 to see me through a year. As much as I appreciated that money, I learned very quickly that if I wanted to write, I had to self-fund. So for 15 years, when I haven’t been acting or writing, like many other artists, I have had another job that I call my “funding body”. I audio-describe for the visually impaired and caption for the deaf. It’s not glamorous and it doesn’t pay much, it can result in long hours and tight deadlines, but I hang onto it because without it, I’d have to pack everything in. My amazing boss, a man named Javier Arriaga– an avid theatre subscriber who sees several shows a week, from cabaret to musicals, from the Old Fitz to the Lyric – has kept me employed for 15 years. It’s not easy for him to work around my schedule. He has had every right to sack me time and again. But he doesn’t. Because he loves theatre. He appreciates artists. He is the audience we write for. He is the general public I try to speak to with my plays. And he, more than anyone else in my career, has funded me. When no-one else will, or no-one else can, I do, because of people like Javi. This empowering alliance of worlds emboldens me and makes those dark moments of rejection bearable.

But there are other ways to develop your work in dire times if you don’t have a Javi, if the funding doesn’t come. Call on your community. If you have a new play that you need to hear out loud, call on your people. Equity will probably get cross at me for saying this, but fuck it. Ask actors if they are available to come round to your living room – or a spare rehearsal room, companies – and read your play out loud. Invite a director or two. A producer. Any ears available. Buy some pizzas, some wine, hear it played. Pick their brains. Take notes. Just because funding isn’t always available for your work, doesn’t mean it shouldn’t develop and grow. It should and it will. Don’t feel like you’re alone. Call on your community, and community, expect the call.

And in return, support your fellow Australian playwrights. Offer to read. Offer to dramaturg. Offer to mentor. Take emerging playwrights by the hand, now more than ever, and start a dialogue with them. Let them know you are with them. That their stories and words have a place. Go and see the plays of your fellow writers. Don’t expect people to turn up to your shows if you don’t turn up to theirs. Fight for the ideas of your fellow writers as hard as you would fight for your own.

Writers. Act well your part, for there honour lies.

Actors and directors. Often found in the arts house waiting by the telephone, or sound asleep in bed until midday after a night of performance-anxiety-induced insomnia. Acting and directing for stage is a really, really tough gig. That is, when you get the gig, because as we all know, it can be months – years, sometimes – of nothing. Literally nothing.

To these wonderful people, I say, you do act well your part. When I get a play up and I see the actors, directors and creatives that sign on, I am filled with such gratitude. You see, most new Australian works don’t have the luxury of extensive development. A workshop here or there maybe, but intensive, round the table dialogue doesn’t happen until you are in the rehearsal room. It’s terrifying for the writer, who usually ends up redrafting the play on a nightly basis for most of the rehearsal period. So whenever actors and directors and designers and crew sign on for a new Aussie play, we are indebted to them. They are an incredible gift and deserve every success.

But for those creatives with “names”, I ask that you don’t forget us. I would love to see more of our big-name performers returning to the fold from whence they came to support a new Australian play. Not Chekhov. Not Tennessee Williams. Not the latest international commercial blockbuster. New original Australian plays. Because when they reach a certain level, actors, especially, have a lot of influence. They have the power to walk into an artistic director’s office and say, “Hey, I want to do a play. How about that amazing hit on the West End by that old white guy who just got knighted?” Let’s shift that dialogue. I challenge the actors who have that kind of influence, to walk into a company and say, “I want to work with an Australian playwright on a brand new story about what’s happening here, now.” That company will make it happen. That company should make it happen. And that playwright will write you a role to rival any in the theatrical canon. I promise. And you will be giving the gift of your experience not just to that writer but to the entire team of creatives who might not otherwise get to work with you, who might not otherwise get to work at all, because of the damned hierarchical nature of our business.

Actors. Directors. Creatives. Act well your part, for there honour lies.

Agents and managers of said actors, directors and creatives. You may not think so, but you are also part of the artistic house. Not often observed physically, but the effects of your presence can be seen in a footprint by the back shed or crumbs in the kitchen. Agents, please tell your actors if they have been enquired about for a show. I know theatre doesn’t pay well. That you’d rather make your 10% from a three-year television contract or a Hollywood blockbuster. But while you are not telling your actors that they are wanted by a theatrical employer, those same actors are often sitting at home, struggling to pay the bills or support their family, thinking that they are unwanted, thinking that they have failed, especially in this sort of a climate. I cannot tell you how often this happens, that theatre companies and writers and directors are told that an actor is busy, only to find out that that actor was not only available, but desperate to work. Agents. Do not make this situation harder than it needs to be. Take into the account the mental health of your clients. Actors, make sure your agents know that you want to hear about everything when it comes to your journey. And remember that nothing teaches you more about the craft of acting than theatre.

Agents. Act well your part, for there honour lies.

Which brings me to the critics. Yes, critics, you too are part of the arts house. Converging around the bathroom, huddled and whispering. I should say that our Australian critics are going through a crisis of their own at the moment. Newspaper space is as rare as a brand new Australian play, and many theatre critics are losing their jobs, along with so many of their colleagues. You have my sympathy and support. We need critics. You chronicle our chronicles. The best critics show an ongoing enthusiasm for theatre, a passion for new playwriting, an objective eye that takes in their personal response alongside the audience’s, and a wondrous curiosity. I believe most of our critics display these traits in spades. I don’t believe that companies “don’t care what the critics say”. They do. Nothing beats word of mouth, of course, but the role of the critic is an influential one. And so I sincerely ask that you act well your part.

With critical space so rare and social media so virulent, it’s highlighted the fine art of good critiquing. My fear is that the hierarchical model is becoming prevalent in this area too. There seems to be some critics out there competing with a deliberately poison pen, and using nastiness as clickbait, to plant their flag in the already diminished column space.

In the past couple of years, I have read reviews that have commented on the personal lives of performers. I have seen reviewers consistently berate artists that didn’t go to an acting school. One reviewer even compared an actor to a corn kernel in a piece of faeces. And that was him being nice.

This kind of critiquing offers no intelligent insight into the work. Just extreme, calculated malice that can be utterly debilitating. That kind of reviewing seems to be getting more common – particularly online – and it worries me. Because it’s not healthy for either of our industries. Not a single person gets anything from that kind of critiquing – not audiences, not readers, not performers, not companies. Not even the reviewer. I’m not asking for soft focus when critics come and see a play, but I am asking for you to maintain your empathy and intellect when you write about the work of others, especially at this time when it’s amazing any of us can get anything on at all. Keep it above board. Don’t waste column space on sneering asides just to get infamous. Honour your own craft with dignity.

I have to say I’m really heartened by the efforts of some critics and arts journalists out there who are taking it upon themselves to spend time in the rehearsal room before they see a show. Those journalists who ask actors what they think of their role rather than where they like to have brunch on a Sunday. I encourage more of that extra-curricular exploration of our craft. We’re all in this together.

Critics, act well your part, for there honour lies.

Crew. Often hard to spot in the house as they only come out at night. You are the black-clad angels that make everything run smoothly. I know you work for almost nothing, often till the wee hours of the morning, with little accolade and often in highly stressful scenarios. Administrative staff, this goes for you too, and your important role in the house. The mental health figures from Victoria University’s Australian Entertainment Industry survey had some disturbing findings on the mental health of our roadies and behind-the-scenes workers. Act well your part, and ask for help if you need it, even if it’s not in your nature as the wonderful fixers that you are. We have your back. There honour lies.

Philanthropists. You, too, are a part of the theatrical house. A most welcome visitor. Come over any time. You rise above the panic and swoop in like superheroes. I’m constantly stunned by the amazing donors and supporters of the Australian arts. Willing participants who not only give their time and resources to the ongoing cultural conversation, but trust the artists and companies vehemently and vocally. I encourage you to encourage the companies you support to use your support to support other companies. Thank you for acting well your part. You bring great relief to the wellbeing of our industry, right when we need it most. We’re happy to set up a bed for you in the arts house.

Audiences. You are the most important part of the house. You are sitting on every piece of furniture, expectantly. Wide-eyed. Engaged. Cross-legged by the fire. We love you because you have shown up. You have chosen to take part in the world’s oldest ritual. Storytelling. You lend us your ears and your brains and your hearts. You are as present in your seat as you would be on the stage. We hear your every gasp. We thrive on your laughter. We see your tears. Without you, the arts doesn’t exist. Please keep coming. Please know that despite the rug being pulled out from under us, we will prevail with your help. The stories will continue. We will maintain the wonderful multi-voiced, multi-cultural dialogue that is Australian arts.

Audiences. Act well your part, for there honour lies.

There is so much more I could say about this big house we’re in and the tenants within. I have a wish list of things that I want for this house, despite all funding woes. I want theatre companies to employ creches so that theatre workers can return happily to their craft after having children. If theatre companies can pay for an international star, they can damn well pay for a babysitter. I want arts ministers to show up at productions where there isn’t a photo opportunity – come and meet the incredible workers on the ground and middle floors of the house.

I want every theatre company to employ full-time indigenous and cultural advisors. It’s not enough to simply tell culturally diverse stories. Those stories are often heartbreaking and can trigger certain emotional and psychological responses. Support needs to be there offstage as well, within the company and its administration. I want our acting schools and theatre companies to have mental health lessons and facilities available for all students and employers. Artists have to go to some very, very hard places, physically and psychologically. The workload is immense, for very little monetary gain. We’re expected to pull ourselves apart and put ourselves back together night after night, show after show. The repercussions of this are complicated and dangerous. We have lost too many artists to mental health issues. Their beautiful stories just stopped. We must not allow this to happen. Not in our house.

I am a writer who likes a happy ending so I’m going to finish this Philip Parsons lecture where I started it. Love.

I love being an Australian artist. I love telling stories. I love hearing stories. I love that our stories do indeed contribute to our nation’s wealth, in more ways than one. I love having my values, my beliefs, my long-held thoughts, challenged, twisted, reinforced or blown apart completely. I love the people. Humble, driven, determined, outspoken, gracious. A family as diverse and inspiring as the one that regaled me with stories in that hospital ward so many years ago. I love the elders of this industry that took me under their wing and who I can still call on, at any time, for advice. I hope so much to be an arts elder one day. I love the young talent coming through, from all walks of life, challenging me to write better for them, making my vision more peripheral as a human being. I love the determination in our industry. The robust, ribald conversations. That when we let each other down, there is also the determination to right things. I love the stories. They do save lives. I love a fight, and I have my boxing gloves on.

I love my house. It may sit in a neighbourhood of uncertainty right now, but I know its foundations are stronger than any crisis.

And because of this love – of the tenants, of the stories within, of the legacy and the future of it – I will endeavour to act well my part, alongside the wondrous household rabble of allies, for there honour lies.

Chookas, all.

Thank you.