27 June, 1998, Lake Tyers, Victoria, Australia

The morning after we got the news, I went out to your woodheap. There was that big old axe you used in the bush all those years ago, just as you'd left it, stuck in the chopping block like a signature. I split wood until the memories and the tears came flooding in. Then I dropped the axe back in the block, nose down, handle sticking up, as neat as you please. Just like you would, Dad.

Remember how we used to get around in the old Blitz army truck, the one you'd bought when you were 16 and drove for years before you got a licence? I hadn't started school, but I'd begun my education, sprawled on the petrol tank that doubled as a seat, my head on your lap, lulled by the old side-valve V-8 grumbling away behind its thin tin cowling.

I watched the way you used to pat the old girl into gear, those huge work-stained hands easing the gear stick through the unforgiving crash box while you double-clutched and caught the revs just right.

"Listen to her," you'd say as we labored up a hill with tons of timber or a bulldozer on the back, "slurping petrol fast as you could pour it out of a two-gallon bucket." And you'd laugh and sing King of the Road.

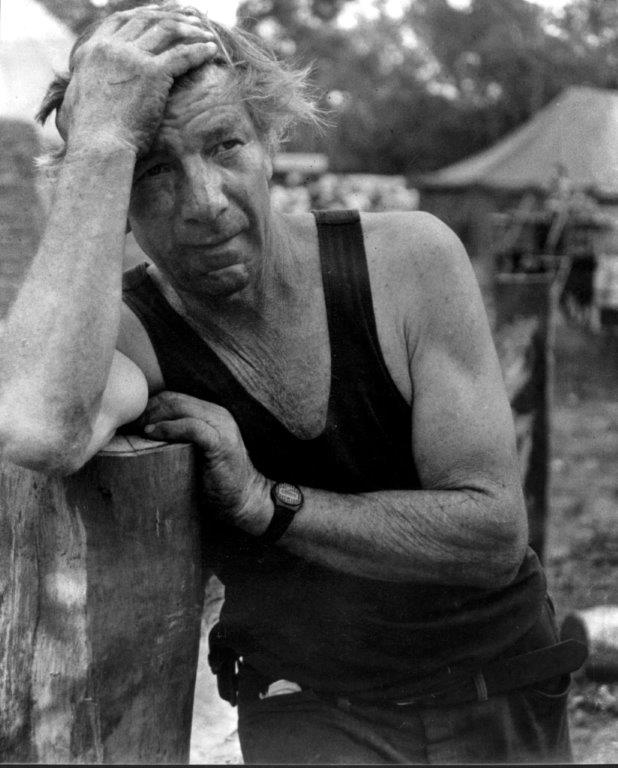

You turned 24 the week I was born, so I remember you as a young bloke, a father of three boys by 27. Fair-haired, under six foot and around 13 stone in the old scale, equal parts bone and muscle, common sense and good humor, wrapped inside a blue singlet with the honest smell of sweat and gum trees. You didn't alter much in 30 years. Later, people sometimes took us for brothers born a dozen years apart.

Like the best dogs, horses and people, you were tough, but never mean. We'd marvel at how you picked up hot coals when they fell from the fire, juggle them casually and toss them back. Your heart was a lot softer than your hands. Once, when a visitor produced sandwiches she'd made specially, you saw the one she offered had been fly-blown on the trip. Rather than hurt her feelings, you took it, thanked her, and ate it.

Chivalry, Mum called it.

Whatever it was about you, we liked it. Little boys in books wanted to be firemen or train drivers, but yours wanted to be sleeper cutters, like you . . .

You'd set up your landing in the shade, preferably to catch a lazy afternoon breeze sneaking up a gully from the lake. You'd fall a tree, measure off nine feet the ancient way, stepping out the log heel to toe, then saw it off and snig it to the landing with the tractor.

You'd belt the bark with the back of the axe to loosen it, then slit it open and lever it off as easily as a slaughterman skins sheep. You'd save sheets of stringy bark and, if it rained, we'd lean them against a tree, shelter under it and drink sweet coffee from your steel Thermos.

You used most tools well, but the axe was your favorite. Your good axe had an oversized head, razor sharp, and a succession of hickory handles worn silky smooth with use.

You could do nearly anything with it, and did.

At lunchtime, you'd put the sandwiches on a fresh-sawn sleeper, which smelt so sharp and sweet and clean, and cut them from corner to corner with the axe, as neatly as if you'd used a kitchen knife. You used it to sharpen the stubby carpenter's pencil for marking the ends of the logs. You used it as delicately as a scalpel to notch the ends of the log - right on the pencil mark - ready for the string line.

And, when you finished with the axe, you'd casually drop it, nose first, into the boards and stick it in perfectly, every time, with the handle rising just right. As neat as you please.

You'd shake the battered tin of blue powder to coat the string, stick it in those tiny cuts at each end, pull it taut, pluck it up and twang it. Presto! A straight blue line on the wet, virgin sapwood. You started the swing-saw and backed it rhythmically down the log, the machine straddling it with skinny legs on tiny tyres, the howling circular blade's cruel shark teeth throwing up a plume of sawdust as graceful as a rooster's tail . . .

And that's when your little boys got a chance to sneak into the bush, dragging the axe. We'd cut a whippy wattle stick, and "borrow" a length of your good cord as a bowstring. But only if you'd notch the ends of the bow with the axe. You always did, and more besides.

Sometimes, with two sure hits and a quick trim, you'd make a cricket bat from a sleeper offcut. You made us a ripper billy cart, the chassis made of hardwood, the front tapered with the axe, the steering a piece of light rope, like reins.

Your own childhood had been spent fishing, riding, shooting and swimming, and you always had a soft spot for childish pastimes. But you had limits. One day we squabbled too much over the swing you'd made with a tyre and a rope, slung from a big roundleaf tree. You vaulted the fence, axe in hand, and cut the rope without a word. Solomon in a singlet.

Later, after we'd reflected on our sins, you put the swing up again. That was you, Dad: slow to anger, quick to forgive and forget, always practical. You were never keen on punishment or revenge, and mostly turned the other cheek. About all that made you angry was injustice to another person or cruelty to animals.

You despised callousness or misplaced sentimentality that let animals suffer. If they were sick or injured, and couldn't be helped, you put them out of their misery.

With a bullet - or a lightning strike with the axe. "Quick and clean," you used to say. You always gave an old dog or an old horse a good feed and a pat before they took the walk from which only you returned.

Not that you liked killing anything. Remember your youngest boy conning you to let a sheep go instead of slaughtering it? You decided we could go without fresh meat rather than upset him. One of the few times I saw you angry in public was when you fronted a youth being rough with sheep in the saleyards. He got the message.

Our world was small, and it seemed to us you could do nearly anything in it that was worth doing. You could swim strongly, box a bit, shoot well and drive anything, and you taught us how. You'd started work at 14, got the truck at 16, had a bulldozer not long after you got the vote, and a pilot's licence. And, later, a couple of boats that gave us golden memories of summers on Lake Tyers.

You knew a thousand practical things, wisdom won from experience as a farmer and bushman.

Like the shine on your axe handle, it came only with time and hard work, but you were always willing to share it. All our lives you've shown people how to do things in that easygoing way, and kept learning yourself. "You can learn one thing from anybody," you always said.

You could sharpen any saw. You were a bush carpenter and mechanic, a handy welder and blacksmith. You grew up around horses, and helped drove cattle as a boy. You could stitch harness, use a stockwhip and a branding iron. You milked 26 Jersey cows and raised pigs. You could tan a kangaroo hide, set a wild dog trap, whistle a fox, rob a beehive, butcher a sheep or shear one. You could mend a chair or chair a meeting.

You cleared land, burning windrows and stumps, and sowed down pasture, but never wasted a stick of useful timber. You could quote Paterson and Gordon by the verse and drop a line of Shakespeare, Steele Rudd, Runyon or the Bible to suit most occasions. You could play tunes on a gumleaf, sing a lullaby in the local Aboriginal dialect, or make a bark humpy - a legacy of growing up on Lake Tyers Aboriginal station, where you were the only white player in the football teams of the early 1950s.

You played on heart and toughness. You had to. You played hurt every week because of what you nonchalantly called your "crook foot", a twisted instep caused by childhood polio that left you with a lifetime limp.

But your foot didn't stop you rucking four quarters without a rest in Nowa Nowa's winning grand final team of 1956. Your mates chaired you off the field, and they gave you a trophy for the most determined player. Mum still laughs about how all the local girls lined up to kiss you after that legendary game.

FOR A man who cut down plenty of trees, you loved them. You knew individual trees among thousands, and could find them in the bush years afterwards. You could look at a piece of sawn timber and say if it was grey or roundleaf box, mahogany or messmate, silvertop or stringybark.

Once, you amazed a neighbor by glancing at his new stockyards and telling him exactly where he'd poached the red box timber from, deep in the state forest two kilometres away.

When you went wheat farming on the open plains near Bendigo in the 1970s, you missed the tall timber and the whisper of wind in the gum leaves at night.

Perhaps that's one reason you were among the first to regrow trees on country where a century of ringbarking and burning had made bleak, bare paddocks. You planted, fenced in and watered hundreds of trees in a belt running a mile across the farm. You planted roadsides, and made plantations in places where salt was rising to blight the soil.

And still you missed the bush.

Your sleeper quota was gone, but you were younger than most sleeper cutters you'd known, and still strong. You'd been one of the last in East Gippsland to start out with a crosscut saw, a broadaxe and splitting wedges, tools that hadn't changed much since medieval times.

You learnt from axemen who'd worked in the bush since the turn of the century, and you spent your teens splitting logs into billets, then squaring them into sleepers with the broadaxe. And you never forgot how, even after chainsaws and swingsaws took over. Which is why, when Victoria's oldest farm, Emu Bottom, at Sunbury, needed authentic mortised posts and split rails to restore it so a television series could be filmed there, you took the contract. The owner, who was to become a friend over the following 20 years, was resigned to buying rare old fences to rebuild, but you told him you could split new posts and rails the traditional way. He was delighted.

And so began your second life as a bushman. You mortised posts and split rails for Emu Bottom, then hewed bush timber with the broadaxe to restore and extend its historic woolshed. People heard of your work and sought you out. You were invited to field days and demonstrations and started building showpiece fences and entrances all over Victoria.

One of your fences is part of a world-class jumping course at Werribee Park equestrian centre. You and an old mate put on an exhibition with the crosscut saw and broadaxe at the Scienceworks museum in Melbourne. You supplied and helped build more than a kilometre of picture-perfect post and rail on a $2 million vineyard and stud in the Yarra Valley.

Along the way you befriended a younger generation of timber men in the mountain ash forests above Healesville, loggers who'd grown up with machinery, but liked the way you could use old hand tools to turn timber into something special.

Like your own little boys long ago, they watched you study each log and niggle it with your hook to set it up just right before you struck a blow. They began saving logs for you that would split easily, helped you load up, shared a beer and a yarn with you after work and became your friends.

You were touched when one of "the young fellas" borrowed your wedges and a little advice to learn how to split rails and shape the ends with an axe. You obliged when a group dedicated to preserving old crafts asked you to give a step-by-step demonstration, which they filmed for posterity. And so, thanks to you, a dying craft has been saved.

But not the craftsman.

It took a while, Dad, but you've finally run up against something you can't fix with the axe. It's cancer, though none of us knew that until it was too late.

As I write this you lie in bed in the next room. I strain to hear you cough and clear your throat, and listen for the murmur of your voice, as you serve out the little time left to us. Those familiar sounds have become precious in a few short weeks.

If courage is grace under pressure, you've got it. As ever, your concerns have been for others, even as that strong body has wasted away, leaving little but strength of character.

I saw you sob for the first time in 40 years when you had to tell your mother you would die before she does. You thanked her for giving you a lovely childhood, and told us later you'd planned a eulogy for her that recalled those happy times. Instead, I'm writing yours, and it's the hardest job I've ever done.

You're sad, too, because you think you've let your grandchildren down. You'd decided to retire from farming and cut back the timber work to spend time with them. Only a few weeks before you became ill, you bought a nine-seat station wagon to drive them around. Instead, we used it just a month ago to take you on a last trip to the bush at Lake Tyers.

Well, Dad, you haven't let anybody down, ever. That's one reason so many people have come from all over to see you, as the news has spread on the bush telegraph. Every day, they stream in off the highway and down the gravel road to the old brick house to say goodbye. We knew you knew a lot of people; we didn't realise how many of them loved you, too.

You've always said that material things don't matter - that people do. "Remember, good friends are like gold," you told me the other day, your voice as strong as your body is frail.

Now, as the clock creeps towards midnight and the end of another precious day, so many memories still echo around my head, as they have these last bitter-sweet weeks.

You always liked the yarn about the stonemasons who were asked what they were doing.

"Cutting stone," one says sourly. "Making a living," says the next, matter of factly.

"I'm building a cathedral!" exclaims the third.

You've always been a cathedral builder. Always believed in what you were doing. Always shown that there can be art and dignity in simple things, in fashioning the functional so it pleases the eye.

Once, when you were burning huge windrows of fallen timber, watching a cascade of sparks shoot up to join the stars, you said that's the way you wanted to go. "I don't want to be buried in the cold, old ground," you said. "A man ought to make his own coffin and be put in a windrow."

Well, Dad, you've left your run a bit late to make your own coffin, but we'll do it for you. One of your friends has offered ironbark and box timber you dressed with a broadaxe for him; another some redgum from an ancient giant you felled, reluctantly, on the Campaspe River flats.

There'll be hand-forged horseshoes for handles, just the way you'd do it, and sprays of gumleaves from trees you planted. Your broadaxe, the one you started with 50 years ago, will be fixed to the lid. We might even get a truck about your own vintage and twitch you down tight with your own chain and twitch "dog".

You'll be gone, but you'll never be dead while we're around. You have nine grandchildren, and when we tell them how to do things, it will really be you that's teaching them.

When they learn to drive, they'll pat their way through the gears gently, like you did. With "just a trickle of throttle," like you always said.

When they cut wood they'll be using one of your axes. We'll show them how you split the tough ones. When they jam the blade, we'll show them how to free it without breaking the handle, the way you showed us.

And when they finish chopping, they'll drop it into the edge of the block, handle up, neat as you please. Just like you.

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone,

Kindness in another's trouble,

Courage in your own.

-- Adam Lindsay Gordon

Andrew Rule was the guest on the 44th episode of the Speakola podcast and recorded the eulogy for me.