12 March 2019, Flemington, Melbourne,Australia

Above clip is whole service. Andrew Rule’s eulogy begins at 43.40.

Dear Les,

Won’t keep you, mate.

A lot of people here have heard you say that.

“Won’t keep you.”

An hour later, there you’d be, still yarning.

‘Won’t keep you, Les’

It’s the password to the Carlyon Club. It had a lot of members.

For a quiet man, you could talk on anything: history; newspapers; literature. And racing, of course. Not just gallopers but trotters and horses in general ... and working dogs and drenching sheep and tips on practical harness maintenance.

When Truman Capote died the best obituary on him wasn’t in The New York Times: it was yours. He was in your head with Larry McMurtry and Hemingway and Lawson and Tolstoy … and other great artists like Harry White and Roy Higgins and Ted Whitten and Manikato.

All equal opportunity subjects in Les World.

In 1980 I was a kid on The Age. Neil Mitchell was sports editor and heard me talking about horse breaking. Might as well have been talking Swahili for all Mitch knew -- but he knew “Les” would be interested. Everyone at The Age talked about you, even though you hadn’t been there for a few years by then.

So Mitch calls you, has the big chat, then gives me the handpiece. And that was that. The start of a 40-year conversation.

Remember how you read the manuscript of my first book in 1988? I took it to the house in Sevenoaks St. It wasn’t hard to spot:

The only house in Balwyn with a tractor in the carport.

(Won’t keep you, Les.)

It’s the hour before dawn as I write this.

Best hour of the day, you always said: “Never miss a sunrise, Andy. If you don’t stay up all night get up before dawn.”

God knows when you actually slept.

Dawn spoke to you. I reckon you sensed racing stables coming alive while the ordinary world slept. You called it Racing’s Closed Society. You loved it and no one described it better …

The thump of the bags of dirty straw and the tap of the farrier’s hammer. Strappers swearing at horses. The blue heeler straining at the chain, trying to eat the new apprentice kid.

You understood them, the horse people who shared your taste for the Jockey’s Breakfast -- a smoke and a good look round. There are plenty of them here today, Les.

There’s Patto over there: Led in forty-six Cup winners and broke in a couple of thousand horses. I asked him once why they rated you and he growled, ‘Because Les gets it right.’

Apart from everything else, you’re the poet laureate of the track.

You didn’t invent Bart Cummings -- he did that himself -- but you were first to catch his likeness, way back in 1974. The eyebrows curling up ‘like a creeper’ are now part of the language. Then there’s the story about Bart and the Pommy health inspector who told him the stable had “too many flies” -- and Bart straightaway asks ‘How many am I allowed to have?”

You made Bart a national figure, bigger than racing. Without you, Les, there’d be no bronze statue of him downstairs.

(Won’t keep you, Les.)

The way that restless mind of yours hummed after midnight. It wasn’t just the stables calling, was it? Your body clock was set in the last Golden Era of newspapers, the 1960s and 1970s. You’d come home still wired from the daily miracle of producing a paper, stay that way until dawn, I suspect. Even after you left that life, it never really left you, did it?

You once said you wondered how you would have gone in America, testing yourself among the best in the land that produced so many of our heroes: Twain and Mencken, Joe Palmer and Joe Liebling, Runyon and Red Smith. You didn’t go, but their words came to you. You absorbed them. We all learn by imitation and repetition but you added other things -- intelligence, that prodigious memory -- and imagination

Under the homespun, hard-bitten exterior you were the most sensitive of men, with an intellect to match that soaring imagination. You showed it again and again, but never more than in the opening chapters of Gallipoli. It was mesmerising. The night I started reading it, I couldn’t stop. And I dreamed about the charge at the Nek.

The year Gallipoli came out, we got a plumber to our place. Seventeen stone of tattoos in a blue singlet. A van full of tools -- and sitting on the dash, next to a meat pie and an empty stubby, was a copy of Gallipoli. Norm the plumber just had to have it to read at lunch time. When I told you, you were delighted -- but not surprised. Your readers were real people, everyday people, you said. “You’ll never sell many books if your readers are only the people who read broadsheet reviews,” you told me.

(Won’t keep you, Les.)

Some of us got to see you lay out a page, write a killer headline and caption and rewrite copy, turning lead into gold. You could do nearly anything in a newspaper except run the presses. The truth is, you were always one thing: a perfectionist about anything that interested you.

I once went up to your study/ library. It was also a smokehouse, you had maybe 1000 books in there and every one was pickled in tobacco smoke. You reached into your storeroom, (where you kept a perfect WW1 officer’s military saddle, as you do) and grabbed a bridle you’d made, stitched to fit just one horse. No buckles. Made to fit like a glove. Perfect.

That was you, Les. You made things perfect. But words were always top of the list.

I saw you get one letter out of place in 40 years. I make more mistakes every day.

As Chopper Read said, ‘Even Beethoven had his critics.’

But you don’t have many. You collected friends and admirers the way a lamp attracts moths.

As Neil says, some of your ‘boys’ were girls -- like Jen Byrne and Corrie Perkin and Virginia Trioli and Jill Baker.

Last week when the sad news broke, a group of your female admirers gathered for a drink and swapped Les stories. One leaned over to Jen Byrne and said, ‘Les wrote like an angel -- but there was always one horse too many’.

Don’t worry, mate. That one’s from Sydney and she wouldn’t know. AS IF you could ever have one horse too many.

Les, you’re a father, grandfather, prose stylist, critic, historian, mentor and mate.

A teacher who never stopped learning.

You turned knowledge into wisdom. Best of all, you were kind as well as clever. A rare quinella in the biggest race of all, the human race.

Pushing words around the page, you said writing was.

You pushed millions of words for nearly 60 years. Every one ground down to a perfect finish. It was the only thing that really mattered, apart from your family.

But you knew that what mattered more than the words left on the page were the ones you left out. Your tribute to Denise in your last book says it all: “I owe her more than words can say.” There it is: a lifetime of love and gratitude in eight words.

Les, we’re all we’re all going to miss you more than words can say.

**************

Andrew Rule also wrote a newspaper obituary for his great friend which appeared in the Herald Sun and is reproduced with permission below.

Les Carlyon, giant of Australian journalism, liked to quote Red Smith, giant of American sports journalism.

“Dying is no big deal,” Smith once told mourners at a friend’s funeral. “The least of us will manage that. Living is the trick.”

Carlyon fetched that line from his prodigious memory in honour of his contemporary Peter McFarline, sports writer and once Washington correspondent for this company.

But the sentiment — about living with purpose, rather than making a grand exit — fits Carlyon himself.

Right up to the final weeks of the illness that ended his life this week Les worked at the craft that made his name. His soaring intellect was anchored by homespun principles.

He was always on the reader’s side. He never joined the authors “club” nor any other, really, except the Australian War Memorial board he was invited to join because of his remarkable military histories, Gallipoli and The Great War. He was welcome at any club in the land, especially of the horse racing variety, but would usually be writing or with his wife Denise and their children and grandchildren.

Les had his weaknesses — cigarettes and black coffee, reading and racing — but never succumbed to the temptation to take himself seriously. But he did take his work seriously. It showed, in sentence after flawless sentence of crisp prose he kept up for nearly 60 years and millions of words.

Les Carlyon was born in that increasingly foreign country – 1940s rural Victoria – and never forgot it. Part of him was always the kid from up Elmore way but some talents need a broader canvas. Like his fellow artist, the late champion jockey Roy Higgins, young Carlyon quit the country to further his career: in his case to work at this newspaper’s forerunner, The Sun News-Pictorial, in 1960.

The Sun was as unpretentious as it was popular. It relied on appealing to ordinary readers. Carlyon the cub reporter quickly learned to make words short and sharp.

By age 21, fitting part-time study around full-time work, the rising star had been lured “across town” to write for the opposition newspaper, where he would cap a rapid rise to become editor at 33 before suffering a bout of the recurring pneumonia that has finally ended his life. He would later return as editor-in-chief at the Herald & Weekly Times but was best known for his precision at the solitary business of writing.

“Hero” and “champion” are so overused as to debase the currency. Carlyon was one of few entitled to be described that way by the many who admired him.

To want to meet a writer because you like their work, a writer once noted, is like wanting to meet the goose because you like pate. It can be a disappointment to meet heroes, but meeting Les was no let down. For a modest man, he was a good talker about shearers or Shakespeare and from Tony Soprano to Tolstoy.

He wasn’t one for pomp and privilege, had a faintly puritanical distrust of the trappings of wealth and power unless maybe it involved an unraced two-year-old. Yet he was on first-name terms with the wealthy and powerful.

When Les was “gonged” with the top award in the Honours list in 2014, it was a great thing and not befoe time. But Leslie Allen Carlyon AC was still “Les” to his friends.

He delighted in the story of the English publishers who decided (wisely) to publish his best-selling Gallipoli, but rejected his lifetime byline by printing “L.A. Carlyon” on the cover.

It seemed to the Londoners no serious author’s name could possibly be contracted to “Les” on a hardback in England. That made Les laugh. All that mattered to him is that readers liked the book.

For him, getting the story right was everything. He did it for decades and helped others do the same.

He was not only talented and tenacious but patient and kind with it. Who knows how many people he called — and how many called him — for “a yarn” late at night.

He shared knowledge without lecturing or hectoring, ego or spite. Few touched by genius are as generous. He treated his extended family of writers, reporters, publishers and broadcasters almost as well as he did his favourites — horses and horse people.

Jennifer Byrne would become a national media identity – in print then television – but nursed lessons learned as a teenage reporter from her first news editor.

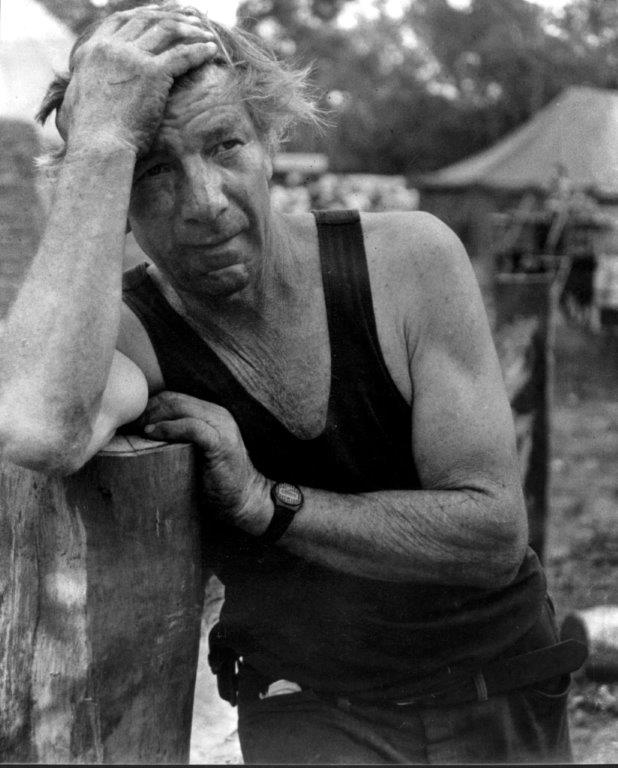

Byrne recalls a “lean stripe of a man built like one of the racehorses he loved who took a bunch of know-nothing cadets and showed us how to become journalists.

“He showed by doing, by being the best writer on the paper. He wrote like an angel and produced stories which were also lessons. He was scrupulous about facts, generous in spirit, his stories full of unlikely winners and gallant losers; you could call them Runyonesque except for their depth and elegance.

“As time passed, we became friends, and I saw how much work went into what read so easily. He gave us chances we muffed, and helped us do better. He praised lightly but when it came, it was like a sunburst. To Sir with Love? Well, yes, but I am eternally grateful for the advice he gave and example he set, as are so many others. Les was the best of our business, and unforgettable.”

That testimonial speaks for the many people Les helped. They know who they are; they could staff their own newspaper, radio station or publishing house.

Carlyon influenced his followers deftly, the way the best teachers can. As for his own influences, there were the Americans like Red Smith and Twain and Runyon and Joe Palmer, but there was also Henry Lawson and Tolstoy and more.

He wrote about any subject with flair – but about racing with something like love. His collection of racing stories, True Grit, has barely been out of print in 25 years. No one does it better.

He went to Tasmania after the Port Arthur massacre and wrote what he saw at the scene. He wrote a timeless account of Princess Diana’s funeral. He went to Hiroshima to record the 50thanniversary of the atom bomb. He wrote about heroes from Bradman to Ali to Clive James and about those grand stayers Kingston Town, Tommy Smith and especially Bart Cummings. He wrote about business and politics, sport and war. He never wrote about himself.

Carlyon grew up in the shadows of the Depression and war, before the fashion for self-promotion took hold. He wrote countless words across decades but the “perpendicular pronoun” is as rare in his work as a spelling mistake or a clumsy phrase.

Carlyon did not invent Bart Cummings but was first to capture the likeness that helped turn a horse trainer into a national treasure.

He wrote of Cummings: “He was pragmatic and mystical, likeable and unknowable. Racing might be about desperates. Cummings was too casual to be desperate. He wasn’t like anyone else: he was simply Bart.”

The theme is that by being his own man, ignoring fame and fashion, Cummings accidentally found both, to become a figure comparable only with Bradman – in stand-alone success and bulletproof self-belief.

Les Carlyon spoke all over the world in the last 25 years but never more movingly than at the memorial service for Roy Higgins in 2014.

Everyone liked Roy, he said, “because he was so easy to like. He was the benign presence, he was humble, he was generous, he was courteous, he didn’t carry grudges, he didn’t look back, he wasn’t sour or cynical. He had time for everyone, be they the prime minister or a down-at-heel punter cadging for a tip.

“He was a great human being and that might be the biggest story, because it’s harder to be a great human being.”

All words that fit the man who wrote them.