30 October 2017, Melbourne, Australia

About three days before Johnny died, as his physical strength was waning, he signalled with his hands that he wanted to talk to me alone. Everyone left the room and we closed the door to his study. I sat on the leather chair on his side, his body perforated with contraptions called butterflies, from which drivers and needles could easily be injected to ease the unbearable pain caused by the cancer that was rapidly burrowing through his bones. What did he want to say? He just looked at me, his eyes already hollow but strangely sparkling with that look I’d come to recognise over the past ten months—a mixture of bewilderment, of bemusement, of bereavement, the latter less for his oncoming fate than for his family and especially for my parents.

He shrugged his shoulders. ‘Do we have anything to talk about?’

Umm, I thought to myself. How do you answer that question?

‘Talk to me,’ he urged. ‘What do you think?’ His voice was croaky from the primary cancer in his lower oesophagus which miraculously never affected his appetite; if anything, it enlarged it, and summonsed meals from Ilona Staller to his hospital bed be it in Cabrini, Prahran hospice or his study.

In that one second before I answered him, I looked at him lying there, and then at the framed picture behind the bed of Johnny standing with our great-Uncle Wiociou, an old behatted man, younger in the photo than our Dad, who brought Mum out to Australia after the war, and our lives flashed past me in that proverbial way. Just as his bodywas being eaten particle by particle, so too did I see our lives cell by cell, not the grand legacy of his brilliance and larger-than-life character, but the minutiae, the myriad memories of a life shared and lived, as TS Elliot says, measured by coffee spoons, until the last sip more than the last supper.

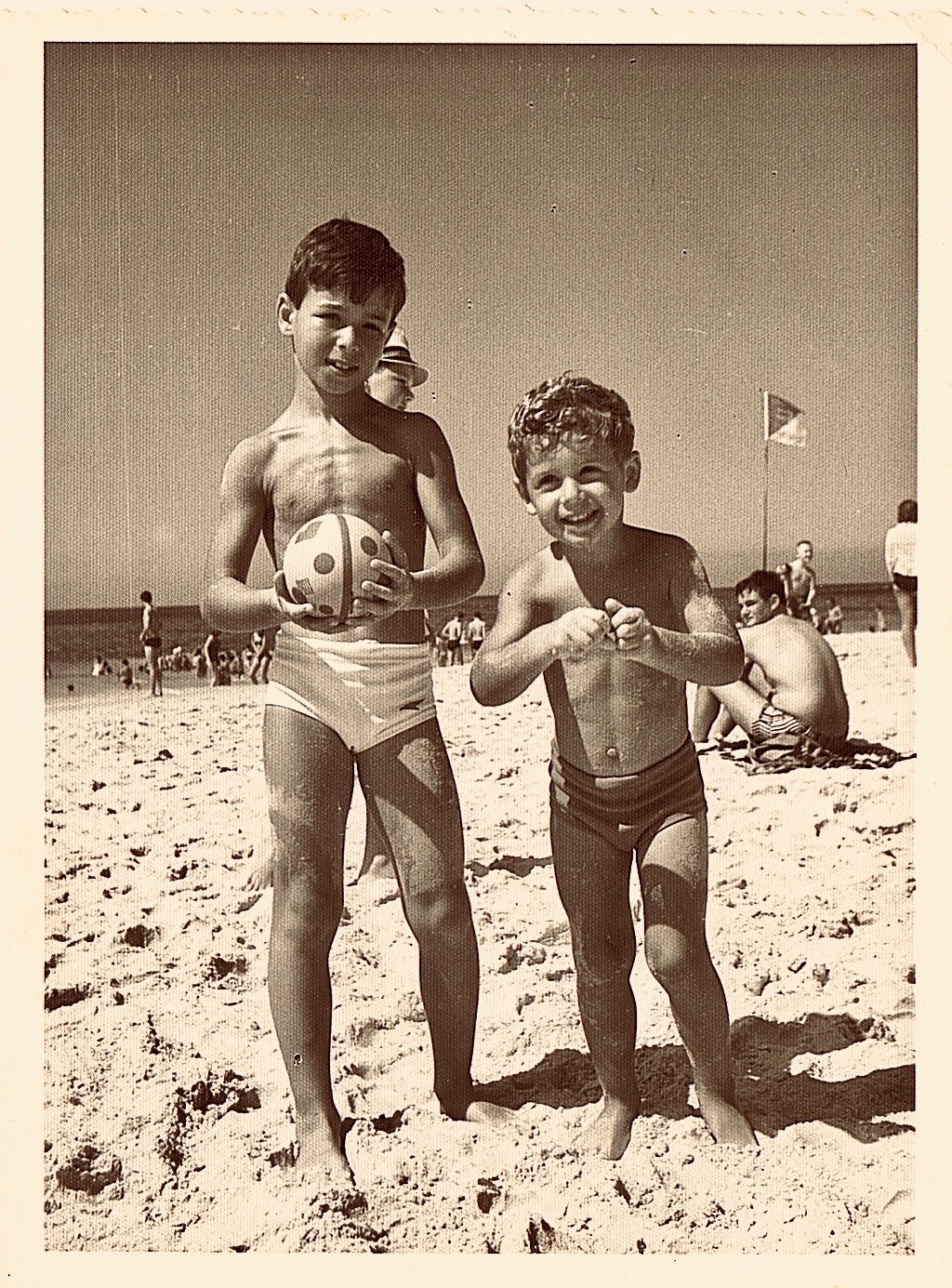

And I realised that above all, what shaped us as brothers over the 62 years of his life, was that for me the filmic reel of our lives, unedited and continuous, began five years before I was born. One of Johnny’s most annoying habits was that he loved to test waiters about this fact and ask who was older. Wasn’t it obvious, that I, who inexplicably retained my hair, was the younger one? Yet sometimes he got the answer that he wanted, or that might have actually appeared to be true because he had such a young smooth face like Yossl’s. If I was to write a book, and I can assure you I won’t, I’d call it not Thirty Days but Five Years, because it was the theme that governed and shaped our relationship and differences.

My Dad came to Australia in '48, my mother in '51. Maybe Johnny had a better knack for languages as he did for music, but it partly explains why Johnny was able to hold a fluent Yiddish conversation because by the time I was born my Dad learned to speak a poyfect English from interacting with all the migrants in his factory in Brunswick. When Johnny and Iwere videoed chatting a few days before that last conversation, I was trying to dig for my earliest memories. But that was the wrong question. His were the earliest memories, something so obvious I’d never realised it. He told me that he remembers when I was nine months old and was rushed to the hospital for an emergency tracheotomy. He recalled the panic in the house as I lay in hospital in an oxygen tent for weeks. He would have been six years old at the time so of course he remembers but I never thought about that. My mother likes to say that was the start of her depression, not the Holocaust, not losing her mother straight after the war, but almost losing her secondson. Now that’s a heavy load to carry, but talking to Johnny I think he carried the load more.

We both recall going to Hayman Island with friends who are here in this room (Joe says it was in 66; Les says, a few days after August 27, 1967. Johnny for sure would have known the exact date), but of our parents only Dad came, he in his larrikin spirit, dressed in one photograph as Carmen Miranda and parading with a bottle of champagne like Maura from Transparent. Where was Mum? I didn’t know. But I think Johnny who was already eleven did, and he always knew after and experienced more than me the effects that apparently the near loss of a son brought into the household.

It’s usually the first son who is the spoiled one but perhaps that early incident set the tone for our relationship. My parents don’t hesitate to repeat the story of how I would walk into Franks toy shop, then located next to Las Chicas, and say, ‘now what haven’t I got?’ Johnny wasn’t spoiled in the same way. When I cried Mum would say, ‘Give in to your brother Johnny,’ to which I would learn the refrain from an early age, ‘Johnny give in to me. Let me have it.’

So, it comes as no surprise that over the past month, moving home, I was searching cupboards, and amongst the treasures I discovered were records with Johnny’s name on the cover, and books inscribed with Johnny’s signature. And amongst it all, I found this one object, something I opened and believed was mine. A collection of 78 records in brown paper album sleeves, with songs that I remember. I remember singing them with Johnny while he was in the bath, and I—this might be my earliest memory—would dance to, still dripping water on the tiles. Peter Ponsil and his Tonsil – those words ring in my ears but not the tune, but I certainly remember my favourite, How much is that Doggy in the window/The one with the waggly tail, to which we would both bark, Woof woof. Yet two nights ago when I retrieved the maroon album, I was shocked to open it and discover that my mother had written in her florid hand-script that never changed: ‘For my—The my crossed out and replaced by our—darling Johnny. From Mummy and Daddy.’Across the top was the address, 22 Malvern Grove, to which was added Melbourne, Australia in case someone might find it and think to return it to Poland, meaning Johnny was given this precious gift when he was four or five, before I was born.

Now I wish I could give you back those records Johnny and woof together like little children, but I can’t. I want to keep them for myself but they belong to your family, so that they can play the songs to Rudy and Addy, and to the grandchildren I know you wanted more than anything else to live to see.

Most of our earliest memories revolve around music. I drove you crazy with that record player I kept on the desk in Edinburgh Avenue behind my bed. It was shaped like a brief case with a clip, a mottled grey colour, on which I would continuously play Mary Poppins. Where did that record player go? And we both remembered going to Ciociou and Wiociu’s house in Elwood, our surrogate grandparents, which smelled of gefilte fish, Ciocius arms wobbling like the gulleh—calves foot jelly—she made, and playing soccer with Max, who introduced us to Fiddler on the Roof in 1966 just before he went off to Israel and was killed in El Arish during the Six Day War.

Or perhaps an even earlier memory is of us on a holiday in Rye, where I had the mumps, looking out the window and seeing you playing with a soccer ball. I was always the sick one and you were always the healthy one, and could never tolerate illness. You were always one step ahead—five years ahead—it was because of you when I came to Scopus Mum moved me to Mrs Traegar’s class because you were the star student, and so if I followed in your footsteps, some of it would rub off.

But I wasn’t the only pampered one. You told me last week how Dzadzi would have to roll his car out of the driveway when he left for work early, so as not to wake you up, a feat that almost matches me warming my school socks against the blow heater. We were spoiled by a doting mother who will always remind us how she lay on the floor while we studied for exams—in primary school, not to mention HSC, despite receiving her schooling in a DP camp in Germany. We can’t forget the constant holidays to Lakes Entrance and Surfers where we stayed at Island in the Sun and then the Chevron, Mr Kisch’s apartment and Surfside Six where the Nebyls stayed and formed a bond with our family before we became family.

And then there was the time soon after the Six Day War you vanished with Mum and Dad to Israel, and I was left with Aunti Dzunka and Uncle Boruch without prior warning. You stayed with Charlie, or Yechiel as he later became, at the Hilton hotel, yours and Anita’s happy place. But on that early stay in that iconic concrete block when you were barely barmitzvahed, Mum and Dad chuffed off to Europe, and you were left alone in a hotel room with Charlie, from where the two of you booked day tours on Dan buses.

No wonder we always had a string of live-ins—Rula, Lucy, and Katarina, and in later years, Que- Jenny, to spoil us.

There was only one time you were sick, Johnny, but that story has been passed down as one of heroic stamina, not unlike what we witnessed these past months. It was on your barmitzvah day. It goes without saying you had the longest parsha, not just a long one but a double one, Vayakhel-Pekudei, which satisfied Mum, whereas mine was so short that she asked Mr Caspi to change it to Bereishit, perhaps establishing that playful rivalry between us in those subtle maternalgestures. You were so sick with the flu, you almost didn’t make it, but like a true warrior you walked the distance from Caulfield to Elwood, stood on the bimah, and recited the whole shebang perfectly. Auspiciously, when we opened Shira Hadasha, it was your barmitvah recitation that launched it, and only you had the capacity to bring to a shul that was spurned by Mizrachi and had a brick thrown through it, the likes of Mark Leibler. I never asked who wrote yourbarmi speech – probably you – but when it came to mine, your September holiday in Surfers was spent under duress from Mum to write my speech, who also enlisted Joe Gersh to the task. By then, you were a teenager, long haired, while mine was ungainly and curly. As Mum will attest, you had girls galore. I won’t name them. I still remember as a little boy being shocked when Mum stormed into your room and like a sniffer at the airport, screamed, I smell druks. I smell druks. And you pleaded it was just scented candles. I never asked you, which was it? The pool was always awash with your friends, but in the end, as from the start, it was Anita who captured your teenage heart.

And then in my first form, everything changed. You went to Israel for a year, and got caught up in the ‘73 war, and I don’t mean the war with Mum about dropping out of medicine. I’ll never forget Dad’s terrorand how he wanted to fly to rescue you as if he was on an Entebbe mission. I still remember the screaming match at home when you returned from Israel and dropped out of medicine for a second time, and then— and this is the heart of it for me— you disappeared. You went to live in Israel and from that moment, I became an only child. My life took a different course. Those were the formative years of my teenager-hood, when I was spoiled and went on family holidays to Ekelpekel as the men innocently pronouncedAcapulco, but without you.

And one of the things I told you in your last days at your bedside, is that even though you weren’t there, and perhaps I resented it a little, you were my hero, my older brother of five years, who showed me what it is to live a life of purpose, who instilled in me my love of Israel, and who planted in me my left-wing Israeli politics. And so,when I went to Israel for my gap year and escaped Yeshiva, it was to your home, in Beit Hakerem, that I gravited, treated by Anita as a son, and by the Nebyl clan on Habanai and Hechalutz as family, and greeted each time by Boyce, who reminded us later of our Spoodles.My passion for Jewish education came from you, Johnny, my rejection of law was inspired out of a desire to return to Israel like you, and then when I got to Israel with Kerryn after Oxford, we played trading places, and I moved into your apartment in Beit Hakerem where Gabe was born.

How is it that as you lay dying, I found myself staring at your bookshelves, and recognising almost every book as one that I also possessed? How is it that we both shopped in the same places, and had the same taste for designer labels? We were so close, our homes diagonally across the road, that it felt as brothers we were in each other’s pockets after so many years apart. At times, it was tight in that fraternal pocket, and so we found ourselves arguing over the one percent that differentiated us, how to characterise the occupation, sparring over ideas but sharing the same worldview, and love of wine and food at our regular Knesset gatherings.

But Johnny, did you have to go so far and mirror what had happened in my life only one year earlier by getting cancer. No one could have arranged our tight enmeshment as brothersmorepoignantly than the fact that Kerryn was buried on your birthday, and that you died and were buried on hers. Such is the tragic circularity of life, the unscripted coherence that transcends the chaotic banality of our days, or what one friend called the bewildering mindfuckery of life. And so we bonded in a new way. Having delegated the tasks of caring for the pragmatic things in life to Kerryn and Johnny, I was dumped with a new kind of responsibility. Johnny was surrounded by a network of medical friends who all went to the greatest lengths to help and comfort him, but for some reason, he turned to me, alongside his family, to be with him at every appointment—from that first PET scan, back to the rooms of the same oncologist where I was tempted to imitate Jack Nicholson’s terrifying line from The Shining, Here’s Johnny.

Being a medical cancer expert, or rather an expert googler unafraid to read the scientific gobbledydook on Google Scholar, I knew that once again we were faced with an ordeal that would last approximately ten months. I knew your care was palliative, the most fateful charade, that would extend Johnny’s life to give him the chance to prepare himself and family for death. And Johnny, as we all know, did it his way, with fanfare, using his skills as a genealogical botanist who knew every branch of every family tree, exactly like our father, to invite everyone into his life using black humour around his dying, hobnobbing and literally hobbling on crutches with politicians in the Hilton lounge to your own lounge at Aroona, right until the last day, when we brought the songs of the Seder table into the room where your very own Von Trapp family sang your favourite songs in harmony. You even flirted with the medical staff, and when you were well, gave copies of my memoirs to the nurses, many of whom remembered me, and who read it with one eye on you, reduced to physical immobility but never once losing your remarkable mental agility. And the reason the nurses could afford to sit back is because, angelic wonders that they are, the hard work was being executed by the family. I admit, I was sceptical. How would they manage? But manage they did. And boy did Johnny know it, even as he issued instructions while on substances we wished we could steal from his kit. I will never forget the images of the kids sitting in the study as though they were characters in Breaking Bad, filling needles, tapping on syringes, and ultimately easing Johnny’s unbearable pain with the alchemy of methadone and devotion.

There is so much to grieve for, but none of you—Timnah, Nadav, Mayan, Gilad, Karni, together with your partners who adored Johnny, can ever feel guilt for a second that you weren’t there, by your father’s side giving him exactly what he wanted, until those final seconds when you wrapped him in his final resting garb.

And then there was Anita—Anita who began by repeatingthe mantra, I’m going to throw myself into his grave. How can I live without Johnny?We all worried for her, and we still do, but in a different way. Anita turned into Wonderwoman, as if she’d been supercharged by a dark sun, and literally ran from one end of the house to the other servicing Johnny’s needs, injecting him, gathering blankets, emptying catheters, maintaining his dignity in moments where only love could cover up the indignity caused by his immense pain. Johnny might have been the hero who never complained about his illness, even as some of us sat in the lounge room blocking our ears and flopping our heads on our laps to drown out the sound of his agonising yelping when being showered. But Anita, with the help of one of the kids, or a nurse, did it all, with so much strength that she replaced the refrain of despair into one of defiance and inspirational strength. Right down to those last days, when she became a foetal ball, curled over him in love, crying for Johnny as though they were back at school, as though time had dissolved and joined the beginning with the end.

And so, when Johnny asked me, do we have anything to talk about, I knew what to say. I told Johnny the simplest truth. That everything will be OK. Starting with him, that you Johnny will be OK, that while you’re being robbed of years, no, of decades, you’ve lived a good life, a wonderful life, and that once you’re gone, you won’t be asking questions anymore. And then I assured him that everyone else will be OK. Anita, because she’s shown him how strong she can be. I went through each of his kids, and said that every one of them will find happiness, exactly as he would want, and that I would always be there for them, as would their other aunties and uncles, Lani, Nay, Chezy, Sylvia, Gid and Shelley, and brood of closely-knit cousins as well as friends, including Caron and Ralph, Lorraine and Simmy, who were in the foreground and background from beginning to end.

Johnny was also worried about me, and asked how I was coping and so many times he told me how happy he was that I’d started a new life with Michelle, or Mooshes as Anita has always affectionately called her. He wanted to see photos of our new apartment in St Kilda opposite Luna Park. He asked it selflessly, and I think it brought him comfort that I had found my way back to life, and that my kids, Gabe, Sarah and Rachel, who adored him as their Uncle, and who Johnny showered with praise and love along with their partners, were managing to balance their irrevocable loss with a life of happiness.

But most of all, he was worried about our parents, Buba and Zaida, for whom he put on an academy award winning performance each time they entered the house, reserving his waning energy for zestful greetings to put them at ease. Johnny and I always joked that we had good genes and would live till an old age. We also internalised the legend that our parents taught us, how to dance in the darkness of sorrow, as they did at the annual Buchenwald Ball. But we were no longer so sure, how they could take another loss in their life, and endure such immeasurable tragedy. To be honest, I didn’t think they could do it, but now, in these past few days, seeing what I’ve seen, my one regret is that I didn’t say to Johnny that Mum and Dad will also be OK. Shattered forever, weeping tears and sharing broken Valium tablets, but all things considered, meaning you can’t turn shit into gold, they will be OK like the rest of us. We saw it in the way Mum, after screaming her own refrain, Take me, Take me, would sit in his study while her son was dying, 57 years after she almost lost me, and kiss his kepelehand then hold his fingers and call them piano fingers, such beautiful fingers he has, and kiss each one, those fingers that she had created. It’s time to leave the room, we would say, but like a baby she shook her head and said to one of the grandchildren, I’m as close to him as you, my dear, and then add: ‘If it wasn’t for me, you wouldn’t be here.’

And how could Dad survive, we all wondered, when he stumbled into the room, and each time knew to lean over Johnny, and whisper the right words into his ear. ‘Don’t worry. I’ll look after the children,’ weeping and then repeating the words again, ‘I’ll look after the children.’

At the funeral, despite or because of their hysteria, Mum once again found the strength to do what she had done for Kerryn. She stood up from her chair, and demanded a shovel, and cast spadefulsof earth over her son’s grave, saying ‘I should be the one in there.’ And then she turned to her Yossl, and gestured that it was his turn to face the bitter truth, for which they will always weep but also—I know it Johnny—stand and survive.

We know how much you loved life Johnny. Those words, Mi Haish, Who is the person, were written for you—hechafetz chayim – who yearns for life, ohev yamim, loved his days, right to the last. ‘If I could bottle this time, I would,’ he said, notwithstanding his suffering. And now we promise you—who began life as recorded on your birth certificate in 1955 as Gollini Bekiermaszyn, and over 62 years filled that bottle with memories as vast as the oceans, that all of us will be OK, and that in the celebrations to come that will span generations, od yishama, ‘once more will be heard’ the sound of gladness and joy.

Woof Woof.

We love you Johnny Baker.