16 March 2016, Shira Melbourne, Caulfield, Australia

The video of this hesped /eulogy may be viewed here. from 30 mins

When Kerryn gave her stupendously brave speech at Gabe’s engagement she practised it on me several times so that she could drain herself of the emotion. I’ve only had one chance of reading mine to her and I don’t think I’m ready to get through it - but I’ll do my best (and if I fall asleep or slur it’s because I’m on sedatives, which are on steady tap from my father). You’ll have to excuse me that I have my back to Kerryn but she has heard this eulogy a few days ago. I was given the stamp of approval through her smiles, though she did warn me that she was undeserving of my words and that it was too long. I haven’t changed any of the praise but I’ve cut the words in half, and it’s still too long. So bear with me but brevity feels like an injustice to our darling Kerryn:

Nine months ago on a Thursday night Kerryn and I were eating dinner at one of our favourite haunts, Ilona Staller. It was part of our privileged life, meeting an array of interesting overseas visitors. This time it was dinner with Sergio Della Pergola, the world’s foremost Jewish demographer whose job it is to count every Jew and project how many of us would exist in the future. I never bothered to ask how he accounted for the randomness of life - the calculus that can reduce his figures by a singular one - an infinite one - simply because life catches a person out with unexpected happenings. It was a fascinating dinner, full of laughter and lively conversation, and also my favourite pasta which is a permanent item on the cash register. Kerryn indulged herself with chips and later that night woke groaning to regret her choice of fatty food. Only in the morning did she admit to me she’d been kept up the night before by similar discomfort.

It was from such delights - a charmed life of exciting encounters, travels, dinners, augmented by anticipation of a summer of planned trips to Rwanda and Zanzibar - that prompted Kerryn to check in with a doctor. The doctors were quick to make the diagnosis and by Monday we got the ominous call as Kerryn was exiting what was to become our second home at Cabrini hospital. ‘Come immediately to our office,’ she was told, X-rays at hand. Pause. ‘And can you bring your husband Mark with you.’

We met outside the clinic and and walked through the doors in a numb state, aware that Kerryn’s self-diagnosis of gallstones was more malevolent than anything we could imagine. The doctor broke the news gently with the quizzical words, Linitis Plastica, quickly adding ‘And don’t ask any questions that you don’t want the answers to.’

That in itself was the answer we dreaded most and what followed was a string of phone calls and appointments which landed us in this surreal world that literally turned our lives upside down. The images of that week will always stay with us - poor Gabe, our older son, who believed that by sheer will and love he could fix things and to his credit, his outpouring of tears was almost enough to convince the doctors to alter their diagnosis. Rachel who was the only one living with us in Aroona at the time, in the midst of exams, lifting our spirits with her can-do anything hands - cooking, shopping, comforting. And Sarah, who walked in the house from work and expressed the the only words that could adequately sum up our feelings. Falling into Kerryn’s arms, our doctor intern cried, ‘What the fuck!’

Indeed, that word was used more than once, not as an obscenity, not as an accusation with an accusing or belligerent finger held up, for Kerryn never once let go of her equanimity or expressed anger, but something deeper, an acknowledgment of the bewildering mystery of life.

In one such moment when Kerryn was violently vomiting, she was leaning forward on a hospital bed, her back being gently stroked by a nurse who despite her experience on the oncology ward felt a surplus of empathy for Kerryn’s suffering. Soothing her patient lovingly, she whispered gently to Kerryn the only words she could offer in the face of the futility of medicinal healing. ‘We have to pray together,’ she said. ‘Do you pray?’ Kerryn mid-vomit played along. ‘Yes. Sometimes I pray.’ And in perfect poise that ruptured our image of Kerryn’s gentle manner, added: ‘And sometimes I just say Fuck.’

That’s right. Like Primo Levi in the camps who acknowledged that ordinary language like hunger and cold no long make sense to the suffering, Kerryn had to reach deep into a jarring vocabulary to articulate something that expressed our entry into a parallel planet of anguish and apocalyptic eruptions. For our idyllic world was spinning out of control at rapid pace. From that healthy meal on Carlisle Street - not just a meal - from a healthy and vibrant life of work as a family counsellor and doctor, of travel, as an engaged mother, sister, daughter in law, auntie, friend - Kerryn found herself gripped by a dybbuk that was taking over her body. Within days of the diagnosis, she could no longer lift her left leg. After one of a battery of tests on a Friday she insisted to the nurse that she would have to leave early because she had her regular Friday night blow dry at Hollywood Cutters. She made it on time, but as I watched her in the maze of mirrors, I saw her writhe in pain. Where was this monstrous alien coming from and what was it doing it to her?

The weeks ahead that culminated in her first chemotherapy, felt like a war, a metaphor that often accompanies cancer with its reference to patients as warriors and treatments as second and third line battle positions. That day, two weeks after the era that divided time into BC - Before Cancer - to AC - After Cancer - we brought Kerryn home. The family troops all did their bit. Ann came in with supermarket trolleys of fattening food, delivered lovingly to rescue Kerryn. The entrance to our home that greeted us was a shrine of flowers fit for Princess Diana. Baskets of food and kugelhoff were left at the door. We settled Kerryn on the couch to watch Masterchef and within an hour the toxic fluids erupted. Sarah with her medical training came to the rescue, washing towels and helping Kerryn through the throes of nausea. A flash of memory struck me that moment, one of many moments of history repeating itself. Kerryn had been an intern when her own mother was suffering cancer. She had injected her mother with morphine, a fateful act which impacted to some measure on Kerryn’s career choices. I vowed that I would never let Sarah be Kerryn’s doctor - only her daughter - but not before we let Sarah clean up the mess.

My job came at 3 am, the fulfilment of a craving for something totally unprecedented that could only be got from the supermarket. Teddy Bear Biscuits. The cravings recalled an earlier time, when Kerryn, pregnant with Gabe in Jerusalem, sent me on regular missions for blintzes, the best of which came from the terrace of the King David hotel. The mission accomplished yielded nothing more appetising than an ear Kerryn nibbled on, the rest of the teddy bear left forlornly on a plate while we rushed Kerryn to ER to cope with dehydration, nausea and the creeping tumour; well, not creeping - it was more like a rearguard blitz that took at least ten days to quash.

After the seventh day on the fourth floor of Cabrini hospital we were transferred to the remarkable Prahran palliative hospice - on the surface, a cosy B & B populated by angelic legions. ‘We’re not ready,’ I wanted to scream. That was when I had my first death nightmare, sleeping in a low pull out sofa alongside Kerryn. In my dream, I was driving in the dark to Norwood Rd, our first marital home. From behind the front door, near the piano that Kerryn had bought though no one really played it, there was a shadowy intruder. I woke shouting for help in the hospital, my heart racing from the terror of the figure that could only be the angel of death, and woke Kerryn who in her traditional role, comforted me when it was I who was supposed to comfort Kerryn.

That night someone died in the adjacent room, and we sat with the door sealed, our heads bowed and ears capped against the sounds of death - the ziplock bag, the muttering of prayers. It was no dream but a premonition of how our time would inexorably end, as it did literally yesterday, when me and my kids wrapped Kerryn up in a traumatic image that will never leave us.

It took Kerryn another 8 months to have her first death dream. Though I often saw her agitated at night, she woke one night in a sweat. It was after Gabe’s engagement party, in the lead-up to the race to get to the chuppa. She was crying.

Marky, she said. I dreamed we were at the airport at the gate ready to go overseas to America. Just as the gate opened I turned but it wasn’t your face anymore. It was my father Paul. By the time the doors closed I realised I didn’t have insurance. I panicked. I would never be able to get back to you. Days later she had another dream - she was on a train searching for her real father. Rachel was with her and they were being assaulted by a gang of rogues. One of the men unmasked himself behind a white veil. Kerryn was alone to fight the angel. She woke before the train reached its destination, terrified, unable to find her father. Days before her death she would say to me, don’t worry, I’m only going to America - you will find me.

When Kerryn got home after ten days in that first month, alive, though surely a contender for the Guinness book of records for answering all those loving text messages, she was offered all sorts of services from the Palliative care team. Never one to give up a deal, she accepted the offer of a biographer. The biographer would come for 6 sessions, write her life, and then compile it into a book.

I was skeptical from the outset, and made sure that the sessions were conducted in my study next to copies of The Fiftieth Gate. I think I was jealous - who was this stranger who would write my wife’s life?

Despite the most professional and compassionate efforts of the biographer, it was a disaster. Kerryn spent the first session answering one question - when were you born, and just cried and cried. She spent the second session talking about her parents, and barely got past pronouncing their names Sally and Paul. By the third she was despairing. My life is so boring, she would plead, there’s nothing to say.

And yet - Kerryn’s life was the stuff of high tragedy, a life so worth telling that the Shakespearean dramatics of it concealed from her the ability to speak of its significance and enduring impact.

Kerryn was born on 27 October 1960 into a new decade, the hippy era, but she was more of a 70s and 80s child in her dance style which I could never match. Her favourite film which she watched several times in the last months was The Big Chill, for it had all the ingredients for her - an opening scene with a funeral, a reunion of friends, lives full of unfulfilled promise, and more important than anything - great music. When I asked her what she wanted for her funeral she said a song.

A niggun you mean.

No, a song.

And she hummed it for me.

You can’t always get what you want.

Kerryn at the end of her life didn’t get what she wanted, a yearning repeated from an earlier stage of her youth. For this is the theme of her story - what she didn’t get in her life she dedicated herself to giving to others, mostly our children but also me. For a long time, she never spoke about her childhood - it was too painful, and for many it made her a closed book. Only with her cancer, and as a reaction to the silence that shrouded the divorce of her parents Sally and Paul, and the early losses of her youth, did she talk - publicly proclaiming at Gabe’s engagement the difficulties of her adolescence.

The memories of her family home in Miliara Grove with Ann, Bradley and Glenn were filled with happy stories - Kerryn recently reminded Bradley that despite the layers of bitterness that later overlaid their childhood, she remembers good times - Bradley pushing her on a swing in the park, triggering in him a deep love which had him calling his sister my angel in her final months; with Ann, her protector who would always carry her younger sister if she was upset — and of course with their baby brother Glenn. Yet those halcyon years where they worked in Fairways on Elizabeth St selling jeans, where marred by a bitter divorce that in Kerryn’s public words, made the War of the Roses look like a Garden party.

Let me say something at this point about me and Kerryn because it is part of the first act of her life. If family ties and the same school weren’t enough to link us in Grade 2, our classroom teacher might have sealed the deal. In the battle for pushy interventionist parents, of which Sally and my mother Genia were bantamweight matches, my mother got in first and refused my placement in Kerryn’s class with Mrs Yaxley, or Yackabom as we called her. That set off a domino effect where Kerryn went through a different trail of desks and to this day earned the distinction of being able to cite by rote Mrs Fuzy’s catechisms about the Renaissance and weather systems.

It was only in Form 12, as we called it then, that fate reunited us in Nana Newman’s biology class, again because of the intervention of my mother who insisted that a boy with half a brain must be educated in the sciences. Kerryn, was naturally gifted at these things, annoyed by my prankishness, and to my everlasting pride proved that in an era of gender discrimination girls at Scopus could show their mettle by topping HSC general maths. This of course marks the cerebral divide in my family - Kerryn balanced between left and right, and me fuzzy in some other spaced out zone.

Another moment of union took place in a photograph that Kerryn’s school friend Dianne recently brought us. We were visiting Mt Martha in 1977 and sharing a beach towel. I would like to tell my kids that this was the moment of adolescent passion but the reason I had forgotten that moment with Kerryn is that my eyes were fixated on the white bikini of another girl who I fancied at the time. After that, we parted ways - Kerryn starting medicine at Melbourne University, and me off for a year to Yeshiva where my hair was shorn, but grew back to Afro length in the second half of the year after I rebelled and became a Habo boy like her father.

I still recall Kerryn visiting Israel on Academy, the shorter version of the gap year away, and meeting her in a large hall. I approached her with interest - more than just the curiosity of a school reunion. There was something enigmatic about Kerryn even before she started wearing her modest outfits of every shade and cut of black - I associated her at the time with two of the books we had read in the same English class - The French Lieutenants Woman, and Marion from the Go-Between, women who harboured secrets and deep-seated, exotic, almost erotic mystery. This was around the time when I was discovering my own black box of secrets as a second generation Holocaust survivor - a collective story of myths and legends. Her black box of secrets were personal, visceral, something that she found difficult sharing with anyone.

For in addition to the divorce that had so embittered her life, her mother Sally had contracted breast cancer, a tumour that thankfully is totally unrelated to the randomness of Kerryn’s illness. This was the era when cancer was a secret disease, unspoken about. It was an awkward and foreign scene I encountered - something that our gorgeous Ralph and nurturing Tami had known from the outset but which for me was hard to decipher. Who was this Mr Young who had married Sally and was constantly baking apple cakes? Why didn’t anyone talk about the divorce? How was this woman living with cancer? Was she wearing a wig or was it her real hair?

In one of the many ironies, the man who supplied Kerryn with a wig before her first chemo had not only provided the same service for Kerryn’s Mum, but had even dated her once.

I met Kerryn again at a party I gatecrashed, and though my ego likes to say it was she who chased me, it was I who was smitten by her wit, her intelligence, and a poetic side whose output is lost somewhere in a drawer I am determined to uncover. We moved from friendship to love as her mother’s illness progressed.

There are so many memories I would like to recall - the late nights on Fitzroy street talking over pizza, parking the car on St Kilda beach and listening to cassette tapes of Steven Bishop singing Never Letting Go which I played to her only yesterday, and Jim Croce’s Time in a Bottle - how I wish I could get hold of that magic bottle now - and most vividly, racing passionately up a stairwell to the emergency fire exit in the penthouse where I crept past her mother’s sick bed into Kerryn’s bedroom. Kerryn’s Buba, a fierce matriarch, was kept in the dark about many things, including the premarital holiday we took to Noosa, allegedly with her girlfriends.

Like her parents, we never formally proposed, I remember sitting in a car outside Edinburgh and it was just decided. We went into my parents' bedroom and told them, and they were delighted not only that Kerryn was to be their daughter in law, but that I was marrying into a fine family. As for me, the son in law, I know that Sally loved me, but she didn’t quite know what to make of her daughter marrying an Arts student with a miniature crocheted kippa who dreamed of making aliyah. With her powers, she convinced me to see a psychologist - not as therapy, but with someone who might convince me to pursue a more practical career. I obliged for one semester out of obedience and a measure of self doubt, until I abandoned the experimental rats and returned to my set vocation.

Sally fought to make it to our chuppa in November 1982 but ended up in hospital soon after and almost died, only to recover by the sheer force of her will to make it months later to the birth of her first grandchild, Elliot. The story is legendary - she was here for the Friday night shalom zachor serving bobbes, but by the bris she was in hospital and died soon after.

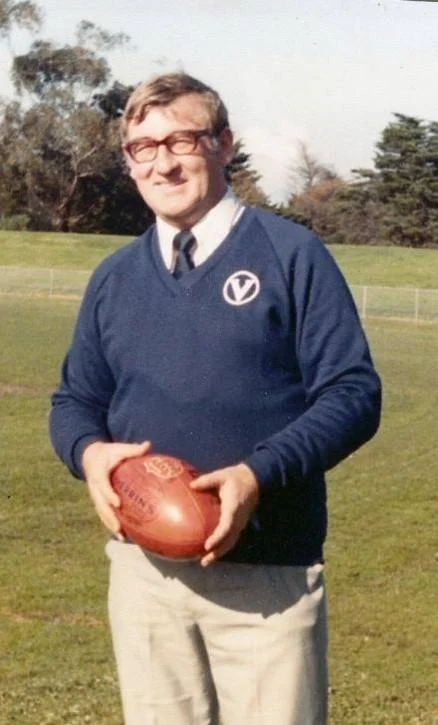

Eleven months later Paul, newly married, strong, with a deep voice that could scare his beloved Carlton players to kick winning goals, had a mild heart attack. He recovered from the elective surgery but after our first visit to the hospital we were called back to be told that he had bled internally and died. Within the space of a year of mourning, Kerryn, Ann, Brad and Glenn were orphaned.

Glenn was tossed from house to house - cared for by Ann and Ralph who parented him lovingly. When finally time permitted Kerryn to take a break from her final year of med - we went on our dream honeymoon with a chaperone - Glenn. Glenn proved to be great company through Vienna where we will always remember asking the waitress what Speck is, to which we were told as though we were unwelcome Jews who had wandered back to reclaim the city, Speck is Speck. Glenn, 8 years younger than me, also trained me for my UMAT test for entry into university, using his logical powers on the back of a Euro train to help me understand what happens if X sits next to Y in a rowboat and Z sits two seats across, who is sitting in the middle seat?

We returned from that trip for the continuation of a Machievallian drama - a fight over a will that I’d prefer not to talk about now, but which formed so much of the drama of Kerryn’s life. The result was a prolonged court case of QC’s, but our real shield then, as always, was Ann - fierce and protective of Kerryn, and Ralph, whose bond with Kerryn is so deep that we have spent many conversations on the phone crying in inappropriate places such as the Coles supermarket. I know, and you know, that Kerryn and I are forever grateful for your mature protection, and for introducing us in our Oxford days to the concept of a fax machine, which could only be found in a post office in far away Reading.

I’m not sure exactly where this long first Act ends - in a courtroom drama, in the loss of two parents - but Victor Hugo would have made much of it in the Wein version of Les Miserables.

I am only partially going to credit myself with Act 2 - the redemption of Kerryn, who in her own right became an accomplished doctor, yet was still locked in an unresolved drama. The key to our escape was to find refuge in another world. That world was fuelled by 1980s fantasies screened on our television sets such as The jewel in the Crown, from which we named our family company Mayapore because it sounded so exotic, and Brideshead Revisited. Guilt ridden Catholics we weren’t, but when faced with the choice of universities, we opted not for America but for Sebastian’s Oxford playground, which is maybe the source of the teddy bear fixation. I went ahead for a term whose name didn’t appear in my shtetl lexicon - Michaelmas - and left Kerryn for a semester at Caulfield hospital where she formed that special bond with my mother. Every lunch, she would go there and smoke cigarettes, or inhale hers passively, and at night she slept in Edinburgh in my brother Johnny’s room, perhaps fulfilling my mother’s dream of a doctor in the house.

I was only reminded of that episode by Kerryn recently, for one of the terrors I’ve had of losing Kerryn, is that I have delegated my memory to her much sharper mind. She is constantly reminding me of events I have forgotten, which I must now scribble down, such as the photographs on our wedding day being ruined and having to pose in full regalia the next day, or the 21st surprise party I organised for her on the banks of the Yarra. Amongst the 60s floral wallpaper in our family kitchen, my mother and Kerryn formed a bond which only strengthened through time, and though my mother will always say that a mother-in-law can never replace a mother, my mother was more than a mother-in-law and Kerryn more than a daughter. One can only weep at the tragic loss of my mother, a theme repeated from her own childhood, who though supported by Johnny and Anita whom she loves and love her, has lost - in her words - her best friend and lifeline to old age.

Act 2 opens on the train to Oxford, our first view of the spires and the Sheldonian Theatre, our entry into our new home at Wolfson college. Kerryn enrolled at Lincoln College and took up a research position at the Radcliffe infirmary, writing a paper with a distinguished scientist on inflammatory bowel disease. She was rewarded with a research trip to Basle, which I thought I deserved because it was the site of the first Zionist congress, and then she took an even better trip with our new found Canadian friends on a cordon bleu cooking class in Paris well before reality TV chefs become the rage. The lifelong friendship was recently reciprocated when our friends the Fish’s visited us and were blown away by how Melbourne breakfast culinary skills outdo bad Parisian coffee.