2 September 2025, Melbourne, Australia

Eulogy commences at 4.36 in above video

My grandfather was a man of many contrasts, a complicated man, but also a man of principle, strong-willed, tough yet caring and devoted. He lived according to principles that he created for himself, dedicated the first part of his adulthood to providing for his family after living through episodes that no one should, and spent the second half of his life in a foreign land, but one that he quickly embraced and came to love.

He was also a man of many names. His full Russian name was Gri-gory Yefimovitch Kats, his Hebrew name was Gershon ben Chaim HaKohen, but the name most of his Russian friends and family called him was simply Grisha. In the army he was Officer Kats and later Captain Kats, in the Communist Party he was Comrade Kats, in Australia he was either Gregory or Mr Kats.

In his more than 99 years, he was many things to many people, but deep down he was a family man, the last survivor of his generation and very resilient, in more ways than one. His kids called him Papa, his grandkids called him Grandpa or sometimes the Russian equivalent, Deda, and his great grandkids also called him Grandpa. One example of his devotion to family was when my sister Rachel was just a baby, and we all lived with our grandparents whilst our mother was in hospital. One evening, my dad was working nightshift, grandma and my aunt were out, I was staying over at a friend’s, so it was up to grandpa to babysit the six-month old. But he had the sniffles and as the evening wore on, got significantly sicker. In his old style way, he hadn’t told anyone he was sick and didn’t want to infect the baby, so he didn’t allow himself to enter the baby’s room and had a very miserable few hours trying to comfort the child from another room whilst blowing his own nose and feeling sorry for himself. In spite of everything, he kept to his principles. I suspect his wife and daughter got an earful when they got home, but it is a story he told proudly because it is one that shows the man he had become – a family man of principle.

But it wasn’t always that way. He was born on 10 June 1926 in Uman, Ukraine, a town that has now become synonymous with Jewish pilgrimages. In those days it was mostly populated by pious Jews, and his was one such family. He was the seventh child in his family, though two had died before he was even born. His parents, Chaim and Chaya – whose names are both derived from the Hebrew word for life – were well known in town, with his father acting as the Shamash of their local shule. By the time he was born, his parents were more ready to become grandparents than parents again, and in fact, just months after Grigory was born, the eldest of the family, his sister Roza, gave birth to her own son and also became his wet nurse. For the first few years of his life, he thought his sister was his own mother. Though they walked across the street to visit his parents on a daily basis, he initially thought they were his grandparents.

By the time of Grigory’s birth, the family consisted of Itzhak, who was known at home as Alex and is the one I am named after, who was 11 years older than Grigory; Nakhum, who was 17 years older, Yaakov, who was 19 years older, and Roza, who was 21 at the time of his birth.

In almost every way, Grigory was not only the youngest in his family, but sometimes felt forgotten. He grew up with his nephew Dimitry, who was virtually his twin brother, and life was mostly idyllic in their little hamlet in a very Jewish part of town, but he never quite knew where he fit in or what his place in society was. What he did learn however was that he had to be resilient and fend for himself. As a 6 or 7 year old, he survived a Stalin imposed famine, after which the extended family was split up, and for Jewish life in the shtetls of Ukraine, it was the beginning of the end. His family, like so many others, simply walked out of a house and town they had lived in for generations and only took what they could carry. For his mother, that meant all the family’s Mezuzahs and other mostly Jewish heirlooms, but by the time they arrived in Moscow, Jewish practice for all of them except his mother, also fell by the wayside. So much so that when Grigory turned 13 in 1939, he didn’t even have a Bar Mitzvah because of the impending war.

He was however very adventurous and enterprising. When they first arrived in Moscow, he was still constantly hungry but easily made friends. He was also a natural leader, so one day he led his group of friends to the woods behind their neighbourhood where they found an old farmhouse, though it looked abandoned. They did however find a few large barrels filled with freshly picked mushrooms. For hours, they filled their stomachs with the fungi, and came back for the next few days until all the shrooms were consumed. But from that day on, he developed a lifelong distaste for mushrooms because every time he saw them, they reminded him of famine, starvation and poverty. He vowed then never to be in a situation where he would have to again beg for money or food, and developed his own version of a moral compass.

Still in high school, he joined a pre-military academy, and one October day in 1941, after arriving at school, all the boys from his school, with just the clothes on their backs and their satchels in hand, were herded onto a train and taken north to Siberia. It would be more than a week before he could call home to tell his family where he was, and a few months before supplies arrived. They stayed there, in an abandoned coalmine till late 1944, undertaking schooling as well as military training, ready to be called up if and when required. But they were never required. Unlike others, in his time in Siberia he never got frostbite and didn’t even get sick. Sometimes he would pray to the god he no longer believed in to get sick, just so that he could end up in the warmth of the sick bay, but his prayers were in vain.

After school and after the war, he stayed in the army and went to Officer’s school, but on a brief visit back to his family home in Moscow in the summer of 1945, he discovered that only his mother, his sister with her family, and his brother Nachum had survived. Two brothers had been killed and his father had died just days earlier when he knew the war was finally over.

Grigory barely even had time to grieve because he literally had to leave the next day. One of his first postings as an Officer was to the town of Stanislav, later renamed Ivano Frankivsk, back in Ukraine. He rented an apartment and the Jewish landlady immediately took a liking to him. Apart from charging him a reduced rate, she kept asking if he was ready for a Shidduch because she was a matchmaker. He eventually agreed, and just weeks before his 20th birthday, he went on a date with Gizella Miller, known to everyone as Nina. She was from the Polish town of Yazlovetz, which is now part of Ukraine, and had come to Stanislav after the war. Within weeks they were living together, but his apartment was too small and she shared with members of her family, so Grigory, using all of his well-honed Chutzpah, negotiated his way to a small but nicely appointed one room apartment in a Jewish neighbourhood.

By April 1947, they were ready to get married, but with rabbis unavailable, synagogues closed and no money, they simply went to the registry office, brought along a Jewish couple from their building as witnesses, signed all the paperwork, had a L’Chaim afterwards, and with no fuss, then went back to work.

In December 1947 they welcomed the arrival of their son Yefim, also known as Chaim, named after Grigory’s father. Five and a bit years later, they had a daughter, whom they named Maya, after Nina’s father, Majer (pronounced Meir). For 17 years, Grigory had a career in the Russian Army, rising to the rank of Captain, and in that time, he and the family were stationed all over the country and even in Hungary for a time, following the revolution in that country. He even had a few near death experiences, but always pulled through unscathed, even when others around him got injured. He rose no higher than captain, in part because of insubordination. Though it wasn’t accidental or inadvertent defiance; he simply decided that some rules didn’t make sense to him so he refused to follow them. But he was very clever and cunning, using his Yiddishe Kop, to decide which rules he could get away with breaking. This was a trait that stayed with him his whole life.

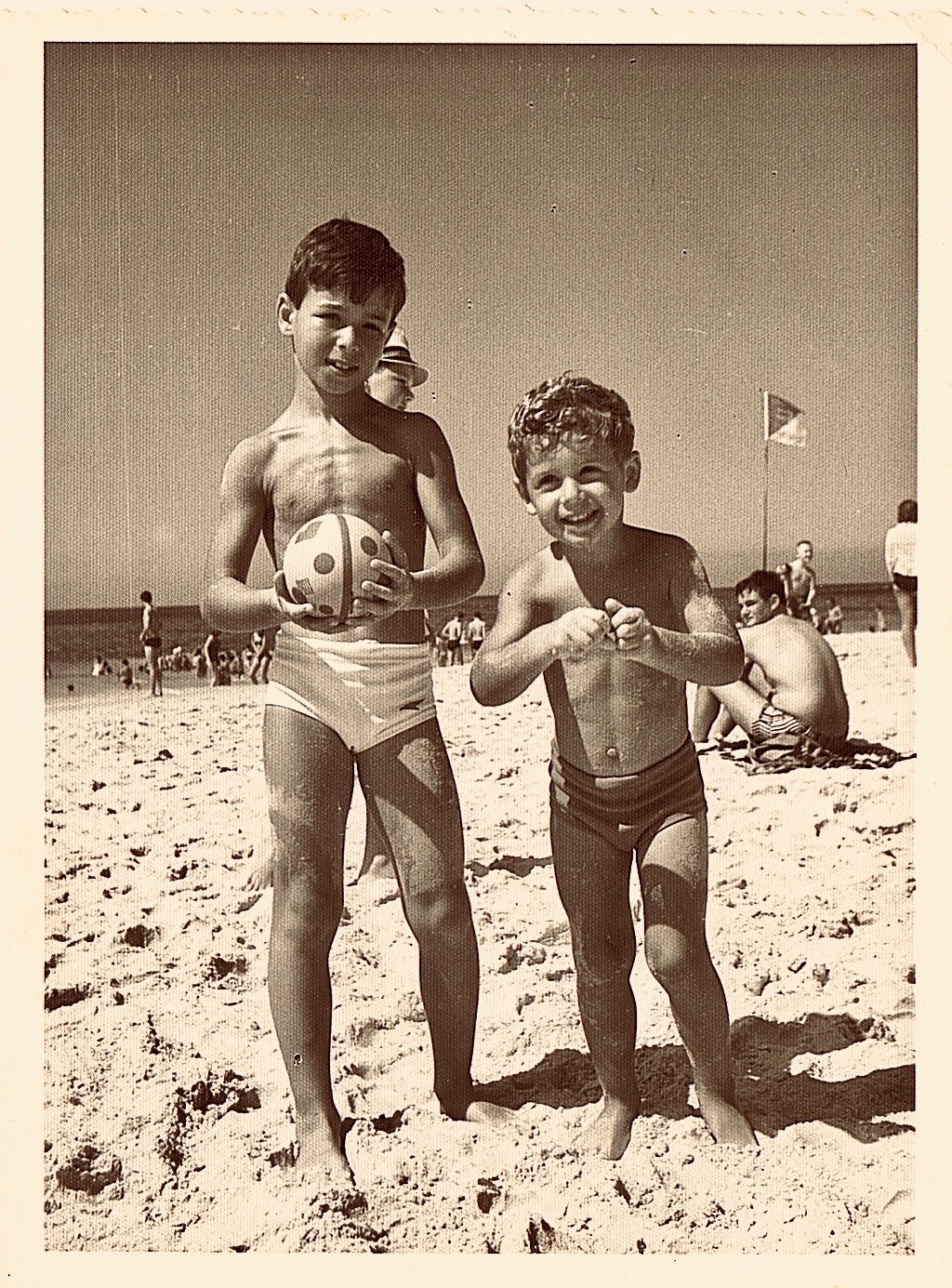

In the army Grigory was briefly a weightlifter and generally very good at sport. He even at one point also coached a basketball team. For someone so short, he was always a big character and everyone obeyed him. This served him well in his next career move as the manager of an elite rowing academy. Part of his role was to arrange their training camps around the country, and to manage their international travel when they went abroad for European competitions. This is when he used his cunning and Chutzpah again, and on many occasions got much better deals for his teams than anyone had before. He sometimes even gave his teams days off to explore the sights of the towns they were in, which was virtually unheard of.

In the 1970s, after Nina’s brother had come to Australia and his son was making plans to also leave mother Russia, Grigory would have none of it because he was still a proud member of the Communist party, though he also know that Jewish life in Russia was not ideal and both he and his son had lost job opportunities because they were Jewish. So although he was very reluctant to leave when his son, daughter in law and baby grandson left Russia, a year later he was also finally convinced to leave.

Grigory, Nina and their daughter Maya arrived in Melbourne in April 1980. Less than half a year later, their second grandchild was born and soon after Grigory found a role as the manager of a poultry shop on Chapel Street owned by the Fleiszig family. It wasn’t a kosher shop and he didn’t care, but working for a Jewish family always gave him comfort. For us as grandkids, it was also fun to visit the shop, to have plenty of chicken and fresh eggs at home, and to see him being in charge. He never shied away from hard work and carried heavy boxes on a daily basis. But he also knew how to have a good time.

Using his Chutzpah again, with almost no money and broken English, he managed to convince a bank manager to grant him a home loan without a deposit, and that apartment in Elwood was the site of very many Russian Jewish gatherings. In fact, Grigory and Nina became known as the Russian Jewish matchmakers of Melbourne, whilst their home was sometimes called the little restaurant on Avoca Avenue, such were grandma’s cooking skills and grandpa’s hosting skills. We had many adventures there as kids, including most of our Jewish festival celebrations growing up. Grandpa wasn’t always too keen about them, but grandma insisted and he mostly knew when to keep his mouth shut. It also became the place where grandma especially doted on all her grandkids, including her new granddaughter who was born in late 1989. For all of us grandkids, our grandparents were always loving, supportive and very generous. I even lived at my grandparents’ home for some months in the early 90s.

Grigory meanwhile became a fan of nice cars, and every few years he bought a new one. They used that car, together with other couples, to travel around most of Australia, with their favourite destination being the Gold Coast. Grigory could do that drive from Melbourne in a day and a half, and loved soaking up the sunshine and the playing the pokies with friends. They often also drove to Echuca just for the day to play the pokies across the border in NSW. They never won too much, but the adventure of it always excited Grigory.

By the time they arrived in Australia, Grigory had completely forsaken his commitment to Communism. Their one and only overseas trip was to Israel in 1993. It was a dream come true for Nina and an eye opening experience for Grigory. Both of them loved the place but didn’t understand it. But for Grigory especially, that trip cemented his anti-Communism stance, so much so that he became a conservative voter.

He retired in 1998, just months before his beloved wife died. It is probably not a coincidence that she died on 27 August, and he died on 29 August, both within the Hebrew month of Elul. After her passing, he was never quite the same. On many occasions, he would say that he wished she was with him to enjoy their retirement together. He had two short-lived relationships in his later years, but it was clear he still missed his wife. He would also say, whenever we called and asked him how he was, now that he was alone, that he was “Still Alive.” That became his catchphrase, and even he would sometimes joke about it.

In many ways, although he retired from the army, the army never left him. He was always a pedant, extremely punctual, a resilient, determined and stubborn man, who said what he thought and usually didn’t concern himself with the repercussions of his words. As he aged, these traits became even more obvious. He didn’t have a lot of hobbies, but meeting his friends was one, and together they settled into a well-honed routine of going to his favourite coffee shop on Centre Road and having coffee and cake there every day at 11am. He was also a pessimistic optimist who believed he would survive to the next day, but just in case, went shopping every day whilst on Centre Rd and only bought what he need for tomorrow. One time, ahead of a public holiday, Rachel and I called him to ask if we could join him the following day for coffee. He loved the idea, but when we said we could be free from 10, he said, “Why 10? Coffee time is at 11.”

The beginning of his own demise started with the death of his wife and increased significantly after the death of his daughter eight years ago. Just before that point he stopped driving and started to walk with a stick. He was physically and mentally much older, but remained fiercely independent, and even when we found carers for him to look after him at home, he rejected some of them – unsurprisingly all the male ones – because they didn’t conform to his standards. Even in the last few years, as his dementia increased and so did his falls, he still didn’t want to go into care and continued to have very strong views about the world. He also wanted to ensure that when the apartment he bought after grandma died was finally sold, that we would get the best value for it. Thinking about his family legacy was never far from his mind. At this point I want to publicly thank the carers and staff at Jewish Care who looked after him.

The family members that he liked and still recognised were the ones that he cared about right up to his final days. And those final days, though they came quickly in the end, there were at least five occasions between Covid and last week, when there were calls to say that he was on his final legs, but somehow his will to live was strong. Even just a couple of months ago, he repeated his commonly articulated phrase, that ‘It’s very hard to die.” And in his case it was certainly true. But in the end, once the palliative treatment began last Wednesday, on 27 August – the same date that grandma died – it only took two days. Now he has been reunited with his dear wife and they will be buried together in the double plot that he bought many years ago.

We were all blessed to have him in our lives for as long as we did, and he certainly led a long, adventurous and fruitful life, one that we will never forget and one that we will take great appreciation from.

Yehi Zichron Baruch – May his memory be a blessing