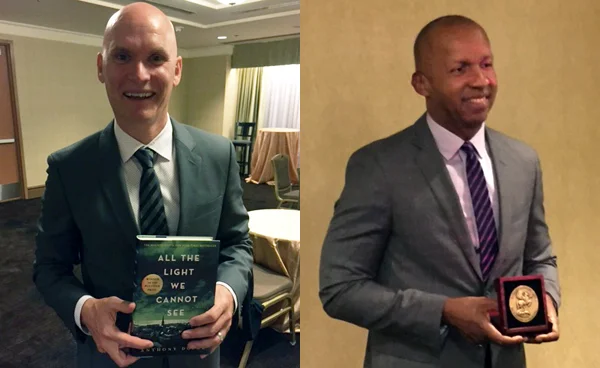

27 June 2015, American Library Association conference, San Francisco, USA

Thank you. I'm pretty overwhelmed by this...I really want to thank all of you for creating a space where something like this could happen to somebody like me. I'm really, really grateful to the selection committee, to all of you.

I had a very close relationship with my grandmother. My grandmother was the daughter of people who were enslaved. Her parents were born into slavery in Virginia in the 1840s. She was born in the 1880s, and the only thing that my grandmother insisted that I know about her enslaved father is that he learned to read before emancipation, and that reading is a pathway to survival and success. So I learned to read. I put books and words in my head and in my heart, so that I could get to the places that she needed me to go.

I'm thinking about my grandmother tonight, because she had these qualities about her. She was like lots of African American matriarchs. She was the real force in our family. She was the end of every argument. She was also the beginning of a lot of arguments! She was tough, and she was strong but she was also kind and loving. When I was a little boy, she'd give me these hugs, she'd squeeze me so tightly I could barely breathe. And then she'd see me an hour later and she'd say, "Bryan, do you still feel me hugging you?" And if I said no, she would assault me again!

She left Virginia at the turn of the century, like millions of African Americans who were fleeing terrorism and lynching and racial violence, and she moved to Philadelphia. Because I still lived in the country and grew up in the country, she worried about me when I would come and spend time with her, because there were so many people she didn't know. I would go outside and make new friends, and every now and then she'd be really critical about some of the people I was hanging out with. She'd say, "Now Bryan, be careful about the people you hang out with. Be careful of who you spend time with because people will judge you by the company you keep."

Being here, among these amazing writers, extraordinary writers, being here with my childhood idol, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, being here in a room full of librarians who do such great work, I hope my grandmother is watching. I can say to her, "Mama, please, I hope they judge me by the company that I keep."

I think there's a phenomenon that's really changed this country, such that I couldn't help but be compelled to write about it. It's been my life's work. The United States is a very different country today than it was 40 years ago. In 1972, we had 300,000 people in jails and prisons. Today we have 2.3 million. The U.S. now has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. There are six million people on probation and parole. There are 70 million people with criminal arrest records, which means when they apply for a job or try to get a loan, they're going to be disfavored.

The percentage of women going to prison has increased 640% in the last 20 years. 70% of these women are single parents with minor children. When they go to jails and prisons, their kids are scattered. And you are much more likely to go to prison if you're a child of an incarcerated parent.

And we've done some horrific things in poor and minority communities through a misguided war on drugs and our criminal justice policies. Today, the Bureau of Justice reports that 1 in 3 black male babies born in this country is expected to go to jail or prison. That was not true when we were born in the 20th Century. It was not true in the 19th century. It became true in the 21st Century. Children have been condemned to die in prison. There are15 states with no minimum age for trying children as adults. We’ve created a world where there is despair, where people are living on the margins of our society.

I wrote this book because I was persuaded that if people saw what I see, they would insist on something different. And that's what's powerful about books. That's what great about the library. Getting people closer to worlds and situations that they can't otherwise know and understand. I think there's real power in that. And that's what books can do.

I'm a product of the Civil Rights Movement. I grew up in a community where black children couldn't go to the public school system. I started my education in a colored school. And then lawyers came into our community and made them open up the public schools and because of that, I got to go to high school and I got to go to college. There were no high schools for black kids in my county when my dad was a teenager. So proximity means something to me. I want to get people closer to this world, where there is a lot of suffering. Where there's a lot of despair.

The other thing that books do is that they change the narrative. And for me that's what's great about writing, that I have an opportunity to change some of these narratives. I want to change the narrative in this country about mass incarceration as excessive punishment. I'm persuaded that a just society, a healthy society, a good society, can't be judged by how it treats the rich and the powerful and the privileged. I think we have to judge ourselves by how we treat the poor, the incarcerated. And I think literature has the ability to accomplish that narrative shift.

Our system has been corrupted by the politics of fear and anger. We've had politicians competing with each other over who can be toughest on the crime for 40 years and the consequences of that have been absolutely devastating.

I go into communities and talk with 13 and 14 year old kids who tell me that they don't believe that they're going to be free or alive by the time they're 29. And that's not because of something they've seen on TV, but because of what they see that happening every day in their lives and their families and their communities. That despair has to be changed.

We need to change the narrative in this country about race, and poverty. We're a country that has a difficult time dealing with our shame, our mistakes. We don't do shame very well in America, and because of that we allow a lot of horrific things to go unaddressed.

I don't think we actually understand what the legacy of slavery did to this country. The great evil of American slavery for me was not involuntary servitude. It was not forced labor. The great evil of American slavery was the narrative of racial difference we created to justify that institution—the ideology of white supremacy.

We made up these things about people of color, and we use them to legitimate an institution. The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment did not deal with that narrative. And that's why slavery didn't end in 1865. It just evolved. It turned into decades where we had terrorism, and lynching, and that lynching and terrorism has had a huge impact on this country.

The demographic geography of America was shaped by lynching and terror. You've got African Americans in the Bay Area of Oakland and Los Angeles, and Cleveland, and Chicago, Detroit, Boston, New York, and they did not come to these communities as immigrants looking for new opportunities. They came to these communities as refugees and exiles from terror. If you know anything about the needs of refugees, you know there are issues you have to address if you're going to create opportunity, and hopefulness. And we're not doing that . Because the narrative hasn't evolved.

Even when we talk about Civil Rights—I'll be honest—I'm critical of the way we're dealing with it. We're celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Civil Rights Movement. And we're too celebratory. I think we're too superficial. I hear people talking about the Civil Rights Movement, and it sounds like a three-day carnival. On Day one, Rosa Parks didn't give up her seat on the bus. On Day two, Dr. King led the march on Washington. And on Day three, we just changed all these laws.

If that were true, it would be a great story. But it's not true. The truth is, for decades we have humiliated people of color in this country. For decades we excluded people from voting. We denied people the opportunity to get an education. We belittled them. We burdened them. My parents were humiliated every single day of their lives. Every time they saw "colored" signs. And we have to talk about that. I don't think we'll get where we're trying to go until we change that narrative.

Truth, and reconciliation. If you go to South Africa, you can't go very far without hearing somebody talk about the process of truth and reconciliation. Go to Rwanda, and they will tell you that genocide will not be overcome without truth and reconciliation. Go to Germany, and in Berlin, you can't go 100 meters without seeing the stones that mark the places where Jewish families were abducted and taken to the concentration camps. They want you to reflect solely on the history of the Holocaust.

In this country, we want the opposite. We don't want anybody talking about race. We don't want anybody talking about inequality. We don't want anybody talking about poverty. And that legacy has created a world of mass incarceration and excessive punishment.

Another thing for me, is that the books I've written have made me be hopeful. They've made me believe things that I could not otherwise see. And that's the great gift that I think all of you give people by opening up libraries and spaces where children can dream. I'm absolutely persuaded that you have to believe in things that you can't see. I never met a lawyer until I got to law school. I never imagined I would be an author. But it's happened because there is something fundamentally compelling about believing in things that we know to be decent and true.

I believe in really simple things. I believe that each person is more than the worst thing that they've ever done. I think that for you. I think that for my clients. I think that for everybody. Even the people jailed and in prison. I think if you tell a lie, you're not just a liar. I think if you take something that doesn't belong to you, you're not just a thief. I think even if you kill somebody, you're not just a killer. And the other things you are have to be recognized, and addressed, and discussed.

I also don't believe that the opposite of poverty is wealth. I think we talk too much about money in America. I believe that the opposite of poverty is justice. And until we learn more about what justice requires, we won't actually do the things we need to do.

I'm excited and really gratified to accept this award. I'm humbled to be in this space. I'm actually encouraged that there's a metric system out there for people like me where somebody like me, who does what I do, can be encouraged and affirmed. It's been incredibly moving. I can't tell you what you've done for me tonight.

I'll end with this story. I actually have been thinking a lot about the metric systems we use to reward the things that we care most about. I was nurtured by a community of people who were activists, and who believed in things, even though they didn't have very much. And they taught me that if I stay true to that metric system, good things will happen. At times, I have doubted that. But tonight I feel it.

Someone who taught me this lesson more than anybody else was an older man at a church where I was giving this talk. He was in a wheelchair. And he came to the back of the church, and he was just staring at me while I spoke. I didn't know him. But he was staring at me with this very harsh look on his face. He just kept glaring at me. I couldn't figure out why he was looking at me so sternly.

I got through the talk and when I was finished, people were very nice, very polite. But that man kept staring at me. Finally, after everybody left, he got a little kid to wheel him up to me. And this older man, in his wheelchair, got right in my face and put his hand up and he said, "Do you know what you're doing?"

I didn't know how to respond. He asked me again. "Do you know what you're doing?" I stepped back and started mumbling something. One last time, he said: "Do you know what you're doing?" I just stood there. And then he said, "I'm going to tell you what you're doing. You're beating the drum for justice."

I was so moved. I was also really relieved!

And then he said: "You keep beating the drum for justice." And he grabbed me by the jacket and pulled me into his wheelchair. “I want to show you something," he said.

He turned his head. “You see this scar behind my right ear? I got that scar in Green County, Alabama, in 1963, trying to register people to vote."

He turned his head again. “You see this cut down here at the bottom of my neck? I got that in Philadelphia, Mississippi, 1964, trying to register people to vote."

He turned his head one more time. "You see this dark spot? That's my bruise. I got my bruise in Birmingham, Alabama, 1965, trying to register people to vote."

Then he looked at me and said, "Let me tell you something, young man. People look at me, they think I'm some old man sitting in a wheelchair covered with cuts and bruises and scars. I'm going to tell you something. These aren't my cuts. These aren't my bruises. These aren't my scars. These are my Medals of Honor."

I never, ever, ever imagined that going to Death Row, spending time with the condemned, representing children who had been crushed and broken by suffering and trauma, going into poor communities, day in, day out, that the cuts and scars and bruises that I was getting would turn into a medal of honor. But tonight you've made that real. And I'm very grateful. Thank you

Buy Bryan Stevenson's amazing book here.