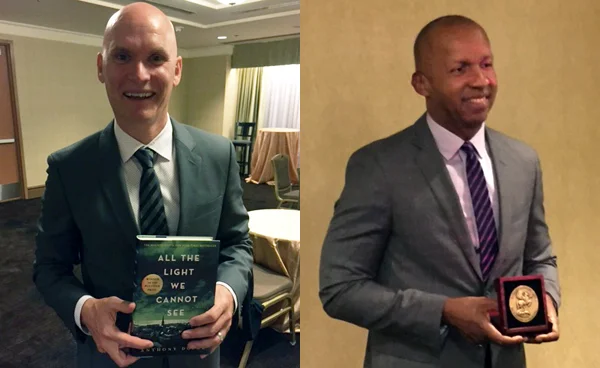

1 November 2015, Schuster Performing Arts Center, Dayton, Ohio, USA

Thank you. What a special night. Karima, thank for the incredibly beautiful introduction. I'm really overwhelmed to be here, to be in this space with so many extraordinary people, so many extraordinary writers.

My grandmother was the daughter of people who were enslaved. She was born in Bowling Green, Virginia, in the 1880s. Her father was born in slavery in Virginia in the 1840s, and when I was a little boy my grandmother was always in my ear about her experience of growing up enslaved. And my sister's here with me, and our grandmother had a profound impact on us. When I would see my grandmother, as a little boy, she'd come up to me and she'd give me these hugs, and she would squeeze me so tightly I could barely breathe. And then if I saw her an hour later she'd say to me, she'd say, 'Bryan, do you still feel me hugging you?', and if I said no, she'd assault me again, and I quickly learned to tell my grandmother, 'Mamma, I feel you hugging me all the time', and it was just this way that she had about her.

And when we got older, my mother would take my sister and I to Philadelphia, she fled Virginia at the turn of the century because of the lynching, and the trauma, the terror that was ravaging that part of the country, and she'd started her life in Philadelphia, raised my mom there and when I would go and visit her, when we would go and visit her as children, I would always be kind of struck by the city, 'cause we grew up in the country, and as I got older I got more courageous and I would explore different parts of the city and I'd venture farther and farther away from where she lived, and she would keep an eye on me, and every now and then she would warn me about things, and one day I'd been out with some boys I'd met on the street and we'd been kind of gone a long while and she was worried. When I got back, she told me, she said, 'Now you need to watch yourself, because people will judge you by the company you keep. I trust you, but I don't know those other boys, You just need to remember that people will judge you by the company you keep.'

And my greatest regret tonight is that my grandmother is not here, because if she was here, what I'd do is I would point to Gloria Steinem, I would point to Josh (Weil), and I would point to Jeff (Hobbs), and I would point to these amazing writers who have won this award and I would ask my grandmother, 'Mamma, do you still think it's true that people will judge me by the company I keep?'

Because if it is true, then that is prize enough in and of itself, I'm so thrilled, and to become part of this community, to become part of this family of authors and writers and thinkers and believers in the power of literature.

You know I wrote my book because I really think there are four things that we can all do, to create more peace, to create more justice.

I wrote my book because I'm persuaded that we all have to find ways to get proximate to the things that are creating tension, and conflict, and suffering, and inequality.

I believe there is power in proximity, I think when we choose to get closer to the spaces in our community where there's suffering and inequality, when we actually position ourselves in places where there's been abuse of power and we become witnesses, that's the only way we can actually create more peace.

You can't problem solve it from a distance. We get things wrong in politics because we're trying to make up solutions to far away, you hear things when you're up close, you see things when you're up close, there's power in proximity.

I'm the product of someone's choice to get proximate. My sister and I started our education in a 'coloured' school. In a community where black children were not allowed to go to the public schools. Lawyers came into our community and made them open up the public school in compliance with Brown vs. Board of Education. Because of that I got to go to high school, I got to go to college, I got to go to law school. And when I was in law school I got to meet people who were on death row, literally dying for legal assistance and that proximity not only told me that there was work that needed to be done, but it showed me that I had power. Not power rooted in intellect, not power rooted in talent or gift, but power rooted in witness. And when you get proximate, you can become a witness to the tactics, and the strategies and the power of peace. And I believe in proximity, and I think we can all get proximate, we don't have to live in another world, we don't have to be a writer, we can just be proximate in the spaces where there's trouble and discord and unhappiness and suffering.

The second thing that I'm persuaded that we have to do and it's the reason why I wrote this book, is that we have to change the narratives that sustain inequality. Mass incarceration in this country was created by bad policies. We decided to deal with drug dependency as a crime issue rather than a health issue, we let our politicians begin to promote the politics of fear and anger. They've been competing with each other over who can be the toughest on crime. We created mandatory sentences, we did a lot of just damaging things.

But the real threat is the narrative, that idea that we should stay angry, that we should stay afraid, and I will tell you whenever a country, whenever a community makes decisions rooted in fear and anger, you will abuse other people. Fear and anger are the enemies of peace, and we have to fight against fear, we have to fight against this judgement that is rooted in anger and bigotry, and that narrative has to change.

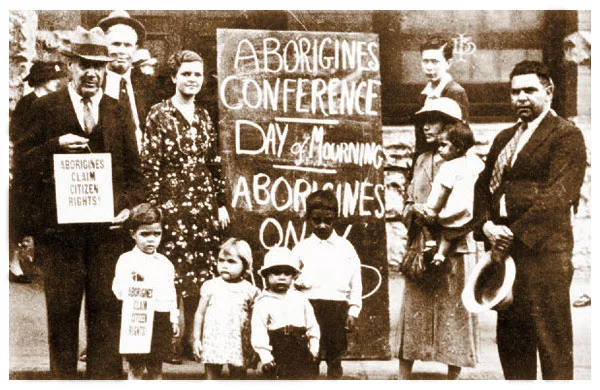

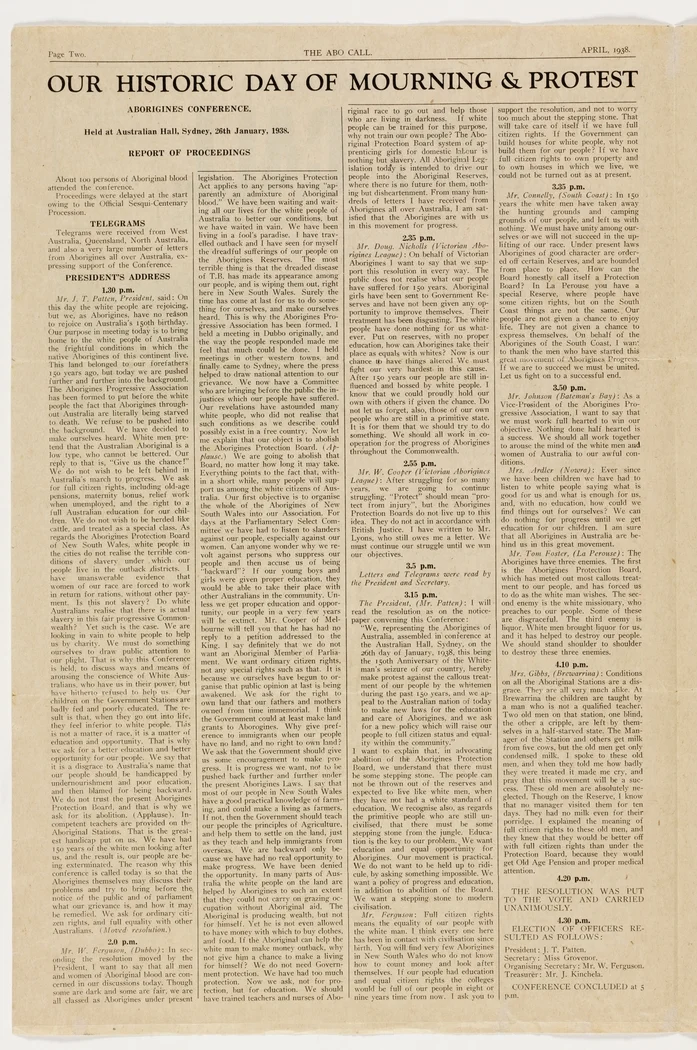

I also think we have to change the narrative in this country about race. We've all been infected by a disease, this disease rooted in a narrative of racial difference. For me, the great evil of so much of what we are dealing with is this narrative and we have to change that narrative, we have to talk about the things we haven't talked about. I love Margaret's book because I believe we have to talk about slavery in America. We never had the conversation we should have had a hundred years ago, fifty years ago, because of it we are still burdened by this legacy that slavery has created. The great evil of American slavery for me was not involuntary servitude, was not forced labour. The great evil of American slavery was the narrative of racial difference, we created. The ideology of white supremacy we created to legitimate slavery. And we never did anything about that.

If you read the 13th Amendment, there's nothing in there about the narrative of racial difference. There's nothing in there about the ideology of racial - of white supremacy. And because of it, I don't believe that slavery ended in 1865. I think it just evolved. It turned into decades of racial hierarchy, and terrorism, and it resulted in lynchings and terrorism. Older people of colour come up to me sometimes and said, 'Mr. Stevenson ...' I get angry. When I hear somebody on TV talking about how we're dealing with terrorism in the first time in our nation's history after 9/11.

We grew up with terror, we to worry about being bombed and lynched every day of our lives. The demographic of geography of this state, of this nation was shaped by terror. The African Americans in Dayton and Cincinnati, and Cleveland, and Chicago, and Detroit, in Boston and New York did not come to these communities as immigrants looking for opportunities, they came to these communities as refugees and exiles from terror, and we haven't told that story.

Even civil rights, I get worried, I hear people talking about the civil rights, and we're so celebratory. And I worry about that, because we haven't dealt with the fact that for decades in this country we humiliated people of colour, we burdened people, we battered people, we excluded people. My parents were humiliated every day of their lives. Every time they had to see that sign that said 'white' and 'colour' there was an injury. We told black people you're not good enough to vote, you're not good enough to go to the schools with us, and we haven't dealt with that.

I think we needed truth and reconciliation at the end of the civil rights movement and we didn't do it. And because of that we are now burdened with the presumption of guilt that follows too many people. it's why that young man was shot and killed in a Walmart. It's why there is such angst and insecurity and we have to change the narrative. We can't get to peace until we understand the narratives of bigotry and exclusion.

But, the third thing for me is hope. I wrote this book because I'm ultimately persuaded that we have to be more hopeful about what we can do. I believe things I haven't seen, I have to. I believe that we've got to find ways to resurrect our hope. I am persuaded that hopelessness is the enemy of peace. It is the enemy of justice. Injustice prevails where hopelessness persists, and if we don't find ways to stay hopeful – the society that is most dangerous is the society made up of people who don't think that things can get better, who don't believe that they have the power to make a difference. That is the recipe for abuse of power.

And I wrote this book because I am persuaded, if we can get people to choose to get proximate, change narratives, and do hopeful things, we can create more peace.

But the final thing, the fourth thing that I wrote this book about is because I believe that if we really want to create more peace, if we really want to create more justice, we can't just get proximate, we can't just change narratives, we can't just be hopeful, we've got to do uncomfortable things, that the fourth thing

You cannot create peace, you cannot create justice, by only doing what is comfortable or convenient. I've read, I've studied, I've looked all over the world to find instances where oppression ended, where inequality ended, and every time I've read and studied, it ended when someone chose to do something uncomfortable. Doing difficult things is hard. I know it. But, I believe it's necessary and what a great community like this can do, when it chooses to do it, is change the world. I think there's a different metric system for those of who really believe in peace, who believe in the power of literature to sustain peace, and it was taught to me by this older man, I'll end with this.

This older man, I was giving a talk in a church some years ago, and this older man came into the church and he was sitting in a wheelchair, staring at me the whole time I was talking, he had this very stern, angry look on his face. And I, and I was worried about him, because he looked at me so intensely, he had me a little unnerved. And I was trying to get through my talk, but he kept staring at me. And I got through the talk and people came up and they were very nice, they were very appropriate, but that man kept staring at me. And when everybody else left, he got a little boy to wheel him up to me in the middle of this church. And this older black man in this wheelchair came up the isle of that church with this stern, almost angry look on his face, and when he got in front of me he put his hand up and he said, 'Do you know what you're doin'?' And I just stood there. And he asked me again, he said, 'Do you know what you're doin'?' And I stepped back and I mumbled something. I don't even remember what I said, and he asked me one last time, he said, 'Do you know what you're doin?', and then he looked at me and he says, 'I'm gonna tell you what you're doin'.' And that older black man looked at me, he said, 'You're beating the drum for justice. You keep beating the drum for justice.' And I was so moved, I was also really relieved, 'cause I just didn't know.

Then he grabbed me by my jacket and he pulled me into his wheelchair, he said, 'C'me here, c'me here, c'me here, I wanna show you something.' And this older man turned his head, he said, 'You see the scar behind my right ear?', he said, 'I got that scar in Green County, Alabama in 1963 trying to register people to vote.' He turned his head, he said, 'You see this cut I have down the bottom of my neck? I got that cut in Philadelphia, Mississippi, 1964, trying to register people to vote.' He turned his head, he said, 'You see this dark spot, see that bruise? I got my bruise in Birmingham, Alabama, 1965, trying to register people to vote.' And then he looked at me, and says, 'I'm gonna tell you something, young man,', he said, 'People look at me, they think I'm some old man, sittin' in a wheelchair, covered in cuts and bruises, and scars', he says, 'but I'm gonna tell you something. These aren't my cuts, these aren't my bruises, these aren't my scars,' he said, 'These are my medals of honour'.

And I will tell you something, that I believe that when we do the things that are necessary, when we get proximate, when we change narratives, when we stay hopeful, when we do uncomfortable things, we'll get nicked a little bit, we'll get cut, but, that's how we create peace. I believe in really simple things. I believe that each person is more than the worst thing they've ever done. I think of someone who tells a lie, they're not just a liar. I think of someone who takes something, they're not just a thief. I think even if you kill somebody, you're not just a killer. And the other things you are, is what a just society must find.

I also am persuaded that the opposite of poverty is not wealth, we talk too much about money in America. I believe that in this country and in communities like this, the opposite of poverty is not wealth. I believe the opposite of poverty is justice.

And finally, I believe that when I come to Dayton, and when I come to Ohio, when I go anywhere in this country, we can't really measure how we're doing, our character, our commitment to justice, our commitment to peace, by looking at how we treat the rich, and the powerful and the privileged.

I think you have to judge a community, it's character, it's commitment to justice, by looking at how it treats the poor, the incarcerated, and the condemned. And tonight, by shining this wonderfully warm, restorative light that you have created here in Dayton with me, tonight by embracing me and the kind of work that I do, you've made me believe that the times I've been nicked, the times I've been cut, the times I've been scarred have not been times that have been wasted, but you've made me believe that through your light, and yes, maybe through your embrace and through your love, those nicks and cuts and scars can be turned into something that is truly honourable.

And for that, I cannot tell you how grateful I am, I cannot tell you how honoured I am, and I cannot tell you I appreciate this moment and this recognition. Thank you all very, very much.