23 March 2015, Grass Roots Sports Club, Melbourne, Australia

I want to talk today about the most moving game of football I saw last year. To explain why it moved me as it did I have to go back to 1987 and a trip I made to Yuendumu, a couple of hundred ks north-west of Alice Springs. Yuendumu is where Liam Jurrah comes from but this was before he was born.

I went to see a traditional Aboriginal football carnival with 32 communities competing. That weekend was to have a great impact on me but I only have time today to tell you about a couple of the things that happened.

The first was when I arrived, driving in past hundreds of humpies made from tin and sackcloth, trying to absorb the fact that this was my country, Australia, and I saw a white woman -- who turned out to be the community nurse, surrounded by a group of initiated tribal men. Without thought, I approached her and initiated conversation talking about the 32 teams on the way. And she said 26. And I said I was told 32 and she hissed out the side of her mouth, 'don’t you understand it’s men’s business.'

And, for the first time, I did. I understood I was on Aboriginal land. Also for the first time I sensed the presence of what Aboriginal people call THE LAW. The Law operates with dreadful certainty and that weekend the Pitjintjatjara were initiating their young men in the dreaming paths and where the dreaming paths crossed roads it was the roads that closed because with the group was the much-feared Red Ochre Man, the Pitjinjatjara lawman who still employed the death penalty.

That weekend, I met a feller called Ian King. He had played cricket for Queensland –- his mother was Aboriginal, his father was a black GI who came here during World War 2. He was wandering Australia trying to better understand his Aboriginality and he was the person who told me there was a connection between Aboriginal dance and Aboriginal football.

Aboriginal dance is about summoning spirits, particularly of the creatures that inhabit this land. Aboriginal football, the game we call marngrook, was played on a totemic not a tribal basis. The totems for Melbourne, for example, are the eagle and the crow. I am no expert in this area but I do know that the story of Bunjil the eagle goes a long way into western Victoria. Because the game was played on a totemic basis, the eagles team would have players from different tribes, players who might have previously been involved in tribal wars.

In this way, the game served to bring people together.

The final story I will tell you about the Yuendumu weekend is that on the third day, shortly after the grand final started, a child ran among the crowd saying he had seen the Red Ochre Man.

Within a few minutes the place was deserted and the ball was left sitting in the red sand.

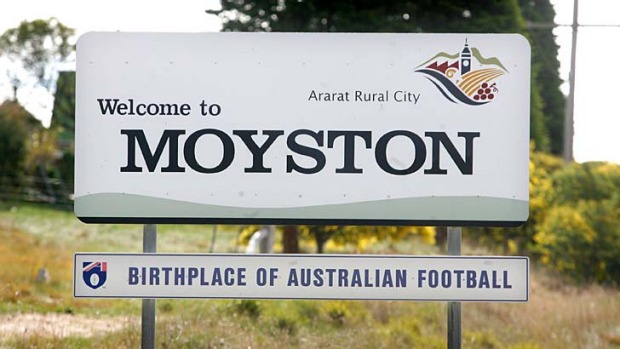

What I’m asking you to do now is take that Aboriginal consciousness which I have tried to suggest to you and transport it to the year 1840 and a place in western Victoria called Moyston because, back then, it was out there too.

It was that large, that vivid, that strong.

And in the middle of it is a white kid called Tom Wills. His father Horatio has been the first white settler in the Ararat region, arriving in or around 1838.

I can’t tell you exactly who Tom Wills was any more than I can tell you exactly who Ned Kelly was, but there are some things I can tell you. I can tell you that while I’ve met whitefellers who can speak Aboriginal languages, I’ve never met one who grew up speaking the Aboriginal language for the place he grew up in.

As I said to a Jewish audience at the Melbourne Writers’ Festival, that’s like the difference between speaking Hebrew and English in Israel.

Moyston was in the lands of the Tjapwurrung. Tom Wills knew Tjapwurrung songs, he knew Tjapwurrung dances. He grew up playing with Tjapwurrung kids. Of course, he played their games; his whole life was about playing games.

What I want to talk about today is not so much Tom Wills as Moyston but, in case anyone hasn’t heard it, I will give a brief sketch of Tom’s amazing and ultimately tragic life. The Wills family believe they are an illegitimate branch of the Churchills, their convict forebear having been saved from the gallows by an eminent Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough.

The convict’s son - Tom’s father, Horatio - was a forceful, charismatic man who did many remarkable things including sending his second son to Germany to become a vigneron because he predicted Moyston would have a wine industry.

But he was also the son of a convict and uneducated. He sent Tom to the Rugby school in England. Tom returned six years later as a dandy with the reputation of being one of the best young cricketers in England.

Under Tom’s captaincy, Victoria beat New South Wales for the first time, that match being played in Melbourne in 1858. In the euphoria that followed Tom was appointed secretary of the Melbourne Cricket Club. Wanting to defeat New South Wales in Sydney, he urged the formation of a football competition to keep hi cricketers fit during the winter months and made the radical proclamation that we should have a game of our own.

And thus the game we call AFL was born.

Meantime, however, Tom’s father was not happy. Having sent his son to Rugby to become a great political leader, he found himself with a son who was only interested in games. Horatio’s political career had stalled because he was the son of a convict so he decided he would head out again to the frontier, which now lay in Queensland, and take Tom with him and make a man of him. They walked into the middle of a land war, their neighbouring squatter having shot Aboriginal people the week before they arrived.

Horatio Wills believed he could persuade the local Aboriginal people of his friendly intentions. Tom tried to warn him. The father brushed the son aside then had a premonition that death was imminent and sent Tom back down the track to get a dray. While he was away, the blacks attacked – it was the biggest killing of whites by blacks in Australian history. 22 dead - men, women, children. In retaliation, the whites and the native police killed possibly ten times as many blacks – again, men, women, children. Tom stayed up there, caught in the middle of a land war, for two years. His family, who believed Tom’s abilities in life were limited to bats and balls, sent up his younger brother to oversee him.

Tom returned to Melbourne like a Vietnam veteran – everybody had some idea of the war being fought at the frontier but no-one knew what he did about its reality. Then, in 1866, five years after his father was murdered by Aboriginal people, Tom Wills was at Lake Edenhope, coaching the Aboriginal cricket team that became the first Australian cricket team to tour England.

The Aboriginal team led the MCC on the first innings at Lord’s. With Tom in the team, they almost certainly would have won. He would have been the first Australian captain to have won at Lord’s and his life would have made some sort of sense.

But Tom lost the political battle over control of the Aboriginal team just as he lost every political battle of his life. Tom’s attitude was “I’m the best - why wouldn’t you do what I say?” The attitude of bodies like the committee of the Melbourne Cricket Club was, “You’re our employee – you’ll do as wesay”.

He had been drinking since his Rugby days. By now, he was a desperate alcoholic. Even so, according to an official history of the Carlton Football Club, in 1879 Tom managed to persuade a majority of delegates at a national conference inAdelaide that now was the time for the game to go international. Games can’t travel internationally until they’re codified, until they exist in a set of rules that can be written and read. Australian football was codified before soccer and rugby. Tom wanted to send the Melbourne and Geelong clubs to England to play exhibition matches, or one to England and one to America. The proposition was carried in Adelaide but lost in Melbourne.

Tom Wills stabbed himself in the heart in 1880 and was buried in an unmarked grave at Heidelberg. His mother said, “Thomas – I never had a son called Thomas”, and he was forgotten.

But back at Moyston, the grand home Horatio Wills built with hand-made bricks still stands. It’s built in a square with a hollow interior to assist with its defence in the event of attack. Down the hill to the east is an area of flat land with a small waterway running through it. The locals say this is where the Tjapwurrung played their football. For a boy who loved games, it must have been like seeing the circus come to town. A few ks to the south is the Moyston footy ground.

Moyston Football Club fell on hard times in the 1990s. Willaura Football Club, just down the road, hadn’t won a flag since the 1970s. To survive, they merged but that seemed not enough. One night, Moyston Willaura, otherwise known as the Pumas, had only five players at training. They approached the best player in the club’s history, Wild Dickenson. At 61, he made a comeback, playing when he had to. And a local farmer’s wife, Ruth Brain, was elected club president.

The Moyston Willaura footy club hung on for 2008, the AFL’s 150th, when surely their club would be the grass roots club that would bask in some of the glory of the Australian game and what it had become.

Instead they received an e-mail, delivered with the authority of the AFL, saying that the idea of the game having Aboriginal origins, while having sentimental appeal, was unfortunately not sustained by the latest research.

I am about to criticise someone, sports historian Gillian Hibbins, so I wish to say first what I respect in what she has done. With Anne Mancine, she edited a biography of Tom Wills’s cousin, HCA Harrison – a most valuable book. Hibbins’ area is the Melbourne Cricket Club during the 1850s which she writes about authoritatively. Nor does it bother me one whit that she doesn’t like Tom Wills. A lot of people didn’t like Tom Wills.

But a lot of people did. He was like Warnie. He divided opinion in part between those who played with him and those who played against him. And he’d play with anyone.

Hibbins sees him as being temperamental, immature and selfish. The reason we need to hear that is because it’s what Tom Wills’ critics said in his day – and he had plenty of critics in the Melbourne Cricket Club, particularly after Tommy got into a fist fight with a few of the members after they called him a cheat.

Two members of the MCC committee were also influential journalists of the day. Anyone basing their view of the history of the game on the writing of those individuals will not be hearing the case for Tom Wills. One of them, Wills’ predecessor as captain of Victoria, alleged Wills broke his arm with a short ball when he couldn’t get him out any other way.

In 2008, the AFL celebrated its 150th year. An official history was produced and given an eminent place in the book was an essay by Gillian Hibbins titled “A Seductive Myth” and sub-titled “Wills and the Aboriginal Game”. Basically, her argument boiled down to the assertion that as there was no evidence of Aboriginal football being played at Moyston, it could not be assumed that it had.

What is at issue here is the prize of who invented the game. For a long time it was assumed that Australian football was a colonial off-shoot of 19th century English school games. Clearly, it was heavily influenced by them, but that does not sever Tom Wills’ link with Aboriginal football.

Well here are three things I know about the debate as to whether Aboriginal football was played at Moyston. Number one – the local Aboriginal people, the Tjapwurrung, had their own word for football. Mingorm. Did the Italians invent the word macaroni without ever having seen or eaten a macaroni? Did any people in the history of the world ever invent a word for something which wasn’t there?

Number two – James Dawson was a Scottish squatter in the western district in the 1840s who actually liked Aboriginal people and spent a lot of time with them. His 1881 book Australian Aborigines. The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria, Australia … is one of Victoria’s treasures. Dawson describes a big coroboree at Terang where he gives an elaborate description of the Aboriginal football he saw being played, especially the leaping and kicking. Dawson lists the Tjapwurrung as being one of the tribes present.

This part of the argument was interpreted by Amy Saunders, a very smart Koori woman some of you may know from the band Tiddas, in the following terms: Do you know what they’re saying now? (By “they”, she means us, the whitefellers). “They’re saying there was a tribe of blackfellers in Victoria who didn’t like footy. Well, they must have all got killed out because there’s none of them around now”.

And, thirdly, the closest living person to the whole Tom Wills story is Lawton Wills Cooke, now into his 90s and here in Melbourne. He is the grandson of Tom Wills’s younger brother Horace. Horace told his daughter, Lawton’s mother, and she told Lawton that when Tom Wills was at Moyston he played Aboriginal football with a stuffed possum skin bound up in twine.

In 2008, I felt the Moyston Willaura Football and Netball Club had been done a grave injustice. And so, with its president, Ruth Brain, I took on the AFL. The first time I rang her she said, “Hang on, I’ll get a stick and write down your number in the dirt”. She was in a paddock. The second time I rang she was laying a netball court with Les, the old bloke from the next farm she ran to and from the footy each week.

Ruth was a boarder at Genazzano. She’d gone on to university but her heart was in the land so she’d gone home, got married a farmer and had four sons. She was red-haired and cheeky and brave. She knew the Tom Wills story as well as I did. She brought the footy club back to thriving health then became the first woman president of the Mininera and District Football League. I have heard it said she saved the indigenous game in the Mininera district. And, at 52, she died last year of heart failure.

Five days later, Moyston Willaura played for and won their first premiership. They fought for everything. On their hands and on their knees. My son-in-law came with me to the game. He is, like me, a Tasmanian of convict descent. A former coal-miner, he also has Aboriginal ancestry. Afterwards, when I asked him what he thought of the game, he said, “It was like she was there but wasn’t there”. You were aware of it from the moment you stepped into the ground. I have seen footy matches played to honour a spirit before but never for a woman and never as powerfully.

Ruth Brain’s vision was for Moyston to be to Australian football what Bowral is to Australian cricket. And my purpose in speaking to you here today is to commend that vision to you.