2 August 2015, Adelaide, Australia

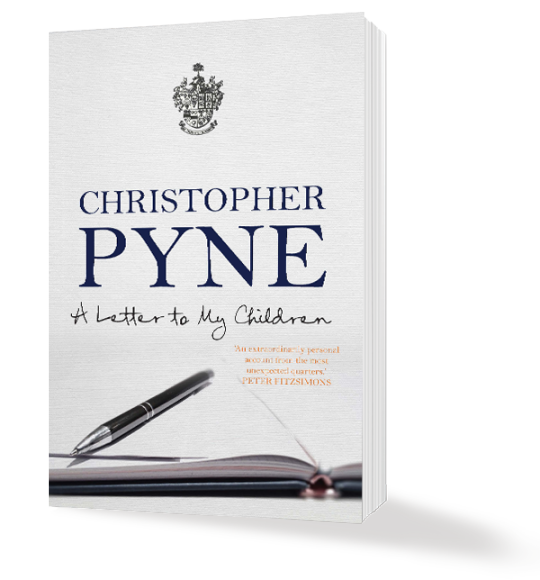

Annabel Crabb launched Christopher Pyne’s book, “A letter to my children” with her own letter to his children. Annabel letter was as follows:

We are all gathered here today because we have something in common. Either we love Christopher, or we are irreversibly related to him, or we are a little bit frightened of him. Or we are here for the sport. I won’t – being an irreproachable paragon of ABC independence – vouchsafe exactly where I am located on that spectrum, though I’m sure if you give it about 10 minutes Chris Kenny will write the definitive account.

I have known Christopher Pyne for many years. I knew him when he was no one. And the strange thing about Christopher is that even when he was a no one, he really did give the strongest possible impression of being a Someone. This peerless long-range optimism has paid off so richly that – a mere 25 years or so since I met him at the University of Adelaide, where he was a charmingly merciless campus Liberal trying to rebuild the Student’s Association in his own glorious image – he is now the charmingly merciless Federal Minister for Education, trying to rebuild the entire university sector in his own glorious image.

And now he has written a book. And – in one of the most rewarding tactical blunders of his political career – he has given me what I understand is a speaking slot of unlimited duration to hold forth on the subject of it and him tonight.

This book is audacious – let us not pretend otherwise. It was written during a truly punishing year as Education Minister, during which its author additionally foxtrotted with characteristic nimbleness through what must have been a rather delicate period of party leadership tension in February and March. Christopher – I should in fairness point out – insists that he wrote the book during his holidays, and while on planes, and helicopters, and on his way to Sophie Mirabella’s wedding, and so on.

The book itself is part Profiles In Courage, part Nancy Mitford and part Dreams Of My Father. In the modern Liberal Party, surely Christopher Pyne is the only person who could cheerfully borrow from two American Democratic presidents – one dead, one Kenyan – and live to tell the tale. I can only assume that George Brandis’s new arts funding organisation is hastening plans to finance the book’s inevitable production as a musical, and that is something I deeply commend. Efforts will need to be made, of course, to dissuade the Education Minister from playing himself.

In fact, I commend this book to you on many counts. I commend to you page 65, which has a very entertaining account of the young Christopher’s pivotal charming of local matriarch Lorna Luff in his quest for preselection in the seat of Sturt. I commend to you page 197, which gives us the long-awaited blow by blow account of what was said that night in 1995 between Christopher and the aspiring triple-bypass recipient John Howard – a conversation that of course, sadly, bought our hero a decade on the back bench. I also commend to you the book’s first chapter, which is a moving, honest, and insightful account of Remington Pyne’s death, and that event’s effect on his younger son.

I have known Christopher for a long time and had always assumed that his personal characteristics were – like Sleeping Beauty’s – the result of inconsistent degrees of attendance from good and bad witches at his christening. But when I read that chapter, in all seriousness, I understood a lot more about the man and the public figure that Christopher is – his urgency and his steeliness, and his utter indefatigability. Over the course of the rest of the book, with its sporadic and entertaining tales of growing up in a family where Christopher was reputed to be the shy one, I learned where his matchless sense of humour and fun comes from.

The life and exploits of Remington Pyne and a joy and inspiration to read, and I think it is a great public good to have them so lovingly recorded.

I do have one niggling concern. I would never suggest, of course, that Christopher M. Pyne is ever driven by ulterior motives, either in his political or private lives. But this letter to his children seems terribly convenient. A 240-page paean from a well-behaved, successful and industrious child to a Godlike, charming, respected father? Just what is Christopher trying to say to his children? Do I detect some subliminal expectation that the book’s addressees will respond – at some point, preferably as their matriculation project – with an answering published work of adulation for their own father? A heroic sculpture, perhaps, for North Terrace? Moving and informative as this book is, is it possible that it is also the most outrageous passive-aggressive parenting manoeuvre ever?

With that possibility in mind, I resolved that I would launch this book by reading aloud my own letter to Christopher’s children.

Dear Eleanor, Barnaby, Felix and Aurelia,

Don’t worry. I’ve read your father’s book, so you don’t have to. I am happy – in my responsible journalistic way – to summarise and provide you with the York notes. But I’m also going to pop in a few things Dad left out when itemising the key values indispensable to a successful life of public service.

Patience, courage, determination – yes, yes yes. You’ll need all those, fine. But there are other important principles you can learn from your father.

First: When Circumstances Change, Change Your Mind.

When I approached your Dad a few years back to be one of the guinea pigs for a new series called Kitchen Cabinet, he was at first hugely enthusiastic. We agreed that he would cook with Amanda Vanstone in her kitchen. We discussed serving Roquefort, as Roquefort is a cheese only available in Australia due to an especially commanding executive decision announced by your father on the 23rd of September 2005, when he was feeling his oats as the Parliamentary Secretary for Health, John Howard having cracked the freezer door slightly open. (That’s another tip, children: Always say ‘Yes’ to cheese.)

But as the filming date drew nearer, his mood grew darker and darker. ‘I’m not doing it,’ he’d ring up and wail. ‘It’s going to be a disaster. Amanda and I are going to be sitting there eating expensive cheese and drinking wine and looking like elites. Plus, she’ll tease me. Australians aren’t ready for a politician who talks with his hands. I’m not doing it!’

Children: On the day, I was obliged to be brutal. I told him he had no option of pulling out, and that the ABC had already flown four camera crew to Adelaide. And we know how strongly your father feels about prudence with ABC production resources in Adelaide. I got Mark Textor to call him pretending he had focus group polling suggesting that his participation would resonate particularly well in Klemzig. He turned up. We cooked lunch. All of your father’s worst fears were realised. As he left – to collect you from piano practice, Eleanor, I believe – I said to him ‘See – that wasn’t too bad, was it, Christopher?’ Through a frozen smile, he muttered: ‘Career-ending.’

Later, when the episode went to air, it spawned an unprecedented national wave of Pyne-love, first encountered by your father the morning after the broadcast, when someone approached him at, I believe, Hobart airport and declared: ‘You know, you’re not as much of a knob as I thought you were!’

I had a phone call soon after from your ebullient father, convinced that the show was the best idea he’d ever had. So remember, children: A bad idea is only a bad idea until it turns out to be a good idea.

Point Two: Negotiation.

I would have written more about this, but I know you are across it already. I’ve heard the stories about you four. When Christopher declared that he would move out if you children got one more pet, you bought a rabbit immediately. That’s smart. Always bluff in these situations. It’s what he’d do. And has he moved out? No. He hasn’t. Lesson learned. In short, kids: You’ve fixed it. That’s because you’re fixers. Good work.

Point Three: Loyalty.

Now this is an important one, tiny Pynies. Loyalty enhances the giver and the receiver. And loyalty is a significant part of your father’s credo in federal politics. Fifteen years or so into his political career, your father learned an additional, valuable lesson about loyalty: It works even better if you’re loyal to the actual person in charge, rather than the person you hope will one day be in charge. He’s never looked back, and neither will you.

Now, my dear little Pyne saplings – don’t worry. I’m not going to lecture you for page upon page upon page. I know perfectly well that you can get that at home.

But I want to mention two more things. The first is an unshakeable and central tenet in public life that is well recognised by your father, and acknowledged in his book, but nevertheless bears repetition.

And that is: Marry well. Your grandfather did, in the spectacular Margaret, as the book makes very clear. And so did your father. Really, that can make all the difference. And for the heavy price you pay, the four of you, for your father’s lifelong contribution to public service – the constant absences, the embarrassing Internet memes, photo shoots in The Australian, the inconvenience of studying in an education system over which your father has nominal control, the alarming ‘win at any price’ approach he adopts to games of ‘May I?’ or Monopoly – always remember, he made at least one truly brilliant decision in his life – to marry Carolyn, of whose wit, originality, decency and great good sense you will always be the beneficiaries.

The second is that – and I don’t mean to ease up on teasing your father for very long, because Lord knows there is no one on this good Earth who is more fun to tease than Christopher Pyne – there is a grandeur to public service, and he is right about that. Not grandeur in the ‘having your own helicopter’ sense. Grandeur in the untold possibilities of public service, where an inquiring mind and a stout heart can make anything possible, can change any injustice or idiocy or root out any corruption or stop any wastage of public resources. Grandeur in the sense of having a series of beliefs and having the courage and the intrepidity to prosecute them at lengths, and persist even when things are hard, rather than just reclining with a beverage to whine about the situation. (That, children, is the job of journalists, in case you were wondering).

So never cease to feel proud of your father for that, and for the fact that he brought Roquefort to Australia, and for the fact that he, and his father before him, worked hard and were adventurous and outrageous and not very good with pets and always had the capacity to laugh. Remember that your father – in an age where politics has become about caution and covering your behind and striving to say nothing at all that is memorable – has become not only one of the most powerful politicians of his time, but also one of the great characters. That’s not an easy thing to do nor is it an easy life to lead. It’s what I most admire in him.

Also remember that for all that you might have missed your father over the long years when he was absent for weeks at a time – imagine how much worse it would have been to have him at home.

Yours sincerely,

Annabel Crabb

Purchase book here.