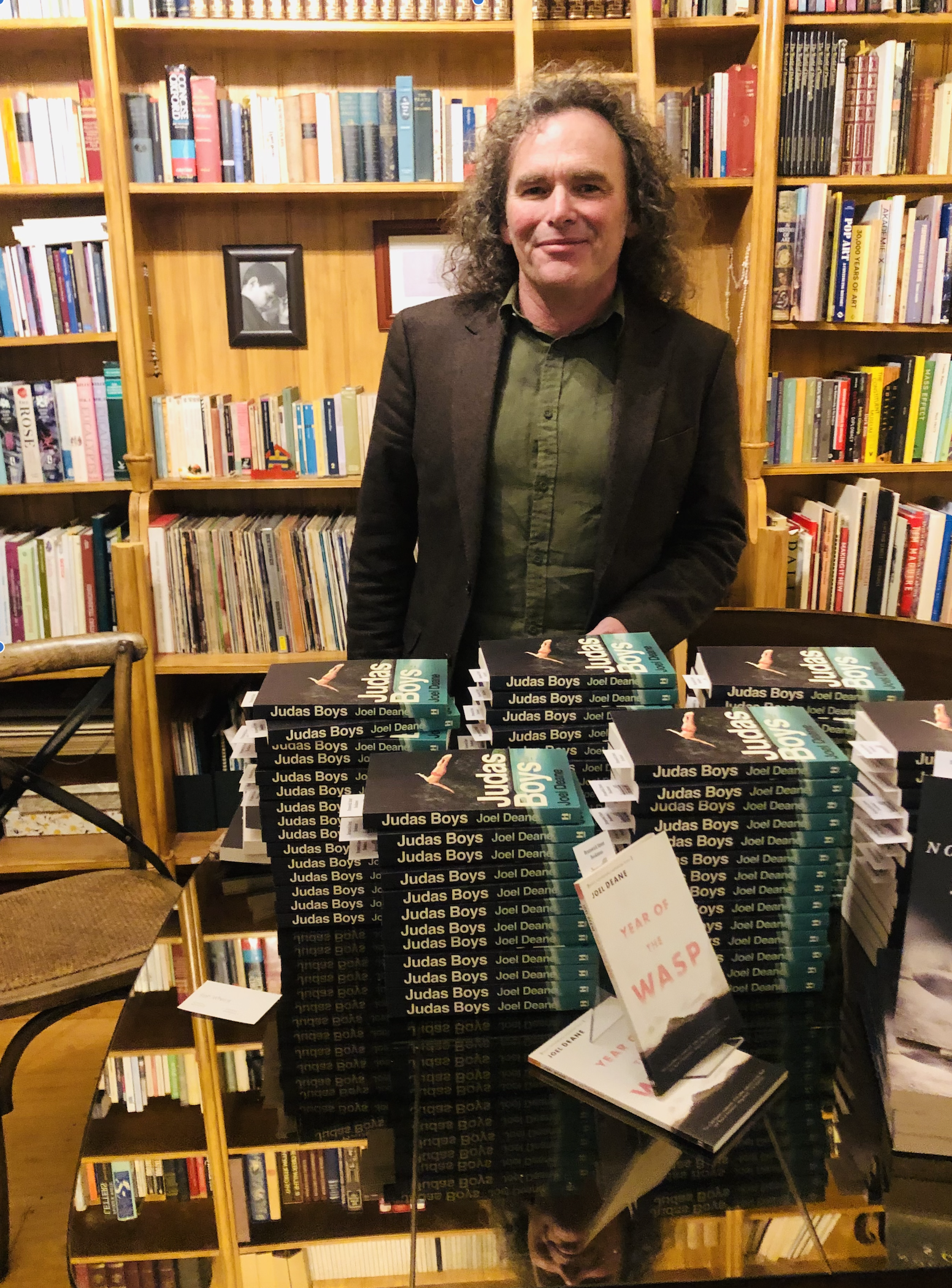

8 August 2023, Collingwood House, Melbourne, Australia

Last October Joel Deane published a poem on his blog -- intriguingly titled, Things I wish my father taught me. I’m going to read it to you.

Yesterday is

ash. Tomorrow is

smoke. Today is fire.

I don’t know what provoked Joel to write this fine little poem, but it’s hard not to think about the Black Saturdays of our recent past, and the fires that probably lie in our future.

Read that way it’s a grim, even apocalyptic, poem. But it can be read in another way.

Everything behind us has been reduced to embers, and the future can’t be seen – so don’t dwell too much on either of them.

What we have – the only thing we have -- is the fire of today. The spark, the light, the warmth that keep us alive.

Fire is death and fire is life; the potential instrument of humanity’s end, and of its beginning.

Everything in the poem turns on the two-faced nature of fire.

Joel knows better than most that good poems are in some ways allusive and elusive.

Their meanings – even the meanings of individual words within them – are often not clear.

The reader has to do the work.

And as we do the work, our imagination expands to fill the space the poet has left for us, and we find meanings in the poem that even the poet might not have intended.

But, of course, while Joel is first of all a poet, he’s not only a poet.

He has written three novels, and he wrote Catch and Kill, a superb account of the Bracks and Brumby Governments.

And, famously, he worked as a speechwriter for both those Premiers.

So a question that fascinates me: how does a poet become a political speechwriter?

How did Joel make the journey from the ambiguity of poetry to the brutal, cut-through clarity demanded by political speech?

How, and why, did he leave the Shire of poetry, where language is life itself, and enter the Mordor of politics, where lovely words go to die.

When I was a speechwriter, I learnt that trying to guide your elegantly crafted lines through eight or 10 speech drafts while an army of public servants, advisers and media people pore over it is like trying to walk a baby gazelle across an eight-lane freeway at rush hour.

When Joel was appointed Steve Bracks’ speechwriter, The Age wrote an article about him and published one of his poems.

The Attorney-General Rob Hulls rang him up and said, “Your poetry’s shit, mate. It doesn’t rhyme.”

To which Joel replied, “Rob’s more of a dirty limerick man.”

But all frustrations aside, drafting speeches was one of the best things I’ve done as a writer, and I’m sure that was true for Joel as well.

In trying to capture the thought and voice of another person, you have to put away your ego. You sometimes have to express ideas you don’t agree with.

You have to understand, as Joel once wrote, that “Australian politics is suburban – it’s not the West Wing, it’s the sausage sizzle at Bunnings.”

I never had the pleasure of working with Joel but I have no doubt he was a good speechwriter.

He was in the job for the right reasons. He believed in the people he worked for and in the larger social democratic ideal that they embodied.

In a time of huge cynicism about political language, Joel still believes, as he once said, that rhetoric is a good thing in the hands of good people.

Still, the solitary writer in him couldn’t resist small rebellions, pebbles thrown under the chariot of power.

In 2005, he inserted the phrase, ‘constitutional conflagration,’ into one of Steve’s speeches, and somehow the advisers missed it.

It’s an iron rule of speechwriting: never insert anything that your boss might trip up on.

According to a book on White House speechwriters I read, one of them once put ‘indomitable’ into a presidential speech, and was told to take it out.

He replaced it with ‘indefatigable’ – and was sacked on the spot. His replacement put in ‘steadfast’.

Joel escaped the sack but he remembers watching his then chief of staff, Tim Pallas, making a bee line for him in the office after the speech.

Pallas said, very gently: “Mate, just wanted you to know that the Premier gave ‘conflagration’ a red-hot go.”

A few years later Joel had to write a speech for Pallas. He threw in a ‘conflagration’. Pallas did not give it a red-hot go.

Joel has dedicated Judas Boys to Michael Gurr – a close friend of his, and of mine, who died in 2017.

Joel and Michael wrote speeches together for Steve Bracks.

I feel envious not to have sat in on their conversations, as they riffed off each other.

Michael once wrote that writing speeches for state politics meant “dreaming of the Gettysburg Address and waking up to the Cheltenham Chamber of Commerce.”

But when he spoke at Michael’s memorial service, Steve Bracks said that when you delivered a speech written by Michael to the Cheltenham Chamber of Commerce, it always felt a bit like you were giving the Gettysburg Address.

I’m sure he would say the same about Joel.

As a former journalist, public servant, and press secretary, Joel was shaped by the newsroom, the bureaucracy and the political office.

He became a master of many voices – as the journalist Ken Haley wrote when he reviewed Catch and Kill, “Deane is several writers rather than one.”

All these cultures and languages Joel has lived in, all this poetry and politics, have shaped the writing of his new novel.

Joel began working on Judas Boys in 2017, soon after the deaths not only of Michael Gurr but of his father, Barry.

Both deaths were untimely and shocking, and left much bewilderment and sorrow in their wake.

Over the years, Joel had kept in touch with some of his old Catholic school mates, first at the Marist Brothers in Shepparton, then at St Kevin’s in Melbourne.

A few of these boys had suffered the abuse that we now know a lot about but that had been hushed up for decades.

Joel also dedicates his book to those boys “who lost their way and never made it back.”

With these awful events in his head, with an intense but entirely unfocussed feeling of anger, Joel began to write.

His labor in the salt mines of writing took six years and 25 drafts. It nearly killed him.

But I’m here to say that Joel’s pain is our gain.

Judas Boys is a gripping read, with strong characters, a total page turner.

I don’t want to say too much about the story. It’s an unfolding mystery, a roman a clef, as the French say. I want you to read it and turn that key for yourselves.

But I’ll say a few things.

Judas Boys is in no sense a hidden memoir, yet the writer has drawn on some crucial life experiences. They include a Catholic boyhood and education, and his moment as a small, frenetically whirring cog in the political machine.

His narrator, Pin -- short for his surname, Pinnock -- works for Benedict Cox, a Labor MP who wants to be Prime Minister but is having to do his time as Assistant Minister for Regional Tourism.

Now, Coxy is a piece of work. If you’ve spent any time around a political office, you’ll know the type.

Joel describes him like this:

“Cox is a trophy hunter. Everything he thinks, says, does, is geared to winning the silverware. He’s never told me what prize he’s after. He doesn’t have to. Some trophy hunters just want a seat in parliament, others want to be a minister, but they’re just making up the numbers. The thoroughbreds, the egomaniacs, dream big. They want to be prime minister, want it so much they fire themselves like a human cannonball at the world in the hope that the arc of their ambition falls in sync with the vagaries of the political gods. Cox is a thoroughbred.”

In this portrait I see Coxy so vividly. I reckon he wears a single-fronted navy-blue suit with a white shirt, very pointy black shoes, and spends a lot of time checking his phone.

He calls people ‘Comrade’, though he’s about as communist as Twiggy Forrest.

Many years earlier, Cox and Pin had boarded together at St Jude’s, the upmarket Catholic school that gives the book its name, Judas Boys.

The book ping-pongs between two time periods, between Pin’s dysfunctional years as a political operative and his dark years at St Jude’s.

At the school Pin’s main friend – if that’s the right word for such a sad, damaged relationship – is David O’Brien, known to everyone as OB.

I feel like I remember boys like OB – boys whose surface exuberance hides some deep sorrow.

Boys who we know really need our friendship but who are also so annoying they drive us away, leaving us with deep guilt that in the end we were not large enough to protect them.

Judas Boys is brilliant on the brightness, mystery, terror and cruelty of adolescence – at times it reminded me of Lord of the Flies.

Joel shows how feelings for a band, in this case Lloyd Cole and the Commotions, can capture the intense urges and no words of teenage male love.

Or listen to this. Pin, now an adult, has just walked on stage to give a talk at the school he once attended:

“At first I don’t see the boys - just feel the impatience of so many young bodies harnessed, tied, and buttoned into matching uniforms.” That’s good writing.

Or the portrait of OB’s Dad, Tom. He is a classic absent father. He calls his son ‘sport’. Anyone raised in Australian masculinity knows that’s a problem.

Tom’s marriage to Mrs O’Brien – who is the object of Pin’s desire – is not good, to put it mildly. Joel manages to convey this in one brushstroke:

Pin, the narrator, is hiding in OB’s bedroom: “:I listened as Mr O’Brien banged about in the kitchen – he didn’t seem to know where anything was…”

But what we gradually learn – Joel is good at allowing the mist to come very slowly off the mountain he has created – is that the life of the father has been blighted by the same power that destroyed his son.

As OB will say: the spark that was stolen from me was also stolen from him.

The villain here is revealed so fleetingly that you might miss him, like the killer in the Antonioni movie Blow Up, seen for just a second as the pictures develop in the dark room.

But Joel catches him in another vivid brushstroke:

“His silver hair was slicked back, his green eyes cold, and his oversized head the shade of supermarket ham.”

Judas Boys is about the passing on of trauma -- through institutions and through families.

No doubt it has a bleak worldview. The writer understands how hard it is to shake oneself free of pain incurred early and ingrained very deep.

Yet the book’s final scene – to which Joel brings all his poetic gifts – evokes, with no sentimentality, a faint, fragile and haunting possibility of redemption.

Joel, as I read Judas Boys, I wondered whether it marks a new direction for you.

Whether you have more to explore about all the cultures that formed you, and that have shaped your words.

And whether that exploration might take the form of poetry, memoir or more fiction.

And though you have already a fine body of work behind you, I am sure that the best lies ahead.

And so it gives me great pleasure to launch Judas Boys.

I urge you all to read it and to spread the word about it.

Let’s celebrate the fire that enables and drives Joel Deane to write, and trust that it will burn for a long time to come.