9 May 2008, North Fitzroy Arms, Melbourne, Australia

In his 1899 Reminiscences of the Ballarat Goldfield, J. Graham Smith tells the story of Algyron Ratcliff, the ill-fated second son of Irish nobility. Algyron fell in love with and secretly married Mathilde Rolleston, the daughter of a Protestant minister. Algyron was promptly disowned, and like many a second son, immigrated to the gold fields of Victoria with his new bride and her sister Gwendoline. At Ballarat, ‘Algy’ couldn’t find a digging mate to suit his patrician standards, so ‘Gwenny’ volunteered to become a miner. At first Algy refused her outrageous offer, but they soon ratified their new partnership over a cup of tea. Gwenny worked the windlass and went down the mine shaft, while Algy, who was of delicate health, kept his feet above the ground. Gwenny wore men’s clothing to disguise her identity; not, as she tells it, because she was ashamed of her new calling, but for the sake of her brother-in-law, whose manliness might be called into question by fellow miners.

“In one way I liked it”, she told her chronicler Graham Smith. “There is a subtle fascination in searching for the precious metal. I was not frightened to come in contact with the diggers, as I was of being overhauled by the licence hunters.”

Gwenny boasted to her sister Mathilde of her new-found skills and talents. “See what an amount of knowledge my digging apprenticeship has given me. I can talk of alluvial stratas, of sandstone, pipe-clay, and slate bottoms, of alluvial and quartz deposits.”

“My dear Gwenny”, interrupted Mrs Ratcliff, who kept house for her husband and subversive sister, “I believe you will be less contented and joyous when you resume your proper situation in the old country than you have been in Australia with all its discomforts”.

This alternative women’s liberation narrative — the story of freedoms found by women on the gold rush frontier — is repeated by Harriet, another cross-dressing Irish girl who accompanied her brother to the diggings in 1854, the year of the Eureka uprising. Harriet was performing a quiet rebellion of her own. “I purchased a broad felt hat, a sort of tunic or smock of coarse blue cloth, trousers to conform, boots of a miner, and thus parting with my sex for a season (I hoped a better one), behold me an accomplished candidate for mining operations, and all the perils and inconveniences they might be supposed to bring”. Writing home to Ireland she confided, “Wild the life is, certainly, but full of excitement and hope; and, strange as it is, I almost fear to tell you, that I do not wish it to end”. Could Harriet’s season of transgression possibly be made to last a lifetime?

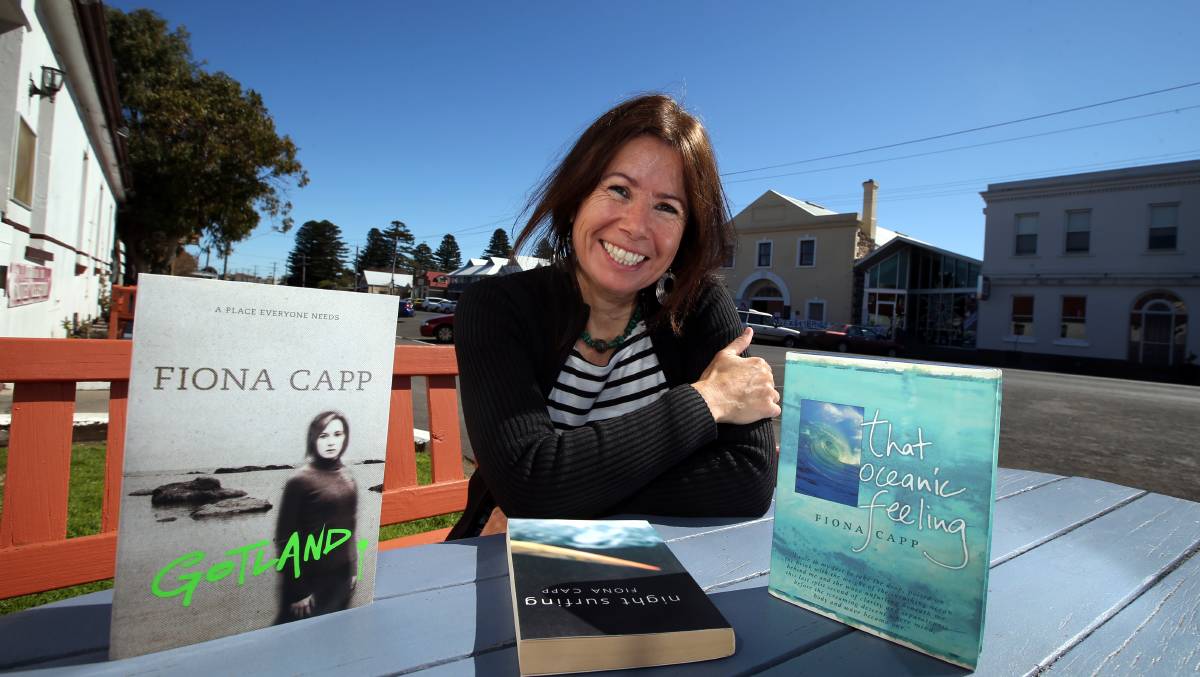

These are the words of Mathilde, Gwendoline and Harriet, culled from the archives of mid-nineteenth century Victoria. But they could be the voice of Jemma Musk, the heroine in Fiona Capp’s new novel, Musk and Byrne, which I have the great pleasure of launching here tonight. I couldn’t help but recall these tales of feminine transmutation and defiance of the gender order, hewn from my own current research into the role of women at the Eureka Stockade, when reading Fiona’s wonderful book. Both tell tales of outlaws, those who live without society’s moral and ideological sanction. There is, of course, one major difference. As an historian, I trade in the factual. As a novelist, Fiona has wrought a magnificent fiction.

I know that in inviting me to launch her book, Fiona has been extremely anxious about the accuracy of the historical detail she employs to craft the story of the artist Jemma, her hard-working Swiss immigrant husband Gotardo, and the dashing, seductive geologist Nathanial Byrne. It strikes me that it takes a lot of courage to write historical fiction in the post-Secret River era. Perhaps Fiona was worried I would take Inga-esque exception to her method or her conclusions.

In her widely read 2006 Quarterly Essay, “The History Question: Who Owns the Past?”, Inga Clendinnen lined up historians and novelists on opposite sides of a gaping chasmthat she calls ‘the moral contract’. Novelists, she tells us, are at liberty to ‘kick loose, inventing things which might have happened but we don’t know did, because they are the kind of things that records always miss’. Novelists, Clendinnen argues, ‘enjoy their space for invention because their only binding contract is with their readers, and that is ultimately not to instruct or to reform, but to delight’. Historians, on the other hand, must endure ‘the burden of dealing with the real’. Clendinnen disclosed — in the most public of forums — that the novelist’s ‘practiced slither between “this is a serious work of history” and “judge me only on my literary art” has always annoyed me’. Kate Grenville obviously copped the rough end of Inga’s exasperation.

I am very pleased, for Fiona’s sake and for my own, to be able to say that Musk and Byrne did not, in any way, irritate, aggravate, infuriate, denigrate or humiliate my historian’s sensibility. To my mind, Fiona has upheld the moral contract to her readers to delight and captivate, while also holding true to the spirit of the times and the people she has so meticulously portrayed. To answer your doubts, Fiona, I don’t honestly know whether all the details are correct. In fact, your insecurity proved infectious. Reading the book, I got to worrying about my grasp of the historical minutiae. Did goldfields’ buildings have bluestone foundations in 1868? Were the streets macadamised? Did babies sleep in cots big enough to fit a curled-up man? I really don’t know. And — may Inga be my judge — I don’t much care. To my mind, this book gets it right.

And this is why. I believed in Jemma Musk. I believed in Jemma Musk in a way that, I must admit, I did not believe in Kate Grenville’s William Thornton, whose inner life was invested with too much of a contemporary sensibility for my comfort. Nor did I believe so thoroughly in Lucy Strange, the heroine in Gail Jones’s acclaimed Sixty Lights, who, like Jemma Musk, is a woman at odds with her era, pushing the boundaries of conventional wisdoms and orthodoxies. Yet, for me, Lucy Strange never quite inhabited her temporal landscape in a way that was convincing to someone who has spent over a decade investigating the lives of women — especially challenging, nonconformist women — in the nineteenth century.

But Jemma Musk is a fully embodied character, largely because — and I know this doesn’t sound very academic — largely because Fiona has given her a subjectivity that feels right. In Musk and Byrne, Fiona takes her readers deep into the emotional landscape of her historical protagonists. Apart from the beautiful writing and gripping plot, this is the aspect of the book that most stirred my imagination — historical and modern. These are the details that I feasted upon, the very ‘kind of things that records always miss’.

How did women experience the loss of a child? Just because it was as common as mud, did they grieve the loss any less bitterly than women in our medically advanced times? To what ends did their suffering drive them? And how did women who were not content to keep within the circumscribed borders of a settled domestic life create an identity that was outside the fold? How did it feel to know that neighbours, employers, husbands could daily occupy subterranean spaces yet could not fathom the mysterious depths of a woman’s heart? At what price freedom?

These, to me, are the sort of historical questions that have no concrete, empirical answer. This is the unmistakable terrain of the novelist. There is a pivotal scene in the book where the earth suddenly collapses under Jemma and Gotardo’s property, rupturing along invisible fault lines created by the honeycomb of mining tunnels that run under their land.

Jemma is at the kitchen trough washing the dishes and looking out over the yard while Gotardo drives the bullock dray over the soil of the vegetable patch in preparation for planting. The bullock plods backwards and forwards across her field of vision and she barely registers its presence until Gotardo suddenly cries out and lurches drunkenly from his seat. He is still holding the reins as the bullock dives headlong into the earth, as if summoned by a call from the underworld, the dray following the bullock’s descent into the gaping ground. As the cave-in tears across the field like a sizzling fuse, Gotardo manages to jump clear of the dray just in time, his fall cushioned by the freshly turned earth. When Jemma reaches her husband, he is on his knees staring with disbelief at the deep cavity into which his bullock and dray have plunged. (111)

It’s an arresting image, I think, and one that becomes a thematic signpost for other human and fateful betrayals to follow, where all that’s solid melts into air, where seismic shifts can happen in an instant and one is left to contend with the rubble of existence. This book is not so much about centres and margins — as you might expect in a tale of outlaws and immigrants. Rather, it’s all about layers and surfaces, external appearances and interior realities.

But in the hands of a novelist so technically capable, so historically empathetic and so psychologically attuned as Fiona, you can trust that in Musk and Byrne we are taken on an exhilarating ride across a literary topography that is mercifully free of chasms, rifts and other insufferable holes. Despite Fiona’s recent article in the Age, where she espoused the need to re-position women symbolically in outlaw mythologies, there are no hidden agendas in this book. It’s not a period piece disguising a progressive plot. It’s neither contrived nor disingenuous. Again, this is why I believed in Jemma Musk.

There is one more passage I’d like to read, perhaps my favourite in the book. Jemma has abandoned her home and family. She’s changed her identity, not by donning male clothing, but, conversely, by playing the role of a dutiful wife and devoted maternal figure. It is during the night that Jemma’s own emotional ruptures appear, groaning under the tension between her inner and her outer life. Jemma and Nathanial are making love.

And now without warning, without even a word, she turns to him and suddenly ignites. As soon as he touches her, she is molten, imploring him to go on. There are no rules for this kind of lovemaking; them must make them up as they go. He has the sensation of them falling into darkness, into a vast space without gravity … Jemma tears at his shoulders with her fingernails, fighting him off and drawing him close, wrestling to fill the emptiness that can’t be filled. She claws and bites him, as if inciting him to return the pain. It is clear to him what she is seeking. Annihilation. For nothing else to exist. To be consumed by the fire of their bodies … And so they toil through the night until Jemma finds the oblivion she seeks. (224)

Whether Mathilde, Gwendoline or Harriet ever experienced such agony and ecstasy I will never know. On the surface, these real women and the fictional Jemma Musk share much in common, conjoined by their defiance of expected roles and pathways, their transgressive acts and their pleasure in the wild possibilities of frontier living. But I have Fiona to thank for leaving me with the remarkable impression of what it might really have been like to be a woman on the edge.

It is with great admiration and respect that I declare Musk and Byrne officially launched.