16 February 2018, MCG, Jolimont, Melbourne, Australia

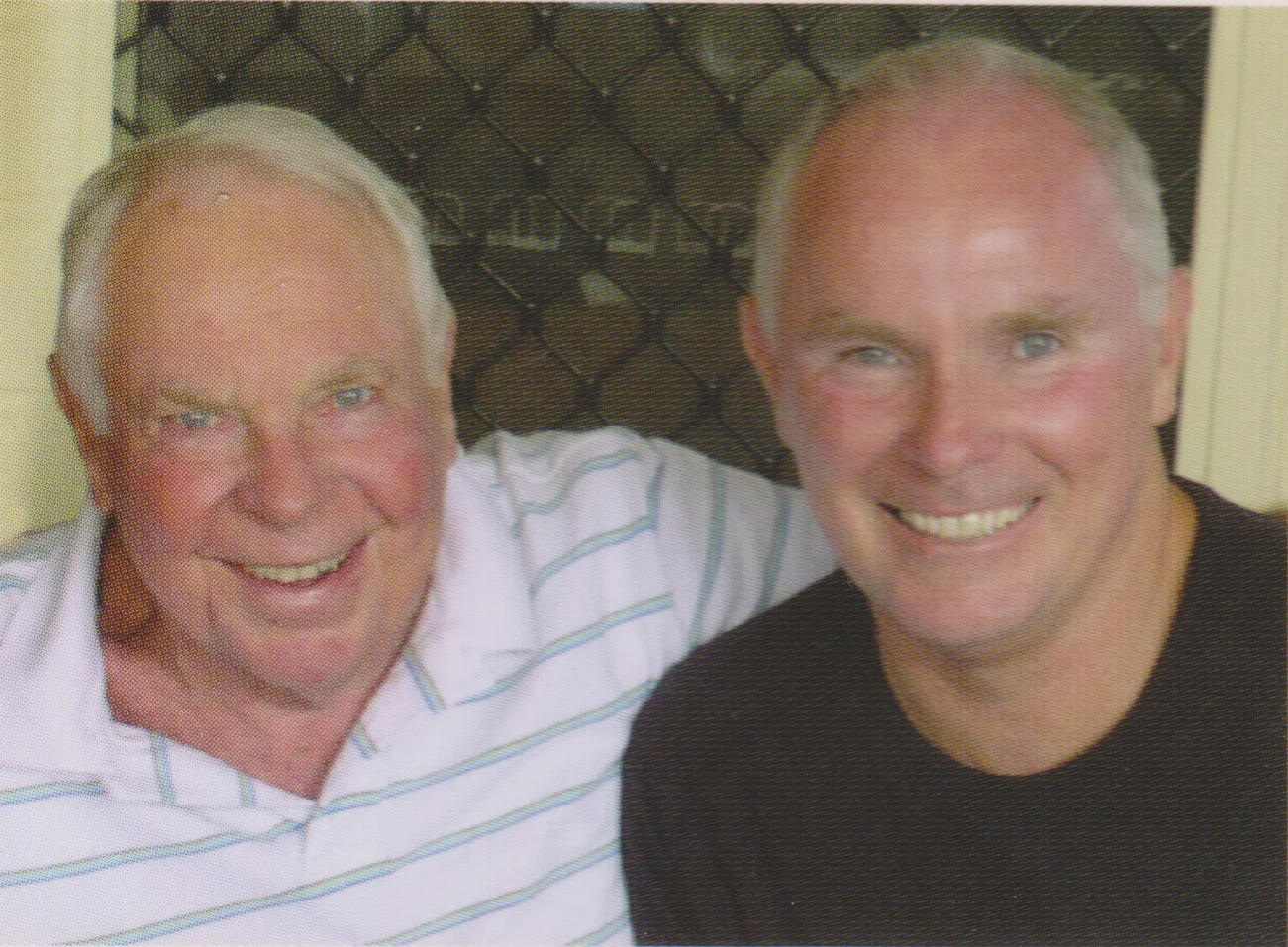

Well, we're here to celebrate Michael's life and to mourn his passing, to pay tribute to his life's work, to regret his voice having been stilled. We're also here to share the grief and pass on our condolences to Robin and to his son and daughter, Scott and Sarah.

In a place of many pillars, Michael was a defining column in the cathedral of Australian journalism and opinion. He journalism was marked by its integrity and consistency, a point Jim has already referred to. Perpetually characterised by his own lack of self importance, his determination not to inject himself into his stories, the ability to stand back and talk.

He possessed journalism's most fundamental attribute — to dispassionately assemble facts, to present them in a digestible and intelligent way, to give the reader the credit of understanding their import, to allow the reader the opportunity to come to a conclusion without the story needing colouring.

Michael's journalism carried that quality of understatement, which over time engenders regard in a reader appreciative of fact and insight, particularly in the age of self-expression where bellicosity is too often the hallmark. it takes a strong presence of mind and sense of self to remain unharried, to remain both focused and content with one’s judgements. Michael's line was always marked by that focus and conscientiousness of purpose.

Long careers in journalism and the judgments which attend them are part of the skeins which form the fabric of the country and society. And the loss of any one, an important one, carries a loss to us all. This is why Michael's passing transcends even the primal loss carried by his family and friends.

He was always fascinated by ideas and as his career was fundamentally in political journalism, he was fascinated by political ideas. In my case, this brought him to extend his journalism to a book, which Jim has already mentioned, ‘A Question of Leadership’, which he had published in 1993. This was built around what journalists have since labelled my Plácido Domingo speech, the December 1990 addressed to the National Press Club, perhaps, not perhaps certainly my one and only unguarded speech to the gallery. And the cause of my unguardedness was the death of the secretary to the treasury the previous evening, who had returned from Melbourne to Canberra to participate in an athletics event, only to die tragically coming off the field. In the reflection and sombreness of it, the following night, I was not of a mind to offer an entertaining political speech when someone of such substance, conscientiousness and commitment had been taken from us.

So I focused on the topic of why we were all there. What would we doing there? What was the essence of our mission? What was our duty to public life? And what was the appropriate role of journalists in the political side show? And in the speech I spoke of participants and voyeurs — whether journalists wish to be part of an integral integral to the national project, or whether they wish to sit on the fence and remain voyeurs, to report the high points but too often in the context of sensationalism. Or were they going to be in it for the policy ride and share the uplift, the psychic income or then to be diverted by the then opposition’s alternatives?

I argued what was central to national progress was leadership. That politicians as a class change the world, and that good ones make it very much better.

That is providing they have support on the big upshifts —when we move the whole structure up. I was trying at the time to convey the righteousness of the project and the constructive role journalists had already played in the big reforms to that time, and to not now fall for what was then the Thatcherite agenda of the then opposition.

Well, this whole notion of leadership and the role of leaders and the co-option of the media in the project really got Michael's attention. Mainly for the reason he was already a committed participant, as both Jim and Robyn's remarks make clear, the patriot in him always willed him to the high road agenda. In reality, he could not resist it. The speech got me into great trouble, of course, because of my focus on leadership, where I had said that Australia had never had leadership of the kind that had been provided in the United States at critical by Washington Lincoln and Roosevelt. As it turned out, this caused certain offense in some quarters <laugh> that the United States had a deeper sense of itself than we had, and that it had snatched its independence had written a constitution to guarantee and protect it.

Nevertheless, Michael saw the Plácido Domingo speech as me laying out the contours of an even larger canvas than the reformation of the economy. And hence his book ‘A Question of Leadership’ was written to alert people to that possibility, to that likelihood. So when I became prime minister, it was no surprise to him that having given the country a new economic engine, I wanted to reorient Australia towards Asia, attempt a true reconciliation with the indigenes and embrace a Republic — to let the country discover its blood energy, to let us know who we are and what we are, to give us the power to head full steam into the fastest growing part of the world but with our heads held high.

Michael loved the whole set of ideas, from Mabo to native title, the throw to Asia and of course the Republic. He would occasionally opine what a terrible loss the shift to a Republic had been in later life in conversations I had with him, and agreed that Australia could never be a great country whileever it borrowed the monarch of another country. He understood that there are no queen bees in the human hive, and as Jefferson has said, a monarchy was, of its essence, a tyranny,

Michael believed in an enlightened cosmopolitan Australia, one at a point of justice with its indigenes, open to the world, and ready to embrace its vast neighbourhood. Like the rest of us, he had to end endure the provincialism and the halting progress, but he never stopped believing in the larger schematic.

We will truly miss him.