28 April 2017, Ivy Ballroom, Sydney, Australia

The Press Freedom Dinner is a joint initiative of the Walkley Foundation and the MEAA. This speech first appeared in the Walkley magazine.

I was asked to speak tonight about political reporting in the era of “fake news”. It seems to be the issue dominating media industry discussion around the world over the past 12 months, but I’ve got a slightly different take in the Australian context as to what sort of threat it poses.

A good starting point is trying to work out what fake news actually is.

Everyone seems to have a THEORY.

So let’s begin with a bit of a pop quiz.

Is this fake news?

Well plainly yes it is fake news. There was a bunch of these stories that took off during last year’s Presidential election. It’s impossible to know how many of those who read them actually believed them or just read them for a bit of fun. But we do know the top 20 of these fake news stories generated nearly 9 million shares on Facebook. That’s more than the top 20 real news stories generated. So perhaps it tells us a bit about what Facebook users like. This one about the Pope endorsing Trump was the most shared. This is fake news.

What about this one?

Well yes this is clearly fake news too. This was number two on the most shared list. You can understand why people click on it and share it; it’s a far sexier story than “Hillary confirms education policy” or “Hillary talks tax”.

We now know much of this stuff was created by fraudsters in Macedonia. Or “entrepreneurs”, depending on your point of view. Facebook and Google are now taking steps to tackle this stuff with greater fact-checking and weeding out of obviously fake material, as they should. But I don’t really want to spend tonight talking about what they should and shouldn’t be doing. I freely admit to not being much of an expert on how Facebook algorithms work. I do understand this can be a balancing act at times. No one wants to see some of the brilliant satirical pieces from the Betoota Advocate blocked for example. Well, perhaps some of those radio & TV producers who didn’t realise The Betoota stories were satirical do …

But coming back to the stuff that really is fake news, here’s the thing: I actually don’t believe it’s much of an issue in Australia. I don’t see this as a great threat to our industry. In fact I haven’t seen much evidence of fake news like this here in Australia. Maybe it’s because those Macedonian fraudsters haven’t really bothered with the Australian market. They haven’t bothered to generate fake news stories about Malcolm Turnbull and Tony Abbott. The two of them seem to be generating enough real news to keep up the clicks.

But that’s not to say I don’t think the term “fake news” is an issue. It is. And let me explain why, by returning to this question of what is fake news.

Is it “fake news” when a politician lies, misleads or simply gets something wrong?

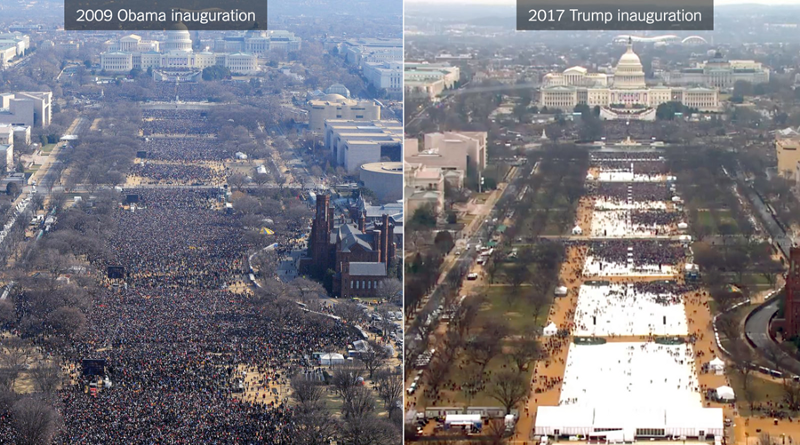

Donald Trump claimed to have the largest inauguration crowd in history until these pictures emerged …

Was the President himself guilty of “fake news”?

And what about this headline from just a couple of weeks ago:

That was according to what the US Defence Secretary and the White House spokesman were saying at the time. It wasn’t just CNN, we all reported that the carrier group was heading to the Korean peninsula. It is now, but at the time of those statements it was actually heading in the other direction.

Is this fake news? Well I would argue no. Governments good and bad get stuff wrong, either through cock-up or conspiracy, all the time. I wouldn’t put it in the category of fake news though. It’s just politicians lying or misleading or getting their facts wrong, as they’ve so often done.

What’s more of a problem to me, is how politicians themselves have latched onto the “fake news” label when trying to dismiss a story they don’t like. Donald Trump throws around the “fake news” line more than anyone when he doesn’t like a story or a journalist or a media outlet. But let’s leave him alone for a minute and look at this in the Australian context.

Is this fake news?

“Plum Postings Hobble Reshuffle Choices.”

A story from Dennis Shanahan about a possible reshuffle if George Brandis and Marise Payne are given diplomatic postings. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop labelled this story “fake news”.

Or this?

A story from the ABC’s Stephen Long about the Indian company Adani which is behind the proposed Carmichael Coal Mine, which is apparently facing multiple financial crime and corruption investigations. Resources Minister Matt Canavan labelled this story “fake news”.

And finally: “Govt MPs working to bring same sex marriage policy to a head over next fortnight”. A story from James Massola at the Sydney Morning Herald. Treasurer Scott Morrison labelled this one “fake news”.

Now I’m sure they all think they’re right in the zeitgeist using this “fake news” term. But here’s a tip for them: these stories aren’t fake news and it’s dangerous to suggest they are.

There is absolutely no justification to link entirely legitimate stories from reputable journalists to the crap from fraudsters in Macedonia and other peddlers of material designed to deliberately mislead and undermine how people are informed.

Now it’s true, the media is an easy target. Donald Trump knows it and so do politicians here. When it comes to trust, we’re regularly ranked down there with used car salesmen and even politicians themselves!

In fact we’re in even more trouble on this front than some realise. Some of you may have heard about the “Edelman Trust Barometer”, an annual global survey of trust in major institutions. Its results this year show trust in the media in Australia fell an alarming 10 points during 2016 from 42 per cent to just 32 per cent. That’s near the bottom of the pack internationally. Well below the level of trust in the media in the US, India, China and Indonesia. We scrape in just above Russia and Turkey.

Without trust we are vulnerable. Who are voters going to believe when a politician labels as “fake” a story they simply don’t like?

So what can we do about it? Well at least when it comes to politicians calling legitimate stories “fake news”, I reckon we should call it out. Even if it does mean defending one of our competitors, heaven forbid!

I’m not a supporter of media collectivism. I like the robust political media landscape in Australia, the wildly different voices and the healthy competition. I don’t think we need to start holding hands, but there is an argument for some solidarity when it comes to defending our craft right now.

If a competitor’s legitimate story is labeled “fake” by a self-serving politician, call it out. Don’t let trashing journalism become a go-to response for those politicians who can’t mount a better defence.

The bigger question is what can we do to restore trust in the media. Particularly in my context, trust in political journalism. Let me be clear, I don’t have a magic bullet answer to this. No one does.

But I do think it’s important to understand what’s driving audience cynicism.

Back to basics

As many have noted over the years, audiences are fragmenting and retreating into bubbles or echo chambers on the left and right. Once upon a time you had the choice of a few TV channels to watch, a few radio stations to listen to and a few newspapers to read.

Now you have infinite choices. You can listen to, watch and read an entirely right-wing perspective or left-wing perspective on the world. And many do.

They are attracted to stories and commentary they agree with.

Journalists need to be journalists, not players. Not Twitter warriors.

Facebook and Twitter help create these bubbles — by feeding them the news and opinion they want. The business model for most media outlets is also shifting to accommodate this trend. It’s not hard to understand why. Commercial media outlets live in a commercial world. People want informed opinion and they want commentary. There is no disputing that.

But there is also I believe, a vital role for journalists who try as hard as they damn well can to be straight down the middle and hold both sides to account. To ask tough questions of those in every political party, the big ones and the little ones, to uncover uncomfortable truths and yes, tell audiences what they might not like to hear or necessarily agree with.

Journalists need to be journalists, not players. Not Twitter warriors.

If you want to be trusted as a political journalist, play it straight. If your media organisation values trust, they will thank you for it. Don’t be swayed by the outrage industry on social media.

Admittedly this isn’t as easy as it sounds.

For what it’s worth — after 17 years in the Press Gallery — I reckon this is actually harder than ever right now but also more important than ever.

The advent of social media has delivered many wonderful things — but also a torrent of daily abuse aimed at journalists. Nearly every day my lovely Twitter followers call me either a “lying Labor dog” or a “right-wing Murdoch puppet”. Some of it can even get a lot more colourful than that.

My advice to those who are bothered by this stuff: either ignore it or wear it as a badge of pride.

In fact, I like to believe there’s a real opportunity for journalists right now to re-engage with cynical audiences. And largely by getting back to basics.

I know plenty of people have said this since the Trump victory and Brexit, but it’s true: get out and talk to a wider group of voters than those you usually mix with. Don’t just rely on polls and talkback radio to “get a feel” for the mood.

I’ve picked up more insight into what Australians really think over dinner in an RSL club or at a campground with the kids than I would in a week talking to the political spin doctors in Canberra. Now I appreciate there’s little time or money in most media jobs these days to wander around chatting with “real Australians”. The news cycle is relentless. But as individual journalists and as an industry, we need to maintain that connection with the communities we’re representing.

Transparency

The second serious challenge for political journalists I see is transparency. Or the lack of it. We’ve probably become too complacent about this.

The most glaring issue when it comes to transparency in government in Australia is the secrecy in Defence. There’s no other way I can put it.

8 years ago I was embedded with Australian troops in Afghanistan for a week. We travelled around forward operating bases in Oruzgan and I was able to talk to troops on the frontline openly.

The ABC and many others had similar opportunities. Important stories were told and history was recorded about what the men and women of the Australian Defence Force were doing in our name. These media visits weren’t as regular as some might have liked … and certainly a long way short of the media access the American military provided, but it was something.

In August 2014 Australian troops were sent back into Iraq to help in the fight against Islamic State. Apart from an initial flurry of coverage when they were first deployed, we now hear very little.

For nearly 12 months I’ve been requesting a visit to tell the story of what Australian troops are now doing. I’ve had no success. We get a briefing roughly every 6 months from an official in Canberra, and the Defence website pumps out press releases and lovely photos from its enormous media wing.

But when was the last time you saw our soldiers in the field telling their story? When was the last time you saw the Chief of Defence do an interview?

Early last week when Australian troops were caught up in a chemical weapons attack by Islamic State in Mosul. We found out initially through the American media! Fortunately no Australians were hurt. But why aren’t we told about this? There’s a hell of a fight going on in Mosul and we haven’t had one briefing about it.

Now it’s true, there aren’t as many specialist Defence reporters as there once were. There aren’t as many journalists devoted to finding out what’s going on in Defence and that means there isn’t as much pressure being applied.

But there’s also no doubt the Australian Defence Force has become media shy over the years. It’s a shame, because one day Australians will want to know what we did in Iraq. And they deserve to know.

Then there’s the immigration department and its offshore processing centres. They’ve been running for four years now with barely any media access.

Admittedly a few have been able to access the processing centre at Nauru. But not Manus Island. The Australian Government hides behind the excuse it’s up to Nauru and PNG to decide media access, as if the Australian government has no influence or responsibility to allow some transparency around what’s going on in these places.

Preventing media access of course means the plight of the asylum seekers and the impact these centres have on the local community is out of sight and out of mind for most Australians.

It also makes it extremely difficult to examine why certain incidents occur.

Take the incident two weeks ago — when PNG Defence personnel fired around 100 shots into the Manus Island centre. Last week the Immigration Minister Peter Dutton told me on my program that one of the reasons tensions were running high was because three asylum seekers were seen leading a 5-year-old local boy into the centre.

The local PNG Police commander seemed to disagree, saying the Defence personnel were drunk and that the shooting followed an altercation on a nearby soccer field. A boy aged 10 had come to the centre a week earlier looking for food. Peter Dutton is standing by his version of events, which he says is based on departmental advice and other contacts on the ground.

I’m not judging who’s right and wrong here. But there is a discrepancy and this isn’t a trivial matter.

Now if we did have more media access, I’m not suggesting we’d all have permanent correspondents based in Manus Island. But when a situation like this comes along, where asylum seekers claim there’s an unfair insinuation that paedophilia is going on and when there are fears about what this could do to an already volatile situation between some locals and the asylum seekers, surely allowing journalists in to talk to all sides and accurately report what’s gone on would only be a good thing.

As for transparency closer to home, consider this. We live in an information age. You can find out almost anything you want to know about everything with the device in your pocket. Except how the thousands and thousands of dollars in tax you’re paying each year are being spent.

Sure, we get the federal budget each year that tells us broadly where the money is going, but why not an online real-time portal that taxpayers and journalists can click on and find out where their money is going without having to lodge freedom of information requests?

A number of states in the US have done this, including Texas, which has a population greater than Australia’s. The Texas site is terrific by the way, you can drill right down and see how much is being spent by public servants for example on meals and lodging (roughly $5.5M a month in case you’re wondering). Each individual expense is recorded.

Don’t think for a minute this data isn’t being recorded here already every day. It is, but we just don’t get to see it.

As for transparency around what our politicians are up to, the Prime Minister’s recent reforms to MP expenses are a good step. Forcing them to report every month rather than every 6 months on what they’re spending is a good move. I just wish they’d get on with it.

But what about some transparency around political donations? Why can’t we get a report every month (or in fact in real time) when donations are made to political parties? The Queensland government is rolling out this reform this year. Why isn’t the federal government? Labor says it supports the move. Malcolm Turnbull says he has no in principle objections either. So why isn’t it happening?

And while we’re at it, why don’t we get a daily on-the-record briefing from the Prime Minister’s office? Everyone loves to make fun of Sean Spicer, but at least the Trump Administration is trying to uphold the fine tradition of the daily White House briefing.

Surely some eager junior minister, or Chief Press Secretary Mark Simpkin himself could stand up each morning and explain what our government is doing each day.

Even in the mother of Westminster traditions, Prime Minister’s Questions are followed by a thorough briefing, usually by the chiefs of staff to explain to the press the arguments each side was prosecuting.

Perhaps politicians would have less reason to attack the press and accuse us of writing “fake news” if they opened up and shared more information with us.

Transparency does matter. And even though Malcolm Turnbull likes to talk about being agile and innovative (or at least he used to), transparency in the Australian government is not keeping up with global trends.

To be honest — it would probably help the standing of politicians if they were more open and accountable. And it would probably help the standing of journalists if we fought harder for it.

So in conclusion …

My message tonight is don’t worry too much about the threat of fake news stories getting more Facebook shares than your own. But do worry about the standing of our profession. And do something about it.

Stand up for your colleagues when politicians are trying to rubbish their work. Always fight for greater transparency to shine a light on areas governments would rather hide. And be proud of straight news reporting. If we want to be trusted as journalists, we have to be journalists first and foremost. Not opinionated Twitter warriors.

I’ll leave you with a quote from a politician, but a good one. Abraham Lincoln: “I am a firm believer in the people. If given the truth, they can be depended upon to meet any national crisis. The great point is to bring them the real facts, and beer.”

Read Walkley Magazine content online here.

The Press Freedom Dinner raised funds for The Media Safety and Solidarity Fund.

This is the MEAA's Annual Report into Press Freedom in Australia