1993-4, Dagenham, United Kingdom

Marion Jones: 'I want you to know that I have been dishonest', Apology for Steroid Use and Dioshonesty - 2007

10 October 2007, USA

Good afternoon everyone. I am Marion Jones-Thompson, and I am here today because I have something very important to tell you, my fans, my friends, and my family.

Over the many years of my life, as an athlete in the sport of track and field, you have been fiercely loyal and supportive towards me. Even more loyal and supportive than words can declare has been my family, and especially my dear mother, who stands by my side today.

And so it is with a great amount of shame that I stand before you and tell you that I have betrayed your trust. I want all you to know that today I plead guilty to two counts of making false statements to federal agents.

Making these false statements to federal agents was an incredibly stupid thing for me to do, and I am responsible fully for my actions. I have no one to blame but myself for what I have done.

To you, my fans, including my young supporters, the United States Track and Field Association, my closest friends, my attorneys, and the most classy family a person could ever hope for -- namely my mother, my husband, my children, my brother and his family, my uncle, and the rest of my extended family: I want you to know that I have been dishonest. And you have the right to be angry with me.

I have let them down.

I have let my country down.

And I have let myself down.

I recognize that by saying that I'm deeply sorry, it might not be enough and sufficient to address the pain and the hurt that I have caused you. Therefore, I want to ask for your forgiveness for my actions, and I hope you can find it in your heart to forgive me.

I have asked Almighty God for my forgiveness.

Having said this, and because of my actions, I am retiring from the sport of track and field, a sport which I deeply love.

I promise that these events will be used to make the lives of many people improve; that by making the wrong choices and bad decisions can be disastrous.

I want to thank you all for your time.

Bob Murphy: 'All of the laughs, the scraps, the yarns, the characters, the smells and the donuts', Norm Smith Oration - 2018

7 June 2018, Members Dining Room, MCC, Jolimont, Melbourne, Australia

So many things we love about our game have very little to do with the game itself. Perhaps like many of you in the room tonight, when I think about my love of the game, my imagination doesn’t run straight to the high marking forwards or the bone crunching tackles. My thoughts go to the taste of jam donuts and the smell of jasmine in early Spring.

My ambition was flamed watching football as a little kid in the outer and the reward for sitting through the entire game was a hot jam donut as the family began the search for the car in a sea of Commodores stretched out to the horizon. The donuts, as delicious as they were, were more than just a sugary treat. When I think back on those days now, they symbolise an optimism. “Maybe I could play in the big leagues one day...”

The exact moment when Spring hits is not always easy to judge, but for footballers it’s easy. That first whiff of jasmine in the air will tell you everything about where your season is at. If it’s been a good year, the jasmine lets you know that it’s finals time, potential glory reveals itself to you. If it’s been a bad year, the floral perfume is like a swift kick to the bollocks. There will be no big dance for you and your clan.

I was at a country wedding not so long ago and an hour before the ceremony, around the side of the farmhouse I came across one of the groomsman cleaning his R.M.Williams boots with Dubbin and a tattered rag. It moved me, to the point of tears. It reminded me of my Dad. He used to clean my footy boots with Dubbin and cloth before game of junior football I ever played.

Dad had three pieces of advice when it came to my football.

1. Hold your chest marks.

2. Man up

3. Kick with both feet.

In life, I have only one rule and I will break it tonight. DO NOT make a speech on the same night Martin Flanagan makes a speech. This is a bit like a rap battle between two pacifist, lefty, football romantics with a weakness for Van Morrison records.

I’ve got a book coming out next month, for those of you who don’t know. It’s called Leather Soul.

The theory was put to me when I was writing it that the overarching theme of the book would only emerge once it was almost complete, and I now believe that to be true. Looking back over the pages I see many arcs. A bit like chopping down a gum tree to find the rings in the timber. Spheres of time. Innocence arching all the way around to experience. A few knots of imperfection for good measure.

I’m about to turn 36 and my life can be easily split in two. The innocent, sensitive kid and the professional footballer. A couple of things have emerged out of this literary pursuit, for me anyway. One of them is the result of two opposing forces smashing into one another. My childhood was almost bereft of strict rules and schedules. As a school kid, my only real practical use for time and a clock was the understanding that I had to leave the house when the microwave read 8:21am. If I walked out the door at precisely that time, I would meet my school bus as it rounded the bend. A minute later and I would have to walk all the way to school and risk being late.

I was, in some ways, quite bohemian for a teenage boy in a conservative country town with a bowl cut hair do. I was free. I went from that straight into the cut-throat system of a professional football club. Rules, uniforms, routine and then more rules. It was a shock to the system. Professional football clubs can feel like the army in more colourful uniforms. I took a while to find some breathing space in its confines.

If my childhood and upbringing were easy, my football career was anything but. Every team, every player in the league is always trying to prove a point, and I suppose I was trying to prove that I could endure. Was I tough enough? Playing on in 2017 was clearly about one last chance at a premiership, but more than that I wanted to show people I could come back from a knee at 34 years of age and still mix it with the best. Who was I proving a point to? I’m not so sure. Maybe myself. I feel content that I ran the tank dry.

One of the rings in the gum tree was the draftee who nestled under the wing of the elders of our club at the time. Guys like Luke Darcy, Ben Harrison and Simon Garlick guided me with a firm but steady hand, and they gave me shelter from the storm. I was caught off guard by the paternal instincts that awoke in me when I had become an elder myself, and it was under my wing that I could provide similar refuge for the next generation. Young blokes like Easton Wood and Jordan Roughead were given everything I had and everything that had been handed down to me. The lineage of the locker room and the battlefield.

I was lucky to play alongside good men for much of the way. Maybe as a reaction to my gypsy hearted ways, I gravitated to blokes who you could set your compass to. Daniel Giansiracusa and Matty Boyd were like my north stars for years. A focal point to keep my ship on course. I always felt a sense of comfort walking up the race and seeing those guys next to me. That’s almost the highest accolade a teammate can bestow on another I reckon.

I’ve always been a fan of the great players. I got to play with so many, but Chris Grant and Marcus Bontempelli stand out. Complete players. Stars. That’s something to tell the grandkids. For all the nonsense in the analysis of the game, most of us still acknowledge that the special ones move differently. Something in the nuances of their play sets them apart from the rest of us.

Granty’s ability to pick up the flight of the ball in the air and mark it in front of his eyes with perfect timing – with danger all around – always left me feeling lucky to have such a close vantage point. Watching the Bont create a path in the chaos of play with his big frame has already become a trademark. Playing alongside him, I could hear the appreciation in the outer from our own supporters. It was even more graceful from a few feet away. With the ball in his hands he’d lope away in slow motion, like he was wading through waist-deep water, the sea of stragglers falling away in his wake, one by one. A football Moses. Or Jesus. Definitely biblical.

You’re not meant to meet your heroes, at least that’s how the old saying goes, but that didn’t ring true for me. I only met Robbie Flower a few times, but each time I left shaking my head, astonished by his gentle, easy manner. His lack of ego, in stark contrast to so many of his 80s contemporaries. A sweet man. A hero to any skinny bloke who has ever pulled on a jumper.

In the Murphy family, we supported three things. Paul Keating, Peter Daicos and the Richmond Tigers. Matthew Richardson and Wayne Campbell, along with a few of my Tiger heroes, have always been generous to me. They indulge all of my teenage questions and fascinations. They’re just my mates now, I guess, and that blows my mind, but I reserve some of that little kid’s awe and wonder. I think they secretly get a kick out of it too.

From a half back flank I got to watch the game over the shoulder of some of the very best players the game has seen. I spent an unforgettable night chasing with Stevie J and trying to keep pace with his verbal entertainment too. In the dying minutes of a close game the ball shot out of the centre square and I lunged to spoil it, but like a true cat he was after it again. He took the ball with me closing in and hand balled over his shoulder whilst looking the other way. His handball hit the mark and it resulted in a goal. Game over. Stevie waddled up next to me and I knew it was coming, “I usually save that shit for finals”. He was the best flanker I played on.

I had a few scraps along the way. Football is a bit like the jungle, every so often something or someone surprises you and takes you down. As I lay on the back of the motorised cart having just done my knee for the first time a young Collingwood supporter, no more than 10 years old, leant over the fence and screamed in my face, “Hey Murphy, you fucked my dream team!” Despite his youth, it did feel a bit harsh.

Family circles spin around this exposed tree stump like a vinyl record. Mum’s adventurous spirit runs through me like a mountain stream. I remember at various points of Bulldog crises she would give me a pearl of wisdom. My favourite was, “Don’t wait for the wind, grab the oars!”

My first football memory is being placed in front of my older brother Ben as my sister Bridget kicked the ball high above my head. Ben would scream “CAPPER!!!” and wrap his legs around my head as he attempted mark of the year, over and over again. I was four years old. That was my role in the team at the time.

Reflecting on the book when the last words had been written, I couldn’t ignore the fact that much of my story is about a father and a son. Dad and I watched the stars of the game from the outer at Waverley Park and I took him with me onto the field as I got a closer look over 18 years with the Bulldogs. It might be a long bow, but I felt like he was with me as we watched all the great players from this era within arm’s length, and for brief moments, teased at being a great player myself. I hope Dad feels like that too. Whatever I was on the field, I offer it up to my Dad as a gift for cleaning my boots every Friday night.

Family has broadened as I’ve gotten older too, of course. If you play for long enough – and I was blessed to play for a bloody long time – the relationship with your club changes. For a time your footy club is who you play for, and then at some point that club is a part of you and you are a part of it, linked forever. Like family. I love the Bulldogs. It might read as a throw-away line, but it’s a love that I would never mask behind any sort of ambiguity. Footscray and the Whitten Oval will always feel like home.

I have much to be grateful for, not least the chance to actually play, but one thing that jumps to mind is the notion of loyalty. It’s seemingly a fading currency in professional sport, or so I’m told. Loyalty in sport isn’t dead, just a little misrepresented. It’s not blind loyalty. Too much is at stake. The loyalty I’ve known in footy is a relationship – there must be an exchange of effort and goodwill. The Bulldogs and I were a good couple. I gave them everything I had. I hope they feel like they got a good deal, too. I’m a proud servant of the Bulldogs. Forever.

My book was never going to be titled MURPHY. I wasn’t that sort of player, and I didn’t have that kind of career. For a long time the title I had in mind was A Footballer’s Lot. Much of the book is a collection of stories of a footballer, that footballer just happened to be me. There were many other titles ...

I suppose it would be good manners to tell you that I never saw myself writing a book and that this “just kind of happened”, but that’s not true. After being encouraged many years ago by one of my heroes and my co-speaker tonight, Martin Flanagan, to write a different kind of footy book, I set my co-ordinates to doing just that. My hope was that this book would fill a gap. As a footballer, I was neither a champion nor a notable disgrace. The risk was that I wouldn’t have a story to tell. That in itself I found interesting, the notion of writing a footy book that shone a light on the middle ground. The highs and lows of a life in footy, the feel of the bumps along the path from inside the middle of the pack.

Then I became captain of the Bulldogs. A young football team caught fire, a club emerged from obscurity, and then something else happened. I’m still not entirely sure what that “something” was, but I know it involved a lot of hugging. I don’t know if we changed the game, but for a brief moment the Bulldogs were hip. There was a story.

It’s funny, but I’d never felt a part of my generation before that time. Even when I was a teenager at the underage disco, all the kids were screaming the words to grunge anthems like Smells Like Teen Spirit and Killing In The Name Of. Plenty of the kids were from broken homes; they meant it, they felt the songs in a way that I didn’t. I was secretly hoping the DJ would play the Beach Boys ‘Good Vibrations’. I enjoyed an angst-free world. A charmed childhood.

Regrettably, I spent much of my footy career either writing or daydreaming about footy, music and clothes from another time. Living in a cartoon world of nostalgia. And then my football club was thrown into crisis at the end of 2014, and I woke up. My three years as captain, I felt alive. I felt present. All the chips were on the table. There was a sense of desperation and defiance in the air. It was a “damn the torpedoes” kind of vibe. Every moment felt important. It was an exhilarating ride.

During the low ebb of October 2014, one inescapable thought kept throbbing in my head: “My football career has meant nothing.” It was a depressing thought. Fifteen years of getting to the line and the club was ultimately in a worse place than ever. And then something magical happened. I look at those last three years as a trilogy. The rise of `15, the glory of `16, and the struggle of `17.

The 2016 Premiership and “that” medal moment with Luke Beveridge are like a mountain in my life. But just like Uluru, the colour of the mountain changes in the light. On most days I see a beautiful landscape. A football fairytale rising out of the ground pointing towards the heavens. But there are other days too. There are times when just the memory of that day and that moment break my heart in two. Even now, I still brace myself when a stranger starts up a conversation with me about the premiership or the medal. I’m scared of what they might say. It all depends on the shade of the mountain on that day.

Writing a memoir demands a level of candour. It’s only recently I’ve come to accept that my greatest day in football was Grand Final day in 2016. But I must also acknowledge that my worst day in football was the very same day. As a leader of the club at that time I was so proud, the euphoria was so real. But I’m a footballer and I was not where I was meant to be. I felt that in my marrow. I will never get over it.

For a time, “Almost” was another title option, but it’s black humour might have been too obscure. On those dark days, it helps to remind myself that despite the twinges of heartache, they are nothing compared to that sense of being unfulfilled in 2014. I sit back now knowing that, at least, it meant something.

When you join a club you inherit its history, its mythology. There’s been a heavy load to carry in that regard if you chose to be a Bulldog. Survival and fightbacks aside, our one shining light was the premiership of 1954. It was so long ago that the only footage of the day is fuzzy and incomplete. A bit like a football Zapruder film. “Back and to the left”, another good title option now that I think of it. That premiership and its own mythology grew over time, the walk to the Footscray Town Hall became something of a metaphorical pilgrimage. These stories were glorious, but weathered, aged.

I felt at the time that the 2016 premiership healed a lot of the pain of our football club. Since 1954 there were so many losing seasons. Too many. The history books give us the ladder and the checks and balances of the wins and losses, but those columns don’t accurately record the emotional damage all of that losing causes. Too many people have left our footy club unhappy or bitter. There was something special about the 2016 team that brought a lot of people back and seemed to rekindle the love and attachment people once had for the club. All of us who have spent time at the club since 1954 had daydreamed about what it might look like if we won the flag again. What would a sea of Footscray supporters at the Whitten Oval look like the day after the battle was won? The reality was better than our dreams; how often can you say that in life?

After the historic presentation of the cup to the Bulldog people at our home ground, the inner sanctum of the club and their families came together at the Railway Hotel in Yarraville. That was special, too. So many beautiful people. So many characters with big hearts. That team, that finals series, felt like a shooting star. Magical. I was privileged to be amongst them. On the Monday, just the players reconvened at the same pub and things were, as you’d expect, pretty loose. It was still early in the day when I thought, as the oldest player, that a speech should be made.

I stood on a stool, pint in hand, and talked about the significance of history. I opined that some of the players with a medal around their neck might have some comprehension of what they’d just done, and maybe some of the older ones would have an even broader appreciation. But I told them to leave a bit of space for the possibility that it was even bigger than they thought. This premiership, for some long-suffering Bulldogs people, means they can actually die happy. I got down off my stool, content that I’d nailed it, and Matthew Boyd sidled up next to me. “Bit fucking morbid bringing dead people into it, don’t ya reckon?” I’ll miss that about footy clubs. Brutal truth.

Someone asked me recently what life was like having just retired from the AFL, and I told them it was a bit like leaving the Big Brother house after 18 years. The hyper-focus the game demands is now gone. It’s eight months since I last ran out as a player for the Dogs, and it’s starting to show. When I look at my legs both of my knees are lined by scars. The physical toll of the game has left harsh slashes across the flesh. Dermott Brereton once said that if you played more than 200 games of league football you had a daily reminder through some kind of physical ailment. He’s right, of course, and I limped to 312.

Both of my knees ache a bit when I go for a run these days, but I manage well enough once I get going. My toenails are yellowed and gnarled like bamboo from years of punishment, and the hint of a gut is starting to show, but it’s my neck that gives me the most grief. A “popped” disc in 2010 did the damage and it’s never fully recovered. Uncomfortable as these ailments are, they’re badges of honour too. I gave the game a pound of my flesh. There will be no comeback

If I look back again inside the circles of the fallen tree, I see two kicks. The first, a wobbling, floating, mongrel that came off my boot in my very first game against the Blues at Princes Park, and somehow went dead straight to put us in front deep in the last quarter. That glorious line turns all the way around the wood until it comes to meet itself some 18 years later. My last game of footy. With the game tightening, Lachy Hunter feeds me the ball and I see space in front of me. My heart lifts as I sense the moment. I could turn this game on its head, bring us back into the contest with a running shot from just inside the 50-metre line. I swing my leg through and it makes the sound of a bum piano chord. It could very well be the worst kick of my career. Off the side of the boot and into the stands, I get the Bronx cheers from the Hawthorn supporters. It’s my last ever touch in a game of footy.

My last kick was the kick of a man whose best days were long gone. I was done. If I were a racehorse at that point, they would have pulled the white sheet across and destroyed me at the track. If I’d kicked it sweetly, post high through the middle, I might be wondering if I should have played on. But I’m not. I don’t want to play anymore, I don’t have it in me anymore to get to the line. That’s a relief. I’m sure there will probably be little moments where I’d love for certain things, pine for the contest or the chase, the sweet kicking musical moments, but that’s life. I had my time.

And it was a wonderful time. I was the kid who played the game in the street until dark, dreaming, yearning what it might be like to actually play in the big league. And I did it. It was harder than I thought it would be, much harder. But to quote Tom Hanks in A League Of Their Own, “Of course it’s hard – it’s the hard that makes it great!”

I wasted a school education wondering what it might be like to play on the MCG in the fading light of an autumn Saturday afternoon with the game in the balance, and I did that. It was beautiful. Better than I could have imagined. The game hardened me, thickened my skin. For all of my idealistic babble about being a kid free of stress and full of adventure, I was a young adult that was almost bankrupt when it came to accountability. That can wear people down, and I wore a few out. The game beat some reality into me. Taught me about discipline and responsibility.

It also gave me moments to savour forever. Minutes before every game I played, I’d make my way into the trainers’ room and stick some Vicks up my nose. It was about putting on the armour. In those final few moments before you take the field you morph into a different character. What some people might call “white line fever” takes hold, but it looks and feels different for everyone.

The fever doesn’t turn everyone into Robbie Muir or even Glen Archer, but it puts you on edge. The fight or flight response fills your stomach and stretches out to tingle your fingers and toes. Your mind walks the high wire between loneliness and a deep sense of brotherhood. You’re a gang. The feeling is precious and pure.

The changerooms are quiet, but I can hear the frenzied noise of the masses in the distance, just beyond the concrete walls. Time moves like glue as the anticipation builds. To pass the time I pace the room, slap my hands together, put an arm around teammates to offer some words of comfort. I press resin into my hands and spread it around my palms so the ball will stick in my grip.

Despite the tension and storm clouds on the horizon, I try to keep a calm facade. I try for an easy smile to ease some of the tension in the room, but inside I'm like a pinball of thoughts, hopes, fears.

Someone gives the signal and we come together briefly with our coach. He gives us a final message. It doesn’t really matter what he says, it’s the symbolism of the picture. We are his boys. He’s with us. We break the tight circle and turn for the door. The noise grows louder.

As captain I get to walk out first, and the sense of pride and privilege never gets old as I look back on the team we have. My boys. Our support crew and a few ex-players line the walls respectfully as we leave the rooms and begin our ascent to the field. It’s the greatest feeling in the world. I walk slowly up the race, savouring the moment. Gradually picking it up to a jog as the field of play comes into view, we explode onto the ground as a team and our clan rise as one with us. Our theme song comes from the old sea shanty, “Sons of the Sea”, but we are the Sons of the West, and our tribal hymn blasts out across the stadium. We are snarlin’. You can’t touch us now. This is our childhood dream, and we’re all living it.

Now that I can’t play anymore, I know in my heart it’s these precious seconds that I miss the most.

I was a young, naïve kid with a brand new football in his heart. Over time, the leather aged from the bumps along the trail. The elements of Footscray winters and some glorious liniment-scented afternoons. All of the laughs, the scraps, the yarns, the characters, the smells and the donuts. The game. They all left a mark on me, on my leather soul. I wouldn’t change any of it.

Bob Murphy’s autobiography ‘Leather Soul’ is available through BlackInc books.

The companion oration to Bob Murphy’s is Martin Flanagan’s speech on the same night. It is also magnificent.

“People ask me who I barrack for - I barrack for the game. An American who lived in this city for some years once wrote me a letter which began: “You seem an intelligent man. Why do you write so much about football?”. Because it’s the culture I’m from. Footy’s a language I can speak.”

Kurt Fearnley: 'An athlete whose sport has been born out of the back fields of rehabilitation hospitals', Sport Australia Hall of Fame, The Don award - 2018

If I could take a moment to acknowledge a few people, the family of Sir Donald Bradman, his son John, and his grandchildren, Greta and Nick. The chairman of Sport Australia Hall of Fame member and legend John Bertrand AO, the selection committee chairman Rob De Castella AO MBE. Sport Australia Hall Of Fame members, board members, dignitaries, sport leaders, ladies and gentlemen.

The fellow 2018 Don Finalists, Madison de Rozario and Lauren Parker, two of the strongest people that I know, and also people that I value not only as my peers but also as my friends.

To Sam Kerr and Ellyse Perry… two people within our community that we just know there will be statues built of them, so generations will be able to learn about your journey.

Will Power and Daniel Ricciardo… They fly the Australian Flag in places we rarely get to see, and you just feel proud that they are out there fighting.

And to Mark Knowles, who is one of the most truly decent people that not only I have been able to share the Australian uniform with and stage with but someone who I feel grateful to have even crossed paths. It’s an honour to share this role as The Don finalist with all of them.

Apologies for my absence, I am in Chicago, I am competing, but more importantly I am spending time with my wife, Sheridan and my boy Harry, and my little girl Amelia, who have seen me at a distance for far, far too long.

I grew up with an understanding about The Don and it was as much about integrity and humility as it was about excellence in sport. And I recognise tonight that I am the first within our Paralympic movement to hold up this prestigious award, but I have no intention of self-congratulation, I have to point back behind me to the generations of proud men and women with disabilities who allowed me to become the person and athlete that you see fit to receive this award.

An athlete whose sport has been born out of the back fields of rehabilitation hospitals. That was created by men and women who had the desire to see not only what was physically possible but was humanly possible.

I’ve heard the stories of Paralympic forebears who speak about losing friends, who felt too much shame in their experience with disability - and that is within our own community. There was too much shame and there wasn’t enough hope. So our sport was born out of that hope. Hope that somebody can be judged by substance and not image. That the difference that we each hold can be celebrated and not used to be segregated.

Through the medium of sport that’s what our movement represents…Hope.

Hope, that if sport can adjust to include those with disabilities, maybe the community can follow. And when our community is shifting to this idea of perfection where life, within even a picture, is filtered within an inch of humanity.

Our movement has greater importance than ever because the image of perfection isn’t real, it’s not sustainable and it’s not healthy. And our ability to share beauty and strength in this perceived imperfection, it just cannot be matched. I fundamentally believe that sport can lead this country and I believe the Paralympic movement is a jewel within the sporting crown.

I know that there’s a few people out there now saying I should just accept this award and bugger off. But sport within this country has never been about the individual… It’s been about the uniform leading.

I recognised earlier that I am first that I am the first within the Paralympic movement to receive this award, and I am incredibly grateful to have been given this opportunity – but I will guarantee that I won’t be the last. But we need every person within this room to embrace our community of people with disabilities, not only on the sporting field but within administration, in executive and within board and in governance roles.

Let’s lead the way. We won’t regret it. There is strength and substance in this community. Enough to build a country on.

Sir Donald Bradman once said that athletes who receive recognition, they also have a duty to mankind. Well I am honored to receive this recognition and I am honored by ‘The Don’ Award and I will do my best to be worthy of it.

Matt Quatermaine: ' Thinking of you West Coast Eagles' (with apologies to Martin Flangan), Footy Almanac Grand Final lunch - 2018

28 September 2018, Melbourne Hotel, Melbourne, Australia

Eagles devotee Matt Quartermaine performed this peice for The Footy Almaanc Grand Final Lunch. The Alamanc is a community of writers and sports lovers started by sportswriter John Harms (author Play On, Malarkey Press) . The piece is a parody of Martin Flanagan’s beautiful Thinking About piece, performed by Martin on SEN a week earlier.

Thinking of you West Coast Eagles who came to Melbourne in 1987 the same year as me.

Thinking of you my brother Simon, who was one of the Eagles fans who chartered a plane in 2015 when their Grand Final was over in the first quarter.

Thinking of you Ross Glendinning - barrel-chested champion and first Eagles captain who has a medal named after him and WILL decide who gets it.

Thinking of you John Worsfold Premiership captain, premiership coach and Chemist, hired by Essendon to fix their drug culture.

Thinking of you Paul Peos because no one else will.

Thinking of you Brett Heady who they nicknamed Jobby because... it's a football team.

Thinking of you Ben Cousins, a player so shy he'd rather swim across the Swan River than talk to a policeman.

Thinking of you Scott Cummings because you now look like you ate half your team mates.

Thinking of you Bon Scott - choking back the tears and a little bit of vomit.

Thinking of you Michelle Sweeney - who has nothing to do with the Eagles but she was the prettiest girl in primary school and I still think about her.

Thinking of you Perth the most isolated city in the world because Adelaide is 2,200kms away and they want to know if they can be more isolated.

Thinking of you Barry Cable trapped under a tractor and didn't have a footy to handball into the gear stick to move the tractor forward.

Thinking of you Polly Farmer the footballer and the freeway with easy east/west travelling across the city of Perth.

Thinking of you Chard Haywood- because only in Perth would Dudley from Number 96 get a chat show.

Thinking of you Lillee when you caught Marsh sneaking a ciggie behind the nets and both of you went to put a bet on.

Thinking of you Kim Beazley governor of WA who I spotted after the 2005 grand final wearing a Sydney Swans scarf. Boo.

Thinking of you booing because it gives everyone over East the irrits.

Thinking of you Sir Charles Court premier of WA 1974 to 1982 who pronounced the state WEStern Australia and sent a convoy of drilling rigs and police across a picket line to drill on sacred Noonkenbah land and start the mining boom.

Thinking of you Jan De Jong, Dutch underground war hero, former chief instructor to the SAS and at who's Ju Jitsu school I trained and still got beaten up by bullies.

Thinking of you Rolf Harris the boy from Bassendean- Who tied a kangaroo down sport and then may or may not have interfered with it.

Thinking of you Indian Ocean where the water is wee warm.

Thinking of you Karl Langdon - Na I'm not really thinking about Karl Langdon.

Thinking of you Winged keel of Australia II which won the America's Cup and enabled millionaire owner Alan Bond to bypass building codes and construct a monstrous hotel right on the Scarborough beach foreshore.

Thinking of you Dirk Hartog, Dutch explorer, who in 1616 landed on Dirk Hartog island. Coincidence? I think not.

Thinking of you Skylab which NASA chose to crash a to earth in WA where it wouldn't hurt anyone.

Martin Flanagan: 'Thinking about you, Ron Barassi', Demons monologue - 2018

Martin was a guest on episode 26 of the podcast, telling stories about the people in this speech in advance of 2021 Grand Final

20 September 2018, SEN radio, Melbourne, Australia

This stunning radio monologue was aired on Andy Maher’s Afternoons show on SEN, 20/9/18, before Melbourne’s do or die Prelinminary Final against West Coast.

Thinking about you Tom Wills and how it started with you 160 years ago, the oldest football club in the world still playing in the elite competition of its code.

Thinking about you Ivor Warne Smith, the best player my grandfather, a working man, ever saw. That was in the early 1920s – you were playing with Latrobe in Tassie. Later, you won two Brownlows with Melbourne. Still later, as chairman of selectors, you were the steady hand behind the volatile Norm Smith as Melbourne powered to six premierships.

Thinking about you Ron Barassi, how you were brought up by Norm Smith after you father, a Melbourne premiership player, was killed in action during World War 2. You were the game’s great moderniser and after you left Melbourne for Carlton in 1965 the Dees never won another.

Thinking about you Brian Dixon, how you played on the wing in five Melbourne premierships and then spent the next 50 years working to make Australian football an international game, how you were dismissed as an eccentric, just like Tom Wills was.

Thinking about you Ron Barassi, about interviewing you and raising the oft-told football legend that you invented handball as an offensive weapon at half-time in the 1970 grand final and you smashing the table with your big fist and crying out, “That is not true! Len Smith invented handball at Fitzroy in the 1960s!”. Part of what made you great was that you had a blazing inner truthfulness.

Thinking about you Robbie Flower, and going to the footy late in your career with Paul Kelly and seeing you get caught with the ball - Robbie Flower never got caught with the ball! – and Paul Kelly writing a piece on mortality and how the end comes to us all.

Thinking about you Sean Wight, wrongly called Irish by the Melbourne fans when you were actually Scottish, thinking about your epic clash with Dermott Brereton in the 1987 preliminary final, of the mark you took over Brereton in the first quarter, of the headlock you slapped on him when it got nasty.

Thinking about you, Jimmy, running across the mark in that game and the morgue-like silence that followed Buckenara’s goal that gave Hawthorn victory after Melbourne had led most of the day. Thinking how you told me you fled to Paris and on the Metro a man lent forward and said, “Aren’t you the bloke who ran across the mark in the preliminary final?”, and you knew you could never escape it, you’d have to go back, and you’d have to do better than you’d ever dreamed of doing to atone for your error. Four years later, you won the Brownlow. You told me you won the Brownlow because you ran across the mark. That’s how your mind worked, Jimmy. Each obstacle was an opportunity.

Thinking about you Jimmy - when you were dying – going to Yuendumu and the Warpiri tribal lands five hours north-west of Alice Springs because Liam Jurrah came from Yuendumu and, as club president, you’d told the Melbourne players you wanted to see the place every one of them was from. Everyone knew you were dying. The Warlpiri people were in awe of your act and I saw how whitefellers can pass into the dreaming of this land.

Thinking about you Liam Jurrah, taking the 2010 Mark of the Year, tumbling over the top of a pack in Adelaide, up so high you took it on the way down as you fell head-first to the ground and the commentator crying that one name, that one word, so that it reverberated around Australia: “JURR-A-A-H!”

Thinking about the night in the Long Room at the MCG when Liam Jurrah’s grandmother, who had come down from Yuendumu, addressed a club function in Warlpiri. Her language. Thinking about Liam telling me that, once when he had an injury, his grandmother and some other Warlpiri women elders sang it away.

Thinking about just how low Melbourne were at the time when Jimmy came back as president, thinking about their courageous captain James MacDonald, a slight man who seldom spoke but could knock you into next week with his hip and shoulder.

Thinking about you Andrew Mamonitis. The Dees were in serious debt and struggling for sponsors and Andrew Mamonitis was in a Kazakhstan restaurant in Moscow attending a meeting being run by the Russian internet company Kaspersky and a senior executive with the Oriental name of Harry Cheung invited ideas from the floor and Andrew Mamonitis made a pitch on behalf of a club playing a game no-one had heard of, saying it was a way for Kaspersky to enter the Australian market, and Harry Cheung got Kaspersky's Asian representative, a Swede called Povel Torudd, to ring the club and the club put Povel Torudd through to membership inquiries but Povel Torudd persisted and, eight days after Andrew Mamonitis made his pitch, Harry Cheung flew to Melbourne and clinched the deal.

Thinking about my friend David Bridie, about his steadfast support of the Melbourne Football Club and the people of West Papua and how I know this side of the grave he’ll never give up on either. Thinking about his daughters, Winnie and Stella. Feminist Demons.

Thinking about the woman in the cheer squad I sat behind and the kindness she showed the young man with the intellectual disability she was sitting with. Thinking about her offering me biscuits and a cup of tea.

Thinking about the Melbourne woman supporter I know who was taken from her mother at birth and adopted out. All she knew about her past was that she came from Melbourne so Melbourne became her team and in no-one does the heart beat more true for the red and the blue than it does in Penny Mackieson

Thinking about you Arthur Wilkinson, the Melbourne doorman who came to the club as a friend of Checker Hughes and was still there in 2008. As a youth, Arthur carried his swag outback and worked in the bush. All he carried with him was one set of clothes and a book of poetry. At his funeral, his son Mark said , “My father loved 3 things - the bush, my mother and the Melbourne Football club”. Thinking about you Mark Wilkinson, yours father’s successor as Melbourne doorman, standing alongside Barry King.

Thinking about you Nathan Jones and the joy in seeing a young player grow like a tree and become a champion.

Thinking about you Neville Jetta and a session I sat in on that you and Jeff Garlett ran, introducing your team-mates to Aboriginal culture, and afterwards your team-mates saying, “Why weren’t we taught this at school?”

Thinking about the match in 2015 when the Melbourne team wore wristbands in the colours of the Aboriginal flag as a gesture of solidarity with Adam Goodes.

Thinking about a day last year when Melbourne brought back Liam Jurrah, Aaron Davey and Ozzie Wannameira to launch their reconciliation action plan and they’re standing with Neville Jetta when Nathan Jones enters the room and the sound like a joyful clap of thunder as the five men embraced.

Thinking about you Big Max Gawn, how Jim Stynes spotted you early, saying you brought something special to the club, you like Jimmy being an outsider, Jimmy an Irishman, you from a Kiwi background bringing All-Black grit to the team.

Thinking about the book I wrote on the Bulldogs in 2016 and the injection they got from having fresh players return at the start of the finals and then seeing how young Jack Viney is playing, thinking about this Melbourne team and how strong and settled it looks.

Thinking about a photo I saw on Twitter of the spot in the Dublin mountains where Jimmy’s ashes are scattered, seeing a boulder with a plaque bearing his name and, draped over it, a Melbourne scarf. The red and the blue. It made me want to shout: “You’re still with us, Jimmy!”

Go Dees!

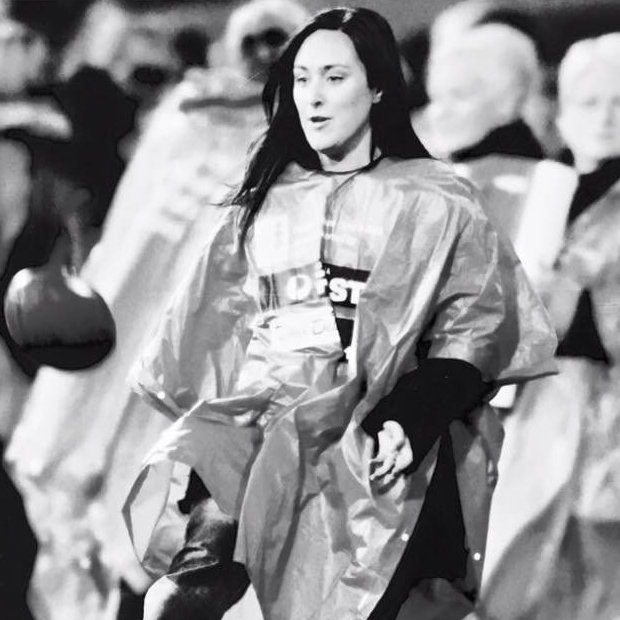

Angela Pippos: 'Why I'm feeling invincible again', Our Watch Awards - 2018

12 September 2018, Sydney, Australia

It was my holy day.

A day of ritual.

A day of sport.

Four hours before designated kick-off my brother Chris would clomp around the house in his polished footy boots, ball under his arm.

I’d be dressed in my green-and-gold tracksuit with my netball skirt over the top.

I had a shiny tracksuit for every day of the week.

And my parents wonder why I never married.

I slept with a copy of Joyce Brown’s Netball the Australian Way under my pillow, hoping it would stimulate dreams of netball greatness that would rub off on me.

All my hopes and aspirations were linked to the netball court - for one hour every Saturday, that rectangle was my place of worship.

Every game was part of the grand plan. Part of what I thought was my destiny to represent the real green and gold.

“You’re gonna play for Australia, Angie”, my brother would say.

“I know”.

If I had to describe the look I’d say “Karate Kid in a pleated skirt”.

I was nine and I was invincible.

Many years later under the sandstone arches of the University of Adelaide, I discovered my other religion - feminism.

My eyes were opened to the power imbalance between women and men, and the ongoing fight for equal rights, opportunities and respect.

I found my voice and started using it for things that really mattered: Reclaim The Night marches through the streets of Adelaide, speaking out against violence; energetically arguing against sexism, double standards and inequality.

It didn’t feel all that radical back then; it just felt right.

How could women not want equality, equal pay and opportunities, control over their own bodies, better work conditions, better access to childcare, a world without rape and sexual harassment, and the right to feel safe inside and outside of their homes?

By the time I left uni, I felt empowered.

I wasn’t going to put up with sexism and double standards.

I would call out inequality and misogyny at every opportunity, and make the world a better place.

Then I landed in sport.

Where you can experience sexism, double standards, inequality and misogyny all before lunchtime.

It was 1997 - and some sports weren’t even aware of the existence of women.

As I say in my book - Breaking The Mould, Taking a Hammer to Sexism and Sport - if sport were a cake, the filling would be chest hair.

I knew I was entering a male-dominated profession.

In the sporting “Game of Thrones” men hold sovereign power; they make the rules and call the shots.

Over the years, my love of sport has been severely tested, and on more than one occasion I’ve felt like walking away.

But I never did.

And I’m glad I stuck around because things are changing.

I’ve spent 20 years of my life observing the Australian sporting landscape as a sports journalist, presenter and now documentary-maker.

That’s 20 years of seeing women athletes undervalued, underpaid and ignored.

20 years of watching girls drop out of sport because there isn’t a pathway.

20 years of invisible female role models.

20 years of news editors telling me that no one cares about women’s sport.

20 years of watching men with mediocre talent get all the good jobs. That’s personal.

20 years of not always feeling like I belong.

But the Australian sporting landscape is changing.

The past three years have changed the conversation about women and sport.

No longer is the word ‘equality’ an afterthought.

Equality has become central to the whole discussion.

Where it belongs.

Until now, it’s always been about the business case for change – the men in charge of sport have argued the business case for including women - when it should be the starting point.

In my book, I argue the moral case for equality and diversity is more compelling than the business case.

Girls deserve the same opportunities and pathways as boys in sport. That should be our starting point.

So after 20 years, I can finally say the future is bright.

Clearer pathways are opening up for girls in sport - in a range of sports.

Female sporting role models are more visible.

Cricket, netball and the footy codes are creating a more competitive landscape for women and pushing all sports to do more for girls and women - facilities, pay, conditions, sponsorship, respect and recognition.

It’s no longer good enough to say “we want to be the sport of choice for girls and women” and do nothing - these sports actually have to do something.

And if they don’t understand this is now a matter of equality they’re going to be left behind.

The train has well and truly left the station.

I will briefly mention AFL Women’s here.

I don’t think I’ve ever been brief about AFLW but I will try - it’s my favourite topic.

AFLW is the most important thing to happen in sport in my lifetime.

Why?

Australian football is our indigenous game, our national game. It’s in our blood.

For a hundred years, writers, playwrights, filmmakers, poets and artists have depicted men in football – the embattled coaches, presidents, CEO’s, committeemen and the under-performing gun recruit – much-loved storylines that have shaped our sporting and cultural identity.

Alan Hopgood, David Williamson, Bruce Dawe, Martin Flanagan – men telling stories about men.

Women have been excluded on and off the field, despite having a deep love for the game.

A lot of us grew up kicking the footy in the street, the backyard and the local park - in my own little world boys existed for the sole purpose of kick to kick.

(I sometimes think I should have stuck to that general rule).

The path to the AFLW has been a long one. Its players are, in many ways, modern day suffragists - brave women who stared down convention and won.

Debbie Lee, Peta Searle, Lisa Hardeman and others, who fought for respect and a national competition long before it was fashionable to do so, were mocked, ridiculed and abused for fighting for equal rights.

It’s because of these brave women we now have an elite national competition – (you know that thing that men have had for ages?).

The AFLW Movement (and it is a movement) is changing society.

It sends the message to women and girls that it’s ok to play this game. It’s ok to be physical.

It says don’t get drawn into the feminine stereotype that’s been constructed for you - you can create your own version of what it means to be feminine, what it means to be a girl.

Sport is changing for the better.

We’re finally looking at both men and women and celebrating their differences.

Women’s sport is physically different to men’s but that doesn’t make it any less strategic or passionate – in fact, you could argue relying less on brute force puts more of an emphasis on tactics and strategy making it more of a spectacle.

We’re seeing less sexploitation of women athletes. This practice still goes on but it’s not as common as it was back in the old Matildas nude calendar days.

And casual sexism is being called out and this is really important because we know there’s a link between casual sexism, which demeans women, and the sorts of attitudes that give rise to violence against women.

But please don't think for a moment we’ve made it.

Despite the advances there’s still a way to go.

Women athletes are still striving for equal pay, they still don’t have access to the same opportunities and resources as their male counterparts. A sportswoman’s worth is still based on her attractiveness or sex appeal, sexist ‘jokes’ and ‘throwaway lines’ are still part of the landscape and women continue to be underrepresented in positions of power, including the media.

So how can the new sporting landscape help end violence against women?

Firstly, sport is our national obsession.

Sport is accessible - it reaches boys, men, girls and women.

And sport is at its best when it’s connected to something much bigger.

This is why it can drive positive change in attitudes and behaviours.

There is a huge body of respected research to show that gender inequality drives violence against women. That disrespect towards women and rigid gender stereotypes are key drivers of this unacceptable violence.

Sport is starting to understand the link between sexism and violence against women, and its using its power and influence to change the story.

Prevention work is about far more than simply raising awareness and putting one woman in the board room or on a sports panel show.

It’s about changing culture, changing the rules by which we play, and changing the environments we operate in.

It’s about working hard to ensure a level playing field is a reality for players, staff members, volunteers, fans and anyone connected to the clubs.

It’s about extending the principles of equality and fairness beyond the field into the boardroom, the coach’s box, the stands, the change rooms, and the media.

It’s about sporting organisations setting the standard of zero tolerance for sexism, discrimination and violence against women.

For sports leaders and role models, it’s about stamping out sexism and inequality – setting the tone, and the example, for others to follow.

It’s about creating inclusive, equitable, healthy and safe environments for men and women, boys and girls.

I can’t tell you how excited I was when I heard AFLW players speak out against the crappy idea of a 6-week regular season next year. As someone who watches cultural change in sport closely this was a significant shift. The players have found their voice, just as the mighty Matildas did in 2015 when they demanded better pay and respect.

Or how excited I was when Richmond superstar Jack Riewoldt sat on stage at the season launch and spoke about re-defining masculinity. We would never have heard that 20, 10, 5 or even two years ago.

Or how excited I was when jockey Michelle Payne told the doubters to get stuffed.

This is cultural change.

Women in sport can’t just sit back and wait for things to happen organically… because we know how that plays out for women.

Organic is good when it comes to fruit and vegetables… but when it comes to social change, organic doesn’t cut it.

We need action.

We need intervention.

We need acts of courage.

We need leadership.

It’s not the job of sport alone to end violence against women.

But sport provides a platform to promote women’s participation and opportunities, challenge gender stereotypes and roles and encourage respectful and equal relationships.

It has to be a team effort, and if we all work together, sport can help change the story that ends in violence against women.

Rest assured, I will keep going.

I’m feeling invincible again.

Thank you

To purchase Ang’s book, ‘Breaking the Mould’.

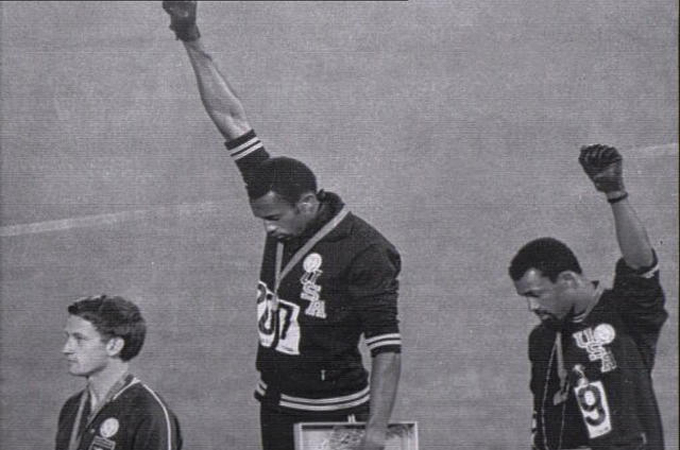

for Peter Norman: 'In the words of John Carlos, 'tell your children about Peter Norman' AOC Order of Merit Acceptance, by Janita Norman - 2018

My name is Janita Norman, I am Peter's eldest daughter. I am honoured to represent my family this evening. Attending tonight are Peter’s children Sandra Kadri, Gary, Belinda and Emma Norman, his 6 grandchildren, sister Elaine, her husband Michael, nephew John. Thelma Norman Peter's mother, my mum Ruth and Belinda and Emma’s mum Jan. I thank the AOC for hosting a wonderful celebration of Dad’s achievements tonight.

My brother and sisters assure me that being the family spokesperson is one of the responsibilities of the eldest child and at risk of revealing my age, their claim that I was the only child born prior to the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games further justifies to them ...my taking on this task tonight.

We are delighted at the AOC’s decision to honour Peter.... the announcement caused much excitement within our family, both smiles and tears – it evoked many emotions. About time?? Or Timed to perfection - What a great thing to happen this year, the 50th anniversary of the Mexico Olympic Games. A year of celebration, of recognition and of reflection of Dad’s life and his achievements.

It is sad that Peter is not here to receive the award, we know that he would be incredibly proud, humbled and ‘chuffed’ for the recognition bestowed upon him by the Australian Olympic Committee. He was often uncomfortable with recognition but I think in his own cool and calm way – even he would have struggled to conceal his elation at being recognised as one of our country’s great athletes.

We thank the AOC for recognising and acknowledging Peter's sporting achievements, his ongoing contribution to sport and for acknowledging the stand he made in support of his fellow athletes on the victory dais in 1968. His sporting career which encompassed Australian championships, Representing Australia at Empire, Pan Pacific and Commonwealth Games, the Olympic silver medal and the long standing Australian 200metres record. Fifty years holding the Australian record is in itself worthy of celebration.

In the past there has been conjecture over Peters place within his own sporting community, the award is recognition for a great athlete, and for a humanitarian and sends a clear message that Peter is accepted and recognised as he should be.

It is difficult to imagine any of these important achievements in isolation as it is a combination of all these things that have combined to make Peter Norman the unique story that is.

What if he had just run the race, won the medal and not been involved anything controversial – surely that would have been easier?

The race..... that incredible race, I have seen it countless times and I still hold my breath from that moment where there is that explosion of power on the home straight, as I lean forward toward the finish line, hold my breath ..... and then YES!!!

I have heard it said many times that his stand cast a shadow over what should have been a moment of sporting glory - an Olympic silver medal, an amazing athletic performance finishing second to split the two incredibly strong, formidable columns of pure power – Tommie Smith & John Carlos

As a child, with no understanding of the issues or the bigger picture, I was unsure if my father was a Hero or if he had done something to be ashamed of … a view that has now been replaced with understanding and admiration for standing up for his belief that “every man is born equal”

What I was sure about, was that Peter Norman landed on the world stage and in many ways became public property. The moment in time that he changed from being Dad, husband, son, brother....to part of history, that moment in time that is so familiar to us, captured forever in that iconic image.

I recall ---- Talking to an interested person a few years ago about the 68 Olympics-----I mentioned that my father won a silver medal in the 200metres -----I said “I’m sure you know the image, the one with the two African American athletes stand together with the little known Australian athlete – on the victory dais receiving their medals – taking a stand for civil rights – to which they said.............. - OMG -----I know that image---- That is incredible---so which one is your dad???

Interesting-----

So - Why Peter Norman?

Throughout Peter's life he touched many people personally or by identification with his story. He had an incredible sporting ability and the ability to motivate and inspire others.

You couldn’t help but like Peter, he was charismatic – He believed in people and people believed in him. He made lasting impressions on people. Over the years I have had countless people say to me..... .I met your father........... he was amazing................. .and they would share their story.

He was passionate about sport and athletics and hoped for the day that his record would be broken as this would be a demonstration of the competitive spirit, which he valued highly.

During his life he mentored young athletes and continues to inspire Australian sprinters who challenge themselves to better Peter’s record times and achievements. He often addressed groups of students, not to talk about his own achievements but to inspire and encourage, to talk about doing your absolute best, challenging yourself and being persistent.

Dad was generous with his time in many sporting areas, presenting medals, encouraging young kids, assisting with the Tri State games. He valued people’s sporting endeavours at any level with any ability.

It is not only in the sporting realm that Dad is held in high regard, Peter Norman is known as a Humanitarian, embraced by communities, groups and individuals who aspire to uphold the values for which he stood. He wasn't a political activist, he was clear and steadfast in his belief.

Primary and secondary school students study Social justice and Human rights as part of their course of studies. In a country that holds its sports men and women in high esteem Dad’s sporting achievements coupled with his courageous stand provide the perfect platform from which to convey the important message of acceptance, equality and inclusion to our children.

This is not a story that hides in history. This is a story that has its own life force, one which is constantly evolving and is as relevant today as it was 50 years ago, a story that is strengthening with added meaning over time and not diminishing.

A story that did not end in 2006 with Dad’s passing, since then it has gathered momentum as our society in many ways is more aware and ready to embrace the values of equality, inclusion and fundamental human rights.

For our family, it is important that Peter’s legacy continues, that Peter Norman is known as an important Australian sportsman and that his message resonates with each up and coming generation.

In the words of John Carlos ...... 'tell your children about Peter Norman'

Last year I received a message from a 12 year old student from the Bahamas. Beau was preparing his final important school assignment in preparation for his junior school graduation. His presentation was titled “Racism in Sport”

His message was so simple and so powerful, it moved our family to tears

His message read:

“My teacher (Ms Waterhouse) and I have been very touched by the story of your father and his courage during the 1968 Olympics. I know he is no longer alive but I still want to say THANK YOU to him for doing something so brave.”

This is Beau with his friends...........

Dad would have been overwhelmed by Beau’s message and this wonderful image, as we were.

Beau received a standing ovation, when he presented his project, spoke about Peter Norman and mentioned that he had reached out to Peter’s family.

This is the reason the story continues, this is why we need to recognise Peter Norman and why it is important to share the story with future generations

The Order of Merit is an important part of the progression of Dad’s story. Powerful and meaningful recognition by the Australian Olympic Committee that they value the sporing achievement of Peter Norman, his long standing Australian record and also the impact that his stand of support has made and continues to make to our society.

On behalf our family we are honoured to receive the Order on behalf of Peter.

Thank you

Jerry Kramer: 'You can if you will', Pro Football Hall of Fame - 2018

4 August 2018, Canton, Ohio, USA

We’ve got to go back to Sand Point High for just a minute. Wonderful town, wonderful times. Small town – 3,000 people, big lake. We had a great football team. This clumsy ox, a sophomore, showed up for practice one fall. I had grown about a foot and I couldn’t walk and chew gum at the time. I was just a mess. I wanted to be a fullback. I didn’t want to be a lineman. I wanted to be a fullback. My coach says, ‘Well, Jerry, that’s wonderful. If you want to be a fullback, you’ll sit on the bench. But if you want to be a tackle, you’ll probably start.’

Oh, boy, I don’t want to sit on the bench. I think I’d rather start.’ So, I started but I wasn’t all that excited about playing in the line. We had a line coach, an older fellow named Dusty Klein, that came up one day and knew who I was and knew that I was struggling. He grabbed my hand and looked at my hand and said, ‘Son, you’ve got big hands, you’ve got big feet. One of these days, you’re going to grow into them. He said, you’re going to be a hell of a player one of these days.’ I looked at him and I was curious and a little amazed, a little amused, a little bit of everything and looked me in the eye and said, ‘You can if you will.’ He started to walk away and I said, ‘Can what?’ He said, ‘You can if you will.’ And he walked away and left me to think about that.

...

The feeling of team is a wonderful thing. It’s the thing that I think most of us play for is because there’s a team and we want to be part of the team. I got drafted in the fourth round by the Green Bay Packers. My classmate, Wayne Walker, who played with Detroit for 15 years, was waiting for me when I came out of class. He said, ‘You got drafted!’

I said, “‘Great, what round was I?’”

“‘Fourth round.’”

“‘Wonderful.’”

“’Who drafted me?’”

“‘Green Bay.’”

“‘Green Bay? Where the hell is Green Bay?’”

“We honestly got a map. ‘Oh, it’s way back there by Chicago. Oh, it’s by a big lake. Oh, that is a big lake.'

...

We were having a wonderful time playing football in Green Bay. We were professional football players and we were making a few bucks and life was good. Our record wasn’t so hot. We were 1-10-1 (in 1958) and had the worst record in the history of the Green Bay Packer organization. We played the Baltimore Colts one Sunday afternoon. They beat us 56-0. They had a white colt that ran around the field every time they scored. We damn near killed him.

...

We went onto Green Bay. I went to the Shrine Game and had a big contract negotiation. I’m sure these young guys would be excited by the numbers and the whole process. We’re playing in the Shrine Game and the general manager for the Packers calls me over and says, ‘We’d like to talk contract with you.’ We didn’t have agents, we didn’t have any information that was printed, we didn’t have any idea what the guys were making. I go to my college coach, I said, ‘What kind of money should I ask for?’ He said, ‘Jerry, if you can get $7,000, you’ll be doing really good.’ So, I went to San Francisco and went in to negotiate with the guys and my general manager said, ‘Jerry, we’d like to sign you to a contract. What are you thinking about?’ I said, ‘$8,000.’ (He said) ‘OK, sign here.’ So, I left a few bucks on the table. But then I recovered quickly. I said, ‘I want a signing bonus, too.’ He said, ‘What about $250.’ (I said) ‘That’d be great. That’d be super.’ I get to Green Bay and we get our first game check after the preseason and there’s a $250 deduction from my check. I go to the general manager and he says, ‘Jerry, that was an advance. That wasn’t a bonus.’ So, I didn’t get a bonus.

...

Coach Lombardi arrived and the world turned around. First of all, he came in and said, ‘I’ve never been a loser and I’m not about to start now. If you’re not willing to make the sacrifice, to pay the price, to do the things that you have to do to win, then get the hell out!’ We kind of looked at him and said, ‘Can’t be that bad.’ He said, ‘We’re going to work harder than you’ve ever worked in your life. There’s only three things in your life: your God, your family and the Green Bay Packers.’”

...

He worked us harder than we had ever worked in our lives. We had guys losing consciousness every practice. Every exercise session, two, three guys would lose consciousness. One kid showered after practice, got on the bus, went back to the dormitory, got to the line in the chow hall and passed out. We were not real receptive to his philosophical comments but he would talk to us every night about principles that he believed in. He started with preparation – how you must be physically, mentally, emotionally prepared for the game. He would go on and on and on and we’d go, ‘Well, everybody’s got to be prepared. We’ll give you that. We’ll give you preparation. But that’s it!’ Then he would talk about commitment – mind, body, heart, soul and most of all self. ‘Well, maybe. You’ve got to be committed if you’re going to do something. If you’re really going to be involved, you might as well be committed. So, I’ll give him commitment, too.’ And discipline. ‘You don’t do things right once in a while, you do them right all the time.’ So, we got into discipline, consistency, pride, tenacity, belief in your team and believe in yourself. It was an incredible experience to be with him.

...

He could be both very, very harsh and very, very gentle. We’re working awfully hard and I’m having a bad day. We’re all having a bad day on offense. We’re on the 1-yard line and we’re scrimmaging the defense and we’re about 30 to 40 minutes into practice and we’re getting stopped and we’re really having a difficult day. I missed a block and I come in for some attention. A little bit later, I jumped offside. The coach comes running across the field and he gets about 10 inches from my nose and he goes, ‘Mister, the concentration period for a college student’s about 5 minutes, high school’s about 3 minutes, kindergarten is 30 seconds! And you don’t have that? Where’s that put you?’ (Kramer hangs his head.) It put me checking my shoe shine. “Practice ended shortly after that and I go up to the locker room. He’s out with Bart (Starr) and the wide receivers for about 40 minutes longer and I’m sitting in front of my locker, took my hat and my shoulder pads off, looking at the carpet and wondering what I’m going to do with the rest of my life. I’m thinking about maybe another football team, maybe another job, maybe something else. I’m deep in thought and totally wrapped up in it and he comes in the door, sees me down at the far end of the locker room, comes down, pats me on the back of the neck, messes up my hair, slaps me on the shoulder. ‘Son, one of these days you’re going to be the best guard in football.’ A surge of energy entered my breath and filled me up. It was his approval and belief in me that he was passing on to me and it made a dramatic difference in my life. Approval and belief, Mom, Dad, approval and belief. Powerful, powerful tools. From that point on, I wanted to play a perfect football game. If he believed in me, I could believe in me. So, I tried to play a perfect game and we had a wonderful group of guys.

...

Just an incredible group of guys but we also had a wonderful team that believed in team, that played as a team and lived as a team and enjoyed one another as a team. My best example of that is the 1965 season. I had nine operations. I came back the next season and weighed 189 pounds at one point during the offseason. When I got done, I got up to 218 and I went into the coach’s office to talk contract with him. He said, ‘Jerry, go home. Just go home. I’ll pay your salary, take care of all of your hospital bills, take care of everything. Just go home.’

“‘Coach, I can’t go home. If I go home, I’ll never play again. I’ll miss the whole season, I’ll probably never play again.’”

“‘Well, I can’t count on you.’”

“‘I don’t care if you can count on me. I’m going to play.’”

“‘Jerry, I wish you’d just go home.’”

“‘No, I’m not going home.’”

“We did this for 45 minutes. Finally, he says, ‘OK, I’m going to put you with the defense.’ I said, ‘Great, I always wanted to play defense, anyway.’” So, I was (a little) cocky because I was getting on the field and I certainly wasn’t prepared for it. Months later, I’d take the field and I’m about 220. We had a tradition when we’d run three laps around the field. I ran a lap-and-a-half and my lungs seized up. I couldn’t breathe, I couldn’t get any air, I couldn’t do anything at all. Don Chandler, my teammate and kicker, came over to me and said, ‘What’s wrong, pal?’ I said, ‘I can’t breathe.’ He says, ‘How much did you run?’ I said, ‘a lap-and-a half,’ He said, ‘I’ll run the other lap-and-a-half.’

“He said, ‘You and I are going to sit together during calisthenics. You’re going to do whatever you can do. If you can only do five sit-ups and they do 50, I’ll do 45. I’m a kicker and I don’t have to do anything if I don’t want to and I don’t normally. If they do 50 push-ups and you can only do three, I’ll do 47. Between you and I, we’ll do what one of those guys does.’ So, Don Chandler set beside me for 35 days and he helped me every step of the way. At the end of 35 days, I could do the calisthenics. I weighed about 235 at that point and I could do all the exercises, so they put me back on offense and we won a title in ’65, we won one in ’66, we won one in ’67, my book was published in ’68, so a great part of my life followed that probably would never have been without Don Chandler.

...

I’ve got a couple thoughts from other voices that I’d love to share with you about accomplishments and approval and those kinds of things. There’s a poem called, ‘Invictus’ (by William Ernest Henley). If you’re go be an achiever, you’re going to be a doer, you’re going to make something out of yourself, there’s certain principles and certain qualities you need. At this point, it kind of reflects the thought process of an achiever. It goes something like:

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

...

There was a fellow by the name of William Jennings Bryan who was a warrior and a really brilliant man. He said, ‘Success in life is not so much a matter of chance as it is a matter of choice.’ We choose to do the right thing and we choose not to do the right thing. So a great deal in life is a matter of choice. Coach Lombardi, to sum it all up, after the game is over, the stadium lights are out, the parking lot’s empty, you’re back in the quiet of your room, championship ring is on the dresser, the only thing left at this time is for you to lead a life of quality and excellence and make this world a little bit better place because you were in it. You can if you will. You can if you will. Thank you.

Malcolm Blight: 'I couldn't give a rat's tossbg', Channel 10, post match blast - 2008

20 August 2008, Channel 10 Melbourne, Australia

Former president of St Kilda Rod Butterss, a friend of Blight knocker Grant Thomas, had gone on record as saying Blight had lost his zeal for coaching by the time he came to St Kilda in 2001.

I couldn't give a rat's tossbag whether he thought I could coach, or anybody thought I could coach.

Or could play.

I don't care. Have an opinion, we all have an opinion.

But when he talked about commitment, to St Kilda, for the time I was there, that's absolute garbage, made by a very naive person.

Say I couldn't coach, Stephen, say I made the wrong call. say I said something to the wrong, say I said something bad ... all I did was handle some egos, try to handle some egos in a very bad football club, that had won two games the year before.

Stephen Quartermaine: He said that you weren't good with the kids, that you were better with a mature list?

Blight: Oh yeah, so in Adelaide and Geelong, both very young teams, we came from nowhere to playing grand finals, with young teams! C'mon, that a wank!

Nelson Mandela: ‘Sport has the power to change the world’ Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award - 2000

25 May 2000, Monaco, France

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you

I am happy to be with you tonight at the first Laureus World Sports Award. Sport has the power to change the world. [applause] It has the power to inspire, it has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope, where once there was only despair. It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers. It laughs in the face of all types of discrimination.

The heroes standing with me are examples of this power. They are valiant not only in the playing field, but also in the community, both local and international. They are champions and they deserve the world’s recognition.

[Applause]

Together they represent an active, vigorous Hall of Fame. A Hall of Fame that goes out into the world, spreading help, inspiration and hope.

Their legacy will be an international community where the rules of the game are the same for everyone, and behaviour is guided by fair play and good sportsmanship. I ask you now to rise and join me in commending the original inductees into the World Sports Academy Hall of Fame.

[Applause]

It is now my great pleasure to present a very special Laureus award - the Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award - given to a world athlete who exemplifies the highest virtue of sport, honour, courage, joy and perseverance. Our first honouree is a man who is both an athlete for the ages and a beacon of hope for the millions.

He began life in poverty and rose to the highest level of fame. To watch him play was to watch the delight of a child combined with the extraordinary grace of a man in full.

Ladies and gentlemen

It is my honour to present the inaugural Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award to Edson Arantes do Nascimento or as he is known to world - Pele.

[Applause]

Pele is in Rome tonight to join with other world soccer stars in an international football match for peace.

[PELE]

Thank you very much Mr Mandela. It is a big honour to me to receive this award. And I want to thank also to World Sports Academy for this. Everybody knows I am in Roma. We are here for the peace in the world. Beautiful event, beautiful game. One more time - thank you Mr Mandela , thank you every body for that.

[PELE ends]

[Applause]

Congratulations to the great Pele. You are an enduring model for all athletes. In fact, for all of us, to admire and emulate. Thank you and good evening.

Martin Flanagan: 'Such extremes of poverty and wealth within one game', Norm Smith Oration - 2018

7 June 2018, Melbourne Cricket Club, MCG, Melbourne, Australia

If you drive through the Tasmanian midlands from Launceston to Hobart, as you pass through a clump of houses called Cleveland, you will see, on the left, Joe Pike’s paddock. This is where my father saw his first games of football as a child in the years immediately following World War 1. My grandfather, a railway ganger who could write no more than his name, was the backbone of the Cleveland Football Club. These were the years before electricity, before radio, and so my father’s earliest football memories were sitting around at night listening to his father and older brothers talk about the difficulty of getting a team because so many of the local lads had died at Gallipoli or on the Western Front. But when Cleveland got a team together, they played in Joe Pike’s paddock. So that’s where it starts for me, what I like to call my footy dreaming.

Cleveland had something else. It had the memory of a champion. George Challis was a mathematics teacher who played football on the wing and was renowned for his speed and accurate passing. Challis had been one of Tasmania’s best at the national carnival of 1911, and one of Carlton’s best in the 1915 grand final when they overcame Collingwood. Within 12 months, Sergeant George Challis was blown to pieces in France. Nothing whatsoever of him remained but a large gravestone stands in his memory in the small churchyard opposite Joe Pike’s paddock. What have I got from football? Memories, lots of them.