18 March 1992, National Press Club, Canberra, Australia

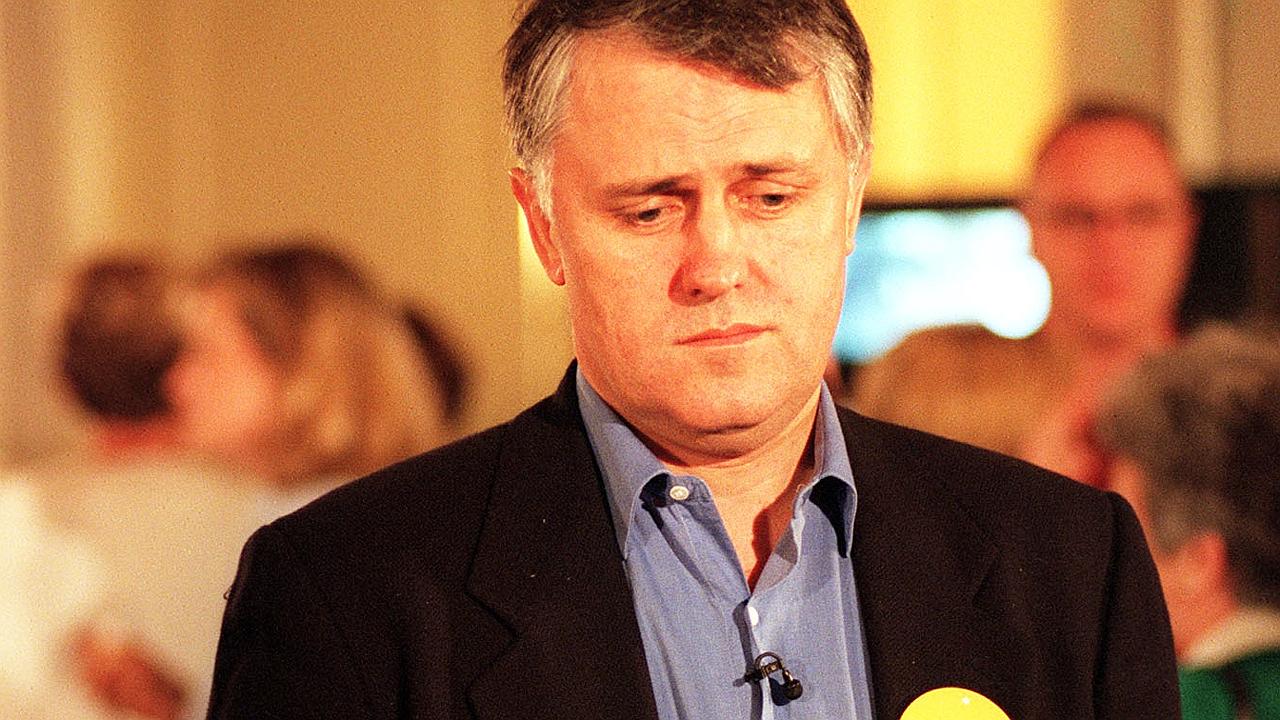

Malcom Turnbull is current Prime Minister of Australia. More information at Museum of Australian Democracy entry.

Listen to the speech. The questions afterwards are particularly interesting. When asked if he is still ambitious to be prime minister, Turnbull says, 'As far as my own political ambitions I have none. If nominated I will not stand, if elected I will not serve.' Twenty three years is a long time.

I will be blunt about my prejudices. I am an Australian. This is my native land, and I have no other. I believe that Australia's future and prosperity will be greatly advanced if our nation develops a stronger sense of patriotism and national purpose. We need to be prouder of ourselves. We need to love and respect our fellow countrymen much more than we do today, we need to rejoice in those things that make us different and we need to strive to make our nation foremost in every field of endeavor and enterprise.

For me, Australia comes first. I believe that our development as a more patriotic, more independent nation is being retarded by the fact that we have a foreigner as our head of state. We may have a Queen of Australia, but we do not have an Australian Queen. National sovereignty involves many facets, but among the most important is that a nation's constitutional and political structure is entirely indigenous. The leaders of a nation are appointed by, and are responsible to, the people and the institutions of that nation and no other.

It is no good monarchists pretending that the Queen is an Australian institution or that somehow or other her presence at the top of our constitutional pyramid is consistent with Australia's sovereignty as an independent nation. The historical truth is that the Queen is our head of state because in 1901, when our Constitution came into effect, Australia was no more than a self-governing colony within the British Empire. Our Constitution decrees that our Queen shall be Queen Victoria and her successors 'in the sovereignty of the United Kingdom'. That succession can be and has been, changed by the British parliament, but not by ours. If Prince Charles embraces Roman Catholicism he will not be able to succeed to the throne of our supposedly secular Commonwealth. If Britain becomes a republic, its first president will automatically become our head of state.

The Australian constitution gave extraordinarily wide powers to the Queen, wider than she wielded in the United Kingdom' The British government thereby reserved to itself the power to intervene in Australian affairs in much the same way a state Government in Australia can intervene and dismiss if necessary a local council.

When you see the word 'Queen' in our constitution, it is easy to construe it as meaning (in today's usage) the Queen of Australia acting on the advice of her Australian ministers. But in 1901 it meant the British Crown acting on the advice of its government in Whitehall. The

founding fathers of Federation had no aspirations to independence.

In the first three decades of this century the governor-general was first and foremost the representative of the British government in Australia. He was appointed by Whitehall and he was responsible to it. Indeed it was not until 1938 that Britain felt the need to appoint a high

commissioner to Australia. Until the Second World War Australia did not have any diplomatic representatives. It was a member of the League of Nations, but then so was India and no-one suggested it was independent. Australia did not even claim the right to declare war or peace.

War was declared by the King, for the Empire, and Australia followed the Empire in 1939 as much as it had in 1914.

In those days and for many decades to come, Australians were British subjects. They saw themselves as Britons living in Australia. They were an autonomous political sub-unit of the British Empire. If nation and nationhood require a belief in a separate and independent destiny, then Australia was not a nation. This may be regarded today as another symptom of Australia's confused sense of identity. I would not agree with that characterisation and latter-day Australian nationalists should be wary of vilifying their ancestors for lack of patriotism. Australia was, until relatively recent years, almost entirely composed of settlers from the British Isles. Even today, Australia has a higher percentage of white Caucasians than many parts of the United Kingdom itself. It was only natural that Australians, or people living in Australia, saw themselves as part of the same political unit from which they had spawned.

But, as the decades passed after Federation tensions increasingly developed in the relationship between Britain and its self-governing Dominions: Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, South Africa and the Irish Free State. Canada, South Africa and Ireland pressed hard for more autonomy and independence. Leaving Ireland aside as special case with a unique history, it can be seen that Canada and South Africa shared two distinct characteristics which Australia lacked. First their populations were not wholly British; large and influential sections of each had grave reservations about being associated with Britain at all. Second, because of their geography they did not perceive they faced a real threat of invasion. Australia on the other hand possessed an almost entirely British population. More importantly however it saw the Empire as the only possible source of defence in the event, some would have said the inevitable event, of an invasion from Japan.

So during the 1920s in the series of Imperial Conferences leading up to the 1931 Statute of Westminster we see Canada and South Africa forcing the pace of change while Australia (and New Zealand) dragged their heels. Australian politicians of that era, as different as William

Morris Hughes and Stanley Melbourne Bruce, rather favoured increased integration of the Empire. They wanted the Empire to speak with one voice, but they wanted that voice to be determined by a consultative process between the United Kingdom and the Dominions.

Again, it is easy to pick out speeches of all of our leaders from those days, Hughes, Scullin, Bruce, Lyons and even Curtin and point to examples of what today appear to be cringing subservience to Britain. [However] there is nothing shameful about these sentiments. Political

integration with Britain and its Empire was never a dishonourable course of action. Australian leaders were seeking a say in the Empire. At the 1943 federal conference of the Labor Party, Curtin described the full expression of our responsibilities in the post-war era to be 'a good

Australian, a good British subject and a good world citizen'. Or as the conservative politician and judge, Sir John Latham, observed in 1928, 'few Australians have the illusion that Australia could maintain her existence as a completely independent state. Alone Australia is weak . . .As a member of the British Commonwealth, Australia is strong.'

However noble ideas of Imperial Federation may have been, the truth was that the tide of history was running quite against it. Britain's idea of Empire was of one dominated by London, and that meant the British government of the day. Britain was nor prepared to share its

foreign policy with the Dominions and it preferred to have independent Dominions than have them meddling in what it saw as the concerns of Great Britain itself. To use a commercial metaphor, the imperial relationship was rather like that of a family company with grown up children. Some of the children want to move off and start their own businesses. others want to sit at the board table and jointly direct the enterprise. The patriarch however says: if you will not stay and do as you are told, then you had best leave.

So far from Australia seeking independence, quite the reverse is true. Australia increasingly undertook the responsibilities of nationhood because it had been turned out by its Mother Country. our nationhood was forced on us. We did not fight for it. Myth makers, particularly on the Left, will tell a different tale and I do nor mean to denigrate the Australian nationalism of our early radicals, many of them republicans, but it is well to remember they did not speak for the majority of Australians.

Given that background it is not surprising that a sense of national identity has been slow in coming. Right through the long reign of Sir Robert Menzies Australians were encouraged to believe they were still both British and Australian. It was conventional within the memory of

most of us to fly both the Union Jack and the Australian flag on public buildings. Our national anthem was 'God Save the Queen' until relatively recently. There was little emphasis in Australia on that important aspect of separateness and distinction which is crucial to a sense of nationalism. It is only since 1986 that an ultimate court of appeal ceased to be a tribunal of English judges, the Privy Council, sitting in London.

In the nine months since the launch of the Australian Republican Movement the republican debate has progressed considerably. It is now an important and lively subject of discussion. Major newspapers have editorialised in favour of the republic, the Australian Labor party has

placed a republican Australia firm1y in its national platform. opinion polls for the first time are showing a majority of Australians in favour of the republic.

But despite this, some conservatives fail to come to terms with the debate. The most common defence of the monarchy is a shoulder shrugging 'if it ain't broke, don't fix it' caveman conservatism. Consider for a moment where human progress would be if that approach had

been taken to art, literature, technology or politics? The truth is that all human progress has been based on the desire to make something which is better. Societies which have turned their back on social or political progress have invariably atrophied and collapsed. Another disappointing conservative response is that recently employed by the Leader of the Opposition [John Hewson] who dismisses the republican movement as a 'distraction from the economic issues of the recession'. Does he really believe that we are incapable of

debating anything other than economic issues, or that Australians are so intellectually deficient they can only concentrate on one issue at a time? The republican debate is too important to become the subject of conventional party political debate where a cause supported by the Government is automatically opposed by the Opposition. But for the benefit of Mr Hewson, I would pose this question: has the success of other nations been advanced, or retarded, by a strong sense of national identity and purpose? Has the economic miracle of Japan or Germany been assisted by their keen focus on national self-interest? Was the rise to greatness of the United States assisted by that country's intense patriotism and sense of national mission? I am not saying the republic will make you rich. But history suggests patriotism is good for business.

But of all the conservative reactions I have heard, the most depressing was that which fell from John Howard when I debated him recently for a television program. Mr Howard said the monarchy had given us 'decades of stability'. I was immediately reminded of Victor Daley's poem about Queen Victoria's sexagenary procession in London in 1897:

Sixty years she's reigned a-holding up the sky

And bringing round the seasons, hot and cold and wet and dry

And in all that time she's never done a deed deserving gaol,

So 1et.joybe1ls ring out madly and delirium prevail.

Oh, the poor will blessings pour on the Queen whom they adore

When she blinks with puffy eyes at them, they'll hunger never more.

The political stability of Australia is a tribute to the political stability of Australians, not the grace and favour of their iong-distance monarch. The same monarch reigned over Fiji and did not seem to faze Colonel Rabuka, ancl the Queen of Grenada was unable to prevent the United

States Marines imposing their idea of political stability on that country. John Howard's remark, which I am sure he now regrets, is a typical example of how too many of our leaders subconsciously underrate themselves and the people that elected them.

The republican debate is one of the most important confronting us today. Economic issues will come and go, and never be resolved (at least to everyone's satisfaction). But today we are building a nation and there is no worthier enterprise for any of us than that. I imagine there will

always be some who will resist the republic, but few of our critics suggest it is not inevitable.

The Prime Minister [Paul Keating] has not been slow to recognise the increasing popularity of this cause. Mr Hewson does himself, his party and the nation no good at all in not following suit. Conservatives who fear change to our constitutional system should stop hiding behind the royal petticoats, acknowledge the inevitability of a republic and constructively participate in the debate about the constitutional changes that are needed to effect it.

It is not just conservatives we need to persuade, of course. Some Australians find it hard to see how such a change could be important. If you believe we should have a head of state at all, if you believe that office is of importance, then it follows that the head of state should reinforce the values and interests of our nation above all others. Whatever the Queen may represent to Australians, she does not represent Australia. She does not represent this nation to its own citizens and to the world at large she unequivocally represents Great Britain.

The monarchists of bygone decades genuinely believed that Australia was part of Greater Britain and their patriotism was sincerely a British one. They did not pretend that Australia was, or ought to be, independent. Today's monarchists are more disingenuous. They claim to be, Australian patriots, they claim Australia is independent but at the same time cling to the last symbol of colonialism. The Australian republic will put Australia first, and in our hearts at least, Australia should have no other place.