3 October 1957, Brighton, United Kingdom

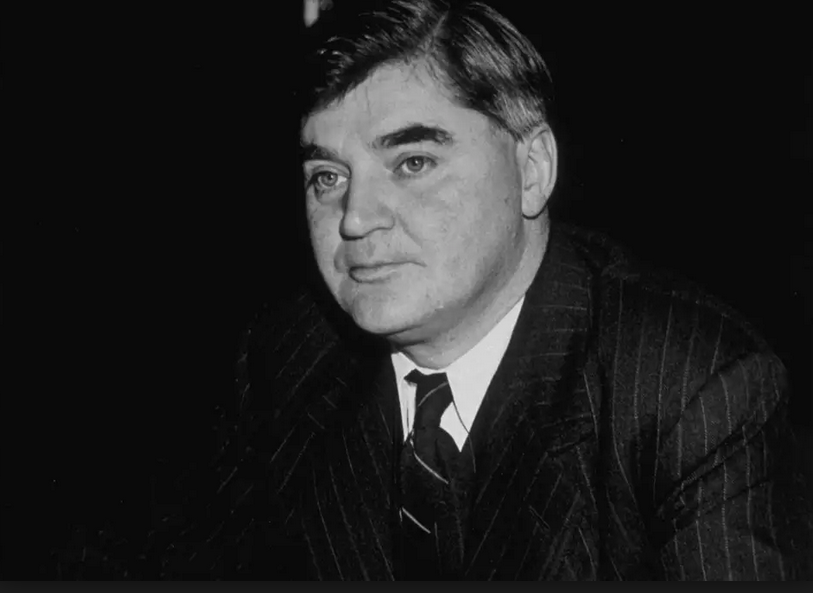

Aneurin (Nye) Bevan: 'There is only one hope for mankind - and that is Democratic Socialism', Resignation speech - 1951

23 April 1951, House of Commons, Westminster, London, UK

Mr. Speaker, it is one of the immemorial courtesies of the House of Commons that when a Minister has felt it necessary to resign his office, he is provided with an opportunity of stating his reasons to the House. These occasions are always exceedingly painful, especially to the individual concerned, because no Member ought to accept office in a Government without a full consciousness that he ought not to resign it for frivolous reasons. He must keep in mind that his association is based upon the assumption that everybody in Government accepts the full measure of responsibility for what it does.

The courtesy of being allowed to make a statement in the House of Commons is peculiarly agreeable to me this afternoon, because, up to now, I am the only person who has not been able to give any reasons why I proposed to take this step, although I notice that almost every single newspaper in Great Britain, including a large number of well-informed columnists, already know my reasons.

The House will recall that in the Defence debate I made one or two statements concerning the introduction of a Defence programme into our economy, and, with the permission of the House, I should like to quote from that speech which, I assumed at the time, received the general approval of the House. I said: “The fact of the matter is, as everybody knows, that the extent to which stockpiling has already taken place, the extent to which the 35 civil economy is being turned over to defence purposes in other parts of the world, is dragging prices up everywhere. Furthermore, may I remind the right hon. Gentleman that if we turn over the complicated machinery of modern industry to war preparation too quickly, or try to do it too quickly, we shall do so in a campaign of hate, in a campaign of hysteria, which may make it very difficult to control that machine when it has been created.” “It is all very well to speak about these things in airy terms, but we want to do two things. We want to organise our defence programme in this country in such a fashion as will keep the love of peace as vital as ever it was before. But we have seen in other places that a campaign for increased arms production is accompanied by a campaign of intolerance and hatred and witch-hunting. Therefore, we in this country are not at all anxious to imitate what has been done in other places. I would also like to direct the attention of the House to a statement made by the Prime Minister in placing before the House the accelerated armaments programme. He said: “The completion of the programme in full and in time is dependent upon an adequate supply of materials, components and machine tools. In particular, our plans for expanding capacity depend entirely upon the early provivision of machine tools, many of which can only be obtained from abroad. Those cautionary words were inserted deliberately in the statements on defence production because it was obvious to myself and to my colleagues in the Government that the accelerated programme was conditional upon a number of factors not immediately within our own control.

It has for some time been obvious to the Members of the Government and especially to the Ministers concerned in the production Departments that raw materials, machine tools and components are not forthcoming in sufficient quantity even for the earlier programme and that, therefore, the figures in the Budget for arms expenditure are based upon assumptions already invalidated. I want to make that quite clear to the House of Commons; the figures of expenditure on arms were already known to the Chancellor of the Exchequer to be unrealisable. The supply Departments have made it quite clear on several occasions that this is the case and, therefore, I begged over and over again that we should not put figures in the Budget on account of defence expenditure which would not be 36 realised, and if they tried to be realised would have the result of inflating prices in this country and all over the world.

It is now perfectly clear to any one who examines the matter objectively that the lurchings of the American economy, the extravagant and unpredictable behaviour of the production machine, the failure on the part of the American Government to inject the arms programme into the economy slowly enough, have already caused a vast inflation of prices all over the world, have disturbed the economy of the western world to such an extent that if it goes on more damage will be done by this unrestrained behaviour than by the behaviour of the nation the arms are intended to restrain.

This is a very important matter for Great Britain. We are entirely dependent upon other parts of the world for most of our raw materials. The President of the Board of Trade and the Minister of Supply in two recent statements to the House of Commons have called the attention of the House to the shortage of absolutely essential raw materials. It was only last Friday that the Minister of Supply pointed out in the gravest terms that we would not be able to carry out our programme unless we had molybdenum, zinc, sulphur, copper and a large number of other raw materials and non-ferrous metals which we can only obtain with the consent of the Americans and from other parts of the world.

I say therefore with the full solemnity of the seriousness of what I am saying, that the £4,700 million arms programme is already dead. It cannot be achieved without irreparable damage to the economy of Great Britain and the world, and that therefore the arms programme contained in the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s Budget is already invalidated and the figures based on the arms programme ought to be revised.

It is even more serious than that. The administration responsible for the American defence programme have already announced to the world that America proposes to provide her share of the arms programme not out of reductions in civil consumption, not out of economies in the American economy but out of increased production; and already plans are envisaged that before very long the American economy will be expanded for arms production by a percentage 37 equal to the total British consumption, civil and arms.

And when that happens the demands made upon the world’s precious raw materials will be such that the civilian economy of the Western world outside America will be undermined. We shall have mass unemployment. We have already got in Great Britain underemployment. Already there is short-time working in many important parts of industry and before the middle of the year, unless something serious can be done, we shall have unemployment in many of our important industrial centres. That cannot be cured by the Opposition. In fact the Opposition would make it worse—far worse.

The fact is that the western world has embarked upon a campaign of arms production upon a scale, so quickly, and of such an extent that the foundations of political liberty and Parliamentary democracy will not be able to sustain the shock. This is a very grave matter indeed. I have always said both in the House of Commons and in speeches in the country—and I think my ex-colleagues in the Government will at least give me credit for this—that the defence programme must always be consistent with the maintenance of the standard of life of the British people and the maintenance of the social services, and that as soon as it became clear we had engaged upon an arms programme inconsistent with those considerations, I could no longer remain a Member of the Government.

I therefore do beg the House and the country, and the world, to think before it is too late. It may be that on such an occasion as this the dramatic nature of a resignation might cause even some of our American friends to think before it is too late. It has always been clear that the weapons of the totalitarian States are, first, social and economic, and only next military; and if in attempting to meet the military effect of those totalitarian machines, the economies of the western world are disrupted and the standard of living is lowered or industrial disturbances are created, then Soviet Communism establishes a whole series of Trojan horses in every nation of the western economy.

It is, therefore, absolutely essential if we are to march forward properly, if 38 we are to mobilise our resources intelligently, that the military, social and political weapons must be taken together. It is clear from the Budget that the Chancellor of the Exchequer has abandoned any hope of restraining inflation. It is quite clear that for the rest of the year and for the beginning of next year, so far as we can see, the cost of living is going to rise precipitously. As the cost of living rises, the industrial workers of Great Britain will try to adjust themselves to the rising spiral of prices, and because they will do so by a series of individual trade union demands a hundred and one battles will be fought on the industrial field, and our political enemies will take advantage of each one. It is, therefore, impossible for us to proceed with this programme in this way.

I therefore beg my colleagues, as I have begged them before, to consider before they commit themselves to these great programmes. It is obvious from what the Chancellor of the Exchequer said in his Budget speech that we have no longer any hope of restraining inflation. The cost of living has already gone up by several points since the middle of last year, and it is going up again. Therefore, it is no use pretending that the Budget is just, merely because it gives a few shillings to old age pensioners, when rising prices immediately begin to take the few shillings away from them.

[HON. MEMBERS: “Hear, hear.”]

It is no use saying “Hear, hear” on the opposite side of the House. The Opposition have no remedy for this at all. But there is a remedy here on this side of the House if it is courageously applied, and the Budget does not courageously apply it. The Budget has run away from it. The Budget was hailed with pleasure in the City. It was a remarkable Budget. It united the City, satisfied the Opposition and disunited the Labour Party—all this because we have allowed ourselves to be dragged too far behind the wheels of American diplomacy.

This great nation has a message for the world which is distinct from that of America or that of the Soviet Union. Ever since 1945 we have been engaged in this country in the most remarkable piece of social reconstruction the world has ever seen. By the end of 1950 we had, as I said in my letter to the Prime Minister, assumed the moral leadership 39 of the world. [Interruption.] It is no use hon. Members opposite sneering, because when they come to the end of the road it will not be a sneer which will be upon their faces. There is only one hope for mankind, and that hope still remains in this little island. It is from here that we tell the world where to go and how to go there, but we must not follow behind the anarchy of American competitive capitalism which is unable to restrain itself at all, as is seen in the stockpiling that is now going on, and which denies to the economy of Great Britain even the means of carrying on our civil production. That is the first part of what I wanted to say.

It has never been in my mind that my quarrel with my colleagues was based only upon what they have done to the National Health Service. As they know, over and over again I have said that these figures of arms production are fantastically wrong, and that if we try to spend them we shall get less arms for more money. I have not had experience in the Ministry of Health for five years for nothing. I know what it is to put too large a programme upon too narrow a a base. We have to adjust our paper figures to physical realities, and that is what the Exchequer has not done.

May I be permitted, in passing, now that I enjoy comparative freedom, to give a word of advice to my colleagues in the Government? Take economic planning away from the Treasury. They know nothing about it. The great difficulty with the Treasury is that they think they move men about when they move pieces of paper about. It is what I have described over and over again as “whistle-blowing” planning. It has been perfectly obvious on several occasions that there are too many economists advising the Treasury, and now we have the added misfortune of having an economist in the Chancellor of the Exchequer himself.

I therefore seriously suggest to the Government that they should set up a production department and put the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the position where he ought to be now under modern planning, that is, with the function of making an annual statement of accounts. Then we should have some realism in the Budget. We should not be pushing out figures when the facts are going in the opposite direction.

40 I want to come for a short while, because I do not wish to try the patience of the House, to the narrower issue. The Chancellor of the Exchequer astonished me when he said that his Budget was coming to the rescue of the fixed income groups. Well, it has come to the rescue of the fixed income groups over 70 years of age, but not below. The fixed income groups in our modern social services are the victims of this kind of finance. Everybody possessing property gets richer. Property is appreciating all the time, and it is well known that there are large numbers of British citizens living normally out of the appreciated values of their own property. The fiscal measures of the Chancellor of the Exchequer do not touch them at all.

I listened to the Chancellor of the Exchequer with very great admiration. It was one of the cleverest Budget speeches I had ever heard in my life. There was a passage towards the end in which he said that he was now coming to a complicated and technical matter and that if Members wished to they could go to sleep. They did. Whilst they were sleeping he stole £100 million a year from the National Insurance Fund. Of course I know that in the same Budget speech the Chancellor of the Exchequer said that he had already taken account of it as savings. Of course he had, so that the re-armament of Great Britain is financed out of the contributions that the workers have paid into the Fund in order to protect themselves. [HON. MEMBERS: “Oh!”] Certainly, that is the meaning of it. It is no good my hon. Friends refusing to face these matters. If we look at the Chancellor’s speech we see that the Chancellor himself said that he had already taken account of the contributions into the Insurance Fund as savings. He said so, and he is right. [Interruption.] Do not deny that he is right. I am saying he is right. Do not quarrel with me when I agree with him.

The conclusion is as follows. At a time when there are still large untapped sources of wealth in Great Britain, a Socialist Chancellor of the Exchequer uses the Insurance Fund, contributed for the purpose of maintaining the social services, as his source of revenue, and I say that is not Socialist finance. Go to that source for revenue when no other source remains, but no one can say that 41 there are no other sources of revenue in Great Britain except the Insurance Fund.

I now come to the National Health Service side of the matter. Let me say to my hon. Friends on these benches: you have been saying in the last fortnight or three weeks that I have been quarrelling about a triviality—spectacles and dentures. You may call it a triviality. I remember the triviality that started an avalanche in 1931. I remember it very well, and perhaps my hon. Friends would not mind me recounting it. There was a trade union group meeting upstairs. I was a member of it and went along. My good friend, “Geordie” Buchanan, did not come along with me because he thought it was hopeless, and he proved to be a better prophet than I was. But I had more credulity in those days than I have got now. So I went along, and the first subject was an attack on the seasonal workers. That was the first order. I opposed it bitterly, and when I came out of the room my good old friend George Lansbury attacked me for attacking the order. I said, “George, you do not realise, this is the beginning of the end. Once you start this there is no logical stopping point.”

The Chancellor of the Exchequer in this year’s Budget proposes to reduce the Health expenditure by £13 million—only £13 million out of £4,000 million.[HON. MEMBERS: “£400 million.”] No, £4,000 million. He has taken £13 million out of the Budget total of £4,000 million. If he finds it necessary to mutilate, or begin to mutilate, the Health Services for £13 million out of £4,000 million, what will he do next year? Or are you next year going to take your stand on the upper denture? The lower half apparently does not matter, but the top half is sacrosanct. Is that right? If my hon. Friends are asked questions at meetings about what they will do next year, what will they say?

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is putting a financial ceiling on the Health Service. With rising prices the Health Service is squeezed between that artificial figure and rising prices. What is to be squeezed out next year? Is it the upper half? When that has been squeezed out and the same principle holds good, what do you squeeze out the year after? Prescriptions? Hospital charges? Where do you stop? I have been accused of 42 having agreed to a charge on prescriptions. That shows the danger of compromise. Because if it is pleaded against me that I agreed to the modification of the Health Service, then what will be pleaded against my right hon. Friends next year, and indeed what answer will they have if the vandals opposite come in? What answer? The Health Service will be like Lavinia—all the limbs cut off and eventually her tongue cut out, too.

I should like to ask my right hon. and hon. Friends, where are they going?[HON. MEMBERS: “Where are you going?”] Where am I going? I am where I always was. Those who live their lives in mountainous and rugged countries are always afraid of avalanches, and they know that avalanches start with the movement of a very small stone. First, the stone starts on a ridge between two valleys—one valley desolate and the other valley populous. The pebble starts, but nobody bothers about the pebble until it gains way, and soon the whole valley is overwhelmed. That is how the avalanche starts, that is the logic of the present situation, and that is the logic my right hon. and hon. Friends cannot escape. Why, therefore, has it been done in this way?

After all, the National Health Service was something of which we were all very proud, and even the Opposition were beginning to be proud of it. It only had to last a few more years to become a part of our traditions, and then the traditionalists would have claimed the credit for all of it. Why should we throw it away? In the Chancellor’s Speech there was not one word of commendation for the Health Service—not one word. What is responsible for that?

Why has the cut been made? He cannot say, with an overall surplus of over £220 million and a conventional surplus of £39 million, that he had to have the £13 million. That is the arithmetic of Bedlam. He cannot say that his arithmetic is so precise that he must have the £13 million, when last year the Treasury were £247 million out. Why? Has the A.M.A. succeeded in doing what the B.M.A. failed to do? What is the cause of it? Why has it been done?

I have also been accused—and I think I am entitled to answer it—that I had already agreed to a certain charge. I 43 speak to my right hon. Friends very frankly here. It seems to me sometimes that it is so difficult to make them see what lies ahead that you have to take them along by the hand and show them. The prescription charge I knew would never be made, because it was impracticable. [HON. MEMBERS: “Oh!”] Well, it was never made.

I will tell my hon. Friends something else, too. There was another policy—there was a proposed reduction of 25,000 on the housing programme, was there not? It was never made. It was necessary for me at that time to use what everybody always said were bad tactics upon my part—I had to manœuvre, and I did manœuvre and saved the 25,000 houses and the prescription charge. I say, therefore, to my right hon. and hon. Friends, there is no justification for taking this line at all. There is no justification in the arithmetic, there is less justification in the economics, and I beg my right hon. and hon. Friends to change their minds about it.

I say this, in conclusion. There is only one hope for mankind—and that is democratic Socialism. There is only one party in Great Britain which can do it—and that is the Labour Party. But I ask them carefully to consider how far they are polluting the stream. We have gone a long way—a very long way—against great difficulties. Do not let us change direction now. Let us make it clear, quite clear, to the rest of the world that we stand where we stood, that we are not going to allow ourselves to be diverted from our path by the exigencies of the immediate situation. We shall do what is necessary to defend ourselves—defend ourselves by arms, and not only with arms but with the spiritual resources of our people.

Aneurin (Nye) Bevan: 'It will place this country in the forefront of all countries of the world in medical services?' NHS Bill, second reading - 1946

30 April 1946. Westminster, United Kingdom

I beg to move that the Bill be now read a Second time.

In the last two years there has been such a clamour from sectional interests in the field of national health that we are in danger of forgetting why these proposals are brought forward at all. It is, therefore, very welcome to me – and I am quite certain to hon. Members in all parts of the House – that consideration should now be given, not to this or that sectional interest, but to the requirements of the British people as a whole. The scheme which anyone must draw up dealing with national health must necessarily be conditioned and limited by the evils it is intended to remove. Many of those who have drawn up paper plans for the health services appear to have followed the dictates of abstract principles, and not the concrete requirements of the actual situation as it exists. They drew up all sorts of tidy schemes on paper, which would be quite inoperable in practice.

The first reason why a health scheme of this sort is necessary at all is because it has been the firm conclusion of all parties that money ought not to be permitted to stand in the way of obtaining an efficient health service. Although it is true that the national health insurance system provides a general practitioner service and caters for something like 21 million of the population, the rest of the population have to pay whenever they desire the services of a doctor. It is cardinal to a proper health organisation that a person ought not to be financially deterred from seeking medical assistance at the earliest possible stage. It is one of the evils of having to buy medical advice that, in addition to the natural anxiety that may arise because people do not like to hear unpleasant things about themselves, and therefore tend to postpone consultation as long as possible, there is the financial anxiety caused by having to pay doctors’ bills. Therefore, the first evil that we must deal with is that which exists as a consequence of the fact that the whole thing is the wrong way round. A person ought to be able to receive medical and hospital help without being involved in financial anxiety.

In the second place, the national health insurance scheme does not provide for the self-employed, nor, of course, for the families of dependants. It depends on insurance qualification, and no matter how ill you are, if you cease to be insured you cease to have free doctoring. Furthermore, it gives no backing to the doctor in the form of specialist services. The doctor has to provide himself, he has to use his own discretion and his own personal connections, in order to obtain hospital treatment for his patients and in order to get them specialists, and in very many cases, of course – in an overwhelming number of cases – the services of a specialist are not available to poor people.

Not only is this the case, but our hospital organisation has grown up with no plan, with no system; it is unevenly distributed over the country and indeed it is one of the tragedies of the situation, that very often the best hospital facilities are available where they are least needed. In the older industrial districts of Great Britain hospital facilities are inadequate. Many of the hospitals are too small – very much too small. About 70 per cent. have less than 100 beds, and over 30 per cent. have less than 30. No one can possibly pretend that hospitals so small can provide general hospital treatment. There is a tendency in some quarters to defend the very small hospital on the ground of its localism and intimacy, and for other rather imponderable reasons of that sort, but everybody knows today that if a hospital is to be efficient it must provide a number of specialised services. Although I am not myself a devotee of bigness for bigness sake, I would rather be kept alive in the efficient if cold altruism of a large hospital than expire in a gush of warm sympathy in a small one.

In addition to these defects, the health of the people of Britain is not properly looked after in one or two other respects. The condition of the teeth of the people of Britain is a national reproach. As a consequence of dental treatment having to be bought, it has not been demanded on a scale to stimulate the creation of sufficient dentists, and in consequence there is a woeful shortage of dentists at the present time. Furthermore, about 25 per cent. of the people of Great Britain can obtain their spectacles and get their eyes tested and seen to by means of the assistance given by the approved societies, but the general mass of the people have not such facilities. Another of the evils from which this country suffers is the fact that sufficient attention has not been given to deafness, and hardly any attention has been given so far to the provision of cheap hearing aids and their proper maintenance. I hope to be able to make very shortly a welcome announcement on this question.

One added disability from which our health system suffers is the isolation of mental health from the rest of the health services. Although the present Bill does not rewrite the Lunacy Acts – we shall have to come to that later on – nevertheless, it does, for the first time, bring mental health into the general system of health services. It ought to be possible, and this should be one of the objectives of any civilised health service, for a person who feels mental distress, or who fears that he is liable to become unbalanced in any way to go to a general hospital to get advice and assistance, so that the condition may not develop into a more serious stage. All these disabilities our health system suffers from at the present time, and one of the first merits of this Bill is that it provides a universal health service without any insurance qualifications of any sort. It is available to the whole population, and not only is it available to the whole population freely, but it is intended, through the health service, to generalise the best health advice and treatment. It is intended that there shall be no limitation on the kind of assistance given – the general practitioner service, the specialist, the hospitals, eye treatment, spectacles, dental treatment, hearing facilities, all these are to be made available free.

There will be some limitations for a while, because we are short of many things. We have not enough dentists and it will therefore be necessary for us, in the meantime, to give priority treatment to certain classes – expectant and nursing mothers, children, school children in particular and later on we hope adolescents, Finally we trust that we shall be able to build up a dental service for the whole population. We are short of nurses and we are short, of course, of hospital accommodation, and so it will be some time before the Bill can fructify fully in effective universal service. Nevertheless, it is the object of the Bill, and of the scheme, to provide this as soon as possible, and to provide it universally.

Specialists will be available not only at institutions but for domiciliary visits when needed. Hon. Members in all parts of the House know from their own experience that very many people have suffered unnecessarily because the family has not had the financial resources to call in skilled people. The specialist services, therefore, will not only be available at the hospitals, but will be at the back of the general practitioner should he need them. The practical difficulties of carrying out all these principles and services are very great . When I approached this problem, I made up my mind that I was not going to permit any sectional or vested interests to stand in the way of providing this very valuable service for the British people.

There are, of course, three main instruments through which it is intended that the Health Bill should be worked. There are the hospitals; there are the general practitioners; and there are the health centres. The hospitals are in many ways the vertebrae of the health system, and I first examined what to do with the hospitals. The voluntary hospitals of Great Britain have done invaluable work. When hospitals could not be provided by any other means, they came along. The voluntary hospital system of this country has a long history of devotion and sacrifice behind it, and it would be a most frivolously minded man who would denigrate in any way the immense services the voluntary hospitals have rendered to this country. But they have been established often by the caprice of private charity. They bear no relationship to each other. Two hospitals close together often try to provide the same specialist services unnecessarily, while other areas have not that kind of specialist service at all. They are, as I said earlier, badly distributed throughout the country. It is unfortunate that often endowments are left to finance hospitals in those parts of the country where the well-to-do live while, in very many other of our industrial and rural districts there is inadequate hospital accommodation. These voluntary hospitals are, very many of them, far too small and, therefore, to leave them as independent units is quite impracticable.

Furthermore – I want to be quite frank with the House – I believe it is repugnant to a civilised community for hospitals to have to rely upon private charity. I believe we ought to have left hospital flag days behind. I have always felt a shudder of repulsion when I have seen nurses and sisters who ought to be at their work, and students who ought to be at their work, going about the streets collecting money for the hospitals. I do not believe there is an hon. Member of this House who approves that system. It is repugnant, and we must leave it behind – entirely. But the implications of doing this are very considerable.

I have been forming some estimates of what might happen to voluntary hospital finance when the all-in insurance contributions fall to be paid by the people of Great Britain, when the Bill is passed and becomes an Act, and they are entitled to free hospital services. The estimates I have go to show that between 80 per cent. and 90 per cent. of the revenues of the voluntary hospitals in these circumstances will be provided by public funds, by national or rate funds. And, of course, as the hon. Member reminds me, in very many parts of the country it is a travesty to call them voluntary hospitals. In the mining districts, in the textile districts, in the districts where there are heavy industries it is the industrial population who pay the weekly contributions for the maintenance of the hospitals. When I was a miner I used to find that situation, when I was on the hospital committee. We had an annual meeting and a cordial vote of thanks was moved and passed with great enthusiasm to the managing director of the colliery company for his generosity towards the hospital; and when I looked at the balance sheet, I saw that 97.5 per cent. of the revenues were provided by the miners’ own contributions; but nobody passed a vote of thanks to the miners.

I can assure the hon. and gallant Member that I was no more silent then than I am now. But, of course, it is a misuse of language to call these ‘Voluntary hospitals.” They are not maintained by legally enforced contributions; but, mainly, the workers pay for them because they know they will need the hospitals, and they are afraid of what they would have to pay if they did not provide them. So it is, I say, an impossible situation for the State to find something like 90 per cent of the revenues of these hospitals and still to call them “voluntary.’ So I decided, for this and other reasons, that the voluntary hospitals must be taken over.

I knew very well when I decided this that it would give rise to very considerable resentment in many quarters, but, quite frankly, I am not concerned about the voluntary hospitals’ authorities: I am concerned with the people whom the hospitals are supposed to serve. Every investigation which has been made into this problem has established that the proper hospital unit has to comprise about 1,000 beds – not in the same building but, nevertheless, the general and specialist hospital services can be provided only in a group of that size. This means that a number of hospitals have to be pooled, linked together, in order to provide a unit of that sort. This cannot be done effectively if each hospital is a separate, autonomous body. It is proposed that each of these groups should have a large general hospital, providing general hospital facilities and services, and that there should be a group round it of small feeder hospitals. Many of the cottage hospitals strive to give services that they are not able to give. It very often happens that a cottage hospital harbours ambitions to the hurt of the patients, because they strive to reach a status that they never can reach. In these circumstances, the welfare of the patients is sacrificed to the vaulting ambitions of those in charge of the hospital. If, therefore, these voluntary hospitals are to be grouped in this way, it is necessary that they should submit themselves to proper organisation, and that submission, in our experience, is impracticable if the hospitals, all of them, remain under separate management.

Now, this decision to take over the voluntary hospitals meant, that I then had to decide to whom to give them. Who was to be the receiver? So I turned to an examination of the local government hospital system. Many of the local authorities in Great Britain have never been able to exercise their hospital powers. They are too poor. They are too small. Furthermore, the local authorities of Great Britain inherited their hospitals from the Poor Law, and some of them are monstrous buildings, a cross between a workhouse and a barracks – or a prison. The local authorities are helpless in these matters. They have not been able to afford much money. Some local authorities are first-class. Some of the best hospitals in this country are local government hospitals. But, when I considered what to do with the voluntary hospitals when they had been taken over, and who was to receive them I had to reject the local government unit, because the local authority area is no more an effective gathering ground for the patients of the hospitals than the voluntary hospitals themselves. My hon. Friend said that some of them are too small, and some of them too large. London is an example of being too small and too large at the same time.

It is quite impossible, therefore, to hand over the voluntary hospitals to the local authorities. Furthermore – and this is an argument of the utmost importance – if it be our contract with the British people, if it be our intention that we should universalise the best, that we shall promise every citizen in this country the same standard of service, how can that be articulated through a rate-borne institution which means that the poor authority will not be able to carry out the same thing at all- It means that once more we shall be faced with all kinds of anomalies, just in those areas where hospital facilities are most needed, and in those very conditions where the mass of the poor people will be unable to find the finance to supply the hospitals. Therefore, for reasons which must be obvious – because the local authorities are too small, because their financial capacities are unevenly distributed – I decided that local authorities could not be effective hospital administration units. There are, of course, a large number of hospitals in addition to the general hospitals which the local authorities possess. Tuberculosis sanatoria, isolation hospitals, infirmaries of various kinds, rehabilitation, and all kinds of other hospitals are all necessary in a general hospital service. So I decided that the only thing to do was to create an entirely new hospital service, to take over the voluntary hospitals, and to take over the local government hospitals and to organise them as a single hospital service. If we are to carry out our obligation and to provide the people of Great Britain, no matter where they may be, with the same level of service, then the nation itself will have to carry the expenditure, and cannot put it upon the shoulders of any other authority.

A number of investigations have been made into this subject from time to time, and the conclusion has always been reached that the effective hospital unit should be associated with the medical school. If you grouped the hospitals in about 16 to 20 regions around the medical schools, you would then have within those regions the wide range of disease and disability which would provide the basis for your specialised hospital service. Furthermore, by grouping hospitals around the medical schools, we should be providing what is very badly wanted, and that is a means by which the general practitioners are kept in more intimate association with new medical thought and training. One of the disabilities, one of the shortcomings of our existing medical service, is the intellectual isolation of the general practitioners in many parts of the country. The general practitioner, quite often, practises in loneliness and does not come into sufficiently intimate association with his fellow craftsmen and has not the stimulus of that association, and in consequence of that the general practitioners have not got access to the new medical knowledge in a proper fashion. By this association of the general practitioner with the medical schools through the regional hospital organisation, it will be possible to refresh and replenish the fund of knowledge at the disposal of the general practitioner.

This has always been advised as the best solution of the difficulty. It has this great advantage to which I call the close attention of hon. Members. It means that the bodies carrying out the hospital services of the country are, at the same time, the planners of the hospital service. One of the defects of the other scheme is that the planning authority and executive authority are different. The result is that you get paper planning or bad execution. By making the regional board and regional organisation responsible both for the planning and the administration of the plans, we get a better result, and we get from time to time, adaptation of the plans by the persons accumulating the experience in the course of their administration. The other solutions to this problem which I have looked at all mean that you have an advisory body of planners in the background who are not able themselves to accumulate the experience necessary to make good planners. The regional hospital organisation is the authority with which the specialised services are to be associated, because, as I have explained, this specialised service can be made available for an area of that size, and cannot be made available over a small area.

When we come to an examination of this in Committee, I daresay there will be different points of view about the constitution of the regional boards. It is not intended that the regional boards should be conferences of persons representing different interests and different organisations. If we do that, the regional boards will not be able to achieve reasonable and efficient homogeneity. It is intended that they should be drawn from members of the profession, from the health authorities in the area, from the medical schools and from those who have long experience in voluntary hospital administration. While leaving ourselves open to take the best sort of .individuals on these hospital boards which we can find, we hope before very long to build up a high tradition of hospital administration in the boards themselves. Any system which made the boards conferences, any proposal which made the members delegates, would at once throw the hospital administration into chaos. Although I am perfectly prepared and shall be happy to cooperate with hon. Members in all parts of the House in discussing how the boards should be constituted, I hope I shall not be pressed to make these regional boards merely representative of different interests and different areas. The general hospital administration, therefore, centres in that way.

When we come to the general practitioners we are, of course, in an entirely different field. The proposal which I have made is that the ‘general practitioner shall not be in direct contract with the Ministry of Health, but in contract with new bodies. There exists in the medical ,profession a great resistance to coming under the authority of local government – a great resistance, with which I, to some extent, sympathise. There is a feeling in the medical profession that the general practitioner would be liable to come too much under the medical officer of health, who is the administrative doctor. This proposal does not put the doctor under the local authority; it puts the doctor in contract with an entirely new body – the local executive :council, coterminous with the local health area, county or county borough. On that executive council, the dentists, doctors and chemists will have half the representation. In fact, the whole scheme provides a greater degree of professional representation for the medical profession than any other scheme I have seen.

I have been criticised in some quarters for doing that. I will give the answer now: I have never believed that the demands of a democracy are necessarily satisfied merely by the opportunity of putting a cross against someone’s name every four or five years. I believe that democracy exists in the active participation in administration and policy. Therefore, I believe that it is a wise thing to give the doctors full participation in the administration of their own profession. They must of course, necessarily be subordinated to lay control – we do not want the opposite danger of syndicalism. Therefore, the communal interests must always be safeguarded in this administration. The doctors will be in contract with an executive body of this sort. One of the advantages of that proposal is that the doctors do not become – as some of them have so wildly stated – civil servants. Indeed, one of the advantages of the scheme is that it does not create an additional civil servant.

It imposes no constitutional disability upon any person whatsoever. Indeed, by taking the hospitals from the local authorities and putting them under the regional boards, large numbers of people will be enfranchised who are now disfranchised from participation in local government. So far from this being a huge bureaucracy with all the doctors little civil servants – the slaves of the Minister of Health, as I have seen it described – instead of that, the doctors are under contract with bodies which are not under the local authority, and which are, at the same time, ever open to their own influence and control.

One of the chief problems that I was up against in considering this scheme was the distribution of the general practitioner service throughout the country. The distribution, at the moment, is most uneven. In South Shields before the war there were 4,100 persons per doctor; in Bath 1,590; in Dartford nearly 3,000 and in Bromley 1,620; in Swindon 3,100; in Hastings under 1,200. That distribution of general practitioners throughout the country is most hurtful to the health of our people. It is entirely unfair, and, therefore, if the health services are to be carried out, there must be brought about a redistribution of the general practitioners throughout the country.

Indeed, I could amplify those figures a good deal, but I do not want to weary the House, as Ihave a great deal to say. It was, therefore, decided that there must be redistribution. One of the first consequences of that decision was the abolition of the sale and purchase of practices. If we are to get the doctors where we need them, we cannot possibly allow a new doctor to go in because he has bought somebody’s practice. Proper distribution kills by itself the sale and purchase of practices. I know that there is some opposition to this, and I will deal with that opposition. I have always regarded the sale and purchase of medical practices as an evil in itself. It is tantamount to the sate and purchase of patients. Indeed, every argument advanced about the value of the practice is itself an argument against freedom of choice, because the assumption underlying the high value of a practice is that the patient passes from the old doctor to the new. If they did not pass there would be no value in it. I would like, therefore, to point out to the medical profession that every time they argue for high compensation for the loss of the value of their practices, it is an argument against the free choice which they claim. However, the decision to bring about the proper distribution of general practitioners throughout the country meant that the value of the practices was destroyed. We had, therefore, to consider compensation.

I have never admitted the legal claim, but I admit at once that very real hardship would be inflicted upon doctors if there were no compensation. Many of these doctors look forward to the value of their practices for their retirement. Many of them have had to borrow money to buy practices and, therefore, it would, I think, be inhuman, and certainly most unjust, if no compensation were paid for the value of the practices destroyed. The sum of £66,000,000 is very large. In fact, I think that everyone will admit that the doctors are being treated very generously. However, it is not all loss, because if we had, in providing superannuation, given credit for back service, as we should have had to do, it would have cost £35 million. Furthermore, the compensation will fall to be paid to the dependants when the doctor dies, or when he retires, and so it is spread over a considerable number of years. This global sum has been arrived at by the actuaries and over the figure, I am afraid, we have not had very much control, because the actuaries have agreed it. But the profession itself will be asked to advise as to its distribution among the claimants, because we are interested in the global sum, and the profession, of course, is interested in the equitable distribution of the fund to the claimants.

The doctors claim that the proposals of the Bill amount to direction – not all the doctors say this but some of them do. There is no direction involved at all. When the Measure starts to operate, the doctors in a particular area will be able to enter the public service in that area. A doctor newly coming along would apply to the local executive council for permission to practise in a particular area. His application would then be re-referred to the Medical Practices Committee. The Medical Practices Committee, which is mainly a professional body, would have before it the question of whether there were sufficient general practitioners in that area. If there were enough, the committee would refuse to permit the appointment. No one can really argue that that is direction, because no profession should be allowed to enter the public service in a place where it is not needed. By that method of negative control over a number of years, we hope to bring about over the country a positive redistribution of the general practitioner service. It will not affect the existing situation, because doctors will be able to practise under the new service in the areas to which they belong, but a new doctor, as he comes on, will have to find his practice in a place inadequately served.

I cannot, at the moment, explain to the House what are going to be the rates of remuneration of doctors. The Spens Committee report is not fully available. I hope it will be out next week. I had hoped that it would be ready for this Debate, because this is an extremely important part of the subject, but I have not been able to get the full report. Therefore, it is not possible to deal with remuneration. However, it is possible to deal with some of the principles underlying the remuneration of general practitioners. Some of my hon. Friends on this side of the House are in favour of a full salaried service. I am not. I do not believe that the medical profession is ripe for it, and I cannot dispense with the principle that the payment of a doctor must in some degree be a reward for zeal, and there must be some degree of punishment for lack of it. Therefore, it is proposed that capitation should remain the main source from which a doctor will obtain his remuneration. But it is proposed that there shall be a basic salary and that for a number of very cogent reasons. One is that a young doctor entering practice for the first time needs to be kept alive while he is building up his lists. The present system by which a young man gets a load of debt around his neck in order to practise is an altogether evil one. The basic salary will take care of that.

Furthermore, the basic salary has the additional advantage of being something to which I can attach an increased amount to get doctors to go into unattractive areas. It may also – and here our position is not quite so definite – be the means of attaching additional remuneration for special courses and special acquirements. The basic salary, however, must not be too large otherwise it is a disguised form of capitation. Therefore, the main source at the moment through which a general practitioner will obtain his remuneration will be capitation. I have also made – and I quite frankly admit it to the House – a further concession which I know will be repugnant in some quarters. The doctor, the general practitioner and the specialist, will be able to obtain fees, but not from anyone who is on any of their own lists, nor will a doctor be able to obtain fees from persons on the lists of his partner, nor from those he has worked with in group practice, but I think it is impracticable to prevent him having any fees at all. To do so would be to create a black market. There ought to be nothing to prevent anyone having advice from another doctor other than his own. Hon. Members know what happens in this field sometimes. An individual hears that a particular doctor in some place is good at this, that or the other thing, and wants to go along for a consultation and pays a fee for it. If the other doctor is better than his own all he will need to do is to transfer to him and he gets him free. It would be unreasonable to keep the patient paying fees to a doctor whose services can be got free. So the amount of fee payment on the part of the general population will be quite small. Indeed, I confess at once if the amount of fee paying is great, the system will break down, because the whole purpose of this scheme is to provide free treatment with no fee paying at all. The same principle applies to the hospitals. If an individual wishes to consult, there is no reason why he should be stopped. As I have said, the fact that a person can transfer from one doctor to another ought to keep fee paying within reasonable proportions.

The same principle applies to the hospitals. Specialists in hospitals will be allowed to have fee-paying patients. I know this is criticised and I sympathise with some of the reasons for the criticism, but we are driven inevitably to this fact, that unless we permit some fee-paying patients in the public hospitals, there will be a rash of nursing homes all over the country. If people wish to pay for additional amenities, or something to which they attach value, like privacy in a single ward, we ought to aim at providing such facilities for everyone who wants them. But while we have inadequate hospital facilities, and while rebuilding is postponed it inevitably happens that some people will want to buy something more than the general health service is providing. If we do not permit fees in hospitals, we will lose many specialists from the public hospitals for they will go to nursing homes. I believe that nursing homes ought to be discouraged. They cannot provide general hospital facilities, and we want to keep our specialists attached to our hospitals and not send them into nursing homes. Behind this there is a principle of some importance. If the State owned a theatre it would not charge the same prices for the different seats. It is not entirely analogous, but it is an illustration. For example, in the dental service the same principle will prevail. The State will provide a certain standard of dentistry free, but if a person wants to have his teeth filled with gold, the State will not provide that.

The third instrument to which the health services are to be articulated is the health centre, to which we attach very great importance indeed. It has been described in some places as an experimental idea, but we want it to be more than that, because to the extent that general practitioners can operate through health centres in their own practice, to that extent will be raised the general standard of the medical profession as a whole. Furthermore, the general practitioner cannot afford the apparatus necessary for a proper diagnosis in his own surgery. This will be available at the health centre. The health centre may well be the maternity and child welfare clinic of the local authority also. The provision of the health centre is, therefore, imposed as a duty on the local authority. There has been criticism that this creates a trichotomy in the services. It is not a trichotomy at all. If you have complete unification it would bring you back to paper planning. You cannot get all services through the regional authority, because there are many immediate and personal services which the local authority can carry out better than anybody else. So, it is proposed to leave those personal services to the local authority, and some will be carried out at the health centre. The centres will vary; there will be larger centres at which there will be dental clinics, maternity and child welfare services, and general practitioners’ consultative facilities, and there will also be smaller centres – surgeries where practitioners can see their patients.

The health centres will be managed entirely by the health authorities. The health centre itself will be provided by the local health authority and facilities will be made available there to the general practitioner. The small ones are necessary, because some centres may be a considerable distance from people’s homes. So it will be necessary to have simpler ones, nearer their homes, fixed in a constellation with the larger ones.

The representatives on the local executives will be able to coordinate what is happening at the health centres. As I say, we regard these health centres as extremely valuable, and their creation will be encouraged in every possible way. Doctors will be encouraged to practise there, where they will have great facilities. It will, of course, be some time before these centres can be established everywhere, because of the absence of these facilities.

There you have the three main instruments through which it is proposed that the health services of the future should be articulated. There has been some criticism. Some have said that the preventive services should be under the same authority as the curative services. I wonder whether Members who advance that criticism really envisage the situation which will arise. What are the preventive services – Housing, water, sewerage, river pollution prevention, food inspection – are all these to be under a regional board? If so, a regional board of that sort would want the Albert Hall in which to meet. This, again, is paper planning. It is unification for unification’s sake. There must be a frontier at which the local joins the national health service. You can fix it here or there, but it must be fixed somewhere. It is said that there is some contradiction in the health scheme because some services are left to the local authority and the rest to the national scheme. Well, day is joined to night by twilight, but nobody has suggested that it is a contradiction in nature. The argument that this is a contradiction in health services is purely pedantic, and has no relation to the facts.

It is also suggested that because maternity and child welfare services come under the local authority, and gynaecological services come under the regional board, that will make for confusion. Why should it? Continuity between one and the other is maintained by the user. The hospital is there to be used. If there are difficulties in connection with birth, the gynaecologist at the hospital centre can look after them. All that happens is that the midwife will be in charge the mother will be examined properly, as she ought to be examined then, if difficulties are anticipated, she can have her child in hospital, where she can be properly looked after by the gynaecologist. When she recovers, and is a perfectly normal person, she can go to the maternity and child welfare centre for post-natal treatment. There is no confusion there. The confusion is in the minds of those who are criticising the proposal on the ground that there is a trichotomy in the services, between the local authority, the regional board and the health centre.

I apologise for detaining the House so long, but there are other matters to which I must make some reference. The two Amendments on the Order Paper rather astonish me. The hon. Member for Denbigh informs me, in his Amendment, that I have not sufficiently consulted the medical profession – I intend to read the Amendment to show how extravagant the hon. Member has been. He says that he and his friends are:

“unable to agree to a measure containing such far reaching proposals involving the entire population without any consultations having taken place between the Minister and the organisations and bodies representing those who will be responsible for carrying out its provisions…”

I have had prepared a list of conferences I have attended. I have met the medical profession, the dental profession, the pharmacists, nurses and midwives, voluntary hospitals, local authorities, eye services, medical aid services, herbalists, insurance committees, and various other organisations. I have had 20 conferences. The consultations have been very wide. In addition, my officials have had 13 conferences, so that altogether there have been 33 conferences with the different branches of the profession about the proposals. Can anybody argue that that is not adequate consultation? Of course, the real criticism is that I have not conducted negotiations. I am astonished that such a charge should lie in the mouth of any Member of the House. If there is one thing that will spell the death of the House of Commons it is for a Minister to negotiate Bills before they are presented to the House. I had no negotiations, because once you negotiate with outside bodies two things happen. They are made aware of the nature of the proposals before the House of Commons itself; and furthermore, the Minister puts himself into an impossible position, because, if he has agreed things with somebody outside he is bound to resist Amendments from Members in the House. Otherwise he does not play fair with them. I protested against this myself when I was a Private Member. I protested bitterly, and I am not prepared, strange though it may seem, to do something as a Minister which as a Private Member I thought was wrong. So there has not been negotiation, and there will not be negotiation, in this matter. The House of Commons is supreme, and the House of Commons must assert its supremacy, and not allow itself to be dictated to by anybody, no matter how powerful and how strong he may be.

These consultations have taken place over a very wide field, and, as a matter of fact, have produced quite a considerable amount of agreement. The opposition to the Bill is not as strong as it was thought it would be. On the contrary, there is very considerable support for this Measure among the doctors themselves. I myself have been rather aggrieved by some of the statements which have been made. They have misrepresented the proposals to a very large extent, but as these proposals become known to the medical profession, they will appreciate them, because nothing should please a good doctor more than to realise that, in future, neither he nor his patient will have any financial anxiety arising out of illness.

The leaders of the Opposition have on the Order Paper an Amendment which expresses indignation at the extent to which we are interfering with charitable foundations. The Amendment states that the Bill “gravely menaces all charitable foundations by diverting to purposes other than those intended by the donors the trust funds of the voluntary hospitals.”

I must say that when I read that Amendment I was amused. I have been looking up some precedents. I would like to say, in passing, that a great many of these endowments and foundations have been diversions from the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The main contributor was the Chancellor of the Exchequer. But I seem to remember that, in 1941, hon. Members opposite were very much vexed by what might happen to the public schools, and they came to the House and asked for the permission of the House to lay sacrilegious hands upon educational endowments centuries old. I remember protesting against it at the time – not, however, on the grounds of sacrilege. These endowments had been left to the public schools, many of them for the maintenance of the buildings, but hon. Members opposite, being concerned lest the war might affect their favourite schools, came to the House and allowed the diversion of money from that purpose to the payment of the salaries of the teachers and the masters. There have been other interferences with endowments. Wales has been one of the criminals. Disestablishment interfered with an enormous number of endowments. Scotland also is involved. Scotland has been behaving in a most sacrilegious manner; a whole lot of endowments have been waived by Scottish Acts. I could read out a large number of them, but I shall not do so.

Do hon. Members opposite suggest that the intelligent planning of the modern world must be prevented by the endowments of the dead? Are we to consider the dead more than the living? Are the patients of our hospitals to be sacrificed to a consideration of that sort?

We are not, in fact, diverting these endowments from charitable purposes. It would have been perfectly proper for the Chancellor of the Exchequer to have taken over these funds, because they were willed for hospital purposes, and he could use them for hospital purposes; but we are doing no such thing. The teaching hospitals will be left with all their liquid endowments and more power. We are not interfering with the teaching hospitals’ endowments. Academic medical education will be more free in the future than it has been in the past. Furthermore, something like £32 million belonging to the voluntary hospitals as a whole is not going to be taken from them. On the contrary, we are going to use it, and a very valuable thing it will be; we are going to use it as a shock absorber between the Treasury, the central Government, and the hospital administration. They will be given it as free money which they can spend over and above the funds provided by the State.

I welcome the opportunity of doing that, because I appreciate, as much as hon. Members in any part of the House, the absolute necessity for having an elastic, resilient service, subject to local influence as well as to central influence; and that can be accomplished by leaving this money in their hands. I shall be prepared to consider, when the Bill comes to be examined in more detail, whether any other relaxations are possible, but certainly, by leaving this money in the hands of the regional board, by allowing the regional board an annual budget and giving them freedom of movement inside that budget, by giving power to the regional board to distribute this money to the local management committees of the hospitals, by various devices of that sort, the hospitals will be responsible to local pressure and subject to local influence as well as to central direction.

I think that on those grounds the proposals can be defended. They cover a very wide field indeed, to a great deal of which I have not been able to make reference; but I should have thought it ought to have been a pride to hon. Members in all parts of the House that Great Britain is able to embark upon an ambitious scheme of this proportion. When it is carried out, it will place this country in the forefront of all countries of the world in medical services. I myself, if I may say a personal word, take very great pride and great pleasure in being able to introduce a Bill of this comprehensiveness and value. I believe it will lift the shadow from millions of homes. It will keep very many people alive who might otherwise be dead. It will relieve suffering. It will produce higher standards for the medical profession. It will be a great contribution towards the wellbeing of the common people of Great Britain. For that reason, and for the other reasons I have mentioned, I hope hon. Members will give the Bill a Second Reading.

Aneurin (Nye) Bevan: 'Get out! Get out! Get out!', Suez Crisis, Trafalgar Square speech - 1956

4 November 1956, Trafalgar Square, London.

It is a sad sad sad story that is unfolding itself before our eyes at the present time. I very very sad one indeed. I myself feel despondent, really despondent, about the situation into which we have been got. When some young Tory’s say, ‘oh, we are giving the lead,’ the lead to where!

Yes, the lead back to chaos, back to anarchy, and back to universal destruction.

That’s not the lead we want.

This policy of the British government is a policy of bankruptcy and despair. It’s not the policy of civilisation.

They’re hoping that the military situation in Egypt will soon resolve itself, and that we will be ‘militarily successful ‘. If we are successful, what will that prove? It will only prove that we are stronger than the Egyptians. It won’t prove that weare right. It’s only the logic of the bully, many Tory newspapers are saying today, ‘oh well, perhaps we are judging too soon?’ ‘It may be that (PM) Eden will get it all over with, and then we can breathe a sigh of relief.’

That’s what the Germans said about Hitler! They said, ‘he may be a liar, but will he be a successful liar? They said, he’s a bully, but will he be a successful bully? They were perfectly prepared to accept his morality, so long as he gives them the prizes.

But yeah, we must look further into this.

We are stronger than Egypt but there are other countries stronger than us. Are we prepared to accept for ourselves the logic we are applying to Egypt? If nations more powerful than ourselves accept the absence of principle, the anarchistic attitude of Eden and launch bombs on London, what answer have we got, what complaint have we got? If we are going to appeal to force, if force is to be the arbiter to which we appeal, it would at least make common sense to try to make sure beforehand that we have got it, even if you accept that abysmal logic, that decadent point of view.

We are in fact in the position today of having appealed to force in the case of a small nation, where if it is appealed to against us it will result in the destruction of Great Britain, not only as a nation, but as an island containing living men and women. Therefore I say to Anthony, I say to the British government, there is no count at all upon which they can be defended.

They have besmirched the name of Britain. They have made us ashamed of the things of which formerly we were proud. They have offended against every principle of decency and there is only way in which they can even begin to restore their tarnished reputation and that is to get out! Get out! Get out!

Aneurin (Nye) Bevan: 'The social furniture of modern society is so complicated and fragile that it cannot support the jackboot.'', Suez Crisis - 1956

5 December 1956, House of Commons, United Kingdom

The speech to which we have just listened is the last of a long succession that the right hon. Gentleman the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs has made to the House in the last few months and, if I may be allowed to say so, I congratulate him upon having survived so far. He appears to be in possession of vigorous health, which is obviously not enjoyed by all his colleagues, and he appears also to be exempted from those Freudian lapses which have distinguished the speeches of the Lord Privy Seal, and therefore he has survived so far with complete vigour.

However, I am bound to say that the speech by the right hon. Gentleman today carries the least conviction of all.

I have been looking through the various objectives and reasons that the Government have given to the House of Commons for making war on Egypt, and it really is desirable that when a nation makes war upon another nation it should be quite clear why it does so. It should not keep changing the reasons as time goes on.

There is, in fact, no correspondence whatsoever between the reasons given today and the reasons set out by the Prime Minister at the beginning. The reasons have changed all the time. I have got a list of them here, and for the sake of the record I propose to read it. I admit that I found some difficulty in organising a speech with any coherence because of the incoherence of the reasons. They are very varied.

On 30th October, the Prime Minister said that the purpose was, first, "to seek to separate the combatants"; second, "to remove the risk to free passage through the Canal".

The speech we have heard today is the first speech in which that subject has been dropped. Every other statement made on this matter since the beginning has always contained a reference to the future of the Canal as one of Her Majesty's Government's objectives, in fact, as an object of war, to coerce Egypt. Indeed, that is exactly what honourable and right honourable Gentlemen opposite believed it was all about.

Honourable Members do not do themselves justice. One does not fire in order merely to have a cease-fire. One would have thought that the cease-fire was consequent upon having fired in the first place. It could have been accomplished without starting. The other objective set out on 30th October was "to reduce the risk ... to those voyaging through the Canal." - [OFFICIAL REPORT, 30th October, 1956; Vol. 558. c. 1347.]

We have heard from the right honourable and learned Gentleman today a statement which I am quite certain all the world will read with astonishment. He has said that when we landed in Port Said there was already every reason to believe that both Egypt and Israel had agreed to cease fire.

The Minister shakes his head. If he will recollect what his right honourable and learned friend said, it was that there was still a doubt about the Israeli reply. Are we really now telling this country and the world that all these calamitous consequences have been brought down upon us merely because of a doubt? That is what he said.

Surely, there was no need. We had, of course, done the bombing, but our ships were still going through the Mediterranean. We had not arrived at Port Said. The exertions of the United Nations had already gone far enough to be able to secure from Israel and Egypt a promise to cease fire, and all that remained to be cleared up was an ambiguity about the Israeli reply. In these conditions, and against the background of these events, the invasion of Egypt still continued.

In the history of nations, there is no example of such frivolity. When I have looked at this chronicle of events during the last few days, with every desire in the world to understand it, I just have not been able to understand, and do not yet understand, the mentality of the Government. If the right honourable and learned Gentleman wishes to deny what I have said, I will give him a chance of doing so. If his words remain as they are now, we are telling the nation and the world that, having decided upon the course, we went on with it despite the fact that the objective we had set ourselves had already been achieved, namely, the separation of the combatants.

As to the objective of removing the risk to free passage through the Canal, I must confess that I have been astonished at this also. We sent an ultimatum to Egypt by which we told her that unless she agreed to our landing Ismailia, Suez and Port Said, we should make war upon her. We knew very well, did we not, that Nasser could not possibly comply? Did we really believe that Nasser was going to give in at once? Is our information from Egypt so bad that we did not know that an ultimatum of that sort was bound to consolidate his position in Egypt and in the whole Arab worId?

We knew at that time, on 29th and 30th October, that long before we could have occupied Port Said, Ismailia and Suez, Nasser would have been in a position to make his riposte. So wonderfully organised was this expedition - which, apparently, has been a miracle of military genius - that long after we had delivered our ultimatum and bombed Port Said, our ships were still ploughing through the Mediterranean, leaving the enemy still in possession of all the main objectives which we said we wanted.

Did we really believe that Nasser was going to wait for us to arrive? He did what anybody would have thought he would do, and if the Government did not think he would do it, on that account alone they ought to resign. He sank ships in the Canal, the wicked man. What did hon. Gentlemen opposite expect him to do? The result is that, in fact, the first objective realised was the opposite of the one we set out to achieve; the Canal was blocked, and it is still blocked.

The only other interpretation of the Government's mind is that they expected, for some reason or other, that their ultimatum would bring about disorder in Egypt and the collapse of the Nasser regime. None of us believed that. If honourable Gentlemen opposite would only reason about other people as they reason amongst themselves, they would realise that a Government cannot possibly surrender to a threat of that sort and keep any self-respect. We should not, should we? If somebody held a pistol at our heads and said, "You do this or we fire", should we? Of course not. Why on earth do not honourable Members opposite sometimes believe that other people have the same courage and independence as they themselves possess? Nasser behaved exactly as any reasonable man would expect him to behave.

The other objective was "to reduce the risk ... to those voyaging through the Canal." That was a rhetorical statement, and one does not know what it means. I am sorry the right honourable Gentleman the Prime Minister is not here. I appreciate why he is not here, but it is very hard to reply to him when he is not in the House, and I hope honourable Members opposite will acquit me of trying to attack him in his absence.

On 31st October, the Prime Minister said that our object was to secure a lasting settlement and to protect our nationals. What do we think of that? In the meantime, our nationals were living in Egypt while we were murdering Egyptians at Port Said. We left our nationals in Egypt at the mercy of what might have been merciless riots throughout the whole country, with no possibility whatever of our coming to their help. We were still voyaging through the Mediterranean, after having exposed them to risk by our own behaviour. What does the House believe that the country will think when it really comes to understand all this?

On 1st November, we were told the reason was "to stop hostilities" and "prevent a resumption of them". - [OFFICIAL REPORT, 1st November, 1956; Vol. 558, c. 1653.]

But hostilities had already been practically stopped. On 3rd November, our objectives became much more ambitious - "to deal with all the outstanding problems in the Middle East". - [OFFICIAL REPORT, 3rd November. 1956; Vol. 558, c. 1867.]

In the famous book Madame Bovary, there is a story of a woman who goes from one sin to another, a long story of moral decline. In this case, our ambitions soar the farther away we are from realising them. Our objective was "to deal with all the outstanding problems in the Middle East".

After having outraged our friends, after having insulted the United States, after having affronted all our friends in the Commonwealth, after having driven the whole of the Arab world into one solid phalanx, at least for the moment, behind Nasser, we were then going to deal with all the outstanding problems in the Middle East.

He said that if the United Nations would send forces to relieve us no one would be better pleased than we.

It was only a few weeks ago in this house that honourable and right honourable Gentlemen opposite sneered at every mention of the United Nations. We will deal with that.