21 March 2019, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Good afternoon ladies - and gentlemen - Thank you for coming.

First off, I must apologize for reading from this prepared script. Without my 'notes', I fear I would take us on a wildly unpredictable journey to unexpected and unusual places - as is the propensity of my wandering and inquiring mind ...

The problem is: our minds are always 'on' ... We day-dream, we fantasize, we reason, we debate and we chatter incessantly with ourselves. In so doing, we think a lot about a lot of different people and a lot of different things. Visual IDEAS ricochet through various time portals, expanding and contracting, in imagined and real geographic locations. As a result, our imaginations are constantly 'becoming' ... Collectively, our singular imagination is very much ALIVE.

To many, I have what is called, an 'active imagination'. I am sure most of you are familiar with this attribute - or, as some believe - affliction ...

This particular facility has proven to be both a blessing and a curse over my nearly 50 odd years of 'art creation'. An 'active imagination' soothes. It can also hound. An 'active imagination' has propelled me forward into new endeavours. Equally, it has held me back with compounding thoughts of catastrophic fear.

An 'active imagination' ricochets through the prisms of our minds. Ever active, it constantly produces a dazzling cascade of competing thoughts and emotions.

Initially, I was a bit surprised to be invited to speak to you today.

Some of you may recall that I spoke here eight years ago in 2011.

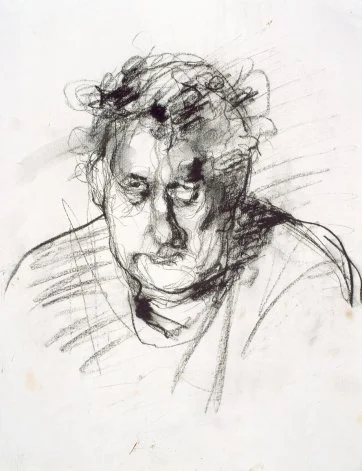

At that time, I gave a overview of my life's work as a practicing artist in the visual arts. I included a demonstration of my black & white pinhole photography, my multi-layered and multi-coloured photo-collages, my international typeface-designs now in commercial use since the 1980s, and I included an overview of my signature 'naive-surreal-folk-abstract' paintings. A slide show of those different disciplines accompanied that talk.

I made clear then, that, in the main, I am self-taught.

I learn by doing. This is my basic mantra for Life: Learn by Doing.

---

Today, I will introduce you to another discipline that I am attempting to do as best as I can - the Act and Art of Writing.

At this point in my life, in my early 60s, I am very lucky that I have the basic financial freedom to do what I want, when I want. I am, thus, at liberty to pursue my own work. That said, I do not, like so many of you here, own my own home on land that I own. There is no husband in my studio and I have no children to look after. I work and live alone, and have done so, for over 30 years. For the most part, this suits me very well.

How did I get to where I am today? --- You will need some background.

In my youth, during my 20s, I was beholden to various employment venues that governed MY TIME. When I was 32, I started my own Canadian fine furniture design practice in Toronto. In this way, I became a 'self-employed' woman at a relatively early age. For the next 14 years, I designed and produced, on commission, signature Canadian fine-furniture for many of the Greater-Toronto area 'nouveau riche'.

I learned a lot about people then and saw plenty. Interior Designer, Brian Gluckstein, who many of you may know, was a regular client. I designed and produced bedroom suites for the children of theater impresario, Garth Drabinsky. I designed artifact boxes for The Royal Ontario Museum and the front entrance of the library for the Norman Jewison's Canadian Film Centre on Bayview Avenue. I was also involved in the new kitchen design for Indigo Book founder, Heather Reisman. And, all told, I did quite well with this discipline until, quite simply, I got bored. Mainly, I grew tired of continuously having to explain the difference between mahogany, oak and pine ...

In 1998, when I was 43, I wrote my second novel, The Gilded Beaver by Anonymous. That novel documented, in semi-fictional form, much of my previous 'design' journey. It won the Hamilton Arts Council 'Best Fiction' Award in 1999.

Since then, I have devoted a greater proportion of my time to writing - first, in a 'get-wet' amateurish way, for a start-up news blog in Burlington, and then, on a more professional basis, for a larger news blog in Hamilton - Raise the Hammer - under the editorial tutelage of the gifted Ryan McGreal.

During the following decade, I began to hone my journalistic skills, not only as a writer of factual stories, but as a 'photo-journalist'. I started to add photographs to my articles. One, then two, then three. Soon thereafter, I started to add short video clips. I would often spend an hour or more with an engaging personality and video-tape it - first on my Canon camera - then latterly, on my Apple ipod. I learned to edit these single-take interviews down to 8 to 10 minute short films that would accompany my articles. For five years, I organically learned about the tools and language of film - albeit on a very small scale. I was learning by doing.

During that period, I began to craft short stories again, just for the sheer fun of it. I wrote an imagined short story about World War 1. In that tall tale, a broken shell-shock soldier returns from the frontlines of Vimy to a rural family where all are struggling to survive in the aftermath of The Great War. Initially, in the story, it does not go well for him. But the tale does have a happy ending! -- Two years later, I was lucky to have this unpublished work selected as the LAST story of a short story anthology, entitled 'ENGRAVED: Canadian Stories of World War One'. Being the last story in a collection of short stories is a very good place to be. It closes out the volume in both tone and imagery.

I then became intrigued by the conceptual possibility of turning that good short story into a short film.

I proceeded to learn what I had to do in order to do that. This is very much the way my mind works ... The mind is constantly asking - Who, What, When, Where, Why and HOW?

During the early development of my first narrative short film, I joined several local Facebook film-making groups and became a founding member of FAB - the Filmmakers Alliance of Burlington. Our monthly meet-ups at a local coffee shop established a local film production network where newbies (like me), as well as veterans of the trade, could get together to chat about their latest projects.

Within a year, I had finished the final draft of my first screenplay for 'The Frozen Goose'. I then put out a casting call to local actors and actresses - and cast the five needed to tell the story. I hired the film crew: the cameraman, sound recordist, prop master, and borrowed and bought period costumes for the production. I secured insurance permits for the shooting locations on both public and private lands, and began summer rehearsals with the two starring children.

In short, within one brief year, I became a PRODUCER, DIRECTOR and WRITER of 'The Frozen Goose'. Financing for the film was secured from multiple sources: family, friends, associates and an on-line IndieGoGo campaign. I can proudly say, I shot, edited and packaged the final 25 minute film - on time and 'on budget' - for just under $12,000.

The raw digital footage was shot during the coldest week in February of 2016. By the fall of that same year, the commissioned score, titles, credits and final edit were completed. The film poster was designed by me and I transferred the final film onto a 'For Sale' limited-run DVD. It sold out within three weeks.

'The Frozen Goose' premiered at the Art Gallery of Burlington on September 6th of 2016, with the then Mayor, Rick Goldring, and the now CEO, Robert Stevens, presiding. There were two sold-out screenings with a toe-tapping musical interlude performed by the local Celtic trio, Whiskey Epiphany. That gifted trio was fronted by the phenomenally gifted fiddler, David McLean. David's merry music can be heard throughout the film.

'The Frozen Goose' then went on to screen, twice, at the Hamilton Film Festival in 2017. At the end of that year, it aired on COGECO and CABLE 14 and it was finally picked up by a Canadian distributor for the cross-national audio-visual school and library markets in Canada.

DONE!

From start to finish, I believe I made a not too shabby FIRST narrative short film. I knew it wasn't perfect - by an stretch - but, on route, I had learned a great deal more about the Act and Art of storytelling IN FILM.

I tell you this now because I hope to give you a better understanding of how 'words composed on the page' become, 'words and visuals delivered on the screen'.

Every great movie starts with a script.

---

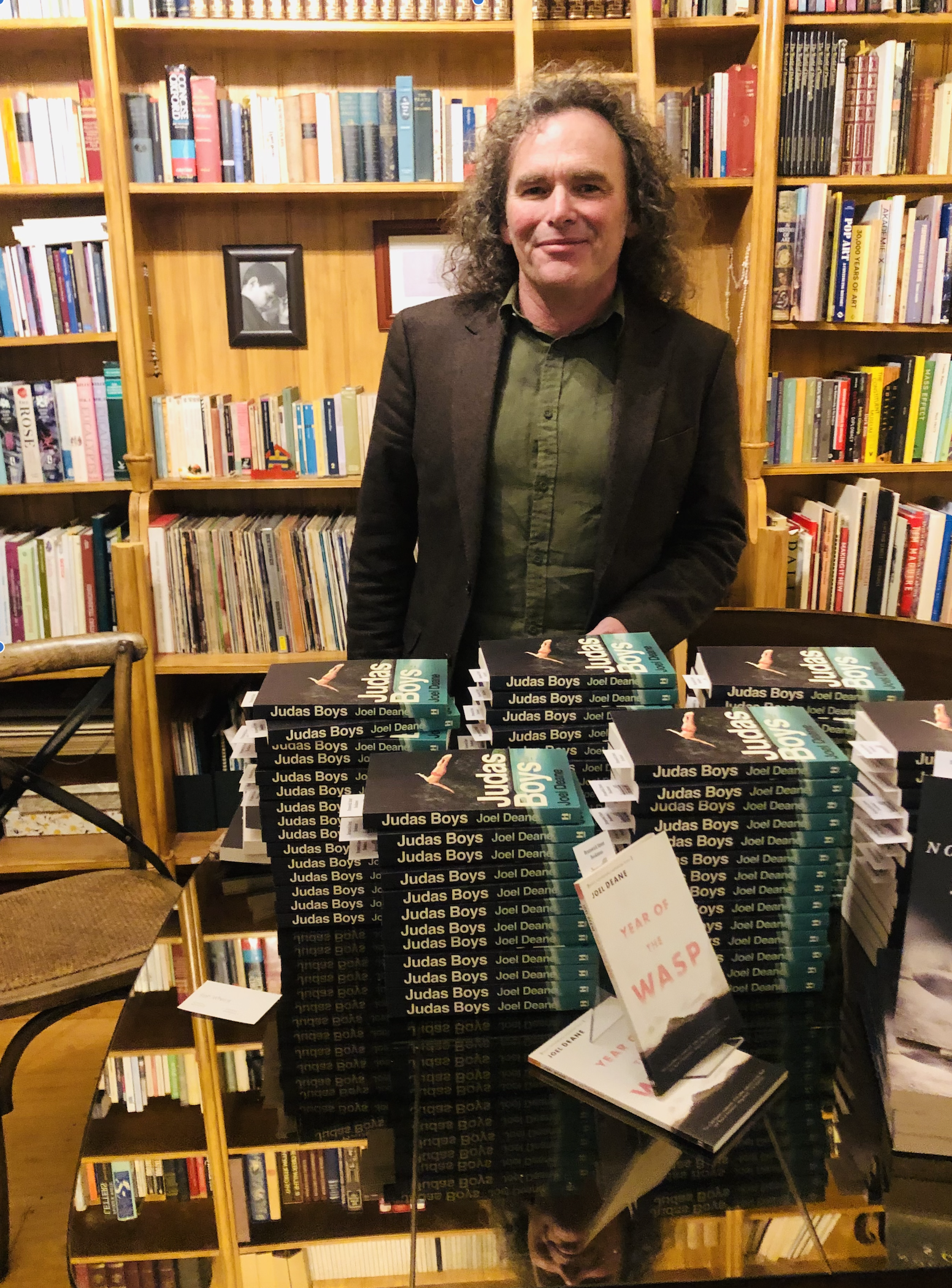

Recently, I completed my third novel, TRILLIUM. I wrote it during most of last year, in 2018.

From February to October, I sat down at my laptop and wrote diligently from 10am to 6pm, five days a week, taking only a one hour break for lunch to clear my head and re-charge. By mid-October, I sent the manuscript off to my chosen printers in Quebec and did a quick proof of the cover design and cover specifications. I was very pleased with myself that I was 'on schedule' when I released it in a limited Canadian produced 'Artist First Edition' at the end of October. -- DONE!

But Live and LEARN.

That 'Artist First Edition' is - regrettably - far from perfect. I had goofed big time.

After a much-needed break and breather, I casually went back to look at the then published book. I was dismayed to discovered I had made numerous silly mistakes, too-many-to-mention. Ashamed at my gaffs, I immediately withdrew the book from the marketplace and began an intense clean-up.

The FINAL work has just been released as an updated 340 page paperback and e-book in January of this year. Today, I continue to kick myself at my prior impatience 'to-get-it-to-print'. I had made an embarrassing error. BUT, there is no point in crying over spilt milk. What's done is done. ...

We live and we learn ...

Today, I am offering you the remaining IMPERFECT 'Artist First Editions' for just $20 per copy. Ironically, for a serious collector, that's a surprisingly good deal for a 'first edition' novel.

Otherwise, I have promo cards available for you on the so that you can find it on-line.

---

This new written work of mine, this 340 page historical novel, TRILLIUM, is very different from my prior attempts at factual and fictional story-telling. Instead of a standard protagonist and antagonist, or a somewhat predictable love triangle, I crafted an extended multi-generational cast of colourful and challenging characters who cover 250 years of settlement and growth in the wine-making district of Niagara. It is a full-fledged 'adult' novel that concerns itself with on-going topics of concern to adults. I wanted a broad palette to explore a number of different and timely issues.

This wide-ranging story - with all its up-and-downs and roll-a-rounds - in love, lust, revenge, larceny and a mysterious murder - cloaks the real purpose of any story.

And what, you might wonder, is that?

What is the purpose of any story?

Fundamentally - every story - ever told - has a moral - be it focused on Virtue or Vice.

TRILLIUM, the novel, isn't just about lip-smacking wine-making, salacious and furtive lusting, bug-eyed young love or the alluring glimmer of gold. No. Trillium is about morality. It is about the Good in people. It is about the Bad in people. It is about the choices people make about the Right Way and the Wrong Way of living a human life. How we, as people, LIVE is amplified by preceding generations who, covertly and overtly, shape and nurture the next generation ...

TRILLIUM is about Life.

The underlying theme of TRILLIUM, from start to finish, focuses on my growing concern about our apparent diminishing capacity to survive as a healthy and compassionate species on this amazing planet. Yes, heavy and heady stuff. ... But this singular and primary thought did guide me in the writing of this new work.

TRILLIUM deliberately weaves in and out of an assortment of moral dilemmas. Some are heart-breaking and tragic. Some are comical, witty and wise. Some are downright diabolical and evil, while some are pure and angelic. I wrote TRILLIUM to share a broad perspective about humanity. It is filled with the capricious, the colourful and the careless - all kinds of real-time personalities.

---

I would now like to dive a little bit deeper into the ACT and ART of 'writing a story. What MAKES a Writer Write? --- What compels a person to do set down and put words to paper? --- Why bother?

---

It's a bit of a long-winded answer, but please, bear with me.

Ever since I can remember, I have had a writing box. Most writers do.

This box is a compost heap of peripatetic ideas and sideswiped observations.

Something will catch a writer’s eye or ear or fancy and it will get jotted down, then, later, tossed into the box. Stubby pencil scratches on found bits of paper, full-length manuscripts of fluttering foolscap, half-composed computer print-outs or verdant wet-pen epistles - ALL these items get tossed into the box.

There, IDEAS will sit for a time to germinate. Two days - or two decades - per item is not an uncommon gestation period. Why? Because IDEA SEEDS vary.

My writing box is a living ‘WORDS-in-progress’ garden.

When I return at different times to view my young shoots, I often find that some ideas have not taken root (pithy but pointless) --- or that others must be zealously weeded out (verbose ravings). Yet, I will also often see the formation of a healthy new bud- especially when a single word reverberates. New growth struggles on an old growth IDEA. One thought - or one IDEA - may pollinate another. With these latter discoveries, I will start to feverishly prune-edit, cultivate-rewrite and otherwise happily tend to my quixotic word garden.

Some tales began long ago and have only recently come to final fruition. TRILLIUM was just such a story. I wrote the preliminary outline for this work over 10 years ago. Back then, I had an inkling that I needed to write a long, involved, rooted, yet evolving story - about rural family life ...

Other stories in my writing box have been grafted onto different ideas creating hybrids. 'The Frozen Goose' short story then screenplay falls into this category.

And some stories, I know, to a seasoned and urban urbane editor, may still need some heavy pruning .... However, I have kept these scraggly 'wild ones’ because they still radiate an exploratory and experimental sheen. I find they have their own rare merit - and honest beauty. And I know, if left longer to germinate, those struggling seeds will eventually sprout too.

...

Well-told stories are a delight to our senses. Our listening imaginations discern certain features repeated in pattern. Certain repeated words shimmer in different contexts. When words reverberate through us, they give us meaning. Like the word, 'colour', heard often here today. That word is reverberating in our collective mind ...

Stories are also ephemeral. The stories we hear, read, see or think today will be gone tomorrow. They will have grown and gently morphed into something else overnight as we artfully re-arrange them into our own personal perceptions and root them in our muddy memories. In this way, scintillating private stories, shared by others, become linked to intimate and well-loved stories of our own.

Soon, a good story, well told, becomes everyone's story.

...

So, how does one become a writer?

I believe it starts at a very young age when the joy-filled discovery of words is so fresh and intoxicating. Learning a new word suddenly explains, very clearly, what we are struggling so hard to say. -- Yes! No! - and then - Maybe ....

There is an immediate resonance with a new word discovery. New words sharpen our perceptions and refine our feelings. Developing vocabularies help us to better understand who we are becoming ...

In my case, I gave my first hand-written poem to my mother - 'Flowers In May' - when I was 9 years old. At the time, it was a bold act. I was showing and giving her a testament of my deep love of language. "See mum? -- Read what I have just written!"

At a very early age, I became a ferocious reader and, thanks to my parents, I discovered the attendant pleasures of owning a well-thumbed dictionary and a good thesaurus.

Words, in and of themselves, became sparkling phonetic jewels of wonderment.

I read and read and read ...,.

...

In my late teens, in the mid 1970, when thrust from the gentle rural countryside of South-western Ontario into the heady cosmopolitan environment at the University of Toronto to do a B.A. in Literature and Philosophy, I was instantly seduced by the surprising rhetorical possibilities of language.

I had long known there was emotive logic and persuasive argument - but to learn that ‘rhetoric’ itself was a studied and applied linguistic ‘science’ - well - that was eye-opening. I immediately wanted to understand what differentiated the written word of lawyers, say, from those of a journalist, or a writer of science fiction, or a passionate playwright or an enigmatic poet. I soon learned that each sub-discipline within the writing realm had its own particular rules of conduct and delivery.

It also seemed to me that the worlds of politics and commerce constantly erupted in all these types of writing. Politics and commerce shaped the tone of the language used. When a lawyer spoke or wrote of law, it was very different than when a playwright or poet spoke or wrote about law. To this day, Shakespeare remains the indisputable Master interpreter of these different shades of meaning according to their different roots of usage. He knew well that a speaker's role implies different meaning .

...

Playing with language became an obsessive preoccupation. Bawdy and cheeky limericks, ethereal and dainty haikus and popular pop-song lyrics jostled with the playfulness of words. As a concrete example, The Beatles group of the 1960s understood this playfulness very well. --- They invented - 'coo-coo-ca-choo' .... 'I am the Walrus' ... and re-worked 'I wanna hold your hand' to beguile us.

At university, I also began to understand that men and women DO experience and interpret the world very differently. It is evident in the different tone and choice of words used to express differing points of view. I explored a diversity of these sex-based ‘voices’ in my first book of published poetry, 'On Top of Mount Nemo'. Throughout that very early work, I played with these different sexual points-of-view and twirled them within the multiple refractions of our common perceptual prism. Words were such fun.

After graduating with a four-year Lit & Philosophy degree, with an independent study year at the University of Edinburgh where I focused on the history of the English language, and dusty too from several continental sojourns - I then settled down to the onerous task of ‘working-for-a-living' from 'dawn-to-dusk’.

I naturally gravitated towards entry level jobs that dealt with words, and was particularly drawn to Advertising and Copywriting. I started out as an Assistant Editor at an radio industry magazine, the FM Guide, under the supervision of Andrew Marshall, the proprietor, married to Canadian labour historian, Heather Robertson. Andrew and Heather were didactic wordsmiths who helped sharpen my ear.

Other short term jobs followed that allowed me to perceive and evaluate what I increasingly considered to be a loosely federated Advertising Empire that psychically dominated North America ...

I worked, for awhile, as a production assistant for a busy commercial film house and ran scripts and story boards back and forth to advertising clients.

Within this advertising empire, I soon learned that we think and become what we watch and consume. In this instance, the connecting and resonating link is the language of ‘sales’.

Sales is generated by believable or catchy advertising copy. Punchy slogans and riveting sound bites still seduce even the most wary and wry.

During the decade of the 1980′s, while setting up my own fine furniture design business in Toronto, my mind continued to race forward to find those literary nuggets that endured beyond the advertising hype.

When the 1990′s were upon us, the surround-sounds of multi-media seemed intensely focused on the emerging cyber-sphere and its nascent McLuhan-esque offspring: the internet.

Writing, and even reading, took on new dimensions as the lines slowly started to blur between the Real and the Un-Real. Television and Photography increasingly replaced the Printed Word. Vision soon dominated. The once prized and eloquent use of language became the cheap side-kick to a riveting photo image.

Think of 'Tony the Tiger' or 'the Tiger in your tank' based on an unbelievably engaging visual. Written words became spit as needed. In North America, we were increasingly being sold the IDEA that we needed everything – our body urges and our emotional needs – instantly gratified - with no thought of consequence. Plugged in, we sucked it all in, and soon every last one of us became addicted.

Computers, (with their oddly-named 'mice'), were soon added to our already plugged-in homes that housed those flickering tell-a-vision windows of fabricated reality.

...

In the middle of the 1990′s, the explosive Bre-X gold fraud scandal, (of salting a gold find in Borneo), was one of many riveting news items. We watched as 'Canada the Good' quietly fell from grace in the global business community. Ordinary investors lost faith and trust in the hustlers and hustle of the markets. Dot and telecom technology stocks floundered. Many collapsed overnight. Research-in-Motion and Nortel went bankrupt. Insider trading scandals and continued corporate-accounting fraud rattled the cages of commerce. Enron became a household word. And then, Dolly, the sheep, was cloned ...

Yet, it seemed to me, that even then - underlying this hurly-burly consumption and destruction - there were certain immutable Truths.

The Earth continues to revolve around the Sun.

This fact is unlikely to change anytime soon.

Towards the end of the 90′s, as I was entering my fourth decade on this planet, I began my second novel, The Gilded Beaver By Anonymous. Yes, it encapsulated much of what I had gleaned over the past decade as a designer. But also in that work, I was exploring and writing like a psychic geologist. ... I was constantly looking for noteworthy nuggets to pass along ... After winning the writing award for that work, I knew I was on to something ... I quietly kept at it and wrote when I could, tossing more SEED IDEAS into my writing box garden.

...

Something marvelous seemed to occur when we tipped into the twenty-first century. Remember? The century clocked over from 1999 to 2000. -- Aside from the doomsday clock-watchers, we were filled with a fresh new optimism and a sincere hope for our global future. All the dilapidated debris of the previous millennium momentarily disappeared and there was this unexpected gush of euphoria. -- We seemed to be on the right path, moving in the right direction ...

And yet.

Here we are today, in the final year of a second bloody and anxious decade, 2019.

We seem to have lost not only our footing but our moral centers.

The prospect of a new nuclear war and the continuous threats of ‘terrorism’ hang over our heads like threatening storm clouds. Outrageous atrocities – man’s inhumanity to man – unimagined even a short time ago – are now routinely reported. We addictively watch global events unfold on our televisions or scroll and swipe our way through social media on the internet. We're permanently plugged into our preferred apps and constantly engaging on our preferred social platforms. We hunger and we thirst for MORE.

Meanwhile, men - and yes, it is mostly men - continue to fight territorial squabbles over precious and diminishing natural resources on our finite planet.

Everyone is shoving, pushing and grabbing.

Camps of ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ are erupting everywhere. ---

It's starting to look like it's all going to explode soon ....

We seem to be on the edge of a cataclysmic melt-down ...

And yet – I ask you ----

Are these media-generated stories the real stories?

Are they the enduring stories that we all need to survive?

As a mature and aging woman on this planet, I do not think so.

We do not need to self-destruct.

...

To my mind, the time has come to re-discover the precious precision of words.

From my end, to sharpen my pen and strengthen my voice, I entered the Humber School of Writer's 'Graduate Creative Writing Program' in 2004. For the next eight months, I corresponded with two-time Giller Prize winner, M.G.Vassanji: a very seasoned Asian-Indian writer, best known for his Tanzanian-Toronto-centric novels - 'The Book of Secrets' and 'The In-between Worlds of Vikram Lall.'

Vassanji and I slowly worked back and forth through the unfinished snippets and short stories smoldering in my writing box.

Some seed IDEAS he liked, and some SHOOTS he didn’t. His periodic question marks in the columns of my manuscripts made me re-think my structures, my use of styles and my intentions. His attentive and thoughtful readings helped me to refine my essential reason for writing.

He helped me further define my future responsibility as a writing artist.

--- In many ways, it is the oldest story in the book. ---

Any true writer - any real writer worth their salt - is - at core - a CARETAKER.

Today, it seems this early story-telling Truth must be told again and again, in every language, in every medium, and with every voice: We are ALL Caretakers.

As a writing artist, I have planted my thoughts in a variety of different ‘voices’ to reflect the manners and mores of our times.

I now pass them on to you in my latest novel offering - TRILLIUM.

Please let my thoughts ricochet within you.

Cross-pollinate. Re-cultivate them.

Find again the sweet joy of warbling words.

And then, CARE TAKE …

Use the potent power of our shared stories.

Thank you.