3 April 1982, Westminster, London, UK

The House meets this Saturday to respond to a situation of great gravity. We are here because, for the first time for many years, British sovereign territory has been invaded by a foreign power. After several days of rising tension in our relations with Argentina, that country's armed forces attacked the Falkland Islands yesterday and established military control of the islands.

Yesterday was a day of rumour and counter-rumour. Throughout the day we had no communication from the Government of the Falklands. Indeed, the last message that we received was at 21.55 hours on Thursday night, 1 April. Yesterday morning at 8.33 am we sent a telegram which was acknowledged. At 8.45 am all communications ceased. I shall refer to that again in a moment. By late afternoon yesterday it became clear that an Argentine invasion had taken place and that the lawful British Government of the islands had been usurped.

I am sure that the whole House will join me in condemning totally this unprovoked aggression by the Government of Argentina against British territory. [HON. MEMBERS: "Hear, hear".] It has not a shred of justification and not a scrap of legality.

It was not until 8.30 this morning, our time, when I was able to speak to the governor, who had arrived in Uruguay, that I learnt precisely what had happened. He told me that the Argentines had landed at approximately 6 am Falkland's time, 10 am our time. One party attacked the capital from the landward side and another from the seaward side. The governor then sent a signal to us which we did not receive.

Communications had ceased at 8.45 am our time. It is common for atmospheric conditions to make communications with Port Stanley difficult. Indeed, we had been out of contact for a period the previous night.

The governor reported that the Marines, in the defence of Government House, were superb. He said that they acted in the best traditions of the Royal Marines. They inflicted casualties, but those defending Government House suffered none. He had kept the local people informed of what was happening through a small local transmitter which he had in Government House. He is relieved that the islanders heeded his advice to stay indoors. Fortunately, as far as he is aware, there were no civilian casualties. When he left the Falklands, he said that the people were in tears. They do not want to be Argentine. He said that the islanders are still tremendously loyal. I must say that I have every confidence in the governor and the action that he took.

I must tell the House that the Falkland Islands and their dependencies remain British territory. No aggression and no invasion can alter that simple fact. It is the Government's objective to see that the islands are freed from occupation and are returned to British administration at the earliest possible moment.

Argentina has, of course, long disputed British sovereignty over the islands. We have absolutely no doubt about our sovereignty, which has been continuous since 1833. Nor have we any doubt about the unequivocal wishes of the Falkland Islanders, who are British in stock

634

and tradition, and they wish to remain British in allegiance. We cannot allow the democratic rights of the islanders to be denied by the territorial ambitions of Argentina.

Over the past 15 years, successive British Governments have held a series of meetings with the Argentine Government to discuss the dispute. In many of these meetings elected representatives of the islanders have taken part. We have always made it clear that their wishes were paramount and that there would be no change in sovereignty without their consent and without the approval of the House.

The most recent meeting took place this year in New York at the end of February between my hon. Friend the Member for Shoreham, (Mr. Luce) accompanied by two members of the islands council, and the Deputy Foreign Secretary of Argentina. The atmosphere at the meeting was cordial and positive, and a communiqué was issued about future negotiating procedures. Unfortunately, the joint communiqué which had been agreed was not published in Buenos Aires.

There was a good deal of bellicose comment in the Argentine press in late February and early March, about which my hon. Friend the Minister of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs expressed his concern in the House on 3 March following the Anglo-Argentine talks in New York. However, this has not been an uncommon situation in Argentina over the years. It would have been absurd to dispatch the fleet every time there was bellicose talk in Buenos Aires. There was no good reason on 3 March to think that an invasion was being planned, especially against the background of the constructive talks on which my hon. Friend had just been engaged. The joint communiqué on behalf of the Argentine deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and my hon. Friend read: "The meeting took place in a cordial and positive spirit. The two sides reaffirmed their resolve to find a solution to the sovereignty dispute and considered in detail an Argentine proposal for procedures to make better progress in this sense." There had, of course, been previous incidents affecting sovereignty before the one in South Georgia, to which I shall refer in a moment. In December 1976 the Argentines illegally set up a scientific station on one of the dependencies within the Falklands group—Southern Thule. The Labour Government attempted to solve the matter through diplomatic exchanges, but without success. The Argentines remained there and are still there.

Two weeks ago—on 19 March—the latest in this series of incidents affecting sovereignty occurred; and the deterioration in relations between the British and Argentine Governments which culminated in yesterday's Argentine invasion began. The incident appeared at the start to be relatively minor. But we now know it was the beginning of much more.

The commander of the British Antartic Survey base at Grytviken on South Georgia—a dependency of the Falkland Islands over which the United Kingdom has exercised sovereignty since 1775 when the island was discovered by Captain Cook—reported to us that an Argentine navy cargo ship had landed about 60 Argentines at nearby Leith harbour. They had set up camp and hoisted the Argentine flag. They were there to carry out a valid commercial contract to remove scrap metal from a former whaling station.

The leader of the commercial expedition, Davidoff, had told our embassy in Buenos Aires that he would be going

635

to South Georgia in March. He was reminded of the need to obtain permission from the immigration authorities on the island. He did not do so. The base commander told the Argentines that they had no right to land on South Georgia without the permission of the British authorities. They should go either to Grytviken to get the necessary clearances, or leave. The ship and some 50 of them left on 22 March. Although about 10 Argentines remained behind, this appeared to reduce the tension.

In the meantime, we had been in touch with the Argentine Government about the incident. They claimed to have had no prior knowledge of the landing and assured us that there were no Argentine military personnel in the party. For our part we made it clear that, while we had no wish to interfere in the operation of a normal commercial contract, we could not accept the illegal presence of these people on British territory.

We asked the Argentine Government either to arrange for the departure of the remaining men or to ensure that they obtained the necessary permission to be there. Because we recognised the potentially serious nature of the situation, HMS "Endurance" was ordered to the area. We told the Argentine Government that, if they failed to regularise the position of the party on South Georgia or to arrange for their departure, HMS "Endurance" would take them off, without using force, and return them to Argentina.

This was, however, to be a last resort. We were determined that this apparently minor problem of 10 people on South Georgia in pursuit of a commercial contract should not be allowed to escalate and we made it plain to the Argentine Government that we wanted to achieve a peaceful resolution of the problem by diplomatic means. To help in this, HMS "Endurance" was ordered not to approach the Argentine party at Leith but to go to Grytviken.

But it soon became clear that the Argentine Government had little interest in trying to solve the problem. On 25 March another Argentine navy ship arrived at Leith to deliver supplies to the 10 men ashore. Our ambassador in Buenos Aires sought an early response from the Argentine Government to our previous requests that they should arrange for the men's departure. This request was refused. Last Sunday, on Sunday 28 March, the Argentine Foreign Minister sent a message to my right hon. and noble Friend the Foreign Secretary refusing outright to regularise the men's position. Instead it restated Argentina's claim to sovereignty over the Falkland Islands and their dependencies.

My right hon. and noble Friend the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary then sent a message to the United States Secretary of State asking him to intervene and to urge restraint.

By the beginning of this week it was clear that our efforts to solve the South Georgia dispute through the usual diplomatic channels were getting nowhere. Therefore, on Wednesday 31 March my right hon. and noble Friend the Foreign Secretary proposed to the Argentine Foreign Minister that we should dispatch a special emissary to Buenos Aires.

Later that day we received information which led us to believe that a large number of Argentine ships, including an aircraft carrier, destroyers, landing craft, troop carriers and submarines, were heading for Port Stanley. I contacted President Reagan that evening and asked him to intervene with the Argentine President directly. We promised, in the meantime, to take no action to escalate the dispute for fear of precipitating—[Interruption]—the very event that our efforts were directed to avoid. May I remind Opposition Members—[Interruption]—what happened when, during the lifetime of their Government——

Mr. J. W. Rooker (Birmingham, Perry Barr)

We did not lose the Falklands.

The Prime Minister

—Southern Thule was occupied. It was occupied in 1976. The House was not even informed by the then Government until 1978, when, in response to questioning by my hon. Friend the Member for Shoreham (Mr. Luce), now Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the hon. Member for Merthyr Tydfil (Mr. Rowlands) said: "We have sought the resolve the issue though diplomatic exchanges between the two Governments. That is infinitely preferable to public denunciations and public statements when we are trying to achieve a practical result to the problem that has arisen."—[Official Report, 24 May 1978; Vol. 950, c. 1550–51.]"

Mr. Edward Rowlands (Merthyr Tydfil)

The right hon. Lady is talking about a piece of rock in the most southerly part of the dependencies, which is completely uninhabited and which smells of large accumulations of penguin and other bird droppings. There is a vast difference—a whole world of difference—between the 1,800 people now imprisoned by Argentine invaders and that argument. The right hon. Lady should have the grace to accept that.

The Prime Minister

We are talking about the sovereignty of British territory—[Interruption]—which was infringed in 1976. The House was not even informed of it until 1978. We are talking about a further incident in South Georgia which—as I have indicated—seemed to be a minor incident at the time. There is only a British Antarctic scientific survey there and there was a commercial contract to remove a whaling station. I suggest to the hon. Gentleman that had I come to the House at that time and said that we had a problem on South Georgia with 10 people who had landed with a contract to remove a whaling station, and had I gone on to say that we should send HMS "Invincible", I should have been accused of war mongering and sabre rattling.

Information about the Argentine fleet did not arrive until Wednesday. Argentina is, of course, very close to the Falklands—a point that the hon. Member for Merthyr Tydfil cannot and must not ignore—and its navy can sail there very quickly. On Thursday, the Argentine Foreign Minister rejected the idea of an emissary and told our ambassador that the diplomatic channel, as a means of solving this dispute, was closed. President Reagan had a very long telephone conversation, of some 50 minutes, with the Argentine President, but his strong representations fell on deaf ears. I am grateful to him and to Secretary Haig for their strenuous and persistent efforts on our behalf.

On Thursday, the United Nations Secretary-General, Mr. Perez De Cuellar, summoned both British and Argentine permanent representatives to urge both countries to refrain from the use or threat of force in. the South Atlantic. Later that evening we sought an emergency meeting of the Security Council. We accepted the appeal of its President for restraint. The Argentines

said nothing. On Friday, as the House knows, the Argentines invaded the Falklands and I have given a precise account of everything we knew, or did not know, about that situation. There were also reports that yesterday the Argentines also attacked South Georgia, where HMS "Endurance" had left a detachment of 22 Royal Marines. Our information is that on 2 April an Argentine naval transport vessel informed the base commander at Grytviken that an important message would be passed to him after 11 o'clock today our time. It is assumed that this message will ask the base commander to surrender.

Before indicating some of the measures that the Government have taken in response to the Argentine invasion, I should like to make three points. First, even if ships had been instructed to sail the day that the Argentines landed on South Georgia to clear the whaling station, the ships could not possibly have got to Port Stanley before the invasion. [Interruption.] Opposition Members may not like it, but that is a fact.

Secondly, there have been several occasions in the past when an invasion has been threatened. The only way of being certain to prevent an invasion would have been to keep a very large fleet close to the Falklands, when we are some 8,000 miles away from base. No Government have ever been able to do that, and the cost would be enormous.

Mr. Eric Ogden (Liverpool, West Derby)

Will the right hon. Lady say what has happened to HMS "Endurance"?

The Prime Minister

HMS "Endurance" is in the area. It is not for me to say precisely where, and the hon. Gentleman would not wish me to do so.

Thirdly, aircraft unable to land on the Falklands, because of the frequently changing weather, would have had little fuel left and, ironically, their only hope of landing safely would have been to divert to Argentina. Indeed, all of the air and most sea supplies for the Falklands come from Argentina, which is but 400 miles away compared with our 8,000 miles.

That is the background against which we have to make decisions and to consider what action we can best take. I cannot tell the House precisely what dispositions have been made—some ships are already at sea, others were put on immediate alert on Thursday evening.

The Government have now decided that a large task force will sail as soon as all preparations are complete. HMS "Invincible" will be in the lead and will leave port on Monday.

I stress that I cannot foretell what orders the task force will receive as it proceeds. That will depend on the situation at the time. Meanwhile, we hope that our continuing diplomatic efforts, helped by our many friends, will meet with success.

The Foreign Ministers of the European Community member States yesterday condemned the intervention and urged withdrawal. The NATO Council called on both sides to refrain from force and continue diplomacy.

The United Nations Security Council met again yesterday and will continue its discussions today. [Laughter.] Opposition Members laugh. They would have been the first to urge a meeting of the Security Council if we had not called one. They would have been the first to urge restraint and to urge a solution to the problem by diplomatic means. They would have been the first to accuse us of sabre rattling and war mongering.

Mr. Tam Dalyell (West Lothian)

The right hon. Lady referred to our many friends. Have we any friends in South America on this issue?

The Prime Minister

Doubtless our friends in South America will make their views known during any proceedings at the Security Council. I believe that many countries in South America will be prepared to condemn the invasion of the Falklands Islands by force.

We are now reviewing all aspects of the relationship between Argentina and the United Kingdom. The Argentine chargé d'affaires and his staff were yesterday instructed to leave within four days.

As an appropriate precautionary and, I hope, temporary measure, the Government have taken action to freeze Argentine financial assets held in this country. An order will be laid before Parliament today under the Emergency Laws (Re-enactments and Repeals) Act 1964 blocking the movement of gold, securities or funds held in the United Kingdom by the Argentine Government or Argentine residents.

As a further precautionary measure, the ECGD has suspended new export credit cover for the Argentine. It is the Government's earnest wish that a return to good sense and the normal rules of international behaviour on the part of the Argentine Government will obviate the need for action across the full range of economic relations.

We shall be reviewing the situation and be ready to take further steps that we deem appropriate and we shall, of course, report to the House.

The people of the Falkland Islands, like the people of the United Kingdom, are an island race. Their way of life is British; their allegiance is to the Crown. They are few in number, but they have the right to live in peace, to choose their own way of life and to determine their own allegiance. Their way of life is British; their allegiance is to the Crown. It is the wish of the British people and the duty of Her Majesty's Government to do everything that we can to uphold that right. That will be our hope and our endeavour and, I believe, the resolve of every Member of the House.

Mr. Michael Foot (Ebbw Vale)

It was obviously essential that the House of Commons should be recalled on this occasion. I thank the Prime Minister for the decision to do so. I can well understand the anxiety and impatience of many of my hon. Friends on the Back Benches who voted in the Division a few minutes ago and who desire to have full and proper time to examine all the aspects of this issue. I shall return to that aspect of the matter in a few minutes.

I first wish to set on record as clearly as I possibly can what we believe to be the international rights and wrongs of this matter, because I believe that one of the purposes of the House being assembled on this occasion is to make that clear not only to the people in our country but to people throughout the world.

The rights and the circumstances of the people in the Falkland Islands must be uppermost in our minds. There is no question in the Falkland Islands of any colonial dependence or anything of the sort. It is a question of people who wish to be associated with this country and who have built their whole lives on the basis of association with this country. We have a moral duty, a political duty and every other kind of duty to ensure that that is sustained.

The people of the Falkland Islands have the absolute right to look to us at this moment of their desperate plight, just as they have looked to us over the past 150 years. They are faced with an act of naked, unqualified aggression, carried out in the most shameful and disreputable circumstances. Any guarantee from this invading force is utterly worthless—as worthless as any of the guarantees that are given by this same Argentine junta to its own people.

We can hardly forget that thousands of innocent people fighting for their political rights in Argentine are in prison and have been tortured and debased. We cannot forget that fact when our friends and fellow citizens in the Falkland Islands are suffering as they are at this moment.

On the merits of the matter, we hope that the question is understood throughout the world. In that respect I believe that the Government were right to take the matter to the United Nations. It would have been delinquency if they had not, because that is the forum in which we have agreed that such matters of international right and international claim should be stated.

Whatever else the Government have done—I shall come to that in a moment—or not done, I believe that it was essential for them to take our case to the United Nations and to present it with all the force and power of advocacy at the command of this country. The decision and the vote in the United Nations will take place in an hour or two's time. I must say to people there that we in this country, as a whole, irrespective of our party affiliations, will examine the votes most carefully.

I was interested to hear how strongly the President of France spoke out earlier this morning. I hope that every other country in the world will speak in a similar way.

If, at the United Nations this afternoon, no such declaration were made—I know that it would be only a declaration at first, but there might be the possibility of action there later—not merely would it be a gross injury to the rights of the people of the Falkland Islands, not merely would it be an injury to the people of this country, who have a right to have their claims upheld in the United Nations, but it would be a serious injury to the United Nations itself. It would enhance the dangers that similar, unprovoked aggressions could occur in other parts of the world.

That is one of the reasons why we are determined to ensure that we examine this matter in full and uphold the rights of our country throughout the world, and the claim of our country to be a defender of people's freedom throughout the world, particularly those who look to us for special protection, as do the people in the Falkland Islands.

I deal next with the Government's conduct in the matter. What has happened to British diplomacy? The explanations given by the right hon. Lady, when she managed to rise above some of her own party arguments—they were not quite the exclusive part of her speech—were not very full and not very clear. They will need to be made a good deal more ample in the days to come.

The right hon. Lady did not quote fully the response of Lord Carrington, the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, at his press conference yesterday. She referred to the Minister of State, who, according to Lord Carrington, "had just been in New York discussing with Mr. Ross, his opposite number, the question of resumption of talks with the Argentine Government about the problems of the Falkland Islands. And they had had a talk and come to an agreement. Mr. Ross went back to the Argentine and a number of things came up and they sent a message which"——" I emphasise the words—— "I have not yet had time to reply to." Lord Carrington added: "So there was every reason to suppose that the Argentines were interested in negotiations." Those talks took place on 27 February. The right hon. Lady gave an account of these negotiations. But from what has happened it seems that the British Government have been fooled by the way in which the Argentine junta has gone about its business. The Government must answer for that as well as for everything else.

What about British communications and British intelligence? The Guardian states today in a leading article: "This country devotes a greater proportion of its annual output to its armed forces than any other Western country, with the exception of the United States. It has extensive diplomatic and intelligence gathering activities. And all of that gave Mrs. Thatcher, Lord Carrington and Mr. Nott precisely no effective cards when the Argentine navy moved." I should be very surprised to hear, because of some of the previous debates and discussions on the crises that have arisen with the Argentine, that the British Government did not have better intelligence than that. So good was our intelligence that, although the Prime Minister now tells us that the invasion took place at 10 am yesterday, the Lord Privy Seal—I know that he has apologised for some of his remarks—told the House of Commons and the British people: "We are taking appropriate military and diplomatic measures to sustain our rights under international law and in accordance with the provisions of the United Nations charter."—[Official Report, 2 April 1982; Vol. 21, c. 571.]" When he was saying that, it was the Argentine Government who were taking appropriate military, not diplomatic, measures to enforce their will.

The right hon. Lady, the Secretary of State for Defence and the whole Government will have to give a very full account of what happened, how their diplomacy was conducted and why we did not have the information to which we are entitled when expenditure takes place on such a scale. Above all, more important than the question of what happened to British diplomacy or to British intelligence is what happened to our power to act. The right hon. Lady seemed to dismiss that question. It cannot be dismissed. Of course this country has the power to act—short, often, of taking military measures. Indeed, we have always been told, as I understand it, that the purpose of having some military power is to deter. The right to deter and the capacity to deter were both required in this situation.

The previous Government had to deal with the same kind of dictatorial regime in the Argentine, the same kind of threat to the people of the Falkland Islands, and the same kinds of problems as those with which the Goverment have had to wrestle over the past weeks and months. My right hon. Friend the Member for Cardiff, South-East (Mr. Callaghan) compressed the whole position into the question that he put to the Government only last Tuesday. I shall read his remarks to the House, and I ask the House to mark every word. This was no factious Opposition. This was an Opposition Member seeking to sustain the Government if the Government were doing their duty.

My right hon. Friend said:

"I support the Government's attempts to solve the problem by diplomatic means, which is clearly the best and most sensible way of approaching the problem, but is the Minister aware that there have been other recent occasions when the Argentinians, when beset by internal troubles, have tried the same type of tactical diversion? Is the Minister aware that on a very recent occasion, of which I have full knowledge, Britain assembled ships which had been stationed in the Caribbean, Gibraltar and in the Mediterranean, and stood them about 400 miles off the Falklands in support of HMS "Endurance", and that when this fact became known, without fuss and publicity, a diplomatic solution followed? While I do not press the Minister on what is happening today, I trust that it is the same sort of action."—[Official Report, 30 March 1982; Vol. 21, c. 198.]" The House and whole country have the right to say the same thing to the Government. The people of the Falkland Islands have an even greater right to say it than ourselves. The right hon. Lady has not answered that question. She has hardly attempted to answer it. It is no answer to refer to the matter so effectively disposed of by my hon. Friend the Member for Merthyr Tydfil (Mr. Rowlands), who has much knowledge of these matters. It is, of course, a very different question.

No one can say for certain that the pacific and honourable solution of this problem that was reached in 1977 was due to the combination of diplomatic and military activity. These things cannot be proved. There is, however, every likelihood that that was the case. In any event, the fact that it worked on the previous occasion was surely all the more reason for the Government's seeking to make it work on this occasion, especially when, according to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs—I refer again to the diplomatic exchanges—it had been going on for some time. According to the diplomatic exchanges, the Argentine Government were still awaiting an answer from the Secretary of State on some of the matters involved.

The right hon. Lady made some play, although not very effectively, with the time it takes to get warships into the area. We are talking about events several weeks ago. All these matters have to be answered. They cannot be answered fully in this debate. There will have to be another debate on the subject next week. Whether that debate takes the form of a motion of censure, or some other form, or perhaps takes the form of the establishment of an inquiry into the whole matter, so that all the evidence and the facts can be laid before the people of this country, I have not the slightest doubt that, at some stage, an inquiry of that nature, without any inhibitions and restraints, that can probe the matter fully will have to be undertaken.

I return to what I said at the start of my remarks. We are paramountly concerned, like, I am sure, the bulk of the House—I am sure that the country is also concerned—about what we can do to protect those who rightly and naturally look to us for protection. So far, they have been betrayed. The responsibility for the betrayal rests with the Government. The Government must now prove by deeds—they will never be able to do it by words—that they are not responsible for the betrayal and cannot be faced with that charge. That is the charge, I believe, that lies against them. Even though the position and the circumstances of the people who live in the Falkland Islands are uppermost in our minds—it would be outrageous if that were not the case—there is the longer-term interest to ensure that foul and brutal aggression does not succeed in our world. If it does, there will be a danger not merely to the Falkland Islands, but to people all over this dangerous planet.

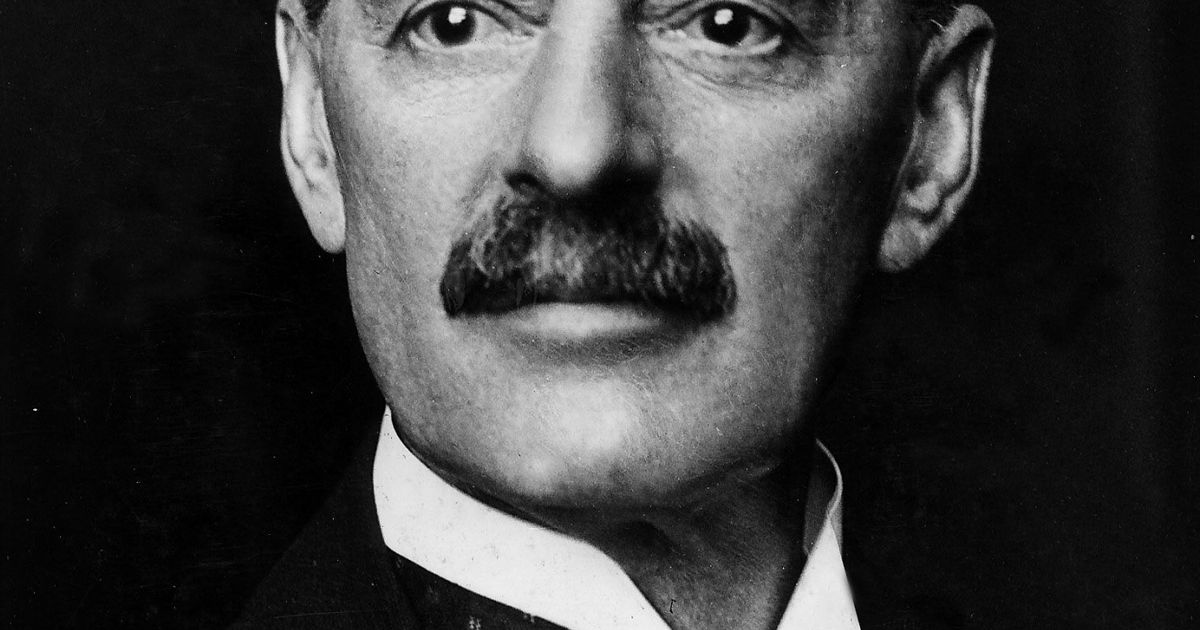

Neville Chamberlain: 'What has become of the assurance "We don't want Czechs in the Reich"?' speech following Hitler's annexation of Czechoslovakia - 1939

17 March 1939, Birmingham, United Kingdom

I had intended to-night to talk to you upon a variety of subjects, upon trade and employment, upon social service, and upon finance. But the tremendous events which have been taking place this week in Europe have thrown everything else into the background, and I feel that what you, and those who are not in this hall but are listening to me, will want to hear is some indication of the views of His Majesty's Government as to the nature and the implications of those events.

One thing is certain. Public opinion in the world has received a sharper shock than has ever yet been administered to it, even by the present regime in Germany. What may be the ultimate effects of this profound disturbance on men's minds cannot yet be foretold, but I am sure that it must be far-reaching in its results upon the future. Last Wednesday we had a debate upon it in the House of Commons. That was the day on which the German troops entered Czecho-Slovakia, and all of us, but particularly the Government, were at a disadvantage because the information that we had was only partial; much of it was unofficial. We had no time to digest it, much less to form a considered opinion upon it. And so it necessarily followed that I, speaking on behalf of the Government, with all the responsibility that attaches to that position, was obliged to confine myself to a very restrained and cautious exposition, on what at the time I felt I could make but little commentary. And, perhaps naturally, that somewhat cool and objective statement gave rise to a misapprehension, and some people thought that because I spoke quietly, because I gave little expression to feeling, therefore my colleagues and I did not feel strongly on the subject. I hope to correct that mistake to-night.

But I want to say something first about an argument which has developed out of these events and which was used in that debate, and has appeared since in various organs of the press. It has been suggested that this occupation of Czecho-Slovakia was the direct consequence of the visit which I paid to Germany last autumn, and that, since the result of these events has been to tear up the settlement that was arrived at at Munich, that proves that the whole circumstances of those visits were wrong. It is said that, as this was the personal policy of the Prime Minister, the blame for the fate of Czecho-Slovakia must rest upon his shoulders. That is an entirely unwarrantable conclusion The facts as they are to-day cannot change the facts as they were last September. If I was right then, I am still right now. Then there are some people who say: "We considered you were wrong in September, and now we have been proved to be right." Let me examine that. When I decided to go to Germany I never expected that I was going to escape criticism. Indeed,; I did not go there to get popularity. I went there first and foremost because, in what appeared to be an almost desperate situation, that seemed to me to offer the only chance of averting a European war. And I might remind you that, when it was first announced that I was going, not a voice was raised in criticism. Everyone applauded that effort. It was only later, when it appeared that the results of the final settlement fell short of the expectations of some who did not fully appreciate the facts-it was only then that the attack began, and even then it was not the visit, it was the terms of settlement that were disapproved.

Well, I have never denied that the terms which I was able to secure at Munich were not those that I myself would have desired. But, as I explained then, I had to deal with no new problem. This was something that had existed ever since the Treaty of Versailles-a problem that ought to have been solved long ago if only the statesmen of the last twenty years had taken broader and more enlightened views of their duty. It had become like a disease which had been long neglected, and a surgical operation was necessary to save the life of the patient.

After all, the first and the most immediate object of my visit was achieved. The peace of Europe was saved; and, if it had not been for those visits, hundreds of thousands of families would to-day have been in mourning for the flower of Europe's best manhood. I would like once again to express my grateful thanks to all those correspondents who have written me from all over the world to express their gratitude and their appreciation of what I did then and of what I have been trying to do since.

Really I have no need to defend my visits to Germany last autumn, for what was the alternative? Nothing that we could have done, nothing that France could have done, or Russia could have done could possibly have saved Czecho-Slovakia from invasion and destruction. Even if we had subsequently gone to war to punish Germany for her actions, and if after the frightful losses which would have been inflicted upon all partakers in the war we had been victorious in the end, never could we have reconstructed Czecho-Slovakia as she was framed by the Treaty of Versailles.

But I had another purpose, too, in going to Munich. That was to further the policy which I have been pursuing ever since I have been in my present position-a policy which is sometimes called European appeasement, although I do not think myself that that is a very happy term or one which accurately describes its purpose. If that policy were to succeed, it was essential that no Power should seek to obtain a general domination of Europe; but that each one should be contented to obtain reasonable facilities for developing its own resources, securing its own share of international trade, and improving the conditions of its own people. I felt that, although that might well mean a clash of interests between different States, nevertheless, by the exercise of mutual goodwill and understanding of what were the limits of the desires of others, it should be possible to resolve all differences by discussion and without armed conflict. I hoped in going to Munich to find out by personal contact what was in Herr Hitler's mind, and whether it was likely that he would be willing to co-operate in a programme of that kind. Well, the atmosphere in which our discussions were conducted was not a very favourable one, because we were in the middle of an acute crisis; but, nevertheless, in the intervals between more official conversations I had some opportunities of talking with him and of hearing his views, and I thought that results were not altogether unsatisfactory. When I came back after my second visit I told the House of Commons of a conversation I had had with Herr Hitler, of which I said that, speaking with great earnestness, he repeated what he had already said at Berchtesgaden-namely, that this was the last of his territorial ambitions in Europe, and that he had no wish to include in the Reich people of other races than German. Herr Hitler himself confirmed this account of the conversation in the speech which he made at the Sportpalast in Berlin, when he said: "This is the last territorial claim which I have to make in Europe." And a little later in the same speech he said: "I have assured Mr. Chamberlain, and I emphasise it now, that when this problem is solved Germany has no more territorial problems in Europe." And he added: "I shall not be interested in the Czech State any more, and I can guarantee it. We don't want any Czechs any more."

And then in the Munich Agreement itself, which bears Herr Hitler's signature, there is this clause: "The final determination of the frontiers will be carried out by the international commission"-the final determination. And, lastly, in that declaration which he and I signed together at Munich, we declared that any other question which might concern our two countries should be dealt with by the method of consultation.

Well, in view of those repeated assurances, given voluntarily to me, I considered myself justified in founding a hope upon them that once this Czecho-Slovakian question was settled, as it seemed at Munich it would be, it would be possible to carry farther that policy of appeasement which I have described. But, notwithstanding, at the same time I was not prepared to relax precautions until I was satisfied that the policy had been established and had been accepted by others, and therefore, after Munich, our defence programme was actually accelerated, and it was expanded so as to remedy certain weaknesses which had become apparent during the crisis. I am convinced that after Munich the great majority of British people shared my hope, and ardently desired that that policy should be carried further. But to-day I share their disappointment, their indignation, that those hopes have been so wantonly shattered.

How can these events this week be reconciled with those assurances which I have read out to you? Surely, as a joint signatory of the Munich Agreement, I was entitled, if Herr Hitler thought it ought to be undone, to that consultation which is provided for in the Munich declaration. Instead of that he has taken the law into his own hands. Before even the Czech President was received, and confronted with demands which he had no power to resist, the German troops were on the move, and within a few hours they were in the Czech capital.

According to the proclamation which was read out in Prague yesterday, Bohemia and Moravia have been annexed to the German Reich. Non-German inhabitants, who, of course, include the Czechs, are placed under the German Protector in the German Protectorate. They are to be subject to the political, military and economic needs of the Reich. They are called self-governing States, but the Reich is to take charge of their foreign policy, their customs and their excise, their bank reserves, and the equipment of the disarmed Czech forces. Perhaps most sinister of all, we hear again of the appearance of the Gestapo, the secret police, followed by the usual tale of wholesale arrests of prominent individuals, with consequences with which we are all familiar.

Every man and woman in this country who remembers the fate of the Jews and the political prisoners in Austria must be filled to-day with distress and foreboding. Who can fail to feel his heart go out in sympathy to the proud and brave people who have so suddenly been subjected to this invasion, whose liberties are curtailed, whose national independence has gone? What has become of this declaration of "No further territorial ambition"? What has become of the assurance "We don't want Czechs in the Reich"? What regard had been paid here to that principle of self-determination on which Herr Hitler argued so vehemently with me at Berchtesgaden when he was asking for the severance of Sudetenland from Czecho-Slovakia and its inclusion in the German Reich?

Now we are told that this seizure of territory has been necessitated by disturbances in Czecho-Slovakia. We are told that the proclamation of this new German Protectorate against the will of its inhabitants has been rendered inevitable by disorders which threatened the peace and security of her mighty neighbour. If there were disorders, were they not fomented from without? And can anybody outside Germany take seriously the idea that they could be a danger to that great country, that they could provide any justification for what has happened?

Does not the question inevitably arise in our minds, if it is so easy to discover good reasons for ignoring assurances so solemnly and so repeatedly given, what reliance can be placed upon any other assurances that come from the same source?

There is another set of questions which almost inevitably must occur in our minds and to the minds of others, perhaps even in Germany herself. Germany, under her present regime, has sprung a series of unpleasant surprises upon the world. The Rhineland, the Austrian Anschluss, the severance of Sudetenland-all these things shocked and affronted public opinion throughout the world. Yet, however much we might take exception to the methods which were adopted in each of those cases, there was something to be said, whether on account of racial affinity or of just claims too long resisted-there was something to be said for the necessity of a change in the existing situation.

But the events which have taken place this week in complete disregard of the principles laid down by the German Government itself seem to fall into a different category, and they must cause us all to be asking ourselves: "Is this the end of an old adventure, or is it the beginning of a new?"

"Is this the last attack upon a small State, or is it to be followed by others? Is this, in fact, a step in the direction of an attempt to dominate the world by force?"

Those are grave and serious questions. I am not going to answer them to-night. But I am sure they will require the grave and serious consideration not only of Germany's neighbours, but of others, perhaps even beyond the confines of Europe. Already there are indications that the process has begun, and it is obvious that it is likely now to be speeded up.

We ourselves will naturally turn first to our partners in the British Commonwealth of Nations and to France, to whom we are so closely bound, and I have no doubt that others, too, knowing that we are not disinterested in what goes on in South-Eastern Europe, will wish to have our counsel and advice.

In our own country we must all review the position with that sense of responsibility which its gravity demands. Nothing must be excluded from that review which bears upon the national safety. Every aspect of our national life must be looked at again from that angle. The Government, as always, must bear the main responsibility, but I know that all individuals will wish to review their own position, too, and to consider again if they have done all they can to offer their service to the State.

I do not believe there is anyone who will question my sincerity when I say there is hardly anything I would not sacrifice for peace. But there is one thing that I must except, and that is the liberty that we have enjoyed for hundreds of years, and which we will never surrender. That I, of all men, should feel called upon to make such a declaration-that is the measure of the extent to which these events have shattered the confidence which was just beginning to show its head and which, if it had been allowed to grow, might have made this year memorable for the return of all Europe to sanity and stability.

It is only six weeks ago that I was speaking in this city, and that I alluded to rumours and suspicions which I said ought to be swept away. I pointed out that any demand to dominate the world by force was one which the democracies must resist, and I added that I could not believe that such a challenge was intended, because no Government with the interests of its own people at heart could expose them for such a claim to the horrors of world war.

And, indeed, with the lessons of history for all to read, it seems incredible that we should see such a challenge. I feel bound to repeat that, while I am not prepared to engage this country by new unspecified commitments operating under conditions which cannot now be foreseen, yet no greater mistake could be made than to suppose that, because it believes war to be a senseless and cruel thing, this nation has so lost its fibre that it will not take part to the utmost of its power in resisting such a challenge if it ever were made. For that declaration I am convinced that I have not merely the support, the sympathy, the confidence of my fellow-countrymen and countrywomen, but I shall have also the approval of the whole British Empire and of all other nations who value peace, indeed, but who value freedom even more.

Adolf Hitler: 'I am from now on just first soldier of the Reich', Declaration of War - 1939

1 September 1939, Reichstag, Berlin, Germany

For months we have been suffering under the torture of a problem which the Versailles Diktat created - a problem which has deteriorated until it becomes intolerable for us. Danzig was and is a German city. The Corridor was and is German. Both these territories owe their cultural development exclusively to the German people. Danzig was separated from us, the Corridor was annexed by Poland. As in other German territories of the East, all German minorities living there have been ill-treated in the most distressing manner. More than 1,000,000 people of German blood had in the years 1919-1920 to leave their homeland.

As always, I attempted to bring about, by the peaceful method of making proposals for revision, an alteration of this intolerable position. It is a lie when the outside world says that we only tried to carry through our revisions by pressure. Fifteen years before the National Socialist Party came to power there was the opportunity of carrying out these revisions by peaceful settlements and understanding. On my own initiative I have, not once but several times, made proposals for the revision of intolerable conditions. All these proposals, as you know, have been rejected - proposals for limitation of armaments and even, if necessary, disarmament, proposals for limitation of warmaking, proposals for the elimination of certain methods of modern warfare. You know the proposals that I have made to fulfill the necessity of restoring German sovereignty over German territories. You know the endless attempts I made for a peaceful clarification and understanding of the problem of Austria, and later of the problem of the Sudetenland, Bohemia, and Moravia. It was all in vain.

It is impossible to demand that an impossible position should be cleared up by peaceful revision and at the same time constantly reject peaceful revision. It is also impossible to say that he who undertakes to carry out these revisions for himself transgresses a law, since the Versailles Diktat is not law to us. A signature was forced out of us with pistols at our head and with the threat of hunger for millions of people. And then this document, with our signature, obtained by force, was proclaimed as a solemn law.

In the same way, I have also tried to solve the problem of Danzig, the Corridor, etc., by proposing a peaceful discussion. That the problems had to be solved was clear. It is quite understandable to us that the time when the problem was to be solved had little interest for the Western Powers. But that time is not a matter of indifference to us. Moreover, it was not and could not be a matter of indifference to those who suffer most.

In my talks with Polish statesmen I discussed the ideas which you recognize from my last speech to the Reichstag. No one could say that this was in any way an inadmissible procedure on undue pressure. I then naturally formulated at last the German proposals, and I must once more repeat that there is nothing more modest or loyal than these proposals. I should like to say this to the world. I alone was in the position to make such proposal, for I know very well that in doing so I brought myself into opposition to millions of Germans. These proposals have been refused. Not only were they answered first with mobilization, but with increased terror and pressure against our German compatriots and with a slow strangling of the Free City of Danzig - economically, politically, and in recent weeks by military and transport means.

Poland has directed its attacks against the Free City of Danzig. Moreover, Poland was not prepared to settle the Corridor question in a reasonable way which would be equitable to both parties, and she did not think of keeping her obligations to minorities.

I must here state something definitely; German has kept these obligations; the minorities who live in Germany are not persecuted. No Frenchman can stand up and say that any Frenchman living in the Saar territory is oppressed, tortured, or deprived of his rights. Nobody can say this.

For four months I have calmly watched developments, although I never ceased to give warnings. In the last few days I have increased these warnings. I informed the Polish Ambassador three weeks ago that if Poland continued to send to Danzig notes in the form of ultimata, and if on the Polish side an end was not put to Customs measures destined to ruin Danzig's trade, then the Reich could not remain inactive. I left no doubt that people who wanted to compare the Germany of to-day with the former Germany would be deceiving themselves.

An attempt was made to justify the oppression of the Germans by claiming that they had committed acts of provocation. I do not know in what these provocations on the part of women and children consist, if they themselves are maltreated, in some cases killed. One thing I do know - that no great Power can with honour long stand by passively and watch such events.

I made one more final effort to accept a proposal for mediation on the part of the British Government. They proposed, not that they themselves should carry on the negotiations, but rather that Poland and Germany should come into direct contact and once more pursue negotiations.

I must declare that I accepted this proposal, and I worked out a basis for these negotiations which are known to you. For two whole days I sat in my Government and waited to see whether it was convenient for the Polish Government to send a plenipotentiary or not. Last night they did not send us a plenipotentiary, but instead informed us through their Ambassador that they were still considering whether and to what extent they were in a position to go into the British proposals. The Polish Government also said that they would inform Britain of their decision.

Deputies, if the German Government and its Leader patiently endured such treatment Germany would deserve only to disappear from the political stage. But I am wrongly judged if my love of peace and my patience are mistaken for weakness or even cowardice. I, therefore, decided last night and informed the British Government that in these circumstances I can no longer find any willingness on the part of the Polish Government to conduct serious negotiations with us.

These proposals for mediation have failed because in the meanwhile there, first of all, came as an answer the sudden Polish general mobilization, followed by more Polish atrocities. These were again repeated last night. Recently in one night there were as many as twenty-one frontier incidents: last night there were fourteen, of which three were quite serious. I have, therefore, resolved to speak to Poland in the same language that Poland for months past has used toward us. This attitude on the part of the Reich will not change.

The other European States understand in part our attitude. I should like here above all to thank Italy, which throughout has supported us, but you will understand that for the carrying on of this struggle we do not intend to appeal to foreign help. We will carry out this task ourselves. The neutral States have assured us of their neutrality, just as we had already guaranteed it to them.

When statesmen in the West declare that this affects their interests, I can only regret such a declaration. It cannot for a moment make me hesitate to fulfill my duty. What more is wanted? I have solemnly assured them, and I repeat it, that we ask nothing of those Western States and never will ask anything. I have declared that the frontier between France and Germany is a final one. I have repeatedly offered friendship and, if necessary, the closest co-operation to Britain, but this cannot be offered from one side only. It must find response on the other side. Germany has no interests in the West, and our western wall is for all time the frontier of the Reich on the west. Moreover, we have no aims of any kind there for the future. With this assurance we are in solemn earnest, and as long as others do not violate their neutrality we will likewise take every care to respect it.

I am happy particularly to be able to tell you of one event. You know that Russia and Germany are governed by two different doctrines. There was only one question that had to be cleared up. Germany has no intention of exporting its doctrine. Given the fact that Soviet Russia has no intention of exporting its doctrine to Germany, I no longer see any reason why we should still oppose one another. On both sides we are clear on that. Any struggle between our people would only be of advantage to others. We have, therefore, resolved to conclude a pact which rules out for ever any use of violence between us. It imposes the obligation on us to consult together in certain European questions. It makes possible for us economic co-operation, and above all it assures that the powers of both these powerful States are not wasted against one another. Every attempt of the West to bring about any change in this will fail.

At the same time I should like here to declare that this political decision means a tremendous departure for the future, and that it is a final one. Russia and Germany fought against one another in the World War. That shall and will not happen a second time. In Moscow, too, this pact was greeted exactly as you greet it. I can only endorse word for word the speech of Russian Foreign Commissar, Molotov.

I am determined to solve (1) the Danzig question; (2) the question of the Corridor; and (3) to see to it that a change is made in the relationship between Germany and Poland that shall ensure a peaceful co-existence. In this I am resolved to continue to fight until either the present Polish government is willing to continue to bring about this change or until another Polish Government is ready to do so. I am resolved t remove from the German frontiers the element of uncertainty, the everlasting atmosphere of conditions resembling civil war. I will see to it that in the East there is, on the frontier, a peace precisely similar to that on our other frontiers.

In this I will take the necessary measures to se that they do not contradict the proposals I have already made known in the Reichstag itself to the rest of the world, that is to say, I will not war against women and children. I have ordered my air force to restrict itself to attacks on military objectives. If, however, the enemy thinks he can form that draw carte blanche on his side to fight by the other methods he will receive an answer that will deprive him of hearing and sight.

This night for the first time Polish regular soldiers fired on our territory. Since 5.45 A.M. we have been returning the fire, and from now on bombs will be met by bombs. Whoever fight with poison gas will be fought with poison gas. Whoever departs from the rules of humane warfare can only expect that we shall do the same. I will continue this struggle, no matter against whom, until the safety of the Reich and its rights are secured.

For six years now I have been working on the building up of the German defenses. Over 90 millions have in that time been spent on the building up of these defense forces. They are now the best equipped and are above all comparison with what they were in 1914. My trust in them is unshakable. When I called up these forces and when I now ask sacrifices of the German people and if necessary every sacrifice, then I have a right to do so, for I also am to-day absolutely ready, just as we were formerly, to make every possible sacrifice.

I am asking of no German man more than I myself was ready throughout four years at any time to do. There will be no hardships for Germans to which I myself will not submit. My whole life henceforth belongs more than ever to my people. I am from now on just first soldier of the German Reich. I have once more put on that coat that was the most sacred and dear to me. I will not take it off again until victory is secured, or I will not survive the outcome.

Should anything happen to me in the struggle then my first successor is Party Comrade Goring; should anything happen to Party Comrade Goring my next successor is Party Comrade Hess. You would then be under obligation to give to them as Fuhrer the same blind loyalty and obedience as to myself. Should anything happen to Party Comrade Hess, then by law the Senate will be called, and will choose from its midst the most worthy - that is to say the bravest - successor.

As a National Socialist and as German soldier I enter upon this struggle with a stout heart. My whole life has been nothing but one long struggle for my people, for its restoration, and for Germany. There was only one watchword for that struggle: faith in this people. One word I have never learned: that is, surrender.

If, however, anyone thinks that we are facing a hard time, I should ask him to remember that once a Prussian King, with a ridiculously small State, opposed a stronger coalition, and in three wars finally came out successful because that State had that stout heart that we need in these times. I would, therefore, like to assure all the world that a November 1918 will never be repeated in German history. Just as I myself am ready at any time to stake my life - anyone can take it for my people and for Germany - so I ask the same of all others.

Whoever, however, thinks he can oppose this national command, whether directly of indirectly, shall fall. We have nothing to do with traitors. We are all faithful to our old principle. It is quite unimportant whether we ourselves live, but it is essential that our people shall live, that Germany shall live. The sacrifice that is demanded of us is not greater than the sacrifice that many generations have made. If we form a community closely bound together by vows, ready for anything, resolved never to surrender, then our will will master every hardship and difficulty. And I would like to close with the declaration that I once made when I began the struggle for power in the Reich. I then said: "If our will is so strong that no hardship and suffering can subdue it, then our will and our German might shall prevail."

Adolf Hitler: 'My patience is now at an end', speech demanding Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia - 1938

26 September 1938, Berlin, Germany

I have really in these years pursued a practical peace policy. I have approached all apparently impossible problems with the firm resolve to solve them peacefully even when there was the danger of making more or less serious renunciations on Germany’s part. I myself am a front-line soldier and I know how grave a thing war is. I wanted to spare the German people such an evil. Problem after problem I have tackled with the set purpose to make every effort to render possible a peaceful solution.

The most difficult problem which faced me was the relation between Germany and Poland. There was a danger that the conception of a ‘heredity enmity’ might take possession of our people and of the Polish people. That I wanted to prevent.

I know quite well that I should not have succeeded if Poland at that time had had a democratic constitution. For these democracies which are overflowing with phrases about peace are the most bloodthirsty instigators of war. But Poland at that time was governed by no democracy but by a man. In the course of barely a year it was possible to conclude an agreement which, in the first instance for a period of ten years, on principle removed the danger of a conflict. We are all convinced that this agreement will bring with it a permanent pacification. We realize that here are two peoples which must live side by side and that neither of them can destroy the other. A state with a population of thirty-three millions will always strive for an access to the sea. A way to an understanding had therefore to be found ….

‘He will either accept this offer and now at last give to the Germans their freedom, or we will go and fetch this freedom for ourselves.’

And now before us stands the last problem that must be solved and will be solved. It is the last territorial claim which I have to make in Europe, but it is the claim from which I will not recede and which, God willing, I will make good ….

I have only a few statements still to make. I am grateful to Mr Chamberlain for all his efforts. I have assured him that the German people desires nothing else than peace, but I have also told him that I cannot go back behind the limits set to our patience. I have further assured him, and I repeat it here, that when this problem is solved there is for Germany no further territorial problem in Europe.

And I have further assured him that at the moment when Czechoslovakia solves her problems, that means when the Czechs have come to terms with their other minorities, and that peaceably and not through oppression, then I have no further interest in the Czech state. And that is guaranteed to him! We want no Czechs!

But in the same way I desire to state before the German people that with regard to the problem of the Sudeten Germans my patience is now at an end! I have made Mr Benes an offer which is nothing but the carrying into effect of what he himself has promised. The decision now lies in his hands: peace or war. He will either accept this offer and now at last give to the Germans their freedom or we will go and fetch this freedom for ourselves.

On 1 September 1939, Hitler announced to the Reichstag his intention to invade Poland, knowing that this action would bring a declaration of war from Britain and France. In justification, he referred to the terms of the Versailles Treaty and duplicitouslt insisted he had no intention of invading countries to the west of Germany: ‘I have declared that the frontier between France and Germany is a final one.’ Nine rnonths later, German troops had occupied Holland, Belgium and France and Britain was facing the threat of invasion. Even during the war, German industry flourished and productivity increased, helped by slave labour drawn from the occupied territories, including those beyond the ‘western wall’.

I have declared that the frontier between France and Germany is a final one have repeatedly offered friendship and, if necessary, the closest cooperation Britain, but this cannot be offered from one side only. It must find response the other side. Germany has no interests in the West, and our western wall all time the frontier of the Reich on the west. Moreover, we have no aims kind there for the future. With this assurance we are in solemn earnest, and long as others do not violate their neutrality we will likewise take every care to respect it.

‘Germany has no interests in the West, and our western wall is for all· time the frontier of the Reich on the west.’

I am happy particularly to be able to tell you of one event. You know that Russia and Germany are governed by two different doctrines. There was only one question that had to be cleared up. Germany has no intention of exporting its doctrine. Given the fact that Soviet Russia has no intention of exporting its doctrine to Germany, I no longer see any reason why we should still oppose another. On both sides we are clear on that. Any struggle between our people would only be of advantage to others. We have, therefore, resolved to conclude a pact which rules out for ever any use of violence between us. It imposes the obligation on us to consult together in certain European questions. It maker possible for us economic cooperation, and above all it assures that the power both these powerful states are not wasted against one another. Every attend the West to bring about any change in this will fail.

At the same time I should like here to declare that this political decision means a tremendous departure for the future, and that it is a final one. Russia and Germany fought against one another in the World War. That shall and will not happen a second time. In Moscow, too, this pact was greeted exactly as you greet it. I can only endorse word for word the speech of the Russian Foreign Commissar, Molotov.

‘My whole life has been nothing but one long struggle for my people.’

I am determined to solve the Danzig question; the question of the Corridor and to see to it that a change is made in the relationship between Germany and Poland that shall ensure a peaceful co-existence. In this I am resolved to continue to fight until either the present Polish government is willing to bring about this change or until another Polish government is ready to do so. I am resolved to remove from the German frontiers the element of uncertainty, the everlasting atmosphere of conditions resembling civil war. I will see to it that in the East there is, on the frontier, a peace precisely similar to that on our other frontiers.

In this I will take the necessary measures to see that they do not contradict the proposals I have already made known in the Reichstag itself to the rest of the world, that is to say, I will not war against women and children. I have ordered my air force to restrict itself to attacks on military objectives. If, however, the enemy thinks he can from that draw carte blanche on his side to fight by the other methods he will receive an answer that will deprive him of hearing and sight.

This night for the first time Polish regular soldiers fired on our own territory.

Since 5.45 am we have been returning the fire, and from now on bombs will be met with bombs. Whoever fights with poison gas will be fought with poison gas.

Whoever departs from the rules of humane warfare can only expect that we shall do the same. I will continue this struggle, no matter against whom, until the safety of the Reich and its rights are secured.

For six years now I have been working on the building up of the German defences.

Over 90 milliards have in that time been spent on the building up of these defence forces. They are now the best equipped and are above all comparison with what they were in 1914. My trust in them is unshakeable. When I called up these forces and when I now ask sacrifices of the German people and if necessary every sacrifice, then I have a right to do so, for I also am today absolutely ready, just as we were formerly, to make every personal sacrifice.

‘A November 19 18 will never be repeated In German history.’

I am asking of no German man more than I myself was ready throughout four years at any time to do. There will be no hardships for Germans to which I myself will not submit. My whole life henceforth belongs more than ever to my people.

I am from now on just first soldier of the German Reich. I have once more put on that coat that was the most sacred and dear to me. I will not take it off again until victory is secured, or I will not survive the outcome.

As a National Socialist and as a German soldier I enter upon this struggle with a stout heart. My whole life has been nothing but one long struggle for my people, for its restoration, and for Germany. There was only one watchword for that struggle: faith in this people. One word I have never learned: that is, surrender.

If, however, anyone thinks that we are facing a hard time, I should ask him to remember that once a Prussian king, with a ridiculously small state, opposed a stronger coalition, and in three wars finally came out successful because that state had that stout heart that we need in these times. I would, therefore, like to assure all the world that a November 1918 will never be repeated in German history. Just as I myself am ready at any time to stake my life – anyone can take it for my people and for Germany – so I ask the same of all others.

Whoever, however, thinks he can oppose this national command, whether directly or indirectly, shall fall. We have nothing to do with traitors. We are all faithful to our old principle. It is quite unimportant whether we ourselves live, but it is essential that our people shall live, that Germany shall live. The sacrifice that is demanded of us is not greater than the sacrifice that many generations have made. If we form a community closely bound together by vows, ready for anything, resolved never to surrender, then our will will master every hardship and difficulty. And I would like to close with the declaration that lance made when I began the struggle for power in the Reich. I then said: ‘If our will is so strong that no hardship and suffering can subdue it, then our will and our German might shall prevail.’

Geroge VI: 'For the second time in the lives of most of us, we are at war', broadcast to the Empire - 1939

3 September, 1939, London, United Kingdom

This speech is a feature in the movie 'The King's Speech'. It was delivered with His Majesty's Australian speech therapist, Lionel Logue, in the room.

In this grave hour, perhaps the most fateful in our history, I send to every household of my peoples, both at home and overseas, this message, spoken with the same depth of feeling for each one of you as if I were able to cross your threshold and speak to you myself.

For the second time in the lives of most of us, we are at war.

Over and over again, we have tried to find a peaceful way out of the differences between ourselves and those who are now our enemies; but it has been in vain.

We have been forced into a conflict, for we are called, with our allies, to meet the challenge of a principle which, if it were to prevail, would be fatal to any civilized order in the world.

It is a principle which permits a state, in the selfish pursuit of power, to disregard its treaties and its solemn pledges, which sanctions the use of force or threat of force against the sovereignty and independence of other states.

Such a principle, stripped of all disguise, is surely the mere primitive doctrine that might is right, and if this principle were established through the world, the freedom of our own country and of the whole British Commonwealth of nations would be in danger.

But far more than this, the peoples of the world would be kept in bondage of fear, and all hopes of settled peace and of the security, of justice and liberty, among nations, would be ended.

This is the ultimate issue which confronts us. For the sake of all that we ourselves hold dear, and of the world order and peace, it is unthinkable that we should refuse to meet the challenge.

It is to this high purpose that I now call my people at home, and my peoples across the seas, who will make our cause their own.

I ask them to stand calm and firm and united in this time of trial.

The task will be hard. There may be dark days ahead, and war can no longer be confined to the battlefield, but we can only do the right as we see the right, and reverently commit our cause to God. If one and all we keep resolutely faithful to it, ready for whatever service or sacrifice it may demand, then with God's help, we shall prevail.

May He bless and keep us all.

Neville Chamberlain: 'May He defend the right. It is the evil things that we shall be fighting against', Declaration of War - 1939

3 September, 1939, national BBC broadcast, London, United Kingdom

This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a

final Note stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o'clock that they were

prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would

exist between us.

I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that

consequently this country is at war with Germany.

You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me that all my long struggle to win

peace has failed. Yet I cannot believe that there is anything more or anything

different that I could have done and that would have been more successful.

Up to the very last it would have been quite possible to have arranged a peaceful

and honourable settlement between Germany and Poland, but Hitler would not have it.

He had evidently made up his mind to attack Poland whatever happened, and

although He now says he put forward reasonable proposals which were rejected by

the Poles, that is not a true statement. The proposals were never shown to the

Poles, nor to us, and, although they were announced in a German broadcast on

Thursday night, Hitler did not wait to hear comments on them, but ordered his

troops to cross the Polish frontier. His action shows convincingly that there is

no chance of expecting that this man will ever give up his practice of using force

to gain his will. He can only be stopped by force.

We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of

Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her

people. We have a clear conscience. We have done all that any country could do to

establish peace. The situation in which no word given by Germany's ruler could be

trusted and no people or country could feel themselves safe has become intolerable.

And now that we have resolved to finish it, I know that you will all play your part

with calmness and courage.

At such a moment as this the assurances of support that we have received from the

Empire are a source of profound encouragement to us.

The Government have made plans under which it will be possible to carry on the

work of the nation in the days of stress and strain that may be ahead. But these

plans need your help. You may be taking your part in the fighting services or as

a volunteer in one of the branches of Civil Defence. If so you will report for

duty in accordance with the instructions you have received. You may be engaged in

work essential to the prosecution of war for the maintenance of the life of the

people - in factories, in transport, in public utility concerns, or in the supply

of other necessaries of life. If so, it is of vital importance that you should

carry on with your jobs.

Now may God bless you all. May He defend the right. It is the evil things that we

shall be fighting against - brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and

persecution - and against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

Franklin Roosevelt: 'A date which will live in infamy', Pearl Harbour attack - 1941

8 December 1941, Address to Joint Houses, Congress, Washington DC, USA

Mr. Vice President, Mr. Speaker, Members of the Senate, and of the House of Representatives:

Yesterday, December 7th, 1941 -- a date which will live in infamy -- the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific.

Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in the American island of Oahu, the Japanese ambassador to the United States and his colleague delivered to our Secretary of State a formal reply to a recent American message. And while this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or of armed attack.

It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time, the Japanese government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace.

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. I regret to tell you that very many American lives have been lost. In addition, American ships have been reported torpedoed on the high seas between San Francisco and Honolulu.

Yesterday, the Japanese government also launched an attack against Malaya.

Last night, Japanese forces attacked Hong Kong.

Last night, Japanese forces attacked Guam.

Last night, Japanese forces attacked the Philippine Islands.

Last night, the Japanese attacked Wake Island.

And this morning, the Japanese attacked Midway Island.