4 July 1948, address to the nation, London, United Kingdom

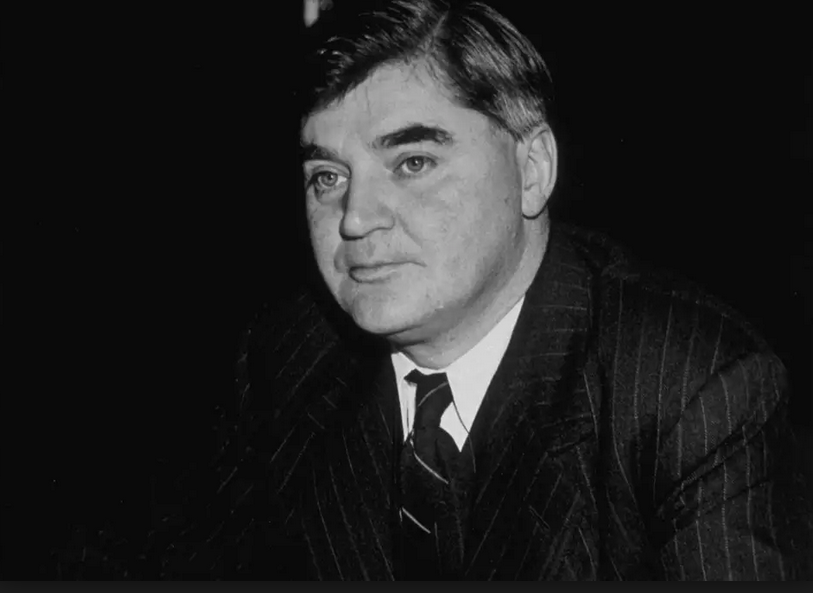

Aneurin (Nye) Bevan: 'I refuse to accept the insurance principle', Speech about NHS -

if anyone knows date and location of this speech, please let us know

I'm proud about the National Health Service. It's a piece of real socialism. It's a piece of real Christianity too, you know.

We had to wait a long time for it.

What I had in mind when we organised the National Health Service in 1946 to 1958. And remember when we did it, you know, you younger ones - this was immediately after the Second World War, when we were as Sir Winston Churchill said, a bankrupt nation. But nevertheless, we did these things. And there's nowhere in any nation in the world, communist or capitalist, any health service to compare with it.

Now, the National Health Service had two main principles:

That the medical arts of science and healing should be made available to people when they needed them, irrespective of whether they could afford to pay for them or not. That was the first principle.

The second principle was that this should be done, not at the expense of the poorer members of the community, but of the well to do.

In short, I refuse to accept the insurance principle. I refuse to accept that the National Health service should be paid for by contributions. I refuse to accept that. I refused to accept it because I thought it was nonsense. If you hadn't fully paid up, you couldn't have a second class operation because your card wasn't full of stamps, could you?

Aneurin (Nye) Bevan: 'It will place this country in the forefront of all countries of the world in medical services?' NHS Bill, second reading - 1946

30 April 1946. Westminster, United Kingdom

I beg to move that the Bill be now read a Second time.

In the last two years there has been such a clamour from sectional interests in the field of national health that we are in danger of forgetting why these proposals are brought forward at all. It is, therefore, very welcome to me – and I am quite certain to hon. Members in all parts of the House – that consideration should now be given, not to this or that sectional interest, but to the requirements of the British people as a whole. The scheme which anyone must draw up dealing with national health must necessarily be conditioned and limited by the evils it is intended to remove. Many of those who have drawn up paper plans for the health services appear to have followed the dictates of abstract principles, and not the concrete requirements of the actual situation as it exists. They drew up all sorts of tidy schemes on paper, which would be quite inoperable in practice.

The first reason why a health scheme of this sort is necessary at all is because it has been the firm conclusion of all parties that money ought not to be permitted to stand in the way of obtaining an efficient health service. Although it is true that the national health insurance system provides a general practitioner service and caters for something like 21 million of the population, the rest of the population have to pay whenever they desire the services of a doctor. It is cardinal to a proper health organisation that a person ought not to be financially deterred from seeking medical assistance at the earliest possible stage. It is one of the evils of having to buy medical advice that, in addition to the natural anxiety that may arise because people do not like to hear unpleasant things about themselves, and therefore tend to postpone consultation as long as possible, there is the financial anxiety caused by having to pay doctors’ bills. Therefore, the first evil that we must deal with is that which exists as a consequence of the fact that the whole thing is the wrong way round. A person ought to be able to receive medical and hospital help without being involved in financial anxiety.

In the second place, the national health insurance scheme does not provide for the self-employed, nor, of course, for the families of dependants. It depends on insurance qualification, and no matter how ill you are, if you cease to be insured you cease to have free doctoring. Furthermore, it gives no backing to the doctor in the form of specialist services. The doctor has to provide himself, he has to use his own discretion and his own personal connections, in order to obtain hospital treatment for his patients and in order to get them specialists, and in very many cases, of course – in an overwhelming number of cases – the services of a specialist are not available to poor people.

Not only is this the case, but our hospital organisation has grown up with no plan, with no system; it is unevenly distributed over the country and indeed it is one of the tragedies of the situation, that very often the best hospital facilities are available where they are least needed. In the older industrial districts of Great Britain hospital facilities are inadequate. Many of the hospitals are too small – very much too small. About 70 per cent. have less than 100 beds, and over 30 per cent. have less than 30. No one can possibly pretend that hospitals so small can provide general hospital treatment. There is a tendency in some quarters to defend the very small hospital on the ground of its localism and intimacy, and for other rather imponderable reasons of that sort, but everybody knows today that if a hospital is to be efficient it must provide a number of specialised services. Although I am not myself a devotee of bigness for bigness sake, I would rather be kept alive in the efficient if cold altruism of a large hospital than expire in a gush of warm sympathy in a small one.

In addition to these defects, the health of the people of Britain is not properly looked after in one or two other respects. The condition of the teeth of the people of Britain is a national reproach. As a consequence of dental treatment having to be bought, it has not been demanded on a scale to stimulate the creation of sufficient dentists, and in consequence there is a woeful shortage of dentists at the present time. Furthermore, about 25 per cent. of the people of Great Britain can obtain their spectacles and get their eyes tested and seen to by means of the assistance given by the approved societies, but the general mass of the people have not such facilities. Another of the evils from which this country suffers is the fact that sufficient attention has not been given to deafness, and hardly any attention has been given so far to the provision of cheap hearing aids and their proper maintenance. I hope to be able to make very shortly a welcome announcement on this question.

One added disability from which our health system suffers is the isolation of mental health from the rest of the health services. Although the present Bill does not rewrite the Lunacy Acts – we shall have to come to that later on – nevertheless, it does, for the first time, bring mental health into the general system of health services. It ought to be possible, and this should be one of the objectives of any civilised health service, for a person who feels mental distress, or who fears that he is liable to become unbalanced in any way to go to a general hospital to get advice and assistance, so that the condition may not develop into a more serious stage. All these disabilities our health system suffers from at the present time, and one of the first merits of this Bill is that it provides a universal health service without any insurance qualifications of any sort. It is available to the whole population, and not only is it available to the whole population freely, but it is intended, through the health service, to generalise the best health advice and treatment. It is intended that there shall be no limitation on the kind of assistance given – the general practitioner service, the specialist, the hospitals, eye treatment, spectacles, dental treatment, hearing facilities, all these are to be made available free.

There will be some limitations for a while, because we are short of many things. We have not enough dentists and it will therefore be necessary for us, in the meantime, to give priority treatment to certain classes – expectant and nursing mothers, children, school children in particular and later on we hope adolescents, Finally we trust that we shall be able to build up a dental service for the whole population. We are short of nurses and we are short, of course, of hospital accommodation, and so it will be some time before the Bill can fructify fully in effective universal service. Nevertheless, it is the object of the Bill, and of the scheme, to provide this as soon as possible, and to provide it universally.

Specialists will be available not only at institutions but for domiciliary visits when needed. Hon. Members in all parts of the House know from their own experience that very many people have suffered unnecessarily because the family has not had the financial resources to call in skilled people. The specialist services, therefore, will not only be available at the hospitals, but will be at the back of the general practitioner should he need them. The practical difficulties of carrying out all these principles and services are very great . When I approached this problem, I made up my mind that I was not going to permit any sectional or vested interests to stand in the way of providing this very valuable service for the British people.

There are, of course, three main instruments through which it is intended that the Health Bill should be worked. There are the hospitals; there are the general practitioners; and there are the health centres. The hospitals are in many ways the vertebrae of the health system, and I first examined what to do with the hospitals. The voluntary hospitals of Great Britain have done invaluable work. When hospitals could not be provided by any other means, they came along. The voluntary hospital system of this country has a long history of devotion and sacrifice behind it, and it would be a most frivolously minded man who would denigrate in any way the immense services the voluntary hospitals have rendered to this country. But they have been established often by the caprice of private charity. They bear no relationship to each other. Two hospitals close together often try to provide the same specialist services unnecessarily, while other areas have not that kind of specialist service at all. They are, as I said earlier, badly distributed throughout the country. It is unfortunate that often endowments are left to finance hospitals in those parts of the country where the well-to-do live while, in very many other of our industrial and rural districts there is inadequate hospital accommodation. These voluntary hospitals are, very many of them, far too small and, therefore, to leave them as independent units is quite impracticable.

Furthermore – I want to be quite frank with the House – I believe it is repugnant to a civilised community for hospitals to have to rely upon private charity. I believe we ought to have left hospital flag days behind. I have always felt a shudder of repulsion when I have seen nurses and sisters who ought to be at their work, and students who ought to be at their work, going about the streets collecting money for the hospitals. I do not believe there is an hon. Member of this House who approves that system. It is repugnant, and we must leave it behind – entirely. But the implications of doing this are very considerable.

I have been forming some estimates of what might happen to voluntary hospital finance when the all-in insurance contributions fall to be paid by the people of Great Britain, when the Bill is passed and becomes an Act, and they are entitled to free hospital services. The estimates I have go to show that between 80 per cent. and 90 per cent. of the revenues of the voluntary hospitals in these circumstances will be provided by public funds, by national or rate funds. And, of course, as the hon. Member reminds me, in very many parts of the country it is a travesty to call them voluntary hospitals. In the mining districts, in the textile districts, in the districts where there are heavy industries it is the industrial population who pay the weekly contributions for the maintenance of the hospitals. When I was a miner I used to find that situation, when I was on the hospital committee. We had an annual meeting and a cordial vote of thanks was moved and passed with great enthusiasm to the managing director of the colliery company for his generosity towards the hospital; and when I looked at the balance sheet, I saw that 97.5 per cent. of the revenues were provided by the miners’ own contributions; but nobody passed a vote of thanks to the miners.

I can assure the hon. and gallant Member that I was no more silent then than I am now. But, of course, it is a misuse of language to call these ‘Voluntary hospitals.” They are not maintained by legally enforced contributions; but, mainly, the workers pay for them because they know they will need the hospitals, and they are afraid of what they would have to pay if they did not provide them. So it is, I say, an impossible situation for the State to find something like 90 per cent of the revenues of these hospitals and still to call them “voluntary.’ So I decided, for this and other reasons, that the voluntary hospitals must be taken over.

I knew very well when I decided this that it would give rise to very considerable resentment in many quarters, but, quite frankly, I am not concerned about the voluntary hospitals’ authorities: I am concerned with the people whom the hospitals are supposed to serve. Every investigation which has been made into this problem has established that the proper hospital unit has to comprise about 1,000 beds – not in the same building but, nevertheless, the general and specialist hospital services can be provided only in a group of that size. This means that a number of hospitals have to be pooled, linked together, in order to provide a unit of that sort. This cannot be done effectively if each hospital is a separate, autonomous body. It is proposed that each of these groups should have a large general hospital, providing general hospital facilities and services, and that there should be a group round it of small feeder hospitals. Many of the cottage hospitals strive to give services that they are not able to give. It very often happens that a cottage hospital harbours ambitions to the hurt of the patients, because they strive to reach a status that they never can reach. In these circumstances, the welfare of the patients is sacrificed to the vaulting ambitions of those in charge of the hospital. If, therefore, these voluntary hospitals are to be grouped in this way, it is necessary that they should submit themselves to proper organisation, and that submission, in our experience, is impracticable if the hospitals, all of them, remain under separate management.

Now, this decision to take over the voluntary hospitals meant, that I then had to decide to whom to give them. Who was to be the receiver? So I turned to an examination of the local government hospital system. Many of the local authorities in Great Britain have never been able to exercise their hospital powers. They are too poor. They are too small. Furthermore, the local authorities of Great Britain inherited their hospitals from the Poor Law, and some of them are monstrous buildings, a cross between a workhouse and a barracks – or a prison. The local authorities are helpless in these matters. They have not been able to afford much money. Some local authorities are first-class. Some of the best hospitals in this country are local government hospitals. But, when I considered what to do with the voluntary hospitals when they had been taken over, and who was to receive them I had to reject the local government unit, because the local authority area is no more an effective gathering ground for the patients of the hospitals than the voluntary hospitals themselves. My hon. Friend said that some of them are too small, and some of them too large. London is an example of being too small and too large at the same time.

It is quite impossible, therefore, to hand over the voluntary hospitals to the local authorities. Furthermore – and this is an argument of the utmost importance – if it be our contract with the British people, if it be our intention that we should universalise the best, that we shall promise every citizen in this country the same standard of service, how can that be articulated through a rate-borne institution which means that the poor authority will not be able to carry out the same thing at all- It means that once more we shall be faced with all kinds of anomalies, just in those areas where hospital facilities are most needed, and in those very conditions where the mass of the poor people will be unable to find the finance to supply the hospitals. Therefore, for reasons which must be obvious – because the local authorities are too small, because their financial capacities are unevenly distributed – I decided that local authorities could not be effective hospital administration units. There are, of course, a large number of hospitals in addition to the general hospitals which the local authorities possess. Tuberculosis sanatoria, isolation hospitals, infirmaries of various kinds, rehabilitation, and all kinds of other hospitals are all necessary in a general hospital service. So I decided that the only thing to do was to create an entirely new hospital service, to take over the voluntary hospitals, and to take over the local government hospitals and to organise them as a single hospital service. If we are to carry out our obligation and to provide the people of Great Britain, no matter where they may be, with the same level of service, then the nation itself will have to carry the expenditure, and cannot put it upon the shoulders of any other authority.

A number of investigations have been made into this subject from time to time, and the conclusion has always been reached that the effective hospital unit should be associated with the medical school. If you grouped the hospitals in about 16 to 20 regions around the medical schools, you would then have within those regions the wide range of disease and disability which would provide the basis for your specialised hospital service. Furthermore, by grouping hospitals around the medical schools, we should be providing what is very badly wanted, and that is a means by which the general practitioners are kept in more intimate association with new medical thought and training. One of the disabilities, one of the shortcomings of our existing medical service, is the intellectual isolation of the general practitioners in many parts of the country. The general practitioner, quite often, practises in loneliness and does not come into sufficiently intimate association with his fellow craftsmen and has not the stimulus of that association, and in consequence of that the general practitioners have not got access to the new medical knowledge in a proper fashion. By this association of the general practitioner with the medical schools through the regional hospital organisation, it will be possible to refresh and replenish the fund of knowledge at the disposal of the general practitioner.

This has always been advised as the best solution of the difficulty. It has this great advantage to which I call the close attention of hon. Members. It means that the bodies carrying out the hospital services of the country are, at the same time, the planners of the hospital service. One of the defects of the other scheme is that the planning authority and executive authority are different. The result is that you get paper planning or bad execution. By making the regional board and regional organisation responsible both for the planning and the administration of the plans, we get a better result, and we get from time to time, adaptation of the plans by the persons accumulating the experience in the course of their administration. The other solutions to this problem which I have looked at all mean that you have an advisory body of planners in the background who are not able themselves to accumulate the experience necessary to make good planners. The regional hospital organisation is the authority with which the specialised services are to be associated, because, as I have explained, this specialised service can be made available for an area of that size, and cannot be made available over a small area.

When we come to an examination of this in Committee, I daresay there will be different points of view about the constitution of the regional boards. It is not intended that the regional boards should be conferences of persons representing different interests and different organisations. If we do that, the regional boards will not be able to achieve reasonable and efficient homogeneity. It is intended that they should be drawn from members of the profession, from the health authorities in the area, from the medical schools and from those who have long experience in voluntary hospital administration. While leaving ourselves open to take the best sort of .individuals on these hospital boards which we can find, we hope before very long to build up a high tradition of hospital administration in the boards themselves. Any system which made the boards conferences, any proposal which made the members delegates, would at once throw the hospital administration into chaos. Although I am perfectly prepared and shall be happy to cooperate with hon. Members in all parts of the House in discussing how the boards should be constituted, I hope I shall not be pressed to make these regional boards merely representative of different interests and different areas. The general hospital administration, therefore, centres in that way.

When we come to the general practitioners we are, of course, in an entirely different field. The proposal which I have made is that the ‘general practitioner shall not be in direct contract with the Ministry of Health, but in contract with new bodies. There exists in the medical ,profession a great resistance to coming under the authority of local government – a great resistance, with which I, to some extent, sympathise. There is a feeling in the medical profession that the general practitioner would be liable to come too much under the medical officer of health, who is the administrative doctor. This proposal does not put the doctor under the local authority; it puts the doctor in contract with an entirely new body – the local executive :council, coterminous with the local health area, county or county borough. On that executive council, the dentists, doctors and chemists will have half the representation. In fact, the whole scheme provides a greater degree of professional representation for the medical profession than any other scheme I have seen.

I have been criticised in some quarters for doing that. I will give the answer now: I have never believed that the demands of a democracy are necessarily satisfied merely by the opportunity of putting a cross against someone’s name every four or five years. I believe that democracy exists in the active participation in administration and policy. Therefore, I believe that it is a wise thing to give the doctors full participation in the administration of their own profession. They must of course, necessarily be subordinated to lay control – we do not want the opposite danger of syndicalism. Therefore, the communal interests must always be safeguarded in this administration. The doctors will be in contract with an executive body of this sort. One of the advantages of that proposal is that the doctors do not become – as some of them have so wildly stated – civil servants. Indeed, one of the advantages of the scheme is that it does not create an additional civil servant.

It imposes no constitutional disability upon any person whatsoever. Indeed, by taking the hospitals from the local authorities and putting them under the regional boards, large numbers of people will be enfranchised who are now disfranchised from participation in local government. So far from this being a huge bureaucracy with all the doctors little civil servants – the slaves of the Minister of Health, as I have seen it described – instead of that, the doctors are under contract with bodies which are not under the local authority, and which are, at the same time, ever open to their own influence and control.

One of the chief problems that I was up against in considering this scheme was the distribution of the general practitioner service throughout the country. The distribution, at the moment, is most uneven. In South Shields before the war there were 4,100 persons per doctor; in Bath 1,590; in Dartford nearly 3,000 and in Bromley 1,620; in Swindon 3,100; in Hastings under 1,200. That distribution of general practitioners throughout the country is most hurtful to the health of our people. It is entirely unfair, and, therefore, if the health services are to be carried out, there must be brought about a redistribution of the general practitioners throughout the country.

Indeed, I could amplify those figures a good deal, but I do not want to weary the House, as Ihave a great deal to say. It was, therefore, decided that there must be redistribution. One of the first consequences of that decision was the abolition of the sale and purchase of practices. If we are to get the doctors where we need them, we cannot possibly allow a new doctor to go in because he has bought somebody’s practice. Proper distribution kills by itself the sale and purchase of practices. I know that there is some opposition to this, and I will deal with that opposition. I have always regarded the sale and purchase of medical practices as an evil in itself. It is tantamount to the sate and purchase of patients. Indeed, every argument advanced about the value of the practice is itself an argument against freedom of choice, because the assumption underlying the high value of a practice is that the patient passes from the old doctor to the new. If they did not pass there would be no value in it. I would like, therefore, to point out to the medical profession that every time they argue for high compensation for the loss of the value of their practices, it is an argument against the free choice which they claim. However, the decision to bring about the proper distribution of general practitioners throughout the country meant that the value of the practices was destroyed. We had, therefore, to consider compensation.

I have never admitted the legal claim, but I admit at once that very real hardship would be inflicted upon doctors if there were no compensation. Many of these doctors look forward to the value of their practices for their retirement. Many of them have had to borrow money to buy practices and, therefore, it would, I think, be inhuman, and certainly most unjust, if no compensation were paid for the value of the practices destroyed. The sum of £66,000,000 is very large. In fact, I think that everyone will admit that the doctors are being treated very generously. However, it is not all loss, because if we had, in providing superannuation, given credit for back service, as we should have had to do, it would have cost £35 million. Furthermore, the compensation will fall to be paid to the dependants when the doctor dies, or when he retires, and so it is spread over a considerable number of years. This global sum has been arrived at by the actuaries and over the figure, I am afraid, we have not had very much control, because the actuaries have agreed it. But the profession itself will be asked to advise as to its distribution among the claimants, because we are interested in the global sum, and the profession, of course, is interested in the equitable distribution of the fund to the claimants.

The doctors claim that the proposals of the Bill amount to direction – not all the doctors say this but some of them do. There is no direction involved at all. When the Measure starts to operate, the doctors in a particular area will be able to enter the public service in that area. A doctor newly coming along would apply to the local executive council for permission to practise in a particular area. His application would then be re-referred to the Medical Practices Committee. The Medical Practices Committee, which is mainly a professional body, would have before it the question of whether there were sufficient general practitioners in that area. If there were enough, the committee would refuse to permit the appointment. No one can really argue that that is direction, because no profession should be allowed to enter the public service in a place where it is not needed. By that method of negative control over a number of years, we hope to bring about over the country a positive redistribution of the general practitioner service. It will not affect the existing situation, because doctors will be able to practise under the new service in the areas to which they belong, but a new doctor, as he comes on, will have to find his practice in a place inadequately served.

I cannot, at the moment, explain to the House what are going to be the rates of remuneration of doctors. The Spens Committee report is not fully available. I hope it will be out next week. I had hoped that it would be ready for this Debate, because this is an extremely important part of the subject, but I have not been able to get the full report. Therefore, it is not possible to deal with remuneration. However, it is possible to deal with some of the principles underlying the remuneration of general practitioners. Some of my hon. Friends on this side of the House are in favour of a full salaried service. I am not. I do not believe that the medical profession is ripe for it, and I cannot dispense with the principle that the payment of a doctor must in some degree be a reward for zeal, and there must be some degree of punishment for lack of it. Therefore, it is proposed that capitation should remain the main source from which a doctor will obtain his remuneration. But it is proposed that there shall be a basic salary and that for a number of very cogent reasons. One is that a young doctor entering practice for the first time needs to be kept alive while he is building up his lists. The present system by which a young man gets a load of debt around his neck in order to practise is an altogether evil one. The basic salary will take care of that.

Furthermore, the basic salary has the additional advantage of being something to which I can attach an increased amount to get doctors to go into unattractive areas. It may also – and here our position is not quite so definite – be the means of attaching additional remuneration for special courses and special acquirements. The basic salary, however, must not be too large otherwise it is a disguised form of capitation. Therefore, the main source at the moment through which a general practitioner will obtain his remuneration will be capitation. I have also made – and I quite frankly admit it to the House – a further concession which I know will be repugnant in some quarters. The doctor, the general practitioner and the specialist, will be able to obtain fees, but not from anyone who is on any of their own lists, nor will a doctor be able to obtain fees from persons on the lists of his partner, nor from those he has worked with in group practice, but I think it is impracticable to prevent him having any fees at all. To do so would be to create a black market. There ought to be nothing to prevent anyone having advice from another doctor other than his own. Hon. Members know what happens in this field sometimes. An individual hears that a particular doctor in some place is good at this, that or the other thing, and wants to go along for a consultation and pays a fee for it. If the other doctor is better than his own all he will need to do is to transfer to him and he gets him free. It would be unreasonable to keep the patient paying fees to a doctor whose services can be got free. So the amount of fee payment on the part of the general population will be quite small. Indeed, I confess at once if the amount of fee paying is great, the system will break down, because the whole purpose of this scheme is to provide free treatment with no fee paying at all. The same principle applies to the hospitals. If an individual wishes to consult, there is no reason why he should be stopped. As I have said, the fact that a person can transfer from one doctor to another ought to keep fee paying within reasonable proportions.

The same principle applies to the hospitals. Specialists in hospitals will be allowed to have fee-paying patients. I know this is criticised and I sympathise with some of the reasons for the criticism, but we are driven inevitably to this fact, that unless we permit some fee-paying patients in the public hospitals, there will be a rash of nursing homes all over the country. If people wish to pay for additional amenities, or something to which they attach value, like privacy in a single ward, we ought to aim at providing such facilities for everyone who wants them. But while we have inadequate hospital facilities, and while rebuilding is postponed it inevitably happens that some people will want to buy something more than the general health service is providing. If we do not permit fees in hospitals, we will lose many specialists from the public hospitals for they will go to nursing homes. I believe that nursing homes ought to be discouraged. They cannot provide general hospital facilities, and we want to keep our specialists attached to our hospitals and not send them into nursing homes. Behind this there is a principle of some importance. If the State owned a theatre it would not charge the same prices for the different seats. It is not entirely analogous, but it is an illustration. For example, in the dental service the same principle will prevail. The State will provide a certain standard of dentistry free, but if a person wants to have his teeth filled with gold, the State will not provide that.

The third instrument to which the health services are to be articulated is the health centre, to which we attach very great importance indeed. It has been described in some places as an experimental idea, but we want it to be more than that, because to the extent that general practitioners can operate through health centres in their own practice, to that extent will be raised the general standard of the medical profession as a whole. Furthermore, the general practitioner cannot afford the apparatus necessary for a proper diagnosis in his own surgery. This will be available at the health centre. The health centre may well be the maternity and child welfare clinic of the local authority also. The provision of the health centre is, therefore, imposed as a duty on the local authority. There has been criticism that this creates a trichotomy in the services. It is not a trichotomy at all. If you have complete unification it would bring you back to paper planning. You cannot get all services through the regional authority, because there are many immediate and personal services which the local authority can carry out better than anybody else. So, it is proposed to leave those personal services to the local authority, and some will be carried out at the health centre. The centres will vary; there will be larger centres at which there will be dental clinics, maternity and child welfare services, and general practitioners’ consultative facilities, and there will also be smaller centres – surgeries where practitioners can see their patients.

The health centres will be managed entirely by the health authorities. The health centre itself will be provided by the local health authority and facilities will be made available there to the general practitioner. The small ones are necessary, because some centres may be a considerable distance from people’s homes. So it will be necessary to have simpler ones, nearer their homes, fixed in a constellation with the larger ones.

The representatives on the local executives will be able to coordinate what is happening at the health centres. As I say, we regard these health centres as extremely valuable, and their creation will be encouraged in every possible way. Doctors will be encouraged to practise there, where they will have great facilities. It will, of course, be some time before these centres can be established everywhere, because of the absence of these facilities.

There you have the three main instruments through which it is proposed that the health services of the future should be articulated. There has been some criticism. Some have said that the preventive services should be under the same authority as the curative services. I wonder whether Members who advance that criticism really envisage the situation which will arise. What are the preventive services – Housing, water, sewerage, river pollution prevention, food inspection – are all these to be under a regional board? If so, a regional board of that sort would want the Albert Hall in which to meet. This, again, is paper planning. It is unification for unification’s sake. There must be a frontier at which the local joins the national health service. You can fix it here or there, but it must be fixed somewhere. It is said that there is some contradiction in the health scheme because some services are left to the local authority and the rest to the national scheme. Well, day is joined to night by twilight, but nobody has suggested that it is a contradiction in nature. The argument that this is a contradiction in health services is purely pedantic, and has no relation to the facts.

It is also suggested that because maternity and child welfare services come under the local authority, and gynaecological services come under the regional board, that will make for confusion. Why should it? Continuity between one and the other is maintained by the user. The hospital is there to be used. If there are difficulties in connection with birth, the gynaecologist at the hospital centre can look after them. All that happens is that the midwife will be in charge the mother will be examined properly, as she ought to be examined then, if difficulties are anticipated, she can have her child in hospital, where she can be properly looked after by the gynaecologist. When she recovers, and is a perfectly normal person, she can go to the maternity and child welfare centre for post-natal treatment. There is no confusion there. The confusion is in the minds of those who are criticising the proposal on the ground that there is a trichotomy in the services, between the local authority, the regional board and the health centre.

I apologise for detaining the House so long, but there are other matters to which I must make some reference. The two Amendments on the Order Paper rather astonish me. The hon. Member for Denbigh informs me, in his Amendment, that I have not sufficiently consulted the medical profession – I intend to read the Amendment to show how extravagant the hon. Member has been. He says that he and his friends are:

“unable to agree to a measure containing such far reaching proposals involving the entire population without any consultations having taken place between the Minister and the organisations and bodies representing those who will be responsible for carrying out its provisions…”

I have had prepared a list of conferences I have attended. I have met the medical profession, the dental profession, the pharmacists, nurses and midwives, voluntary hospitals, local authorities, eye services, medical aid services, herbalists, insurance committees, and various other organisations. I have had 20 conferences. The consultations have been very wide. In addition, my officials have had 13 conferences, so that altogether there have been 33 conferences with the different branches of the profession about the proposals. Can anybody argue that that is not adequate consultation? Of course, the real criticism is that I have not conducted negotiations. I am astonished that such a charge should lie in the mouth of any Member of the House. If there is one thing that will spell the death of the House of Commons it is for a Minister to negotiate Bills before they are presented to the House. I had no negotiations, because once you negotiate with outside bodies two things happen. They are made aware of the nature of the proposals before the House of Commons itself; and furthermore, the Minister puts himself into an impossible position, because, if he has agreed things with somebody outside he is bound to resist Amendments from Members in the House. Otherwise he does not play fair with them. I protested against this myself when I was a Private Member. I protested bitterly, and I am not prepared, strange though it may seem, to do something as a Minister which as a Private Member I thought was wrong. So there has not been negotiation, and there will not be negotiation, in this matter. The House of Commons is supreme, and the House of Commons must assert its supremacy, and not allow itself to be dictated to by anybody, no matter how powerful and how strong he may be.

These consultations have taken place over a very wide field, and, as a matter of fact, have produced quite a considerable amount of agreement. The opposition to the Bill is not as strong as it was thought it would be. On the contrary, there is very considerable support for this Measure among the doctors themselves. I myself have been rather aggrieved by some of the statements which have been made. They have misrepresented the proposals to a very large extent, but as these proposals become known to the medical profession, they will appreciate them, because nothing should please a good doctor more than to realise that, in future, neither he nor his patient will have any financial anxiety arising out of illness.

The leaders of the Opposition have on the Order Paper an Amendment which expresses indignation at the extent to which we are interfering with charitable foundations. The Amendment states that the Bill “gravely menaces all charitable foundations by diverting to purposes other than those intended by the donors the trust funds of the voluntary hospitals.”

I must say that when I read that Amendment I was amused. I have been looking up some precedents. I would like to say, in passing, that a great many of these endowments and foundations have been diversions from the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The main contributor was the Chancellor of the Exchequer. But I seem to remember that, in 1941, hon. Members opposite were very much vexed by what might happen to the public schools, and they came to the House and asked for the permission of the House to lay sacrilegious hands upon educational endowments centuries old. I remember protesting against it at the time – not, however, on the grounds of sacrilege. These endowments had been left to the public schools, many of them for the maintenance of the buildings, but hon. Members opposite, being concerned lest the war might affect their favourite schools, came to the House and allowed the diversion of money from that purpose to the payment of the salaries of the teachers and the masters. There have been other interferences with endowments. Wales has been one of the criminals. Disestablishment interfered with an enormous number of endowments. Scotland also is involved. Scotland has been behaving in a most sacrilegious manner; a whole lot of endowments have been waived by Scottish Acts. I could read out a large number of them, but I shall not do so.

Do hon. Members opposite suggest that the intelligent planning of the modern world must be prevented by the endowments of the dead? Are we to consider the dead more than the living? Are the patients of our hospitals to be sacrificed to a consideration of that sort?

We are not, in fact, diverting these endowments from charitable purposes. It would have been perfectly proper for the Chancellor of the Exchequer to have taken over these funds, because they were willed for hospital purposes, and he could use them for hospital purposes; but we are doing no such thing. The teaching hospitals will be left with all their liquid endowments and more power. We are not interfering with the teaching hospitals’ endowments. Academic medical education will be more free in the future than it has been in the past. Furthermore, something like £32 million belonging to the voluntary hospitals as a whole is not going to be taken from them. On the contrary, we are going to use it, and a very valuable thing it will be; we are going to use it as a shock absorber between the Treasury, the central Government, and the hospital administration. They will be given it as free money which they can spend over and above the funds provided by the State.

I welcome the opportunity of doing that, because I appreciate, as much as hon. Members in any part of the House, the absolute necessity for having an elastic, resilient service, subject to local influence as well as to central influence; and that can be accomplished by leaving this money in their hands. I shall be prepared to consider, when the Bill comes to be examined in more detail, whether any other relaxations are possible, but certainly, by leaving this money in the hands of the regional board, by allowing the regional board an annual budget and giving them freedom of movement inside that budget, by giving power to the regional board to distribute this money to the local management committees of the hospitals, by various devices of that sort, the hospitals will be responsible to local pressure and subject to local influence as well as to central direction.

I think that on those grounds the proposals can be defended. They cover a very wide field indeed, to a great deal of which I have not been able to make reference; but I should have thought it ought to have been a pride to hon. Members in all parts of the House that Great Britain is able to embark upon an ambitious scheme of this proportion. When it is carried out, it will place this country in the forefront of all countries of the world in medical services. I myself, if I may say a personal word, take very great pride and great pleasure in being able to introduce a Bill of this comprehensiveness and value. I believe it will lift the shadow from millions of homes. It will keep very many people alive who might otherwise be dead. It will relieve suffering. It will produce higher standards for the medical profession. It will be a great contribution towards the wellbeing of the common people of Great Britain. For that reason, and for the other reasons I have mentioned, I hope hon. Members will give the Bill a Second Reading.

Edward Heath: 'This debate is preventing us from giving real attention and real resources to the problems of crime', Death penalty vote - 1983

13 July 1983, House of Commons, Westminster, United Kingdom

I wish initially to address myself to the general question of capital punishment. I think that my position is well known to all hon. Members. For more than 20 years I have been opposed to capital punishment for all crimes of homicide, and I have always voted against it. I intend to do so tonight. My position is not only as strong as it ever was; it has been confirmed in recent years.

For nearly 20 years capital punishment has been abolished in this country. My hon. and learned Friend the Member for Fylde (Sir E. Gardner), who moved the resolution with great restraint and wisdom, wishes to change the status quo. He and those who support him must prove that it is necessary, in fact vital, to change the status quo. The onus of proof rests with him and his friends. When the House judges the issue and votes tonight, it should ask itself whether the proposer of the resolution and his supporters have proved beyond any shadow of doubt that it is vital to change the status quo.

In my judgment—and I say this with great respect for my hon. and learned Friend whom I have known for many years—he has not proved 'his case. He said quite frankly that he did not intend to rely on statistics. The Home Secretary rightly said the same. If they did, they would have to explain why the increase in homicides began long before the abolition of the death penalty and why the increase in ordinary crimes of violence has been many times greater than the increase in homicides. It is that factor which has produced attention in the public mind. The growth of lesser crimes of violence has been so great that the public has deduced that the only answer is 899 to deal with homicide by capital punishment. That is a confusion in the public mind. A great deal rests upon us to remove that confusion.

My hon. and learned Friend did not introduce the question of retribution and revenge, although it was mentioned by the right hon. Member for Birmingham, Sparkbrook (Mr. Hattersley). I was saddened to hear murmurs in some parts of the House that appeared to support retribution and revenge. Quite frankly, from any moral viewpoint, I find revenge completely unacceptable. I do not believe that it is for the House to decide whether there should be revenge—[Interruption.] If some of my hon. Friends want revenge, I hope that they will say so and also state their position on other issues that they consider require revenge. It is not for the House or for Parliament to decide retribution either. That lies elsewhere at other times. That is why I cannot accept either of the arguments of revenge or retribution.

My hon. and learned Friend said that our purpose must be to secure the safety of the people of this realm to the greatest possible extent. That is the task of Government both externally and internally, and I agree with him entirely. The question at issue is whether the restoration of capital punishment will improve the security of the people of this realm. That issue remains unproven.

My hon. and learned Friend said that that is a matter of judgment. It is. Others would say that it is a matter of instinct—indeed that has already been said—but in my view the judgment, if it is in favour of restoration, is wrong. This is far too great a matter to rest on instinct. We need more substantial reasons than just instinct for changing the status quo.

I come next to the point which in recent years I have found more and more worrying and more and more impressive. I refer to condemnation by mistake. I find it impossible to accept a penalty that is irreversible when it is so apparent that a number of mistakes have been made. One of my hon. Friends said on the radio that if no one else is prepared to hang people he is quite prepared to do the job himself—[HON. MEMBERS: "Which one?"] I ask him a rather different question. Because of his views, is he prepared to be hanged by mistake? I am not asking my hon. Friend to reply on the spur of the moment. I shall let him give due consideration to the problem before he finally makes up his mind.

I wish now to deal with the specific amendments on the Order Paper about the restoration of capital punishment in particular cases. In this respect, I emphasise what was said by the right hon. Member for Sparkbrook and in great detail by my right hon. and learned Friend the Home Secretary about the Homicide Act 1957. I agree with everything that my right hon. and learned Friend said about that. The Homicide Act 1957 was largely shaped by Viscount Kilmuir as Lord Chancellor. I was involved as the Chief Whip of the Government of the day in trying to bring together those who felt strongly about capital punishment and the abolitionists. The Government wanted to lift the problem out of the constant battle in the House of Commons and try to get public support for a final position. That Act lasted for only eight years. It failed, as the Home Secretary said. It failed because the general public was not prepared to support an Act—nor was the judiciary for that matter—which said that one kind of murderer was worthy of the death penalty and that another 900 kind was not; that if a public figure was shot crossing Trafalgar Square that was a matter for the death penalty, but that if a man poisoned his wife that was a matter between the two of them and did not deserve the death penalty.

There is a basic lesson here about trying to pick out particular aspects of homicide for the death penalty. I believe that the public would quickly say "Yes, if there is to be a death penalty, is not such and such a case also worthy of it?" That is the fundamental argument of principle against trying to select particular aspects of homicide as justifying the death penalty.

If there is to be a selection, I regard the case for the selection of terrorism as the weakest. If murder of the police or prison warders were to be selected, I think that the public would say that those people have a rather better chance of looking after themselves than they, the innocent public. Terrorists present great problems. I think that the Home Secretary is underestimating the determination of terrorists in Northern Ireland and elsewhere, quite regardless of death, to carry through their purposes. Even if one is dealing with Arab terrorists, one finds that very few of them are paid marksmen. If they are paid marksmen, they will weigh up the risks against the penalties. If money is what they want they will take the risk. Therefore, I cannot see that the argument for capital punishment for terrorists is a powerful one.

I come now to the definition of terrorism, the importance of which I hope my right hon. and learned Friend will not underestimate, as he glossed over it this afternoon. If there is to be the final capital penalty for terrorism, there is the problem of judges and juries deciding whether a person is a political terrorist. There has been criticism in the Province of attempts to deal with the IRA on the basis that its members should, when arrested, be treated as political prisoners, and it has been said that that is an immense mistake. Exactly this definition, as has so rightly been pointed out, would have to be made permanently for capital punishment if the amendment were agreed. I do not believe that one can gloss over the issue of defining terrorism or of how a jury and the judge would handle it.

Even more important — as the Home Secretary emphasised—is that there is no hope of returning to jury verdicts in Northern Ireland. One will not persuade a jury to convict if there is the death penalty. My right hon. and learned Friend then referred to a judge and perhaps two assessors. But is the Northern Ireland judiciary in favour of dealing with IRA terrorism by a judge and two assessors? I cannot believe for one moment that the judiciary would accept that. I lived through all the problems of 1970 to 1974 and have been back to Northern Ireland many times since. I know the views of the people there and, leaving aside the impact on the IRA, I cannot believe that our judiciary or the Northern Ireland judiciary would be prepared to deal with these cases with an assessor sitting on each side.

Therefore, as my right hon. Friend the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland has already said, it is out of the question for practical reasons to apply capital punishment there. But we cannot punish terrorist murderers on the mainland by imposing the death penalty if we do not do so in Northern Ireland. The number of cases here is comparatively few—a few Arab and other terrorists—but from the public's point of view, let alone all the other considerations, it is impossible to deal with an Arab 901 terrorist who shoots the Israeli ambassador in one way but to deal with the same crime differently in Northern Ireland, which most people consider to be the home of terrorism. Amendment (e) therefore is entirely impractical.

I am astonished—I must not say that—I was taken unawares by the fact that my right hon. and learned Friend the Home Secretary argued as he did. His argument did not seem to deal with any of the basic problems of making terrorism a separate capital crime. Other European countries have had great problems with terrorism—for example, the Federal Republic of Gennany and the Italian Republic. They have dealt with those problems not by bringing back capital punishment, but in other ways, largely by effective police action and by reducing the status of the terrorists so that they could not gain public support. The same is true of the Netherlands. I do not support the argument that we of all European countries should have to reintroduce capital punishment to deal with terrorism.

I conclude with these points. First, we must consider what changes there have been over the past 20 years. One change has been the immense growth of the media—television, radio and the press — and the almost complete removal of privacy. The media's impact in rousing public feeling on the occasion of an execution would be many times what it was in the days before the abolition of capital punishment. One cannot encourage a deeper feeling for the spirituality of man when he is being influenced all the time by the media dealing with executions in that way. That in itself is a powerful argument against capital punishment.

When one considers what has happened in the few states of the United States that have restored capital punishment, one realises the growth in the influence of the media over the past 20 years. It is seen in the horrifying stories that appear before, during and after an execution, especially when men plead for death, which shows that death is not for them a deterrent. I believe that the impact on people is terrible.

Secondly, I am sure, having listened to these debates for 30 years, that the constant emphasis on capital punishment is preventing us from giving real attention and real resources to the problems of crime in a modern democracy. The Government have done a great deal. At one stage criminals had much greater resources than the police. They had better radio facilities, modern communications, such as the use of motorways and other technical devices as well as more up-to-date firearms. The police have now caught up a great deal. We must recognise that if we really are to tackle the per al problems of the country we must turn our attention to that, instead of automatically saying that the answer is hanging and flogging.

I hope, therefore, that this debate can settle it for this Parliament and for many years to come. If my hon. and learned Friend the Member for Fylde is right about that — he said that it might be the last time Parliament would vote on the issue—then I warmly support the fact of him having put the motion forward—though I want to see it defeated—I hope for the last time.

I can claim to speak with a certain amount of experience. When one first comes into the House, one faces many pressures in relation to the way in which one should vote. This has therefore become an early test for many of the victors in the recent general election. My 902 career in the House, covering 33 years, has not been entirely without controversy. I think back to debates on Suez, the abolition of resale price maintenance, the European negotiations, the war in the Middle East, the whole reform of the trade union movement and, for more than 20 years, the abolition of capital punishment.

I can say with honesty to every person who has had the privilege of entering the House that, having said clearly where I stood, and having explained to my constituents why I took up the position that I did, they have accepted that as being the right of their Member of Parliament. I hope that that will always be the case. It is the basis of the British constitution; we are not mandated, we cannot be mandated, by a selection committee, by a constituency committee or by the public as whole.

This is the occasion, above all, when we must use our own judgment. I hope that tonight every hon. Member, and particularly new hon. Members, will feel free to use their judgment. I do not believe that the case for the reintroduction of the death penalty has been proved and I therefore urge the House to reject the motion and all the amendments.

Duff Cooper: 'A moment may come when, owing to the invasion of Czechoslovakia, a European war will begin', Speech opposing Appeasement - 1938

3 October 1938, Westminster, United Kingdom

The House will, I am sure, appreciate the peculiarly difficult circumstances in which I am speaking this afternoon. It is always a painful and delicate task for a Minister who has resigned to explain his reasons to the House of Commons, and my difficulties are increased this afternoon by the fact, of which I am well aware, that the majority of the House are most anxious to hear the Prime Minister and that I am standing between them and him. But I shall have, I am afraid, to ask for the patience of the House, because I have taken a very important, for me, and difficult decision, and I feel that I shall have to demand a certain amount of time in which to make plain to the House the reasons for which I have taken it.

At the last Cabinet meeting that I attended, last Friday evening, before I succeeded in finding my way to No. 10, Downing Street, I was caught up in the large crowd that were demonstrating their enthusiasm and were cheering, laughing, and singing; and there is no greater feeling of loneliness than to be in a crowd of happy, cheerful people and to feel that there is no occasion for oneself for gaiety or for cheering. That there was every cause for relief I was deeply aware, as much as anybody in this country, but that there was great cause for self-congratulation I was uncertain. Later, when I stood in the hall at Downing Street, again among enthusiastic throngs of friends and colleagues who were all as cheerful, happy, glad, and enthusiastic as the crowd in the street, and when I heard the Prime Minister from the window above saying that he had returned, like Lord Beaconsfield, with "peace with honour," claiming that it was peace for our time, once again I felt lonely and isolated; and when later, in the Cabinet room, all his other colleagues were able to present him with 30 bouquets, it was an extremely painful and bitter moment for me that all that I could offer him was my resignation.

Before taking such a step as I have taken, on a question of international policy, a Minister must ask himself many questions, not the least important of which is this: Can my resignation at the present time do any material harm to His Majesty's Government; can it weaken our position; can it suggest to our critics that there is not a united front in Great Britain? Now I would not have flattered myself that my resignation was of great importance, and I did feel confident that so small a blow could easily be borne at the present time, when I think that the Prime Minister is more popular than he has ever been at any period; but had I had any doubts with regard to that facet of the problem, they would have been set at rest, I must say, by the way in which my resignation was accepted, not, I think, with reluctance, but really with relief.

I have always been a student of foreign politics. I have served 10 years in the Foreign Office, and I have studied the history of this and of other countries, and I have always believed that one of the most important principles in foreign policy and the conduct of foreign policy should be to make your policy plain to other countries, to let them know where you stand and what in certain circumstances you are prepared to do. I remember so well in 1914 meeting a friend, just after the declaration of war, who had come back from the British Embassy in Berlin, and asking him whether it was the case, as I had seen it reported in the papers, that the Berlin crowd had behaved very badly and had smashed all the windows of the Embassy, and that the military had had to be called out in order to protect them. I remember my friend telling me that, in his opinion and in that of the majority of the staff, the Berlin crowd were not to blame, that the members of the British Embassy staff had great sympathy with the feelings of the populace, because, they said, "These people have never thought that there was a chance of our coming into the war." They were assured by their Government—and the Government themselves perhaps believed it—that Britain would remain neutral, and therefore it came to, them as a shock when, having already, 31 been engaged with other enemies, as they were, they found that Great Britain had turned against them.

I thought then, and I have always felt, that in any other international crisis that should occur our first duty was to make it plain exactly where we stood and what we would do. I believe that the great defect in our foreign policy during recent months and recent weeks has been that we have failed to do so. During the last four weeks we have been drifting, day by day, nearer into war with Germany, and we have never said, until the last moment, and then in most uncertain terms, that we were prepared to fight. We knew that information to the opposite effect was being poured into the ears of the head of the German State. He had been assured, reassured, and fortified in the opinion that in no case would Great Britain fight.

When Ministers met at the end of August on their return from a holiday there was an enormous accumulation of information from all parts of the world, the ordinary information from our diplomatic representatives, also secret, and less reliable information from other sources, information from Members of Parliament who had been travelling on the Continent and who had felt it their duty to write to their friends in the Cabinet and give them first-hand information which they had received from good sources. I myself had been travelling in Scandinavia and in the Baltic States, and with regard to all this information—Europe was very full of rumours at that time—it was quite extraordinary the unanimity with which it pointed to one conclusion and with which all sources suggested that there was one remedy. All information pointed to the fact that Germany was preparing for war at the end of September, and all recommendations agreed that the one way in which it could be prevented was by Great Britain making a firm stand and stating that she would be in that war, and would be upon the other side.

I had urged even earlier, after the rape of Austria, that Great Britain should make a firm declaration of what her foreign policy was, and then and later I was met with this, that the people of this country are not prepared to fight for Czechoslovakia. That is perfectly true, 32 but I tried to represent another aspect of the situation, that it was not for Czechoslovakia that we should have to fight, that it was not for Czechoslovakia that we should have been fighting if we had gone to war last week. God knows how thankful we all are to have avoided it, but we also know that the people of this country were prepared for it—resolute, prepared, and grimly determined. It was not for Serbia that we fought in 1914. It was not even for Belgium, although it occasionally suited some people to say so. We were fighting then, as we should have been fighting last week, in order that one great Power should not be allowed, in disregard of treaty obligations, of the laws of nations and the decrees of morality to dominate by brutal force the Continent of Europe. For that principle we fought against Napoleon Buonaparte, and against Louis XIV of France and Philip II of Spain. For that principle we must ever be prepared to fight, for on the day when we are not prepared to fight for it we forfeit our Empire, our liberties and our independence.

I besought my colleagues not to see this problem always in terms of Czechoslovakia, not to review it always from the difficult strategic position of that small country, but rather to say to themselves, "A moment may come when, owing to the invasion of Czechoslovakia, a European war will begin, and when that moment comes we must take part in that war, we cannot keep out of it, and there is no doubt upon which side we shall fight. Let the world know that and it will give those who are prepared to disturb the peace reason to hold their hand." It is perfectly true that after the assault on Austria the Prime Minister made a speech in this House—an excellent speech with every word of which I was in complete agreement—and what he said then was repeated and supported by the Chancellor of the Exchequer at Lanark. It was, however, a guarded statement. It was a statement to the effect that if there were such a war it would be unwise for anybody to count upon the possibility of our staying out.

That is not the language which the dictators understand. Together with new methods and a new morality they have introduced also a new vocabulary into Europe. They have discarded the old 33 diplomatic methods of correspondence. Is it not significant that during the whole of this crisis there has not been a German Ambassador in London and, so far as I am aware, the German ChargÉ d'Affaires has hardly visited the Foreign Office? They talk a new language, the language of the headlines of the tabloid Press, and such guarded diplomatic and reserved utterances as were made by the Prime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequer mean nothing to the mentality of Herr Hitler or Signor Mussolini. I had hoped that it might be possible to make a statement to Herr Hitler before he made his speech at Nuremberg. On all sides we were being urged to do so by people in this country, by Members in this House, by Leaders of the Opposition, by the Press, by the heads of foreign States, even by Germans who were supporters of the regime and did not wish to see it plunged into a war which might destroy it. But we were always told that on no account must we irritate Herr Hitler; it was particularly dangerous to irritate him before he made a public speech, because if he were so irritated he might say some terrible things from which afterwards there would be no retreat. It seems to me that Herr Hitler never makes a speech save under the influence of considerable irritation, and the addition of one more irritant would not, I should have thought, have made a great difference, whereas the communication of a solemn fact would have produced a sobering effect.

After the chance of Nuremberg was missed I had hoped that the Prime Minister at his first interview with Herr Hitler at Berchtesgaden would make the position plain, but he did not do so. Again, at Godesberg I had hoped that that statement would be made in unequivocal language. Again I was disappointed. Hitler had another speech to make in Berlin. Again an opportunity occurred of telling him exactly where we stood before he made that speech, but again the opportunity was missed, and it was only after the speech that he was informed. He was informed through the mouth of a distinguished English civil servant that in certain conditions we were prepared to fight. We know what the mentality or something of the mentality of that great dictator is. We know that a message delivered strictly according to instructions with at least three qualifying clauses was not likely to produce upon 34 him on the morning after his great oration the effect that was desired. Honestly, I did not believe that he thought there was anything of importance in that message. It certainly produced no effect whatever upon him and we can hardly blame him.

Then came the last appeal from the Prime Minister on Wednesday morning. For the first time from the beginning to the end of the four weeks of negotiations Herr Hitler was prepared to yield an inch, an ell perhaps, but to yield some measure to the representations of Great Britain. But I would remind the House that the message from the Prime Minister was not the first news that he had received that morning. At dawn he had learned of the mobilisation of the British Fleet. It is impossible to know what are the motives of man and we shall probably never be satisfied as to which of these two sources of inspiration moved him most when he agreed to go to Munich, but wo do know that never before had he given in and that then he did. I had been urging the mobilisation of the Fleet for many days. I had thought that this was the kind of language which would be easier for Herr Hitler to understand than the guarded language of diplomacy or the conditional clauses of the Civil Service. I had urged that something in that direction might be done at the end of August and before the Prime Minister went to Berchtesgaden. I had suggested that it should accompany the mission of Sir Horace Wilson. I remember the Prime Minister stating it was the one thing that would ruin that mission, and I said it was the one thing that would lead it to success.

That is the deep difference between the Prime Minister and myself throughout these days. The Prime Minister has believed in addressing Herr Hitler through the language of sweet reasonableness. I have believed that he was more open to the language of the mailed fist. I am glad so many people think that sweet reasonableness has prevailed, but what actually did it accomplish? The Prime Minister went to Berchtesgaden with many excellent and reasonable proposals and alternatives to put before the Fuhrer, prepared to argue and negotiate, as anybody would have gone to such a meeting. He was met by an ultimatum. So far as I am aware no 35 suggestion of an alternative was ever put forward. Once the Prime Minister found himself in the atmosphere of Berchtesgaden and face to face with the personality of Hitler he knew perfectly well, being a good judge of men, that it would be a waste of time to put forward any alternative suggestion. So he returned to us with those proposals, wrapped up in a cloak called "Self-determination," and laid them before the Cabinet. They meant the partition of a country, the cession of territory, they meant what, when it was suggested by a newspaper some weeks or days before, had been indignantly repudiated throughout the country.

After long deliberation the Cabinet decided to accept that ultimatum, and I was one of those who agreed in that decision. I felt all the difficulty of it; but I foresaw also the danger of refusal. I saw that if we were obliged to go to war it would be hard to have it said against us that we were fighting against the principle of self-determination, and I hoped that if a postponement could be reached by this compromise there was a possibility that the final disaster might be permanently avoided. It was not a pleasant task to impose upon the Government of Czechoslovakia so grievous a hurt to their country, no pleasant or easy task for those upon whose support the Government of Czechoslovakia had relied to have to come to her and say "You have got to give up all for which you were prepared to fight"; but, still, she accepted those terms. The Government of Czechoslovakia, filled with deep misgiving, and with great regret, accepted the harsh terms that were proposed to her.

That was all that we had got by sweet reasonableness at Berchtesgaden. Well, I did think that when a country had agreed to be partitioned, when the Government of a country had agreed to split up the ancient Kingdom of Bohemia, which has existed behind its original frontier for more than 1,000 years, that was the ultimate demand that would be made upon it, and that after everything which Herr Hitler had asked for in the first instance had been conceded he would be willing, and we should insist, that the method of transfer of those territories should be conducted in a normal, in a civilised, manner, as such transfers have always been conducted in the past.

36 The Prime Minister made a second visit to Germany, and at Godesberg he was received with flags, bands, trumpets and all the panoply of Nazi parade; but he returned again with nothing but an ultimatum. Sweet reasonableness had won nothing except terms which a cruel and revengeful enemy would have dictated to a beaten foe after a long war. Crueller terms could hardly be devised than those of the Godesberg ultimatum. The moment I saw them I said to myself, "If these are accepted it will be the end of all decency in the conduct of public affairs in the world." We had a long and anxious discussion in the Cabinet with regard to the acceptance or rejection of those terms. It was decided to reject them, and that information, also, was conveyed to the German Government. Then we were face to face with an impossible position, and at the last moment—not quite the last moment, but what seemed the last moment—another effort was made, by the dispatch of an emissary to Herr Hitler with suggestions for a last appeal. That emissary's effort was in vain, and it was only, as the House knows, on that fateful Wednesday morning that the final change of policy was adopted. I believe that change of policy, as I have said, was due not to any argument that had been addressed to Herr Hitler—it has never been suggested that it was—but due to the fact that for the first moment he realised, when the Fleet was mobilised, that what his advisers had been assuring him of for weeks and months was untrue and that the British people were prepared to fight in a great cause.