11 November 2018, Paris, France

On November 7, 1918, when Bugle Corporal Pierre Sellier sounded the first ceasefire at around 10 a.m., many soldiers couldn’t believe it; they then emerged slowly from their positions while, in the distance, the same bugle calls repeated the ceasefire and then the notes of the Last Post, before church bells spread the news throughout the country.

On November 11, 1918, at 11 a.m., 100 years ago to the day and the hour, in Paris and throughout France, the bugles sounded and the bells of every church rang out.

It was the Armistice.

It was the end of four long and terrible years of deadly fighting. And yet the Armistice didn’t mean peace. And in the east, for several years, appalling wars continued.

Here, that same day, the French and their allies celebrated their victory. They had fought for their homelands and for freedom. To that end, they had agreed to every sacrifice and every kind of suffering. They had experienced a hell that no one can imagine.

We should take a moment to remember that huge procession of soldiers from metropolitan France and the empire, legionnaires and Garibaldians, and foreigners who had come from all over the world because, for them, France represented everything decent in the world.

Alongside the shadows of Peugeot, the first soldier to fall, and Trébuchon, the last to die for France 10 minutes before the Armistice, they include the primary schooteacher Kléber Dupuy who defended Duaumont, Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars in the Marching Regiment of the Foreign Legion, soldiers from the Basque, Breton and Marseille regiments, Captain de Gaulle, whom nobody knew then, Julien Green the American at the door of his ambulance, Montherlant and Giono, Charles Péguy and Alain Fournier who fell in the first weeks, and Joseph Kessel who had come from Orenburg in Russia.

And all the others, all the others who are ours, or rather to whom we belong and whose names we can read on every monument, from the sunny mountains of Corsica to the Alpine valleys, from Sologne to the Vosges, from the Pointe du Raz to the Spanish border. Yes, a single France, rural and urban, middle-class, aristocratic and working-class, of all hues, where priests and anti-clericals suffered side by side and whose heroism and pain made us what we are.

During those four years, Europe very nearly committed suicide. Mankind was plunged into a hideous maze of ruthless battles, a hell that swallowed up every soldier, whatever side they were on and whatever their nationality.

From the next day, the day after the Armistice, the grim count began of the dead, the wounded, the maimed and the missing. Here in France, but also in each country, families waited in vain for months, for the return of a father, a brother, a husband, a fiancé, and those missing people also included the admirable women who worked alongside the soldiers.

Ten million dead.

Six million wounded and maimed.

Three million widows.

Six million orphans.

Millions of civilian victims.

A million shells fired on French soil alone.

The world discovered the scale of the wounds concealed by the fervor of fighting. The tears of the dying were replaced by those of the survivors, because the whole world had come to fight on French soil. Young men from every province and from overseas France, young men from Africa, the Pacific, the Americas and Asia came to die far from their families, in villages whose names they didn’t even know.

The millions of witnesses from every nation recounted the horror of the fighting, the stench of the trenches, the desolation of the battlefields, the cries of the wounded in the night, and the destruction of lush landscapes until all that remained were the charred silhouettes of trees. Many of those who returned had lost their youth, their ideals, the joy of living. Many were disfigured, blind, amputated. For a long time, winners and losers mourned equally.

1918 was 100 years ago. It seems far away. And yet it was only yesterday!

I’ve traveled the length and breadth of French lands where the harshest battles took place. In my country I’ve seen the still grey and sterile earth of the battlefields! I’ve seen the destroyed villages which had no more inhabitants to rebuild them and which now only bear witness, stone by stone, to the folly of man!

I’ve seen on our monuments the litany of Frenchmen’s names alongside the names of foreigners who died under the French sun; I’ve seen where the bodies of our soldiers lie buried beneath a landscape that has become innocent again, just as I’ve seen where, jumbled together in mass graves, lie the bones of German and French soldiers who, one freezing winter, killed one another for a few meters of ground…

The traces of that war have never been erased in the lands of France, in those of Europe and the Middle East, or in the memories of people throughout the world.

Let’s remember! Let’s not forget! Because the memory of those sacrifices encourages us to be worthy of those who died for us, so that we could live in freedom!

Let’s remember: let’s take away none of the purity, the idealism, the higher principles that existed in the patriotism of our elders. In those dark hours, that vision of France as a generous nation, of France as a project, of France promoting universal values, was the exact opposite of the egotism of a people who look after only their interests, because patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism: nationalism is a betrayal of it. In saying “our interests first and who cares about the rest!” you wipe out what’s most valuable about a nation, what brings it alive, what leads it to greatness and what is most important: its moral values.

Let us – the other French people – remember what Clemenceau proclaimed on the day of victory, 100 years ago to the day, from the National Assembly rostrum, before the Marseillaise rang out in an unparalleled chorus: France, which fought for what is right and for freedom, would always and forever be a soldier of ideals.

It’s those values and those virtues that sustained the people we’re honoring today, those who sacrificed themselves in the fighting to which the nation and democracy had committed them. It’s those values, those virtues that made them strong, because they guided their hearts.

The lesson of the Great War cannot be that of resentment by one people against others, any more than it can be to forget the past. It’s a rootedness that forces us to think about the future and what is essential.

From 1918 onwards, our predecessors tried to build peace, invented the first forms of international cooperation, dismantled empires, recognized many nations and redrafted borders; they even dreamed then of a political Europe.

But humiliation, the spirit of revenge and the economic and moral crisis fueled the rise of nationalism and totalitarianism. Twenty years later, war came once again to devastate the paths of peace.

Here today, peoples of the whole world, see just how many of your leaders are gathered on this sacred slab, the burial place of our Unknown Soldier, the poilu [First World War infantryman] who is the anonymous symbol of all those who die for their homeland!

Each of those peoples carries in its wake a long cohort of fighters and martyrs who emerged from it. Each of them is the face of that hope for which a whole young generation agreed to die: that of a world finally peaceful again, a world where friendship between peoples prevails over warlike passions, a world where the spirit of reconciliation prevails over the temptation of cynicism, where bodies and forums enable yesterday’s enemies to engage in dialogue and make it the binding force for understanding, the guarantee of a harmony that is finally possible.

On our continent, such is the friendship forged between Germany and France and the desire to build a foundation of shared ambitions. Such is the European Union, a freely agreed union never seen in history, delivering us from our civil wars. Such is the United Nations Organization, the guarantor of a spirit of cooperation to defend common goods in a world whose destiny is inextricably linked and which has learned the lessons of the painful failures of both the League of Nations and the Treaty of Versailles.

It’s this certainty that the worst is never inevitable when men and women of goodwill exist. Let’s tirelessly, unashamedly, fearlessly be those men and women of goodwill!

I know, the old demons are reappearing, ready to do their work of spreading chaos and death. New ideologies are manipulating religions and advocating a contagious obscurantism. At times, history threatens to resume its tragic course and jeopardize the peace we’ve inherited and which we thought we had secured for good with the blood of our ancestors.

So let this anniversary day be one on which there is a renewed sense of eternal loyalty to our dead! Let’s again take the United Nations’ oath to place peace higher than anything, because we know its price, we know its weight, we know its demands!

We political leaders must all, here, on this November 11, 2018, reaffirm to our peoples the genuine, huge responsibility we have of passing on to our children the world previous generations dreamed about.

Let’s combine our hopes instead of pitting our fears against each other! Together, we can keep at bay these threats – global warming, poverty, hunger, disease, inequality and ignorance. We’ve begun this battle and can win it: let’s continue with it, because victory is possible!

Together we can break with the new “treason of the intellectuals” which is at work and fuels untruths, accepts the injustice consuming our peoples and sustains extremes and present-day obscurantism.

Together we can bring about the extraordinary flourishing of science, the arts, trade, education and medicine, which I can see the beginnings of throughout the world, because our world is – if we want it to be – at the dawn of a new era, a civilization taking man’s ambitions and faculties to the highest level.

Ruining this hope because of a fascination with self-absorption, violence and domination would be a mistake which future generations would rightly make us historically responsible for. Here, today, let us face with dignity how we are judged in the future.

France knows what it owes its soldiers and every soldier from all over the world. It respects their greatness.

France respectfully and solemnly pays tribute to the dead of other nations it once fought. It stands at their side.

“It is in vain that our feet detach themselves from the soil that holds the dead”, wrote Guillaume Apollinaire.

On the graves where they are buried, may the certainty flourish that a better world is possible if we want it, decide it, build it and will it with all our heart.

Today, on November 11, 2018, 100 years after a massacre whose scar is still visible on the face of the world, I thank you for this gathering which renews the fraternity of November 11, 1918.

May this gathering not last just one day. This fraternity, my friends, actually calls on us to wage the only battle worth waging: the battle for peace, the battle for a better world.

Long live peace between peoples and states!

Long live the free nations of the world!

Long live the friendship between peoples!

Long live France!

John F Kennedy: ' We shall achieve that peace only with patience and perseverance and courage', Remarks at Veterans Day Ceremony - 1961

11 November 1961, Arlington cemetery, Washington DC, USA

General Gavan, Mr. Gleason, members of the military forces, veterans, fellow Americans:

Today we are here to celebrate and to honor and to commemorate the dead and the living, the young men who in every war since this country began have given testimony to their loyalty to their country and their own great courage.

I do not believe that any nation in the history of the world has buried its soldiers farther from its native soil than we Americans--or buried them closer to the towns in which they grew up.

We celebrate this Veterans Day for a very few minutes, a few seconds of silence and then this country's life goes on. But I think it most appropriate that we recall on this occasion, and on every other moment when we are faced with great responsibilities, the contribution and the sacrifice which so many men and their families have made in order to permit this country to now occupy its present position of responsibility and freedom, and in order to permit us to gather here together.

Bruce Catton, after totaling the casualties which took place in the battle of Antietam, not so very far from this cemetery, when he looked at statistics which showed that in the short space of a few minutes whole regiments lost 50 to 75 percent of their numbers, then wrote that life perhaps isn't the most precious gift of all, that men died for the possession of a few feet of a corn field or a rocky hill, or for almost nothing at all. But in a very larger sense, they died that this country might be permitted to go on, and that it might permit to be fulfilled the great hopes of its founders.

In a world tormented by tension and the possibilities of conflict, we meet in a quiet commemoration of an historic day of peace. In an age that threatens the survival of freedom, we join together to honor those who made our freedom possible. The resolution of the Congress which first proclaimed Armistice Day, described November 11, 1918, as the end of "the most destructive, sanguinary and far-reaching war in the history of human annals." That resolution expressed the hope that the First World War would be, in truth, the war to end all wars. It suggested that those men who had died had therefore not given their lives in vain.

It is a tragic fact that these hopes have not been fulfilled, that wars still more destructive and still more sanguinary followed, that man's capacity to devise new ways of killing his fellow men have far outstripped his capacity to live in peace with his fellow men.

Some might say, therefore, that this day has lost its meaning, that the shadow of the new and deadly weapons have robbed this day of its great value, that whatever name we now give this day, whatever flags we fly or prayers we utter, it is too late to honor those who died before, and too soon to promise the living an end to organized death.

But let us not forget that November 11, 1918, signified a beginning, as well as an end. "The purpose of all war," said Augustine, "is peace." The First World War produced man's first great effort in recent times to solve by international cooperation the problems of war. That experiment continues in our present day--still imperfect, still short of its responsibilities, but it does offer a hope that some day nations can live in harmony.

For our part, we shall achieve that peace only with patience and perseverance and courage--the patience and perseverance necessary to work with allies of diverse interests but common goals, the courage necessary over a long period of time to overcome an adversary skilled in the arts of harassment and obstruction.

There is no way to maintain the frontiers of freedom without cost and commitment and risk. There is no swift and easy path to peace in our generation. No man who witnessed the tragedies of the last war, no man who can imagine the unimaginable possibilities of the next war, can advocate war out of irritability or frustration or impatience.

But let no nation confuse our perseverance and patience with fear of war or unwillingness to meet our responsibilities. We cannot save ourselves by abandoning those who are associated with us, or rejecting our responsibilities.

In the end, the only way to maintain the peace is to be prepared in the final extreme to fight for our country--and to mean it.

As a nation, we have little capacity for deception. We can convince friend and foe alike that we are in earnest about the defense of freedom only if we are in earnest-and I can assure the world that we are.

This cemetery was first established 97 years ago. In this hill were first buried men who died in an earlier war, a savage war here in our own country. Ninety-seven years ago today, the men in Gray were retiring from Antietam, where thousands of their comrades had fallen between dawn and dusk in one terrible day. And the men in Blue were moving towards Fredericksburg, where thousands would soon lie by a stone wall in heroic and sometimes miserable death.

It was a crucial moment in our Nation's history, but these memories, sad and proud, these quiet grounds, this Cemetery and others like it all around the world, remind us with pride of our obligation and our opportunity.

On this Veterans Day of 1961, on this day of remembrance, let us pray in the name of those who have fought in this country's wars, and most especially who have fought in the First World War and in the Second World War, that there will be no veterans of any further war--not because all shall have perished but because all shall have learned to live together in peace.

And to the dead here in this cemetery we say:

They are the race--

they are the race immortal,

Whose beams make broad

the common light of day!

Though Time may dim,

though Death has barred their portal,

These we salute,

which nameless passed away.

Woodrow Wilson: 'Peace without Victory', address to Senate - 1917

22 January 1917, Washington DC, USA

Gentlemen of the Senate,

On the 18th of December last, I addressed an identic note to the governments of the nations now at war requesting them to state, more definitely than they had yet been stated by either group of belligerents, the terms upon which they would deem it possible to make peace. I spoke on behalf of humanity and of the rights of all neutral nations like our own, many of whose most vital interests the war puts in constant jeopardy.

The Central Powers united in a reply which stated merely that they were ready to meet their antagonists in conference to discuss terms of peace. The Entente Powers have replied much more definitely and have stated, in general terms, indeed, but with sufficient definiteness to imply details, the arrangements, guarantees, and acts of reparation which they deem to be indispensable conditions of a satisfactory settlement. We are that much nearer a definite discussion of the peace which shall end the present war. We are that much nearer the discussion of the international concert which must thereafter hold the world at peace.

In every discussion of the peace that must end this war, it is taken for granted that that peace must be followed by some definite concert of power which will make it virtually impossible that any such catastrophe should ever overwhelm us again. Every lover of mankind, every sane and thoughtful man must take that for granted.

I have sought this opportunity to address you because I thought that I owed it to you, as the council associated with me in the final determination of our international obligations, to disclose to you without reserve the thought and purpose that have been taking form in my mind in regard to the duty of our government in the days to come, when it will be necessary to lay afresh and upon a new plan the foundations of peace among the nations.

It is inconceivable that the people of the United States should play no part in that great enterprise. To take part in such a service will be the opportunity for which they have sought to prepare themselves by the very principles and purposes of their polity and the approved practices of their government ever since the days when they set up a new nation in the high and honorable hope that it might, in all that it was and did, show mankind the way to liberty.

They cannot in honor withhold the service to which they are now about to be challenged. They do not wish to withhold it. But they owe it to themselves and to the other nations of the world to state the conditions under which they will feel free to render it.

That service is nothing less than this, to add their authority and their power to the authority and force of other nations to guarantee peace and justice throughout the world. Such a settlement cannot now be long postponed. It is right that before it comes, this government should frankly formulate the conditions upon which it would feel justified in asking our people to approve its formal and solemn adherence to a League for Peace. I am here to attempt to state those conditions.

The present war must first be ended; but we owe it to candor and to a just regard for the opinion of mankind to say that, so far as our participation in guarantees of future peace is concerned, it makes a great deal of difference in what way and upon what terms it is ended. The treaties and agreements which bring it to an end must embody terms which will create a peace that is worth guaranteeing and preserving, a peace that will win the approval of mankind, not merely a peace that will serve the several interests and immediate aims of the nations engaged . We shall have no voice in determining what those terms shall be, but we shall, I feel sure, have a voice in determining whether they shall be made lasting or not by the guarantees of a universal covenant; and our judgment upon what is fundamental and essential as a condition precedent to permanency should be spoken now, not afterwards when it may be too late.

No covenant of cooperative peace that does not include the peoples of the New World can suffice to keep the future safe against war; and yet there is only one sort of peace that the peoples of America could join in guaranteeing. The elements of that peace must be elements that engage the confidence and satisfy the principles of the American governments, elements consistent with their political faith and with the practical convictions which the peoples of America have once for all embraced and undertaken to defend.

I do not mean to say that any American government would throw any obstacle in the way of any terms of peace the governments now at war might agree upon or seek to upset them when made, whatever they might be. I only take it for granted that mere terms of peace between the belligerents will not satisfy even the belligerents themselves. Mere agreements may not make peace secure. It will be absolutely necessary that a force be created as a guarantor of the permanency of the settlement so much greater than the force of any nation now engaged, or any alliance hitherto formed or projected, that no nation, no probable combination of nations, could face or withstand it. If the peace presently to be made is to endure, it must be a peace made secure by the organized major force of mankind.

The terms of the immediate peace agreed upon will determine whether it is a peace for which such a guarantee can be secured. The question upon which the whole future peace and policy of the world depends is this: Is the present war a struggle for a just and secure peace, or only for a new balance of power? If it be only a struggle for a new balance of power, who will guarantee, who can guarantee the stable equilibrium of the new arrangement? Only a tranquil Europe can be a stable Europe. There must be, not a balance of power but a community power; not organized rivalries but a organized, common peace.

Fortunately we have received very explicit assurances on this point. The statesmen of both of the groups of nations now arrayed against one another have said, in terms that could not be misinterpreted, that it was no part of the purpose they had in mind to crush their antagonists. But the implications of these assurances may not be equally to all--may not be the same on both sides of the water. I think it will be serviceable if I attempt to set forth what we understand them to be.

They imply, first of all, that it must be a peace without victory. It is not pleasant to say this. I beg that I may be permitted to put my own interpretation upon it and that it may be understood that no other interpretation was in my thought. I am seeking only to face realities and to face them without soft concealments. Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser, a victor's terms imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently but only as upon quicksand. Only a peace between equals can last. Only a peace the very principle of which is equality and a common participation in a common benefit. The right state of mind, the right feeling between nations, is as necessary for a lasting peace as is the just settlement of vexed questions of territory or of racial and national allegiance.

The equality of nations upon which peace must be founded if it is to last must be an equality of rights; the guarantees exchanged must neither recognize nor imply a difference between big nations and small, between those that are powerful and those that are weak. Right must be based upon the common strength, not upon the individual strength, of the nations upon whose concert peace will depend. Equality of territory or of resources there of course cannot be; nor any other sort of equality not gained in the ordinary peaceful and legitimate development of the peoples themselves. But no one asks or expects anything more than an equality of rights. Mankind is looking now for freedom of life, not for equipoises of power.

And there is a deeper thing involved than even equality of right among organized nations. No peace can last, or ought to last, which does not recognize and accept the principle that governments derive all their just powers from the consent of the governed, and that no right anywhere exists to hand peoples about from sovereignty to sovereignty as if they were property. I take it for granted, for instance, if I may venture upon a single example, that statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, and autonomous Poland, and that, henceforth, inviolable security of life, of worship, and of industrial and social development should be guaranteed to all peoples who have lived hitherto under the power of governments devoted to a faith and purpose hostile to their own.

I speak of this, not because of any desire to exalt an abstract political principle which has always been held very dear by those who have sought to build up liberty in America but for the same reason that I have spoken of the other conditions of peace which seem to me clearly indispensable because I wish frankly to uncover realities. Any peace which does not recognize and accept this principle will inevitably be upset. It will not rest upon the affections or the convictions of mankind. The ferment of spirit of whole populations will fight subtly and constantly against it, and all the world will sympathize. The world can be at peace only if its life is stable, and there can be no stability where the will is in rebellion, where there is not tranquillity of spirit and a sense of justice, of freedom, and of right.

So far as practicable, moreover, every great people now struggling toward a full development of its resources and of its powers should be assured a direct outlet to the great highways of the sea. Where this cannot be done by the cession of territory, it can no doubt be done by the neutralization of direct rights of way under the general guarantee which will assure the peace itself. With a right comity of arrangement, no nation need be shut away from free access to the open paths of the world's commerce.

And the paths of the sea must alike in law and in fact be free. The freedom of the seas is the sine qua non of peace, equality, and cooperation. No doubt a somewhat radical reconsideration of many of the rules of international practice hitherto thought to be established may be necessary in order to make the seas indeed free and common in practically all circumstances for the use of mankind, but the motive for such changes is convincing and compelling. There can be no trust or intimacy between the peoples of the world without them. The free, constant, unthreatened intercourse of nations is an essential part of the process of peace and of development. It need not be difficult either to define or to secure the freedom of the seas if the governments of the world sincerely desire to come to an agreement concerning it.

It is a problem closely connected with the limitation of naval armaments and the cooperation of the navies of the world in keeping the seas at once free and safe. And the question of limiting naval armaments opens the wider and perhaps more difficult question of the limitation of armies and of all programs of military preparation. Difficult and delicate as these questions are, they must be faced with the utmost candor and decided in a spirit of real accommodation if peace is to come with healing in its wings, and come to stay.

Peace cannot be had without concession and sacrifice. There can be no sense of safety and equality among the nations if great preponderating armaments are henceforth to continue here and there to be built up and maintained. The statesmen of the world must plan for peace, and nations must adjust and accommodate their policy to it as they have planned for war and made ready for pitiless contest and rivalry. The question of armaments, whether on land or sea, is the most immediately and intensely practical question connected with the future fortunes of nations and of mankind.

I have spoken upon these great matters without reserve and with the utmost explicitness because it has seemed to me to be necessary if the world's yearning desire for peace was anywhere to find free voice and utterance. Perhaps I am the only person in high authority among all the peoples of the world who is at liberty to speak and hold nothing back. I am speaking as an individual, and yet I am speaking also, of course, as the responsible head of a great government, and I feel confident that I have said what the people of the United States would wish me to say.

May I not add that I hope and believe that I am in effect speaking for liberals and friends of humanity in every nation and of every program of liberty? I would fain believe that I am speaking for the silent mass of mankind everywhere who have as yet had no place or opportunity to speak their real hearts out concerning the death and ruin they see to have come already upon the persons and the homes they hold most dear.

And in holding out the expectation that the people and government of the United States will join the other civilized nations of the world in guaranteeing the permanence of peace upon such terms as I have named I speak with the greater boldness and confidence because it is clear to every man who can think that there is in this promise no breach in either our traditions or our policy as a nation, but a fulfillment, rather, of all that we have professed or striven for.

I am proposing, as it were, that the nations should with one accord adopt the doctrine of President Monroe as the doctrine of the world: that no nation should seek to extend its polity over any other nation or people, but that every people should be left free to determine its own polity, its own way of development--unhindered, unthreatened, unafraid, the little along with the great and powerful.

I am proposing that all nations henceforth avoid entangling alliances which would draw them into competitions of power, catch them in a net of intrigue and selfish rivalry, and disturb their own affairs with influences intruded from without. There is no entangling alliance in a concert of power. When all unite to act in the same sense and with the same purpose, all act in the common interest and are free to live their own lives under a common protection.

I am proposing government by the consent of the governed; that freedom of the seas which in international conference after conference representatives of the United States have urged with the eloquence of those who are the convinced disciples of liberty; and that moderation of armaments which makes of armies and navies a power for order merely, not an instrument of aggression or of selfish violence.

These are American principles, American policies. We could stand for no others. And they are also the principles and policies of forward-looking men and women everywhere, of every modern nation, of every enlightened community. They are the principles of mankind and must prevail.

President Wilson made this speech to the Senate in January 1917. Just over two months later, the U.S. joined the conflict.

Henry Cabot Lodge: 'American I was born', Opposing League of Nations - 1919

12 August 1919, Washington DC, USA

Mr. President:

The independence of the United States is not only more precious to ourselves but to the world than any single possession. Look at the United States today. We have made mistakes in the past. We have had shortcomings. We shall make mistakes in the futureand fall short of our own best hopes. But none the less is there any country today on the face of the earth which can compare with this in ordered liberty, in peace, and in the largest freedom?

I feel that I can say this without being accused of undue boastfulness, for it is the simple fact, and in making this treaty and taking on these obligations all that we do is in a spirit of unselfishness and in a desire for the good of mankind. But it is well to remember that we are dealing with nations every oneof which has a direct individual interest to serve, and there is grave danger in an unshared idealism.

Contrast the United States with any country on the face of the earth today and ask yourself whether the situation of the United States is not the best to be found. I will go as far as anyone in world service, but the first step to world service is the maintenance of the United States.

I have always loved one flag and I cannot share that devotion [with] a mongrel banner created for a League.

You may call me selfish if you will, conservative or reactionary, or use any other harsh adjective you see fit to apply, but an American I was born, an American I have remained all my life. I can never be anything else but an American, and I must think of the United States first, and when I think of the United States first in an arrangement like this I am thinking of what is best for the world, for if the United States fails, the best hopes of mankind fail with it.

I have never had but one allegiance ‐I cannot divide it now. I have loved but one flag and I cannot share that devotion and give affection to the mongrel banner invented for a league. Internationalism, illustrated by the Bolshevik and by the men to whom all countries are alike provided they can make money out of them, is to me repulsive.

National I must remain, and in that way I like all other Americans can render the amplest service to the world. The United States is the world's best hope, but if you fetter her in the interests and quarrels of other nations, if you tangle her in the intrigues of Europe, you will destroy her power for good and endanger her very existence. Leave her to march freely through the centuries to come as in the years that have gone.

Strong, generous, and confident, she has nobly served mankind. Beware how you trifle with your marvellous inheritance, this great land of ordered liberty, for if we stumble and fall freedom and civilization everywhere will go down in ruin.

We are told that we shall 'break the heart of the world 'if we do not take this league just as it stands. I fear that the hearts of the vast majority of mankind would beat on strongly and steadily and without any quickening if the league were to perish altogether. If it should be effectively and beneficently changed the people who would lie awake in sorrow for a single night could be easily gathered in one not very large room but those who would draw a long breath of relief would reach to millions.

We hear much of visions and I trust we shall continue to have visions and dream dreams of a fairer future for the race. But visions are one thing and visionaries are another, and the mechanical appliances of the rhetorician designed to give a picture of a present which does not exist and of a future which no man can predict are as unreal and short‐lived as the steam or canvas clouds, the angels suspended on wires and the artificial lights of the stage.

They pass with the moment of effect and are shabby and tawdry in the daylight. Let us at least be real. Washington's entire honesty of mind and his fearless look into the face of all facts are qualities which can never go out of fashion and which we should all do well to imitate.

Ideals have been thrust upon us as an argument for the league until the healthy mind which rejects cant revolts from them. Are ideals confined to this deformed experiment upon a noble purpose, tainted, as it is, with bargains and tied to a peace treaty which might have been disposed of long ago to the great benefit of the world if it had not been compelled to carry this rider on its back? 'Post equitem sedet atra cura,' Horace tells us, but no blacker care ever sat behind any rider than we shall find in this covenant of doubtful and disputed interpretation as it now perches upon the treaty of peace.

No doubt many excellent and patriotic people see a coming fulfilment of noble ideals in the words 'league for peace.' We all respect and share these aspirations and desires, but some of us see no hope, but rather defeat, for them in this murky covenant. For we, too, have our ideals, even if we differ from those who have tried to establish a monopoly of idealism.

Our first ideal is our country, and we see her in the future, as in the past, giving service to all her people and to the world. Our ideal of the future is that she should continue to render that service of her own free will. She has great problems of her own to solve, very grim and perilous problems, and a right solution, if we can attain to it, would largely benefit mankind.

We would have our country strong to resist a peril from the West, as she has flung back the German menace from the East. We would not have our politics distracted and embittered by the dissensions of other lands. We would not have our country's vigour exhausted or her moral force abated, by everlasting meddling and muddling in every quarrel, great and small, which afflicts the world.

Our ideal is to make her ever stronger and better and finer, because in that way alone, as we believe, can she be of the greatest service to the world's peace and to the welfare of mankind

David Lloyd George: 'This is the story of two little nations', Great Pinnacle of Sacrifice - 1914

21 September 1914, Queens Hall, London, United Kingdom

This is the story of two little nations. The world owes much to the little nations

The greatest art in the world was the work of little nations; the most enduring literature of the world came from little nations; the greatest literature of England came when she was a nation of the size of Belgium fighting a great Empire. The heroic deeds that thrill humanity through generations were the deeds of little nations fighting for their freedom. Yes and the salvation of mankind came through a little nation.

God has chosen little nations as the vessels by which He carriesHis choicest wines to the lips of humanity, to rejoice their hearts, to exalt their vision, to stimulate and strengthen their faith; and if we had stood by when two little nations were being crushed and broken by the brutal hands of barbarism, our shame would have rung down the everlasting ages.

But Germany insists that this is an attack by a lower civilization upon a higher one. As a matter of fact, the attack was begun by the civilization which calls itself the higher one. I am no apologist for Russia; she has perpetrated deeds of which I have no doubt her best sons are ashamed. What Empire has not? But Germany is the last Empire to point the finger of reproach at Russia.

Russia has made sacrifices for freedom—great sacrifices.

Do you remember the cry of Bulgaria when she was torn by the most insensate tyranny that Europe has ever seen? Who listened to that cry? The only answer of the “higher civilization” was that the liberty of the Bulgarian peasants was not worth the life of a single Pomeranian’soldiers. But the “rude barbarians” of the North sent their sons by the thousand to die for Bulgarian freedom. What about England? Go to Greece, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and France—in all those lands I could point out places where the sons of Britain have died for the freedom of those people. France has made sacrifices for the freedom of other lands than her own. Can you name a single country in the world for the freedom of which modern Prussia has ever sacrificed a single life?

By the test of our faith the highest standard of civilization is the readiness to sacrifice for others.

Have you read the Kaiser’s speeches? They are full of the glitter and bluster of German militarism—“mailed fist” and “shining armor”. Poor old mailed fist! Its knuckles are getting a little bruised. Poor shining armor! The shine is being knocked out of it. There is the same swagger and boastfulness runing through the whole of the speeches. The extract which was given in the British weekly this week is a very remarkable product as an illustration of the spirit we have to fight. It is the Kaiser’s speech to his soldiers on the way to the front:

Remember that the German people are the chosen of God. On me, the German Emperor, the Spirit of God has descended. I am His sword, His weapon and His Vicegerent. Woe to the disobedient, and death to cowards and unbelievers.

Lunacy is always distressing, but sometimes it is dangerous; and when you get it manifested in the head of the State, and it has become the policy of a great Empire, it is about time that it should be ruthlessly put away.

I do not believe he meant all these speeches; it is simply the martial straddle he had acquired. But there were men around him who meant every word of them. This was their religion. Treaties? They tangle the feet of Germany in her advance. Cut them with the sword! Little nations? They hinder the advance of Germany heel. The Russia Slav? He challenges the supremacy of Germany in Europe.

Hurl your legions at him and massacre him! Britain? She is a constant menace to the predominance of Germany in the world.

Wrest the trident out of her hand.

Christianity? Sickly sentimentalism about sacrifice for others! Poor pap for German digestion!

We will have a new diet. We will force it upon the world. It will be made in Germany—the diet of blood and iron. What remains? Treaties have gone. The honor of nations has gone. Libery has gone. What is left? Germany. Germany is left!“

Deutschland über Alles!”

That is what we are fighting —that claim to predominance of a material, hard civilization which, if it once rulers and sways the word, liberty goes, democracy vanishes. And unless Britain and her sons come to the rescue it will be a dark day for humanity.

Have you followed the Prussian Junker ’and his doings? We are not fighting the German people are under the heel of this military caste, and it will be a day of rejoicing for the German peasant, artisan and trader when the military caste is broken. You know its pretensions.

They give themselves the air of demigods. They walk the pavements and civilians and their wives are swept into the gutter; they have no right to stand in the way of a great Prussia soldier. Men, women, nations—they all have to go. He thinks all he has to say is, “We are in a hurry.”

That is the answer he gave to Belgium -“Rapidity of action is Germany’s greatest asset,” which means, “I am in a hurry; clear out of my way”

You know the type of motorist, the terror of the roads, with a sixty-horse-power car, who thinks the roads are made for him, and knock down anybody who impedes the actin of his car by a single mile an hour. The Prussian Junker is the road-hog of Europe. Small nationalities in his way are hurled to the roadside, bleeding and broken. Women and children are crushed under the wheels of his cruel car, and Britain is ordered out of his road. All I can say is this: if the old Britain spirit is alive in British hearts, that bully will be torn from his seat. Were he to win, it, would be the greatest catastrophe that has befallen democracy since the day of the Holy Alliance and its ascendancy.

They think we cannot beat them. It will not be easy. It will be a long job; it will be a terrible war; but in the end we shall march through terror to triumph.

We shall need all our qualities—every quality that Britain and its people possess—prudence in counsel, daring in action, tenacity in purpose, courage in defeat, moderation in victory; in all things faith.

It has pleased them to believe and to preach the belief that we are a decadent and degenerate people. They proclaim to the world through their professors that we are a nonheroic nation skulking behind our mahogany counters, whilst we egg on more gallant races to their destruction. This is a description given of us in Germany- “a timorous, craven nation, trusting to its Fleet”

I think they are beginning to find their mistake out already - and there are half a million young men of Britain who have already registered a vow to their King that they will cross the seas and hurl that insult to Britain courage against its perpetrators on the battlefields of France and Germany. We want half a million more; and we shall get them.

I envy you young people your opportunity. They have put up the age limit for the Army, but I am sorry to say I have marched a good many years even beyond that. It is a great opportunity, and opportunity that only comes once in many centuries to the children of men.

For most generations sacrifice comes in drab and weariness of spirit. It comes to you today, and it comes today to us all, in the form of the glow and trill of a great movement for liberty, that impels millions throughout Europe to the same noble end.

It is a great war for the emancipation of Europe from the thralldom of a military caste which has thrown its shadows upon two generations of men, and is now plunging the world into a welter of bloodshed and death.

Some have already given their lives.

There are some who have given more than their own lives; they have their courage, and may God be their comfort and their strength.

But their reward is at hand; those who have fallen have died consecrated deaths.

They have taken their part in the making of a new Europe—a new world. I can see signs of its coming in the glare of the battle-field.

The people will gain more by this struggle in all lands than they comprehend at the present moment. It is true they will be free of the greatest menace to their freedom. That is not all. There is something infinitely greater and more enduring which is emerging and more exalted than the old. I see among all classes, high and low, shedding them of selfishness, a new recognition that the honor of the country does not depend merely on the maintenance of its glory in the stricken field, but also in protecting its homes from distress. It is bringing a new outlook for all classes. The great flood of luxury and sloth which had submerged the land is receding, and a New Britain is appearing.

We can see for the first time the fundamental things that matter in life and that have been obscured from our vision by the tropical growth of prosperity.

May I tell you in a simple parable what I think this war is doing for us? I know a valley in North Wales, between the mountains and the sea. It is a beautiful valley, sung, comfortable, and sheltered by the mountains from all the bitter blasts.

But it is very enervating, and I remember how the boys were in the habit of mountains in the distance, and to be stimulated and freshened by the breezes which came from the hilltops, and by the great spectacle of their grandeur. We have been living in the sheltered valley for generations. We have been too comfortable and too indulgent—many, perhaps, too selfish—and the tern hand of fate has scourged us to an elevation where we can see the great everlasting thngs that matter for a nation the great peaks we had forgotten, of Honor, Duty, Patriotism, and, clad in glittering white, the great pinnacle of Sacrifice pointing like arugged finger as to Heaven.

We shall descend into the valleys again; but as long as the men and women of this generation last, they will carry in their hearts the image of those great mountain peaks whose foundations are not shaken, though Europe rock and sway in the convulsions of a great war.

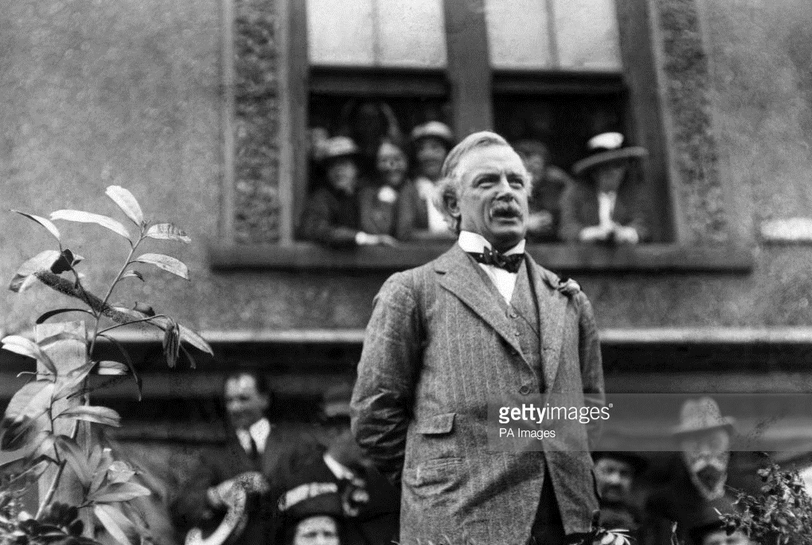

This photo is from a sufragettes rally in 1913, not speech below.

Keir Hardie: 'The Sunshine of Socialism", 21st Annioversary of formation of Independent Labour Party - 1914

11 April 1914, Bradford, England

I shall not weary you by repeating the tale of how public opinion has changed during those twenty-one years. But, as an example, I may recall the fact that in those days, and for many years thereafter, it was tenaciously upheld by the public authorities, here and elsewhere, that it was an offence against laws of nature and ruinous to the State for public authorities to provide food for starving children, or independent aid for the aged poor. Even safety regulations in mines and factories were taboo. They interfered with the ‘freedom of the individual’. As for such proposals as an eight-hour day, a minimum wage, the right to work, and municipal houses, any serious mention of such classed a man as a fool.

These cruel, heartless dogmas, backed up by quotations from Jeremy Bentham, Malthus, and Herbert Spencer, and by a bogus interpretation of Darwin’s theory of evolution, were accepted as part of the unalterable laws of nature, sacred and inviolable, and were maintained by statesmen, town councillors, ministers of the Gospel, and, strangest of all, by the bulk of Trade Union leaders. That was the political, social and religious element in which our Party saw the light. There was much bitter fighting in those days. Even municipal contests evoked the wildest passions.And if today there is a kindlier social atmosphere it is mainly because of twenty-one years’ work of the ILP.

Scientists are constantly revealing the hidden powers of nature. By the aid of the X-rays we can now see through rocks and stones; the discovery of radium has revealed a great force which is already healing disease and will one day drive machinery; Marconi, with his wireless system of telegraphy and now of telephony, enables us to speak and send messages for thousands of miles through space.

Another discoverer, through means of the same invisible medium, can blow up ships, arsenals, and forts at a distance of eight miles.

But though these powers and forces are only now being revealed, they have existed since before the foundation of the world. The scientists, by sympathetic study and laborious toil, have brought them within our ken. And so, in like manner, our Socialist propaganda is revealing hidden and hitherto undreamed of powers and forces in human nature.

Think of the thousands of men and women who, during the past twenty-one years, have toiled unceasingly for the good of the race. The results are already being seen on every hand, alike in legislation and administration. And who shall estimate or put a limit to the forces and powers which yet lie concealed in human nature?

Frozen and hemmed in by a cold, callous greed, the warming influence of Socialism is beginning to liberate them. We see it in the growing altruism of Trade Unionism. We see it, perhaps, most of all in the awakening of women. Who that has ever known woman as mother or wife has not felt the dormant powers which, under the emotions of life, or at the stern call of duty are even now momentarily revealed? And who is there who can even dimly forecast the powers that lie latent in the patient drudging woman, which a freer life would bring forth? Woman, even more than the working class, is the great unknown quantity of the race.

Already we see how their emergence into politics is affecting the prospects of men. Their agitation has produced a state of affairs in which even Radicals are afraid to give more votes to men, since they cannot do so without also enfranchising women. Henceforward we must march forward as comrades in the great struggle for human freedom.

The Independent Labour Party has pioneered progress in this country, is breaking down sex barriers and class barriers, is giving a lead to the great women’s movement as well as to the great working-class movement. We are here beginning the twenty-second year of our existence. The past twenty-one years have been years of continuous progress, but we are only at the beginning. The emancipation of the worker has still to be achieved and just as the ILP in the past has given a good, straight lead, so shall the ILP in the future, through good report and through ill, pursue the even tenor of its way, until the sunshine of Socialism and human freedom break forth upon our land.

Woodrow Wilson: 'You will say, “Is the league an absolute guaranty against war?”', the Pueblo speech, lobbying for Treaty of Versailles and League of Nations - 1919

25 September 1919, Pueblo, Colorado, USA

President Wilson attended Versailles and was desperate to have the USA ratify treaty and be part of League of Nations. It didn't happen. This was his stump speech on a tour of nation lobbying for League of Nations.

Mr. Chairman and fellow countrymen, it is with a great deal of genuine pleasure that I find myself in Pueblo, and I feel it a compliment that I should be permitted to be the first speaker in this beautiful hall. One of the advantages of this hall, as I look about, is that you are not too far away from me, because there is nothing so reassuring to men who are trying to express the public sentiment as getting into real personal contact with their fellow citizens. I have gained a renewed impression as I have crossed the continent this time of the homogeneity of this great people to whom we belong. They come from many stocks, but they are all of one kind. They come from many origins, but they are all shot through with the same principles and desire the same righteous and honest things. I have received a more inspiring impression this time of the public opinion of the United States than it was ever my privilege to receive before.

The chief pleasure of my trip has been that it has nothing to do with my personal fortunes, that it has nothing to do with my personal reputation, that it has nothing to do with anything except the great principles uttered by Americans of all sorts and of all parties which we are now trying to realize at this crisis of the affairs of the world. But there have been unpleasant impressions as well as pleasant impressions, my fellow citizens, as I have crossed the continent. I have perceived more and more that men have been busy creating an absolutely false impression of what the treaty of peace and the covenant of the league of nations contain and mean. I find, more-over, that there is an organized propaganda against the league of nations and against the treaty proceeding from exactly the same sources that the organized propaganda proceeded from which threatened this country here and there with disloyalty. And I want to say–I cannot say it too often–any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready. If I can catch any man with a hyphen in this great contest, I will know that I have caught an enemy of the Republic. My fellow citizens, it is only certain bodies of foreign sympathies, certain bodies of sympathy with foreign nations that are organized against this great document which the American representatives have brought back from Paris. Therefore, in order to clear away the mists, in order to remove the impressions, in order to check the falsehoods that have clustered around this great subject, I want to tell you a few very simple things about the treaty and the covenant.

Do not think of this treaty of peace as merely a settlement with Germany. It is that. It is a very severe settlement with Germany, but there is not anything in it that she did not earn. Indeed, she earned more than she can ever be able to pay for, and the punishment exacted of her is not a punishment greater than she can bear, and it is absolutely necessary in order that no other nation may ever plot such a thing against humanity and civilization. But the treaty is so much more than that. It is not merely a settlement with Germany; it is a readjustment of those great injustices which underlie the whole structure of European and Asiatic society. This is only the first of several treaties. They are all constructed upon the same plan. The Austrian treaty follows the same lines. The treaty with Hungary follows the same lines. The treaty with Bulgaria follows the same lines. The treaty with Turkey, when it is formulated, will follow the same lines. What are those lines? They are based upon the purpose to see that every government dealt with in this great settlement is put in the hands of the people and taken out of the hands of coteries and of sovereigns who had no right to rule over the people. It is a people’s treaty, that accomplishes by a great sweep of practical justice the liberation of men who never could have liberated themselves, and the power of the most powerful nations has been devoted not to their aggrandizement but to the liberation of people whom they could have put under their control if they had chosen to do so. Not one foot of territory is demanded by the conquerors, not one single item of submission to their authority is demanded by them. The men who sat around that table in Paris knew that the time had come when the people were no longer going to consent to live under masters, but were going to live the lives that they chose themselves, to live under such governments as they chose to erect. That is the fundamental principle of this great settlement.

And we did not stop with that. We added a great international charter for the rights of labor. Reject this treaty, impair it, and this is the consequence to the laboring men of the world, that there is no international tribunal which can bring the moral judgments of the world to bear upon the great labor questions of the day. What we need to do with regard to the labor questions of the day, my fellow countrymen, is to lift them into the light, is to lift them out of the haze and distraction of passion, of hostility, into the calm spaces where men look at things without passion. The more men you get into a great discussion the more you exclude passion. Just so soon as the calm judgment of the world is directed upon the question of justice to labor, labor is going to have a forum such as it never was supplied with before, and men everywhere are going to see that the problem of labor is nothing more nor less than the problem of the elevation of humanity. We must see that all the questions which have disturbed the world, all the questions which have eaten into the confidence of men toward their governments, all the questions which have disturbed the processes of industry, shall be brought out where men of all points of view, men of all attitudes of mind, men of all kinds of experience, may contribute their part to the settlement of the great questions which we must settle and cannot ignore.

At the front of this great treaty is put the covenant of the league of nations. It will also be at the front of the Austrian treaty and the Hungarian treaty and the Bulgarian treaty and the treaty with Turkey. Every one of them will contain the covenant of the league of nations, because you cannot work any of them without the covenant of the league of nations. Unless you get the united, concerted purpose and power of the great Governments of the world behind this settlement, it will fall down like a house of cards. There is only one power to put behind the liberation of mankind, and that is the power of mankind. It is the power of the united moral forces of the world, and in the covenant of the league of nations, the moral forces of the world are mobilized. For what purpose? Reflect, my fellow citizens, that the membership of this great league is going to include all the great fighting nations of the world, as well as the weak ones. It is not for the present going to include Germany, but for the time being Germany is not a great fighting country. All the nations that have power that can be mobilized are going to be members of this League, including the United States. And what do they unite for? They enter into a solemn promise to one another that they will never use their power against one another for aggression; that they never will impair the territorial integrity of a neighbor; that they never will interfere with the political independence of a neighbor; that they will abide by the principle that great populations are entitled to determine their own destiny and that they will not interfere with that destiny; and that no matter what differences arise amongst them they will never resort to war without first having done one or other of two things–either submitted the matter of controversy to arbitration, in which case they agree to abide by the result without question, or submitted it to the consideration of the council of the league of nations, laying before that council all the documents, all the facts, agreeing that the council can publish the documents and the facts to the whole world, agreeing that there shall be six months allowed for the mature consideration of those facts by the council, and agreeing that at the expiration of these six months, even if they are not then ready to accept the advice of the council with regard to the settlement of the dispute, they will still not go to war for another three months. In other words, they consent, no matter what happens, to submit every matter of difference between them to the judgment of mankind, and just so certainly as they do that, my fellow citizens, war will be in the far background, war will be pushed out of that foreground of terror in which it has kept the world for generation after generation, and men will know that there will be a calm time of deliberate counsel. The most dangerous thing for a bad cause is to expose it to the opinion of the world. The most certain way that you can prove that a man is mistaken is by letting all his neighbors know what he thinks, by letting all his neighbors discuss what he thinks, and if he is in the wrong, you will notice that he will stay at home, he will not walk on the street. He will be afraid of the eyes of his neighbors. He will be afraid of their judgment of his character. He will know that his cause is lost unless he can sustain it by the arguments of right and of justice. The same law that applies to individuals applies to nations.

But you say, “We have heard that we might be at a disadvantage in the league of nations.” Well, whoever told you that either was deliberately falsifying or he had not read the covenant of the league of nations. I leave him the choice. I want to give you a very simple account of the organization of the league of nations and let you judge for yourselves. It is a very simple organization. The power of the league, or rather the activities of the league, lie in two bodies. There is the council, which consists of one representative from each of the principal allied and associated powers–that is to say, the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan, along with four other representatives of the smaller powers chosen out of the general body of the membership of the league. The council is the source of every active policy of the league, and no active policy of the league can be adopted without a unanimous vote of the council. That is explicitly stated in the covenant itself. Does it not evidently follow that the league of nations can adopt no policy whatever without the consent of the United States? The affirmative vote of the representative of the United States is necessary in every case. Now, you have heard of six votes belonging to the British Empire. Those six votes are not in the council. They are in the assembly, and the interesting thing is that the assembly does not vote. I must qualify that statement a little, but essentially it is absolutely true. In every matter in which the assembly is given a voice, and there are only four or five, its vote does not count unless concurred in by the representatives of all the nations represented on the council, so that there is no validity to any vote of the assembly unless in that vote also the representative of the United States concurs. That one vote of the United States is as big as the six votes of the British Empire. I am not jealous for advantage, my fellow citizens, but I think that is a perfectly safe situation. There is no validity in a vote, either by the council or the assembly, in which we do not concur. So much for the statements about the six votes of the British Empire.

Look at it in another aspect. The assembly is the talking body. The assembly was created in order that anybody that purposed anything wrong would be subjected to the awkward circumstance that everybody could talk about it. This is the great assembly in which all the things that are likely to disturb the peace of the world or the good understanding between nations are to be exposed to the general view, and I want to ask you if you think it was unjust, unjust to the United States, that speaking parts should be assigned to the several portions of the British Empire? Do you think it unjust that there should be some spokesman in debate for that fine little stout Republic down in the Pacific, New Zealand? Do you think it unjust that Australia should be allowed to stand up and take part in the debate–Australia, from which we have learned some of the most useful progressive policies of modern time, a little nation only five million in a great continent, but counting for several times five in its activities and in its interest in liberal reform? Do you think it unjust that that little Republic down in South Africa, whose gallant resistance to being subjected to any outside authority at all we admired for so many months and whose fortunes we followed with such interest, should have a speaking part? Great Britain obliged South Africa to submit to her sovereignty, but she immediately after that felt that it was convenient and right to hand the whole self-government of that colony over to the very men whom she had beaten. The representatives of South Africa in Paris were two of the most distinguished generals of the Boer Army, two of the realest men I ever met, two men that could talk sober counsel and wise advice, along with the best statesmen in Europe. To exclude Gen. Botha and Gen. Smuts from the right to stand up in the parliament of the world and say something concerning the affairs of mankind would be absurd. And what about Canada? Is not Canada a good neighbor? I ask you. Is not Canada more likely to agree with the United States than with Great Britain? Canada has a speaking part. And then, for the first time in the history of the world, that great voiceless multitude, that throng hundreds of millions strong in India, has a voice, and I want to testily that some of the wisest and most dignified figures in the peace conference at Paris came from India, men who seemed to carry in their minds an older wisdom than the rest of us had, whose traditions ran back into so many of the unhappy fortunes of mankind that they seemed very useful counselors as to how some ray of hope and some prospect of happiness could be opened to its people. I for my part have no jealousy whatever of those five speaking parts in the assembly. Those speaking parts cannot translate themselves into five votes that can in any matter override the voice and purpose of the United States.

Let us sweep aside all this language of jealousy. Let us be big enough to know the facts and to welcome the facts, because the facts are based upon the principle that America has always fought for, namely, the equality of self-governing peoples, whether they were big or little–not counting men, but counting rights, not counting representation, but counting the purpose of that representation. When you hear an opinion quoted you do not count the number of persons who hold it; you ask, “Who said that?” You weigh opinions, you do not count them, and the beauty of all democracies is that every voice can be heard, every voice can have its effect, every voice can contribute to the general judgment that is finally arrived at. That is the object of democracy. Let us accept what America has always fought for, and accept it with pride that America showed the way and made the proposal. I do not mean that America made the proposal in this particular instance; I mean that the principle was an American principle, proposed by America.

When you come to the heart of the covenant, my fellow citizens, you will find it in article 10, and I am very much interested to know that the other things have been blown away like bubbles. There is nothing in the other contentions with regard to the league of nations, but there is something in article 10 that you ought to realize and ought to accept or reject. Article 10 is the heart of the whole matter. What is article 10? I never am certain that I can from memory give a literal repetition of its language, but I am sure that I can give an exact interpretation of its meaning. Article 10 provides that every member of the league covenants to respect and preserve the territorial integrity and existing political independence of every other member of the league as against external aggression. Not against internal disturbance. There was not a man at that table who did not admit the sacredness of the right of self-determination, the sacredness of the right of any body of people to say that they would not continue to live under the Government they were then living under, and under article 11 of the covenant, they are given a place to say whether they will live under it or not. For following article 10 is article 11, which makes it the right of any member of the league at any time to call attention to anything, anywhere, that is likely to disturb the peace of the world or the good understanding between nations upon which the peace of the world depends. I want to give you an illustration of what that would mean.

You have heard a great deal–something that was true and a great deal that was false–about that provision of the treaty which hands over to Japan the rights which Germany enjoyed in the Province of Shantung in China. In the first place, Germany did not enjoy any rights there that other nations had not already claimed. For my part, my judgment, my moral judgment, is against the whole set of concessions. They were all of them unjust to China, they ought never to have been exacted, they were all exacted by duress from a great body of thoughtful and ancient and helpless people. There never was any right in any of them. Thank God, America never asked for any, never dreamed of asking for any. But when Germany got this concession in 1898, the Government of the United States made no protest whatsoever. That was not because the Government of the United States was not in the hands of high-minded and conscientious men. It was. William McKinley was President and John Hay was Secretary of State–as safe hands to leave the honor of the United States in as any that you can cite. They made no protest because the state of international law at that time was that it was none of their business unless they could show that the interests of the United States were affected, and the only thing that they could show with regard to the interests of the United States was that Germany might close the doors of Shantung Province against the trade of the United States. They, therefore, demanded and obtained promises that we could continue to sell merchandise in Shantung. Immediately following that concession to Germany there was a concession to Russia of the same sort, of Port Arthur, and Port Arthur was handed over subsequently to Japan on the very territory of the United States. Don’t you remember that, when Russia and Japan got into war with one another the war was brought to a conclusion by a treaty written at Portsmouth, N.H., and in that treaty, without the slightest intimation from any authoritative sources in America that the Government of the United States had any objection, Port Arthur, Chinese territory, was turned over to Japan? I want you distinctly to understand that there is no thought of criticism in my mind. I am expounding to you a state of international law. Now, read articles 10 and 11. You will see that international law is revolutionized by putting morals into it. Article 10 says that no member of the league, and that includes all these nations that have done these things unjustly to China, shall impair the territorial integrity or the political independence of any other member of the league. China is going to be a member of the league. Article 11 says that any member of the League can call attention to anything that is likely to disturb the peace of the world or the good understanding between nations, and China is for the first time in the history of mankind afforded a standing before the jury of the world. I, for my part, have a profound sympathy for China, and I am proud to have taken part in an arrangement which promises the protection of the world to the rights of China. The whole atmosphere of the world is changed by a thing like that, my fellow citizens. The whole international practice of the world is revolutionized.

But, you will say, “What is the second sentence of article 10? That is what gives very disturbing thoughts.” The second sentence is that the council of the league shall advise what steps, if any, are necessary to carry out the guaranty of the first sentence, namely, that the members will respect and preserve the territorial integrity and political independence of the other members. I do not know any other meaning for the word “advise” except “advise.” The council advises, and it cannot advise without the vote of the United States. Why gentlemen should fear that the Congress of the United States would be advised to do something that it did not want to do I frankly cannot imagine, because they cannot even be advised to do anything unless their own representative has participated in the advice. It may be that that will impair somewhat the vigor of the league, but, nevertheless, the fact is so, that we are not obliged to take any advice except our own, which to any man who wants to go his own course is a very satisfactory state of affairs. Every man regards his own advice as best, and I dare say every man mixes his own advice with some thought of his own interest. Whether we use it wisely or unwisely, we can use the vote of the United States to make impossible drawing the United States into any enterprise that she does not care to be drawn into.

Yet article 10 strikes at the taproot of war. Article 10 is a statement that the very things that have always been sought in imperialistic wars are henceforth forgone by every ambitious nation in the world. I would have felt very lonely, my fellow countrymen, and I would have felt very much disturbed if, sitting at the peace table in Paris, I had supposed that I was expounding my own ideas. Whether you believe it or not, I know the relative size of my own ideas; I know how they stand related in bulk and proportion to the moral judgments of my fellow countrymen, and I proposed nothing whatever at the peace table at Paris that I had not sufficiently certain knowledge embodied the moral judgment of the citizens of the United States. I had gone over there with, so to say, explicit instructions. Don’t you remember that we laid down 14 points which should contain the principles of the settlement? They were not my points. In every one of them I was conscientiously trying to read the thought of the people of the United States, and after I uttered those points, I had every assurance given me that could be given me that they did speak the moral judgment of the United States and not my single judgment. Then, when it came to that critical period just a little less than a year ago, when it was evident that the war was coming to its critical end, all the nations engaged in the war accepted those 14 principles explicitly as the basis of the armistice and the basis of the peace. In those circumstances I crossed the ocean under bond to my own people and to the other governments with which I was dealing. The whole specification of the method of settlement was written down and accepted beforehand, and we were architects building on those specifications. It reassures me and fortifies my position to find how, before I went over men whose judgment the United States has often trusted were of exactly the same opinion that I went abroad to express. Here is something I want to read from Theodore Roosevelt:

“The one effective move for obtaining peace is by an agreement among all the great powers in which each should pledge itself not only to abide by the decisions of a common tribunal but to back its decisions by force. The great civilized nations should combine by solemn agreement in a great world league for the peace of righteousness; a court should be established. A changed and amplified Hague court would meet the requirements, composed of representatives from each nation, whose representatives are sworn to act as judges in each case and not in a representative capacity.” Now, there is article 10. He goes on and says this: “The nations should agree on certain rights that should not be questioned, such as territorial integrity, their right to deal with their domestic affairs, and with such matters as whom they should admit to citizenship. All such guarantee each of their number in possession of these rights.”